Publication

Legalseas

Our shipping law insights provide legal and market commentary, addressing the key questions and topics of interest to our clients operating in the shipping industry, helping them to effectively manage risk.

Indonesia | Publication | avril 2019

Indonesia is targeting that 23 per cent of electricity will be generated from renewable energy sources by 2025.

Hydro, geothermal, solar PV, wind, biomass, biogas and waste-to-energy. Hydro accounts for 7.17 per cent of the total electricity generation (approximately 4,010 MW), with geothermal responsible for another 3.48 per cent (1,948.5 MW).

PT PLN (Perero) (Perusahaan Listrik Negara or state electricity company) (PLN) is the state-owned vertically integrated utility company who acts as the primary offtaker of electricity generated by independent power producers (IPPs).

Consumers are allowed to own and operate power generation facilities for their own use and may sell any excess power to PLN. Consumers wishing to do this need to comply with prevailing regulation and will need approval from PLN. See below for a discussion of rooftop solar and net metering.

Private parties are also allowed to set up IPPs and to sell the electricity generated directly to end-users within a stipulated area. Key requirements of such projects include an electricity supply business permit, an operational license (izin operasi), a designated operating area (wilayah usaha) and approval of the tariff by the relevant authority.

Indonesia favours an auction process with a tariff ceiling. Projects are procured under differing methods, according to the renewable energy source/technology. These are explained below.

Renewable projects (other than geothermal and waste-to-energy)1

With the exception of geothermal and waste-to-energy projects, all renewable projects must be procured by PLN through a “Direct Selection” process, which is a limited tender process involving at least two bidders drawn from a pre-qualified list.

During the pre-qualification phase, developers are invited to join a “List of Selected Providers” (Daftar Penyedia Terseleksi or DPT). According to PLN, the List of Selected Providers is valid for a period of three years.

PLN has concluded two pre-qualification processes so far. The first was launched in October 2017 for developers of solar PV, hybrid energy, wind, biomass and biogas, municipal waste and tidal projects. The results were announced in November 2018 and the pre-qualification is valid for three years. The second pre-qualification process was launched in April 2018 for hydro projects (above 10 MW).

PLN commenced a third pre-qualification process for developers of solar PV, hybrid energy, wind, biomass, biogas, tidal, biofuel and “new energy” projects about 10 MW in 2019. “New Energy” is defined under Law No. 30 of 2007 on Energy to cover nuclear, hydrogen, coal bed methane, liquefied coal and gasified coal. The deadline for submission of applications was on March 15, 2019 and the pre-qualification status granted by this process will be valid for three years.

Pre-qualification processes have also been carried out by PLN at a regional level for renewable projects below 10 MW.

Specifically for solar PV and wind power, the direct selection process must be based on a “capacity quota” – being the maximum generation capacity offered to business entities within a certain period of time for a determined purchase price.

Geothermal2

The central government, through the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR), has authority to tender geothermal working areas. The tender process is a two stage process consisting of a qualification stage followed by the submission of a project development proposal and an exploration commitment proposal. The size of the exploration commitment determines the winning bidder, who is entitled to receive a geothermal licence or Izin Panas Bumi or IPB. After successful exploration the IPB holder will enter into a power purchase agreement (PPA) with PLN based on the terms disclosed to the IPB holder at the bidding stage.

Waste-to-energy

Waste-to-energy projects may be procured by the governor or mayor of the following cities: DKI Jakarta, Tangerang, Bandung, Semarang, Surakarta, Surabaya, Makassar, South Tangerang, Bekasi, Denpasar, Palembang and Manado. Potential projects are procured by way of public tender under the government procurement rules or PPP rules. The selected developer enters into a waste management agreement with the local government and a PPA with PLN.

Tax incentives.

Waste-to-energy projects are eligible for FiTs (as discussed below).

Indonesian law establishes a tariff ceiling for renewable energy, which is set by reference to a percentage of PLN’s cost of generation for the prior year, including its own generation and the power procured from IPPs, but excluding the cost of electricity distribution. This is referred to as the Cost of Generation or the Indonesian acronym, BPP.

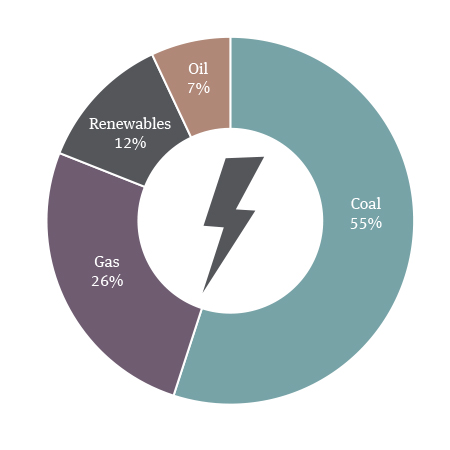

Given Indonesia’s energy mix, fossil fuel prices (and the exchange rate fluctuations that apply to them) are a key determinant of the BPP and therefore renewable energy tariffs. Given that Indonesia has capped coal prices for electricity generation, this may have a limiting impact on the BPP going forward.

The MEMR publishes annual figures for the BPP, which include a national average as well as averages for each locational specific sub-system. The 2018 figures, published in April 2019, are used to determine the tariff ceilings for the period from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020. The 2018 national average BPP was USD 7.86 cents/kWh or IDR 1,119/kWh.

If the average cost of generation of the local grid is higher than the national average, the tariff may reach up to 100 per cent of the local BPP for municipal waste, hydro and geothermal and 85 per cent of the local BPP for other renewable technologies. If the local BPP is less than or equal to the national average, the tariff will be determined by agreement between the developer and PLN on a bilateral basis. In practice, however, PLN seeks to cap the tariff in these scenarios as well.

Once the tariff is agreed with PLN, it must be approved by the MEMR prior to the signing of the PPA. The tariff is locked in once the PPA is signed and that rate will not be adjusted year on year.

Tariffs for recent renewable projects have ranged between USD 8 – 11 cents/kWh.

Waste-to-energy

Waste-to-energy projects are subject to a FiT3 of:

< 20MW US$13.35 cents/kWh

> 20MW determined based on the formula of 14.54 – (0.076 x capacity)

MEMR Regulation No. 49 of 2018 (Regulation 49) regulates the development, ownership and operation of on-grid capture solar generating facilities. Regulation 49 does not expressly apply to off-grid installations, but the MEMR has stated that Regulation 49’s requirements will apply to on and off-grid projects.

PLN’s customers are permitted to install and operate rooftop solar projects for their own use and sell excess power generated to PLN on the basis of a net metering scheme, subject to a 35 per cent discount. If the power supplied to the grid exceeds the imported energy in a month, any credit owing to the consumer is set-off against the consumer’s electricity bills in subsequent months within the same calendar quarter.

Among other requirements, developers of rooftop solar projects must obtain prior approval from PLN for the system design and are subject to a cap on the installed capacity being 100 per cent of the consumer’s connected capacity based on the total capacity of the inverter.

If industrial owners of rooftop solar installations wish to remain connected to the grid, they must pay parallel operation charges to PLN consisting of a connection charge, energy charge and a capacity charge, which is based on a minimum monthly take-or-pay obligation of 40 hours.

IPPs are required to set up a limited liability company established under Indonesian law and domiciled in Indonesia. As a general rule, an Indonesian limited liability company must have at least two shareholders.

Foreign shareholding restrictions apply under Indonesia’s current Negative Investment List as follows

<1 MW closed to foreign ownership

1–10 MW up to 49 per cent foreign ownership

>10 MW up to 95 per cent foreign ownership or 100 per cent foreign-owned if the project is procured under the Public Private Partnership (PPP) scheme.

Prior to the commercial operation date, transfer of shares in a non-geothermal IPP is restricted, except to a 90 per cent owned affiliate of the sponsor established in Indonesia. From the commercial operation date, a transfer will be subject to approval from PLN and must be reported to the MEMR.

Shareholders of a privately held geothermal IPP can transfer their shares, but must notify MEMR shortly thereafter.

Previous projects have been project financed mostly by international banks, export credit agencies and multilateral agencies, but domestic banks have also participated in some financings.

PLN must provide the template PPA for each type of renewable energy project at the time of procuring the project.

The forms of PPA vary from project to project, but are broadly based on the same set of terms. PPAs for small renewable projects tend to receive a short form PPA, whereas larger scale projects are subject to a longer (and more bankable) form of PPA.

Traditionally, the long form PPAs have been viewed as bankable and the market has come to expect key features such as relief for political force majeure and grid related force majeure, including deemed commissioning and deemed dispatch.

Regulations first introduced in 2017 (and amended in 2018)6 (Regulation 10), however, have prescribed the contents of PPAs for dispatchable power projects, including geothermal, biomass and hydro. The regulations do not apply to intermittent power projects (wind and solar), mini-hydro (below 10 MW), biogas and water-to-energy. The projects covered by Regulation 10 must now be structured as a BOOT project. The regulations have created uncertainty about the traditional Indonesian PPA risk allocation. Key concerns centre on the risk allocation for grid force majeure, deemed dispatch payments, change in law and currency for payment.

The PPA term must not exceed 30 years from the commercial operation date.

In general, PLN pays deemed commissioning payments if the IPP is unable to conduct a commissioning test due to any actions or failure to act by PLN without justifiable cause, political force majeure, or natural force majeure affecting PLN’s grid or other grid damage events (subject to a specified grace period). Key exceptions to this risk allocation are

In general, PLN pays deemed dispatch payments if PLN is unable to accept energy due to natural force majeure affecting PLN’s grid or other grid damage events (subject to a specified grace period) or where political force majeure affects the IPP’s ability to deliver energy. Key exceptions to this risk allocation are

However, the IPP is entitled to an extension of the term of the PPA to compensate for periods of inoperability due to qualifying events.

For hydro, geothermal and biomass PPAs, PLN will be subject to a take-or-pay commitment for a specified period. In practice, this tends to be consistent with the tenor of the debt.

For other renewable technologies, PLN is subject to a take-or-pay commitment for the term of the PPA.

Traditionally, Indonesian PPAs have provided for deemed dispatch payments if the IPP is unable to generate due to a change in law and an adjustment of the tariff for changes in law that affect the costs of generation.

In our view, Regulation 10 (which applies to hydro, geothermal and biomass PPAs) does not restrict PLN’s ability to continue with this policy. However, it is not yet clear whether PLN shares this interpretation.

PPAs for utility scale projects specify international arbitration under ICC rules with a seat in Singapore. Small scale projects (including mini-hydro) tend to provide for domestic arbitration i.e. the Indonesian National Arbitration Centre (Badan Arbitrase Nasional Indonesia or BANI).

PLN does not provide credit support.

Traditionally, Indonesian IPPs had the benefit of a government support letter, but this is becoming increasingly difficult to obtain. Recent project financings have successfully closed without government support, including the financing for the Java 1 LNG-to-power project.

Theoretically, government support is available in two different forms. Renewable projects may be eligible for a Business Viability Guarantee Letter (BVGL) issued by the Ministry of Finance.

If the IPP is procured under the PPP regulations (which is less common) it may be eligible for guarantees issued by the Indonesian Infrastructure Guarantee Fund (IIGF) and the Ministry of Finance.

Land acquisition is the primary issue. PLN generally expects developers to acquire all of the land needed for the plant site and the transmission lines needed to connect the plant to the nearest substation. It is common for the transmission corridor to be 20 to 40 kilometres long. PLN and lenders generally expect this land to be obtained and appropriate legal rights over that land to be granted by the financial closing date. The process of land acquisition can often be one of the longest lead items in the development of an Indonesian power project.

The number of permits and licenses to be obtained from various authorities, including from the central and the local governments, are onerous. Forestry related permits, for example, can take a significant period to obtain.

Indonesian law specifies that the tariff must be paid in local currency (Rupiah or IDR). IPPs that have reached financial close in recent years have found a work-around for this problem, but Regulation 10 has created uncertainty around this issue.

Publication

Our shipping law insights provide legal and market commentary, addressing the key questions and topics of interest to our clients operating in the shipping industry, helping them to effectively manage risk.

Publication

Our 23rd report spotlights landmark legislative reforms such as the UK’s new Arbitration Act 2025 and South Africa’s rise as a regional arbitration hub. We examine procedural innovations, enforcement challenges, and the evolving role of tribunals in promoting settlement.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025