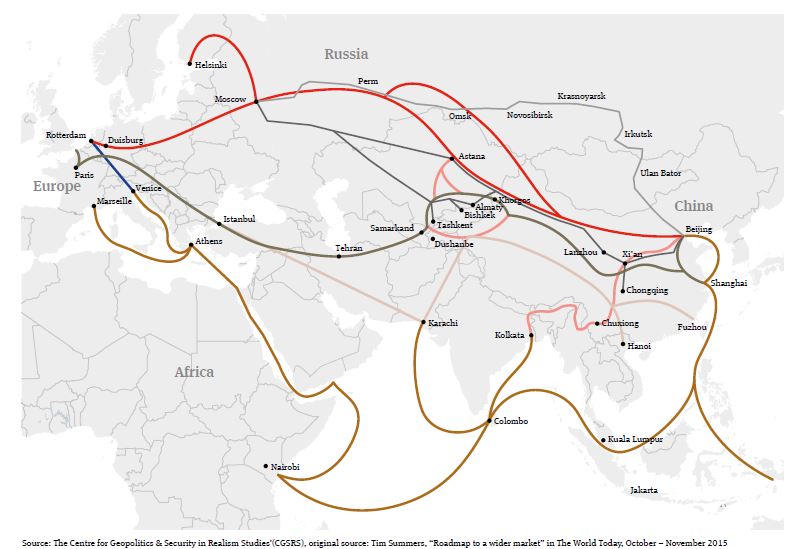

Although the Belt & Road Initiative brings many opportunities for investors, there are still many challenges and risks. Differing economic and political situations of B&R countries means there are inherent risks, ranging from political instability and security concerns, to legal, regulatory and funding challenges. Potential investors will need to conduct detailed due diligence and understand project and financing structures as well as the legal and regulatory regimes of the countries along the B&R routes.

Geographically, some of the terrain is harsh, involving long distances, high costs and potential security and insurance concerns.

Some of the regions covered by B&R are plagued by territorial disputes and local wars, endangering the implementation of the Initiative. Religious extremism may jeopardise the safety of projects. Local corruption, tensions with neighbours and domestic issues may also hinder projects. Political risk guarantees may help, but these may not be available for all jurisdictions and projects, particularly those going across several borders.

Other examples of political instability were seen during the construction of the controversial Myitsone Hydropower Project in Myanmar, which was suspended due to NGO opposition in 2011.12 Likewise, the Sino-Thai railway project – featuring 873km dual tracks – has been protested against by Thai citizens.13 Works on the US$1.4 billion offshore Colombo Port City project being constructed by CCCC, which was suspended by the Sri Lankan government in March 2015, have only recently been resumed.14 The project was initially suspended because of regulatory and environmental concerns, and a perceived scope for lack of transparency.

Other countries have generally been supportive of the Belt & Road Initiative, recognising the scope for co-investment and cooperation, but some are wary of China’s potential ambitions locally and on the world stage.

From a financing perspective, low host country credit ratings may present a challenge. Co-financing sources would also be wider if the US and Japan agreed to join the AIIB as members, but the funding gap in Asia and other B&R countries will not be met by AIIB funding alone. For the B&R Initiative to be successful and sustainable, China will need to engage the private sector and the commercial banks.

Some B&R countries are likely to present regulatory challenges in project approvals and implementation, particularly at a local level. Traditionally, infrastructure projects require high-standard management, have long operating cycles and uncertain profits. Therefore, it is vital that investors have a clear understanding of the relevant legal systems, security structures and risk management profiles. Regulatory reform will also be needed both in China and to open up markets in B&R countries, including in the areas of financial integration, customs clearance, antibribery and foreign investment.

When it comes to identifying enforcement risks, foreign investors tend to over-emphasise enforcement risks when dealing with a Chinese EPC contractor. Chinese parent company guarantees will invariably be with a mainland Chinese state owned enterprise, probably based in Beijing. This means a Singapore, London or Hong Kong arbitration award may ultimately need to be enforced in courts in Beijing. China has introduced procedures to ensure that such awards are readily enforced in China, and in practice, this should usually be the case. However, occasionally sponsors have encountered issues calling bank guarantees from Chinese banks. Chinese law allows a PRC court to claim jurisdiction to restrain a call on the bank guarantee where there is any claim of fraud. This risk should not be overstated, but sponsors should still consider asking for bank guarantees issued by a non-Chinese bank.

More generally, the current world economy remains unstable and investment appetite uncertain.