Contact tracing apps: A new world for data privacy

Global | 出版物 | February 2021

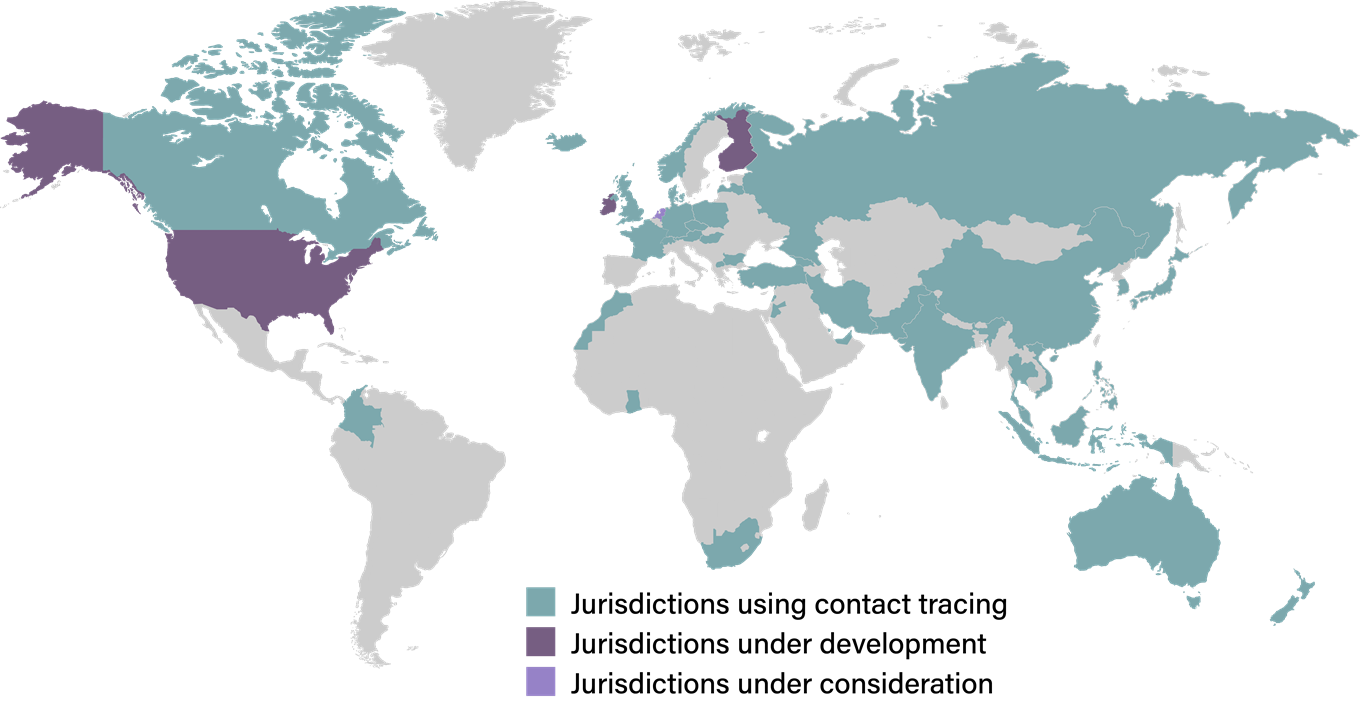

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen governments across the world restricting civil liberties and movement to new levels. To aid the safe lifting of current public health restrictions, new technologies are being developed – contact tracing apps - and rolled out to automate labour intensive tasks critical to containing the spread of the virus. Our contact tracing survey summarises the principal regulatory and policy issues applicable to contact tracing across a range of key jurisdictions in real time.

Contact tracing global snapshot

Australia Canada China France Germany Hong Kong Italy Indonesia PolandRussia South Africa Thailand The Netherlands Turkey United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States

Australia

As at December 1, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

The Australian Federal Government launched a contact tracing app (the COVIDSafe App) on April 26, 2020. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app in your jurisdiction (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

By the Australian Government

By private sector organisations

|

Canada

As at July 1, 2020

China

As at May 11, 2020

France

As at December 2, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

The app, StopCovid, developed by INRIA (National Institute for Research in Digital Science and Technology) was made public on June 2, 2020. A decree (Decree No. 2020-650 of May 29, 2020 relating to data processing known as “StopCovid”) was published on May 29, 2020, setting the definitive legal framework for the implementation of the app. The Government presented a new version of the app named “TousAntiCovid” on October 22, 2020. The Health Ministry stated that TousAntiCovid is an update of the latest version of StopCovid. As part of the new features, TousAntiCovid provides easy access to other tools including “DepistageCovid”, which provides a map of nearby testing centres and waiting times, and “MesConseilsCovid”, which provides personalised advice on how to protect oneself and others. Since its launch, the app has been downloaded by almost 9.5 million people and more than 13,000 people have been notified as having been in contact with an infected person. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app in your jurisdiction (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

Two weeks after the app launched, Gaëtan Leurent, a French researcher in cryptography, explained that the app collects more data than originally understood. His findings show that all cross-contacts are sent to the central server, contrary to the government guidance which states that only the app users who had been in contact for 15 minutes, closer than one meter away from a person who tested positive for COVID-19 would be stored, meaning that the app processes more data than necessary to trace the spread of the virus, and is not compliant with the data minimization principle. The French Government has not denied the comments. The second version of StopCovid, launched at the end of June, remedied this problem, but the French Data Protection Authority (the “CNIL”) noted that this second version still contained certain shortcomings concerning user information, the subcontracting contract granted to INRIA and certain data processing aimed at securing the app. Therefore, the CNIL gave the Health Ministry formal notice to remedy this on July 20, 2020. Following the formal notice, as the CNIL considered the processing implemented were now compliant with the EU and French legislative data protection requirements, it declared the closure of the formal notice on September 3, 2020. The main concern relates to the use of a centralized server, which increases the risk of possible cyber-attacks and the temptation to exploit this data for purposes other than those provided for by law.

|

Germany

As at June 23, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

The German Federal Government has launched an official App "Corona-Warn-App" on June 16, 2020 which was developed by SAP and Telekom on behalf of the German Federal Government. The "Corona-Warn-App" is based on the Privacy-Preserving Contact Tracing (“PEPP-IT”). The Corona-Warn-App and backend infrastructure will be entirely open source - licensed under the Apache 2.0 license. The Corona-Warn-App is being developed on basis of the Exposure Notification Framework (“ENF”) provided by Apple and Google, which will uses Bluetooth Low Energy technology (“BLE”). The Corona-Warn-App will collect pseudonymous data from nearby mobile phones using BLE. As soon as two users approach each other within a distance of about two meters and remain at this distance for fifteen minutes or longer, their apps will exchange data via BLE. If an user tests positive for COVID-19, the user can feed the test result into his/her Corona-Warn-App. The Corona-Warn-App will then anonymously inform all stored contacts. The data will be stored locally on each device preventing access and control over data by authorities or a third party.

Currently there is one other app available in Germany launched by Robert Koch Institute (German federal government agency and research institute responsible for disease control and prevention, “RKI”) – “Datenspende-App”. This app does not yet trace contacts, but only general movement and fitness information. The app collects the user data using their fitness tracker and sends it to the RKI. The RKI analysis anomalies in the data, which is sorted by postcode: As pulse rate, sleep rhythm and activity level change due to an acute respiratory disease, the RKI claims that it can also indicate a Covid-19 disease having this data. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app in your jurisdiction (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

“Corona-Warn-App”: - There are no major privacy concerns as the Corona-Warn-App has been designed with a special focus on privacy from the beginning. The German Data Protection Authorities generally support the Corona-Warn-App and only expressed minor concerns, but less on the Corona-Warn-App itself but rather on the way it may be used:

The Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (Bundesbeauftragter für den Datenschutz und die Informationsfreiheit) announced that the use of the telephone-Tan-registration is not an optimal solution because the complete anonymity of the user will no longer be guaranteed. “Datenspende-App”: There are several concerns indicated by Chaos Computer Club, a cyber security NGO, in particular:

|

Hong Kong

As at February 26, 2021

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

|

Is technology being used by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

Quarantine monitoring – mandatory wristbands have been introduced for those arriving from overseas and are required to be worn for a 14 day home quarantine period. The wristband is linked to an app, StayHomeSafe. Contact tracing - on November 16, 2020, the Hong Kong Government launched a voluntary contact tracing app, LeaveHomeSafe. The app allows users to record the date and time they visited different venues by scanning the venue QR code at participating venues to log their arrival and clicking the “Leave” button in the app to mark their departure. If a confirmed case is later discovered at a participating venue, the app will notify users who have visited the same venue at a similar time to the confirmed case together with health advice. The app also allows users who are infected with COVID-19 to voluntarily upload the encrypted visit records to the Centre for Health Protection (CHP) for epidemiological investigations. |

|

What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app in your jurisdiction (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

StayHomeSafe: The key privacy concerns are excessive data collection and that data may be used for other purposes such as tracking. The Hong Kong Government addressed this concern by using geo-fencing technology rather than GPS location tracking. Other privacy concerns include storage and access to the data, as the privacy policy of the app does not contain clear information regarding retention of and access to such data. LeaveHomeSafe: There are similar privacy concerns as with the StayHomeSafe app. However, according to the Hong Kong Government, LeaveHomeSafe does not use positioning services or any other data on the users’ mobile phones and the data is encrypted and stored only in users’ mobile phones. |

Italy

As at June 19, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used or developed by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

The Government has selected a contact-tracing app developed by a well-known software house. On 29 April the Italian Government issued a law decree setting out inter alia the rules governing the adoption of such app (Law Decree no. 28 of 30 April 2020, the Decree). After a beta test in four regions, the app has been made available in the whole of Italy since June 15. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

The Data Privacy Authority considers that the Decree on the app complies with its previous comments on this topic and with EDPB guidelines. Main privacy concerns lie in data minimization, data security, re-identification risk and actual prevention of use of such data for other purposes. The Decree addresses a wide-spread concern about ownership and localization, providing that the data controller shall be the Ministry of Health, and that data shall be stored in servers on the Italian territory. Private sector apps to be used in the workplace need to comply with strict Italian rules on remote monitoring of employees, as well. |

Indonesia

As at May 11, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used or developed by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

The Ministry of Information and Communication (MOCI) launched a mobile application called PeduliLindungi. The app enables users to compile data related to the spread of COVID-19 in their communities to help bolster the Indonesian Government’s efforts to trace and track confirmed cases. Users are expected to register as participants and share their locations when travelling and also trace whether they have had contact with persons exposed to COVID-19. The app will also alert users entering crowds or COVID-19 red zones, namely locations where there are confirmed COVID-19 cases. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

That said, the Government has not been very transparent on what measures or methods it is using to ensure protection of data privacy. For instance, the app mentions that it will have periodic updates to improve security and privacy. Whilst the private sector has conveyed privacy concerns, there has not been any major privacy incidents reported thus far. |

Poland

As of February 2, 2021

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

The Polish Government has launched two apps (“Kwarantanna domowa” app and “STOP COVID - ProteGO Safe” app). The “Kwarantanna domowa” application is intended for people who are subject to 10-day mandatory house quarantine due to suspected COVID-19 exposure. The application uses geolocation and face recognition technology to ensure that relevant people are quarantined. The “STOP COVID - ProteGO Safe” application is designed to allow users to monitor their level of risk of getting infected. The app facilitates self-assessment of the risk of COVID-19 infection and, if the user decides to do so, it allows the user to scan the environment for other smartphones on which the application is installed and saves the history of anonymous identifiers encountered. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app in your jurisdiction (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

“Kwarantanna domowa” – due to concerns that the use of the “Kwarantanna domowa” application may violate users’ rights to personal data protection, the Polish Ombudsman has asked the President of the Office for Personal Data Protection and the Prime Minister for an opinion on this matter. According to the authorities, appropriate encryption methods have been used and the data processing model complies with the requirements set out in the GDPR. “STOP COVID - ProteGO Safe” – despite initial numerous reservations, the application is currently considered secure, providing complete anonymity and data encryption. Moreover, it is based on Exposure Notification technology developed by Google and Apple. |

Russia

As at May 15, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used or developed by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

There is no single technology that has been introduced consistently throughout Russia. However, monitoring of the spread of COVID-19 is done at the local level and some technologies have been introduced in certain regions of Russia. Moscow, where the number of cases is highest (about 50% of the total cases), is the only region of Russia that has introduced a technology for monitoring the location of citizens (as well as their close contacts) with confirmed COVID-19 via an app called Social Monitoring. The Social Monitoring App was developed by the Department of Information Technologies for the city of Moscow. The app is intended for monitoring violations of a self-isolation regime and quarantine established for those who are being treated at home and/or are limited in leaving their places of residence. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

There are significant privacy concerns regarding the implementation of a Social Monitoring App. In addition to those mentioned above they include the following:

|

South Africa

As at May 11, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used or developed by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

The South African government has partnered with the University of Cape Town to develop a smartphone app to assist government with tracking people who may be unaware that they have COVID-19 and to track people who have come into contact with others who are COVID-19 positive. The App is called Covi-ID. The South African Government acknowledged that it is critical that the Government works collaboratively with South African technology companies and individuals to leverage technology capabilities in the fight against COVID-19 and its effects. We are aware that the Government has approached technology companies to identify suitable projects that may assist the Government with its response to the crisis, in particular, its plan to develop a national COVID-19 Tracing Database. The database seeks to track people who are known or suspected to have come into contact with persons known or suspected to have COVID-19. On 2 May 2020, the Department of Health also launched a Whatsapp based symptom reporting process. The details of the back end and privacy controls are unknown at this stage. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

Given that South African privacy laws are not yet in force, there is a concern that personal information may not be properly protected during the pandemic and may be used for further processing not anticipated on collection of the data. On the WhatsApp symptom tracker it is unclear who is processing the information submitted and where else it may be disclosed. There are no terms and conditions available regarding the use of this functionality. Even though South African privacy laws are not in place, there is a constitutional right of privacy; however this may be infringed where there are larger public interest considerations that outweigh the impact on privacy. The Covi-ID App has a GDPR-based privacy policy and also voluntarily submits to the South African data privacy laws not yet in place. |

Thailand

As at May 11, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used or developed by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

The technologies being used in Thailand for tracking COVID-19 are mostly contact tracing applications used together with the cell phone location data of the user. The Thai Government authorities (e.g. Department of Disease Control (DDC), Office of The National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) etc.) are currently using these applications to monitor and track individuals who have been infected or classified as being in a “high risk cluster” (including the individuals who may have been infected) with support from the private entities and state enterprise (e.g. Airport of Thailand (AOT), mobile service providers and digital start-ups). The apps in use are:

|

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

Excessive data collection which may be used for other purposes such as tracking individual after the spreading of COVID-19 has ended. |

The Netherlands

As at December 18, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used or developed by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

The Government launched a contact tracing app, CoronaMelder, on October 10, 2020. The accompanying Act, the Temporary Act Notification-application Covid-19 (Tijdelijke wet notificatieapplicatie covid-19) (the Temporary Act) was passed by the Dutch Parliament on October 6, 2020. The Dutch Data Protection Authority (the DDPA) advised the Dutch Government on CoronaMelder on August 6, 2020. Furthermore, the Government had published a draft bill which amends the Dutch Telecommunication Act (Telecommunicatiewet) and allows the National Institute for Health and Environment (Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu) (RIVM) to access telecommunication data (the aggregated location and traffic data of citizens) through the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek) for the purpose of controlling the spread of COVID-19, the Temporary Act Information Provision RIVM regarding Cocid-19 (Tijdelijke wet informatieverstrekking RIVM i.v.m. COVID-19). The DDPA had reviewed the initial version of the draft bill and identified a number of areas that required improvement: (i) given that the bill was drafted with great urgency, its scope should be limited to the COVID-19 crisis alone (it allowed RIVM to access data for future epidemics as well); (ii) the purpose and necessity of the extended powers of the RIVM needed to be stated clearly; and (iii) no maximum retention period for the telecommunication data was included. The Government had considered the comments from the DDPA and published the draft bill on May 29, 2020, as well as a revised draft bill on June 24, 2020. The DDPA had subsequently commented in the media that it does not agree with the draft bill. According to the DDPA, the data is not unconditionally anonymised, the purpose and necessity of the bill need to be stated more clearly and the safeguards proposed by the DDPA need to be implemented into the new draft bill more sufficiently. On October 2, 2020, another revised draft bill was published by the Government. The State Secretary of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy (Staatssecretaris van Economische Zaken en Klimaat) also published an accompanying letter. In the letter, the State Secretary confirms that, due to the anonymization of the data, no personal data will be processed as a result of the draft bill. Furthermore, according to the State Secretary, the safeguards proposed by the DDPA in respect of the initial draft bill have been implemented, where feasible. Finally, the State Secretary reiterates the purpose and necessity of the draft bill. The DDPA has not yet responded to the letter or the revised draft bill. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

According to the legislative history of the Temporary Act, one of the major concerns from the Parliament, the DDPA, the Netherlands Institute for Human Rights (College voor de rechten van de mens) and others was that the use of the app would be made compulsory by third parties. The Temporary Act therefore contains a so-called “anti-abuse” clause, which prohibits anyone from requiring the others to use CoronaMelder, or any other similar digital resource.

In addition, it was previously indicated by stakeholders that it is important to make clear which (governmental) organisations will use the app and who the data controller is in respect of the personal data. This is important as the data controller is responsible for complying with the GDPR and is the point of contact for data subjects in order to receive information on the data processing and to enforce their data subject rights under the GDPR. According to the Temporary Act, the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport is the joint controller, together with the Regional Public Health Authorities (the local GGD).

Since CoronaMelder was launched, critics have expressed that, although the app makes use of anonymized codes, in certain cases the identity of an infected user can still be unravelled. To illustrate this, a website has been launched on which visitors can see who uses CoronaMelder and can subsequently attribute a name to such users on the website. The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy acknowledges that the risk of identification exists, but it has also stressed that the privacy risks seem to be limited, as identification would require significant efforts.

|

Turkey

As of January 21, 2021

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

In collaboration with the Information Technologies and Communication Authority and all mobile phone operators, the Turkish Ministry of Health has launched a mobile contact tracing app called “Hayat Eve Sığar” (Life Fits Into Home) to monitor the movement of diagnosed COVID-19 patients and to warn users if they enter a high COVID-19 risk zone or if they had crossed paths with a diagnosed patient. Diagnosed COVID-19 patients are warned via text messages and automated calls in the event that they leave their place of isolation. A recently added feature to the app now allows users to scan barcodes at selected venues (e.g. participating shops, stores, etc.) to review detailed information such as the number of people who have recently visited that location. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app in your jurisdiction (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

The app is not being used by private sector organisations and to the best of our knowledge, there have been no surveys or polls to test public opinion on the app or any privacy concerns around it. However the major privacy concerns in relation to an app of this type would be the risk of a cyber attack and exfiltration of personal data (including sensitive health data) and whether established data processing principles would be duly complied with, including purpose limitation and time limitation. |

United Arab Emirates

As at June 17, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

So far the UAE has developed three COVID-19 tracing apps. The Abu Dhabi Department of Health first launched StayHome, which was then followed by TraceCovid. The UAE has now recently launched a new tracing app, ALHOSN. All three apps are designed to identify people who have been in close contact with infected individuals, allowing authorities to immediately reach out to possibly infected individuals and provide them with the necessary healthcare treatments. From the information publicly available, ALHOSN was jointly launched by the Ministry of Health and Prevention, Abu Dhabi Health Authority and Dubai Health Authority to serve as the official digital tracing app for COVID 19. The new app combines the features of the two previous apps, StayHome and TraceCovid. The new app also provides additional features such as access to user test results, and a health colour coding system that identifies the status of the users’ health. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app in your jurisdiction (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? | There is no Federal data privacy regulator or regulations/laws in the UAE so no comments from any such authority exist. The Government has not provided too much information on what measures and actions it is using to ensure data privacy. The Department of Health Abu Dhabi only said that privacy of personal information will be protected - there is therefore a concern that personal data collected may not be properly protected during the pandemic and may be used for further processing that was not anticipated. |

United Kingdom

As at October 05, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used or developed by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

Yes. The National Health Service (NHS), has rolled-out a contact-tracing smartphone app for people living in England and Wales, aged 16 or over. It is based on decentralised “exposure notification” and “exposure logging” technology developed by Apple and Google. The app can instruct users to self-isolate if it detects that they were nearby an individual with the virus; it can alert to the level of coronavirus risk in users’ postcode districts; it includes a check-in scanner to alert users if a venue visited has been categorised as an outbreak hotspot; and it allows users to order a coronavirus test. Different apps are in use in Scotland and Northern Ireland. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

Concerns centre on privacy principles of security, data minimisation, transparency and accountability and these apply both to private and Government use of tracing apps. In particular in relation to Government use:

In particular in relation to private sector use:

|

United States

As at June 5, 2020

| Key points | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Is technology being used or developed by the government to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. contact tracing app, CCTV, cell phone location data, credit-card history)? |

In the U.S., there has been some minimal, state-level efforts in this area, and two federal bills introduced in Congress. There also continues to be a major collaboration between Apple and Google. The two federal bills focus on COVID-19 data privacy and create new rights for individuals related to COVID-19 health information. Some key similarities include requiring covered entities to: (1) obtain “affirmative express consent” before collecting and using COVID-19 related health information (subject to a few expectations); (2) disclose their data practices related to COVID-19 health information; and (3) create and implement reasonable data security and privacy safeguards. Some key differences include: (i) the definition of covered information, with one bill going beyond COVID-19 health information and including any physical or mental health status; and (ii) the coverage of employee-related data, with one bill essentially exempting COVID-19 related health information used to determine eligibility for entering the workplace facility (e.g., temperature checks). Apple and Google released an API in mid-May that can be used in official publich health apps in the iOS and Google Play stores. The API uses detection of Bluetooth signals in order to track location of users over time. For example, if User A has been in close contact with User B, who later self-identifies as having COVID-19 within a pre-identifined time window, then User A will be alerted if the potential exposure. |

| What are considered to be the major privacy concerns in relation to the app (in relation to its use (a) by the government; and (b) by private sector organisations)? |

The major privacy concerns that would normally be associated with this type of data collection appears, on paper, to have been mitigated through: (i) affirmative express consent (in the case of the federal bills) and (ii) the use of a complex public key cryptography infrastructure develop by Apple and Google for the API. The devil of course, is always in the detail, and so we will be able to better judge when apps using this API go live. At this point, notwithstanding a fair amount of noise in the media about privacy concerns, this approach could work well, if affirmative express consent is obtained (and the bills ultimately become law) and the crypto implementation by Apple and Google is sound. |

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .