Publication

Asia M&A trends: Future outlook

Whilst global M&A rose in deal value terms in 2024, both deal values and volumes fell in most parts of Asia.

Author:

Australia | Publication | 10月 2023

Deteriorating economic conditions – driven by persistent high inflation and the consequent tightening of monetary policy, changing work and consumer behaviours post-COVID and heightened geo-political tensions – have contributed to increased levels of financial distress across business.

Retail, commercial and industrial tenants have all felt the impacts of these more challenging economic conditions and many are in turn, facing their own distress and in some cases, possible insolvency.

While there are often warning signs of distress, the precipitation into a voluntary administration can often occur with minimal warning to the landlord. For example, a tenant that loses support from its financier will often move very quickly into external administration. It is therefore crucial to grasp the implications of such situations and be armed with the necessary knowledge to navigate the administration process.

In this three-part series, we present a guide tailored specifically to landlords confronting tenant voluntary administration. Our aim is to provide insights as well as valuable practical steps that will enable you to protect your interests and optimise your outcomes in a tenant voluntary administration scenario.

Voluntary administration is the most common formal insolvency process used to attempt to restructure a distressed business.

The purpose of voluntary administration is to maximise the prospects of a company continuing in existence, or at the very least, achieving better returns to creditors than would be achieved if the company had been placed immediately into liquidation. The main outcomes resulting from the voluntary administration are that:

An administrator can be appointed by: the company itself (if the directors are of the opinion that the company is insolvent, or is likely to become insolvent at some future time); a secured creditor with security over all of the company’s assets (if the security is enforceable); or, rarely, a liquidator.

On appointment, a voluntary administrator assumes control of the company and begins to investigate its affairs. The administrator displaces the directors and has powers of the company’s directors to manage its affairs and deal with its assets.

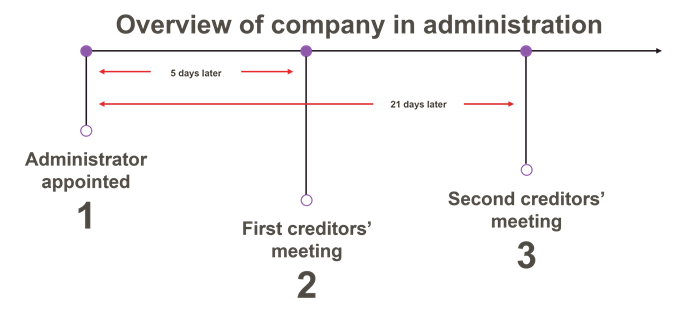

Within 8 business days after the appointment, the administrator will hold a meeting of creditors convened at least 5 business days before. The only items of business are to vote on an alternative administrator if proposed, and to determine if there is to be an advisory committee. Effectively, the meeting often serves to confirm the initially appointed administrator and provide a forum for a preliminary discussion of the circumstances leading to the appointment of the administrator and what might be expected before the next meeting.

Following this meeting, the administrator will continue investigations in order to decide if the creditors’ interests would be best served by considering a DOCA (if proposed), winding up the company, or (rarely) terminating the administration.

The administrator must then hold another creditors’ meeting. This meeting will usually be held 21 days from the beginning of the administration, but may be extended by Court order. When it convenes the second meeting, the administrator must send the creditors a notice, a report of the company’s affairs and a statement explaining what the administrator considers to be the best course of action for the company.

Note: The 21 days for the second creditor’s meeting can be extended by order of the Court.

If a DOCA is proposed, the administrator’s statement must include details of the arrangement and whether it is recommended for creditors. At the second meeting, the creditors can decide whether the company should execute the DOCA, the administration should end or the company should be wound up (i.e. go into liquidation).

Where a business operates from leased premises, the way in which the administrator manages the company’s leasing obligations will be a critical focus. Landlords are invariably key stakeholders in any administration and obtaining their buy-in to any trading, sale or restructuring plan pursued by the administrator is generally a prerequisite to value preservation.

When a tenant enters into administration, legislative requirements trigger a statutory “stay” which prevents landlords from enforcing against leased property while the administration is on foot – landlords are prevented from exercising the remedies of distress for rent; taking possession of the leased property; or to otherwise enforce their security interest in the leased property.

Additionally, for most leases entered into after 1 July 2018, in addition to the stay on enforcement actions, the landlord cannot terminate, or exercise any other right under the lease, if the trigger for doing so is merely the appointment of an administrator to the tenant or its financial circumstances.

There exist a number of exceptions to these restrictions on enforcement and exercise of contractual rights. In appropriate circumstances, the administrator may consent or the Court may grant leave to enforce or exercise contractual rights.

These restrictions are balanced out by a regime which can impose personal liability on the administrator for rent. In the first 5 business days of the administration, the administrator may effectively retain the leased property “rent-free” (subject to the proof of debt procedure mentioned below). After that, the administrators are personally liable for rent or other amounts attributable to the administration period.

However, that personal liability can be avoided if the administrator gives the landlord a notice stating that the company does not propose to exercise its rights in relation to the leased property (No Personal Liability Notice). The landlord is able to recover its leased property upon receipt of a No Personal Liability Notice. The case law suggests that, particularly where there may be a dispute about the landlord’s rights to re-enter the premises under the lease, the landlord should not rely solely on such a No Personal Liability Notice but also obtain the administrator’s written consent to re-enter the leased premises.

|

Case study The case of Markham Real Estate Partners (KSW) Pty Limited v Misan [2022] NSWSC 733 (which was upheld on appeal) related to a dispute in respect of the premises at which operated the Kobe Jones restaurant in King Street Wharf, Sydney. The tenant went into administration on 2 May 2019. Shortly after appointment, the administrator sought to negotiate a rent-free period with the landlord (Markham). This was proposed to facilitate ongoing trading during the administration as part of an effort by the administrator to market the business for a potential sale. However, the landlord declined the proposal and requested the administrator’s consent to take possession of the premises. On 9 May 2019, the administrator provided a No Personal Liability Notice. The landlord relied on that No Personal Liability Notice and subsequent correspondence with the administrator which the landlord interpreted as the administrator’s consent to re-enter the premises. The personal guarantor of the tenant (Misan) contended in the proceedings that the landlord was not entitled to re-enter because the administrator had not consented to the landlord’s re-entry. The Court found against Misan and held that the correspondence with the administrator, properly construed, constituted consent by the administrator to re-enter the premises. |

While a No Personal Liability notice terminates the administrator’s personal liability, the liabilities of the tenant under the lease remain, albeit subject to the proof of debt regime which might arise in any DOCA or liquidation which ensues. This is the conventional position. However, in recent years, accelerated by extended pandemic lockdowns, administrators in larger and more complex administrations have increasingly sought to (further) limit their personal liability by obtaining Court extensions in the Federal and State Supreme Courts of the “rent-free” period (beyond 5 business days) before they incur personal liability or must relinquish the leased property.

A related development has been the emergence of claims made by landlords, even where the administrator has been relieved of statutory personal liability, for rent payable during the administration period to be paid in priority to the claims of ordinary unsecured creditors. This they seek to do under the so-called “Lundy Granite” principle (arising from a 19th Century English liquidation case of the same name). We will explore the issue of protecting rent priority over the claims of ordinary unsecured creditors in part 2 of this series.

At the end of the administration, the restrictions on enforcement and exercise of contractual rights are lifted and the landlord can usually recover its leased property and enforce its rights under the lease. However, if there is a DOCA, the situation can sometimes be more complex and there can be restrictions upon a landlord’s enforcement rights if the landlord is otherwise “adequately protected.” We will explore the potential ramifications of a DOCA and the concept of “adequate protection” in part 3 of this series.

It is not uncommon for a landlord to be granted a security interest under the Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (Cth) (PPSA), particularly where there is a fit out as part of the leased property. Except for short-term leases, any such security interest needs to be perfected, which normally means a registration made by the landlord on the Personal Property Securities Register (PPSR). Failure by the landlord to perfect a security interest can result in unenforceability, with the relevant property becoming the property of the tenant if an administration occurs. Also, even if the security interest is properly perfected, the abovementioned restrictions may apply to it, unless security has been taken over all or substantially all of the tenant’s assets.

It is common for the company directors of tenants, particularly those who are small and medium enterprises, to provide personal guarantees of lease obligations. During the period of the voluntary administration, there is a moratorium on enforcement of directors’ guarantees. This moratorium prevents enforcement during the administration.

The voluntary administration process is designed to maximise the prospects of a company continuing in existence, or at the very least, achieving better returns to creditors than would be achieved if the company had been placed immediately into liquidation.

As such, it is important to quickly develop an understanding of the administrator’s commercial intentions. In particular, whether the administrator intends to continue trading the tenant’s business and whether there are any viable prospects of a sale, recapitalisation or restructuring of the tenant’s business.

With a good understanding of these matters, a landlord will be able to better assess the best commercial and legal response to the voluntary administration. Especially with continued trading, establishing and maintaining ongoing dialogue with the administrator will be important to be able to be across any new developments during the administration.

1. Exceptions to restrictions on exercise of contractual rights

There are a number of exceptions that apply to the administration period restrictions on the exercise of contractual rights. Included in these exceptions are rights of set-off and combination.

Also, if there is a continuing performance breach or payment default which entitles the landlord’s exercise of contractual rights, the restrictions on contractual rights do not apply to enforcement based on those kinds of default.

As such, it is important to consider the basis for any potential exercise of contractual rights or exceptions that would allow for the exercise of the relevant contractual rights. This is particularly pertinent to the extent that reliance on a bank guarantee is premised upon a contractual default.

|

Bank guarantees Tenants entering into commercial leases typically have to provide some form of surety to the landlord to cover the risk of their defaulting on the lease or the landlord having to ‘make good’ the premises, before offering the premises to the market. Under these arrangements, the landlord is usually entitled to call upon a bank guarantee that it holds to reimburse it for rent or other costs owed by the tenant arising from its default under the lease. To the extent that calling upon the bank guarantee is based upon a contractual right in the lease to do so, it is important not to contravene the restrictions on the exercise of contractual rights described above. This will typically mean that the landlord will have to await the completion of the administration – if the company goes into liquidation or there is a DOCA, the landlord will ordinarily be free at that point to cash in the guarantee. If the company ends up in liquidation, the liquidator will investigate pre-liquidation transactions to ascertain whether any of them are voidable as unfair preferences or uncommercial transactions. As a bank guarantee is a guaranteed payment from a third party (the bank) and not the tenant, receipt of the guaranteed funds by the landlord is not considered an unfair preference. |

2. Taking all asset security

All asset security holders are exempt from the restriction on enforcement so long as they commence enforcement action during the first 13 business days of the administration. This window for enforcement can be extended with administrator consent. Where the administrator has been appointed by directors, it is common for all asset security holders to obtain such a consent early in the administration – this gives the security holder ongoing optionality around enforcement during the administration depending on how the administration evolves.

Examples of when a landlord may take all asset security include where the tenant is a special purpose vehicle whose main business function is to hold the lease or the tenant’s entire business operates at the leased site and there is a valuable fit-out over which the tenant grants the landlord a PPSA security interest.

As noted above, perfecting a PPSA security interest is critical to its enforceability. Therefore, it is important to ensure correct registration of a security interest on the PPSR by the landlord. It is best to have the proposed financing statement checked or alternatively to have legal advisers make the registration for you. Timing is also important. For landlords, that normally means having the registration made within 20 days of the date of the lease.

Publication

Whilst global M&A rose in deal value terms in 2024, both deal values and volumes fell in most parts of Asia.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025