Publication

Generative AI: A global guide to key IP considerations

Artificial intelligence (AI) raises many intellectual property (IP) issues.

United Kingdom | Publication | 五月 2020

This article was first published in the April edition of the Journal of International Banking and Financial Law.

DAC 6 is a new EU reporting regime targeted at tax-motivated arrangements but framed much more widely. From July of this year, intermediaries and taxpayers will need to report cross-border arrangements which bear one or more of a series of prescribed hallmarks. This includes any transaction entered into since June 25, 2018. Finance parties may well be within the scope of the regime and thus have an obligation to report. Steps should be taken to identify historic transactions that need to be reported and to put processes in place to identify in scope transactions going forward.

Transparency is high on the global agenda for governments looking to counter tax avoidance. Attention has shifted from tax-motivated transactions to ordinary transactions which may have a tax effect, even where not driven by tax planning motives. One result of this in the EU is Council Directive 2018/822 EU (amending Directive 2011/16/EU); commonly known as “DAC 6”.

DAC 6 requires mandatory reporting of cross-border arrangements when they involve at least one EU member state and bear one or more of a number of “hallmarks”. The UK is to implement the regime regardless of Brexit.

The potential breadth of the arrangements picked up by the Directive and the fact that it is not limited to taxmotivated transactions means that it presents a considerable compliance challenge for those within its scope.

The obligation to report under DAC 6 primarily falls on “intermediaries”. An intermediary is any person who:

In the UK the former are referred to as “promoters” with the latter referred to as “service providers”.

The broad scope of the definition means that a large number of those involved are potentially “intermediaries”. Those caught include consultants, accountants, financial advisers, lawyers (including in-house counsel), banks, trust companies, insurance intermediaries, holding companies and group treasury functions.

Looking at finance parties, “promoters” would seem likely to include the corporate finance advisor on an M&A deal, the sponsor on a listed transaction or any bank involved in marketing or arranging any structured arrangements. “Service providers” is much wider and could cover a bank whose only involvement with a transaction is the provision of third-party financing.

A single transaction may therefore involve many intermediaries. Take for example a leveraged M&A transaction where the intermediaries involved would include the investment bank co-ordinating the deal, lawyers, accountants, corporate services companies, holding and group treasury companies, as well as the lenders involved in any acquisition financing as “service provider” intermediaries.

There is a difference in how “promoters” and “service providers” are treated under DAC 6 as “service providers” will not be considered to be intermediaries if they did not know, and could not reasonably have been expected to know, that they were involved in a reportable arrangement. The UK in its guidance to date states that a lending bank would not be expected to make a disclosure if it does not have sufficient knowledge of the wider arrangements and, crucially, of whether any hallmark is triggered. However, in practice, a lending bank may not be able to prove its lack of knowledge especially if structure papers or tax reports are part of its credit appraisal process.

In determining whether a service provider could “reasonably be expected to know” a hallmark applies, service providers are not expected to have performed additional due diligence beyond what is normal, taking into account the regulatory landscape, for the client in question. A bank that takes steps to remain wilfully ignorant by intentionally avoiding asking questions about the underlying transaction may well still meet the knowledge test by virtue of this limb.

A lender may then find out that their financing into a structure is going to be used to make a payment to an associated company, for example, in the Cayman Islands or Panama. These jurisdictions were added to the EU blacklist on 18February 2020 and so if the payments are deductible then the arrangement would be reportable under hallmark “C” (assuming for these purposes they remain on the blacklist at the time of the example arrangement). The lending bank may have knowledge of this as part of its due diligence but even if it does not, to argue that there is no reporting obligation for the lending bank would require reliance on not reasonably being expected to know that the hallmark was met – not necessarily a comfortable position to be in.

There is no equivalent knowledge defence for “promoters” so, for those financial entities who are actively involved in putting together a transaction, it is assumed that they will have an understanding of how the transaction works and what its effect will be. Taking the example of deductible payments to blacklisted jurisdictions, an investment bank organising a deal would be assumed for the purposes of DAC 6 to know the tax consequences of the arrangement, ie that the payments are deductible, even if they did not have actual knowledge of that fact.

Practically though for both investment banks co-ordinating a deal and a lender at the fringes of a transaction the implications of DAC 6 are similar in that they could both have reporting obligations. Accordingly, they will both need to ensure that the intermediaries involved in a transaction are clear on who will be reporting and what they will be reporting as helpfully DAC 6 only requires the relevant information to be reported once.

It is also worth flagging that implementation of the ‘intermediaries’ concept is not aligned in all jurisdictions. The German implementing law, for example, does not extend the definition of “intermediaries” to those who would come under the UK’s “service providers” definition. This means that a number of roles carried out by banks assisting with reportable transactions may effectively be excluded from the reporting obligation. Consideration should be given as to whether and how this should be reflected in any transaction documentation.

Arrangements are only notifiable if they possess a specified hallmark. Certain of these hallmarks are subject to a requirement that the main benefit or one of the main benefits expected from the arrangement is a tax advantage (the “main benefit test”). There is no de minimis value for the arrangements or level of tax benefit in order for arrangements to be reportable.

The details of the hallmarks are quite detailed, but Table 1 overleaf provides a summary and sets out those which the main benefit test applies to.

One of the key difficulties facing intermediaries is in applying these “hallmarks”. In particular for “promoters” there is concern around the level of tax knowledge that is required to determine whether a hallmark applies. Will an investment banker, even an extremely well-informed one, know whether payments are within a unilateral transfer pricing safeharbour (hallmark “E”) or involve deductions in multiple jurisdictions (hallmark “E”) particularly given that there is no “main benefit test” qualifier for these. This, though, is knowledge that will be assumed for “promoters” in determining whether they need to report.

A further concern is on the interpretation of the hallmarks. Hallmark “A”, for example, refers to standardised documentation or structures but there is a question over what constitutes “standardised” – if a particular structure is commonly used for certain transactions would this be enough for it to be considered “standardised”? The UK guidance suggests that this would not be the case but other jurisdictions may take a different approach. Similar concerns arise with respect to the other hallmarks and while the hope is that through guidance a sensible and conformed approach will be taken by EU tax authorities this cannot be guaranteed.

An arrangement will be reportable where it concerns either more than one EU member state or a member state and a third country and, in each case, one of a number of other criteria are met. These criteria include, for example:

The UK has taken the view that for an arrangement to “concern” a jurisdiction, it must be of some material relevance to the jurisdiction: a branch contracting with entities in the jurisdiction where it is located will not be entering into a cross-border arrangement merely by virtue of its head office jurisdiction. There is no bright line test: whether an arrangement meets the test will be a question of fact and degree.

Where an intermediary has connections with more than one EU member state, DAC 6 sets out a hierarchy to determine where disclosure should be made. This is determined, in descending order, by:

Applying this hierarchy can give rise to surprising results. Taking the example of a UK branch of a French bank – the UK branch is likely to need to report transactions arranged in the UK in the jurisdiction of residence of the bank as a whole – so France. If, though, the French implementation of DAC 6 means that the transaction is not reportable there, the bank may need to revert to consider the position in the UK. Even if the arrangement is reportable in France, the bank may still need to consider whether the information requirements of France and the UK are aligned so that a report made in France effectively franks the UK obligations.

Where multiple intermediaries are involved intermediaries will be exempt from the obligation to file a report if they have evidence that the information has already been provided by another party.

Where finance parties are involved in transactions which may be reportable then they should ensure that it is clear as to who will report and what they will report and this should be agreed at an early stage in the transaction.

Whilst there is no prescribed hierarchy as to which intermediary should make disclosure there is some logic to it being the intermediary who is most closely involved in the transaction, thereby effectively franking the reporting obligation of the other intermediaries. For finance parties which are “service providers” it therefore makes sense to ensure that the “promoter” intermediaries in the transaction are aware of the need to analyse whether or not the transaction is reportable and to file the necessary report.

An important point to note is that if there are no “intermediaries”, or those intermediaries are prevented from reporting (for example, because the information is covered by legal privilege), the obligation to report falls on the taxpayer. This could be relevant where a transaction is being arranged by a bank as taxpayer without the involvement of other intermediaries.

| Categories | Hallmarks | Main benefit test? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category A

Commercial characteristics seen in marketed tax avoidance schemes |

Taxpayer or participant under a confidentiality condition in respect of how the arrangements secure a tax advantage. |

✓ |

|

| Intermediary paid by reference to the amount of tax saved or whether the scheme is effective. |

✓ |

||

| Standardised documentation and/or structure. |

✓ |

||

| Category B Tax structured arrangements seen in avoidance planning |

Loss-buying. |

✓ |

|

| Converting income into capital. |

✓ |

||

| Circular transactions resulting in the round-tripping of funds with no other primary commercial function. |

✓ |

||

| Category C Cross-border payments, transfers broadly drafted to capture innovative planning but which may pick up many ordinary commercial transactions where there is no main tax benefit. |

Deductible cross-border payment between associated persons … |

||

| to a recipient not resident for tax purposes in any jurisdiction | |||

| to a recipient resident in a 0% or near 0% tax jurisdiction. |

✓ |

||

| to a recipient resident in a blacklisted country |

|||

| the payment is tax exempt in the recipient’s jurisdiction |

✓ |

||

| the payment benefits from a preferential tax regime in the recipient jurisdiction. |

✓ |

||

| Double tax relief claimed in more than one jurisdiction in respect of the same income. |

|||

| Asset transfer where amount treated as payable materially different between jurisdictions. |

|||

| Category D

Arrangements which undermine tax reporting under the Common Reporting Standard (CRS)/ transparency. |

Arrangements which have the effect of undermining reporting requirements under agreements for the automatic exchange of information. |

||

| Arrangements which obscure beneficial ownership and involve the use of offshore entities and structures with no real substance. |

|||

| Category E Transfer pricing: non-arm’s length or highly uncertain pricing or base erosive transfers. |

Arrangements involving the use of unilateral transfer pricing safe harbour rules. |

||

| Transfers of hard to value intangibles for which no reliable comparables exist where financial projections or assumptions used in valuation are highly uncertain. |

|||

| Cross-border transfer of functions/risks/assets projected to result in a more than 50% decrease in EBIT during the next three-years. |

|||

The information to be reported is a long and detailed list including details of all intermediaries involved and taxpayers potentially affected; the applicable hallmark(s); a summary of the arrangement, its value and details of relevant local laws. The information reported will then be contributed to a central directory accessible by member states.

Intermediaries may not be able to disclose all information that they may have.

DAC 6 is clear that member states can provide exceptions to the obligation to report where it would breach legal professional privilege under domestic law. Where that is the case, DAC 6 requires intermediaries to notify any other intermediaries or the relevant taxpayer of their reporting obligation.

EU member states were required to implement DAC 6 into national legislation by 31 December 2019 with effect from 1 July 2020. That this was a challenging timeframe was borne out by the fact that infringement action is now being taken against 15 jurisdictions (including the UK, France and Spain) for failure to implement the regime in time.

From 1 July 2020, reports will need to be filed within 30 days of the earlier of the day on which the arrangement is made available or ready for implementation and the day on which the first step in implementation is made.

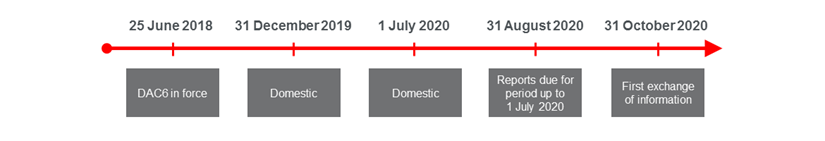

The Directive also requires reporting of arrangements dating back to 25 June 2018 (being the date DAC 6 was adopted by the European Council). Reports for arrangements entered into between 25 June 2018 and 1 July 2020 must be made by 31 August 2020. This timetable is set out in Diagram 1 above.

Where the reportable arrangement is a “marketed arrangement” (marketed tax schemes which can be implemented with minimal customisation), there are ongoing quarterly reporting obligations. In other cases, there may also be ongoing annual reporting obligations: the UK regulations require annual reporting by taxpayers as long as the identified tax advantage of the arrangement is continuing.

Member states are obliged to impose “effective, proportionate and dissuasive” penalties as part of their implementation of DAC 6. The UK position is that there will be a £5,000 penalty per breach with daily penalties of up to £600 per day charged where reporting failures are serious: for example, where there is a repeated or intentional failure to report. France has proposed penalties of up to €10,000 per reporting failure, while Germany has penalties of up to €25,000 and Luxembourg’s draft legislation provides for penalties of up to €250,000.

Finance parties should look back to arrangements undertaken as principal or in which they have been involved from 25 June 2018 to see whether any reporting obligations arise and, if so, how these obligations will be met.

Going forward, it will be necessary to ensure that procedures are in place to identify reportable arrangements and collect the necessary information to enable reporting. It would seem sensible for banks to ensure that there is agreement at the outset of any transaction with multiple intermediaries as to which intermediary will make any necessary report. This is likely to be the intermediary most closely involved with facilitating the arrangement and so in some instances (for example, on listed transactions, M&A or structured arrangements) could well be the co-ordinating bank.

Given that there may be different reporting obligations across jurisdictions it would also be prudent for finance parties who are reliant on others reporting to input into the scope and content of any report to ensure that it franks their DAC 6 obligations.

Where it is the bank that is required to make the report, it will be necessary to ensure that they have the necessary permissions from taxpayers to disclose reportable arrangements and that they are not reporting privileged information.

The UK has indicated that penalties will not be imposed where the entity has “reasonable procedures” in place to ensure compliance (Germany has also indicated that robust internal procedures will be an important factor and other jurisdictions are expected to adopt a similar approach). Reasonable procedures are likely to require training of in-house teams, ongoing communication with those teams as guidance becomes available, implementation of a suitable system to monitor arrangements and collect relevant data and consideration of standard and bespoke terms and conditions with clients and counterparties.

Compliance with DAC 6 is a large task, both in terms of identifying historic reportable transactions (to the extent that this has not already been done) and ensuring that processes are in place for compliance going forward. Banks should not be assuming that they will be compliant just by virtue of the involvement in their transactions of other intermediaries such as lawyers and accountants. Rather they should be actively monitoring arrangements to ensure that the necessary reports are made with respect to any transactions they are involved with.

Publication

Artificial intelligence (AI) raises many intellectual property (IP) issues.

Publication

We are delighted to announce that Al Hounsell, Director of Strategic Innovation & Legal Design based in our Toronto office, has been named 'Innovative Leader of the Year' at the International Legal Technology Association (ILTA) Awards.

Publication

After a lacklustre finish to 2022 when compared to the vintage year for M&A that was 2021, dealmakers expected 2023 to see the market continue to cool in most sectors, in response to the economic headwinds of rising inflation (with its corresponding impact on financing costs), declining market valuations, tightening regulatory scrutiny and increasing geopolitical tensions.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2023