Publication

Foreign Subsidies Regulation: Year 2 of EU’s newest trade defence tool

This year, is expected to be as active as 2024, providing further clarity on both the obligations of notifying parties and the EC's review methodology.

Mondial | Publication | July 2016

The world of international tax rarely moves quickly. However, with the shift in public opinion towards tax avoidance following the financial crisis, various governments and international organisations have moved with unprecedented pace to introduce new rules governing the way cross-border transactions and arrangements are taxed. Here, we look at the background to some of the coming changes and, in particular, on those measures that are most likely to have an impact on the aviation industry.

It is worth starting by defining what we mean by “international tax”. In this context, we mean the body of tax law that governs the way transactions involving one or more countries are taxed between those countries. This includes a mixture of international law (such as double tax treaties concluded between two countries) and domestic provisions (such as the UK’s own transfer pricing rules).

It has always been a general principle of international law that countries are responsible for their own revenue-raising; however, this autonomy has led over time to mismatches in the way different jurisdictions have treated the same transaction. In fact, it is arguable that some jurisdictions have adapted their own rules to exploit these differences and encourage transactions to take place through their jurisdiction.

Broadly speaking, the international law provisions are generally aiming to allocate taxing rights in respect of a particular item of income or gain between two countries that have an interest in a transaction in order to balance the rights of the two countries involved. Domestic measures tend to try and unilaterally protect a country’s tax base.

In each case, the rules are trying to prevent multinational groups from either shifting profits from a jurisdiction where they would be subject to a high tax rate to a jurisdiction that taxes them at a lower rate (or not at all) or from reducing the amount of profit subject to tax in its jurisdiction of operation by paying excessive tax deductible amounts in order to reduce its tax base.

The term now universally given to the activities described above is “base erosion and profit shifting”, which is shortened to BEPS.

As part of these measures, tax authorities worldwide are also formulating plans to obtain information from taxpayers which can then be shared between tax authorities in different jurisdictions. This process began with the introduction of FATCA by the US and has been developed since by the OECD and individual countries such as the UK. It is therefore becoming increasingly difficult for taxpayers to rely on the fact that a tax authority in one jurisdiction will not be able to access details of how a particular transaction is viewed in another jurisdiction.

With the growth in online business and the increase in international mobility, these measures are now of high importance to the jurisdictions concerned and, whilst aviation will not be the primary target of such measures, the international nature of the business means that airlines, lessors and financiers will need to be aware of the possible implications of the changes of rules on their businesses.

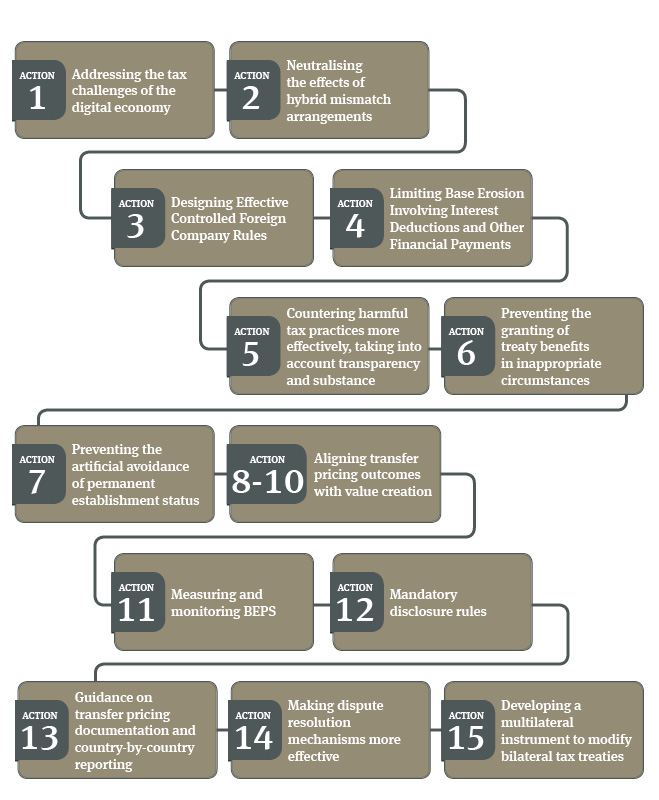

Since 2012, the OECD has been working on 15 action plans which introduce recommendations for how jurisdictions could implement rules to combat BEPS. The final recommendations on these 15 action plans were published in October 2015.

Separately, the EU published in January 2016 a draft directive that recommends minimum standards for EU member states in relation to various tax avoidance techniques. These overlap to some extent with the OECD BEPS proposals, although there are some other recommendations that are specific to the way EU member states should implement their own domestic tax rules on cross-border transactions.

The OECD action plans are:

Of the action plans set out above, a number of them are aimed at the way multinational groups structure themselves. Airlines often find themselves with complicated group structures and they will need to assess whether any of the provisions that are apparently targeted at international companies operating in the digital economy will actually be applicable to intra-group transactions within their own groups.

In particular, these measures are likely to include measures under Action 2, Action 3, and Actions 7-10, which in the main relate to transfer pricing between group entities or allocating profits to group entities in lower tax jurisdictions. Whilst airlines might well have intra-group transactions that may fall within some of these types of structure, the fact that most airlines operate out of a large fixed base in their principal country of operation, and that aviation profits tend to benefit from specific double tax treaty protection in a large number of cases, means that these are less likely to have a significant impact on the group structure of most airlines. However, airlines will need to monitor these rules as they are introduced in order to ensure that their intra-group arrangements are not caught in the cross-fire.

Airlines increasingly sell tickets and services over the internet and will need to be careful that the rules introduced as a result of Action 1 and Action 7 do not cut across their digital marketing and web-ticketing arrangements. Again, aviation business will generally have additional protection as a result of the specific aviation profits article of the relevant double tax treaty although of course this will depend to some extent on the procedures of the relevant counterparty jurisdiction and the approach it takes to the interaction between existing double tax treaties and new rules introduced to counter BEPS.

Finally, it is worth looking at financing transactions. Where an aircraft lessee is based in a jurisdiction that has a withholding tax on aircraft lease rentals, Action 6 is likely to become relevant. The specific recommendations under Action 6 are that double taxation treaties should contain either a limitation on benefits article or a “main purpose” article. This will mean in particular that transactions involving intermediate lessors based in a suitable treaty jurisdiction may come under more scrutiny in the future. It is worth noting that some jurisdictions are already beginning to look at such arrangements and question whether the intermediate lessor has appropriate “beneficial ownership” of the lease rentals for tax treaty purposes. Parties may therefore want to include provisions ensuring flexibility in the event of a rule change as well as suitable protection in the event of a transfer to a party with less substance than the initial parties to the transaction.

Airlines themselves, as well as special purpose lessor entities will need to look out for the rules that will be introduced under Action 4. This action point will restrict interest deductions where they exceed a certain percentage (likely to be 30%) of EBITDA. The rules are likely to be complex, but it is worth noting that, at the time of writing, the UK has just announced it will publish draft rules to be introduced in the Finance Bill 2017. These rules are therefore beginning to be introduced and are likely to have an impact on both airlines and special purpose financing entities. It will be important to monitor these rules as they are likely to be introduced on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis and hence involve a degree of inconsistency in their implementation.

Whilst this area is still an area which is principally a question of “wait and see”, measures are being introduced by different jurisdictions already and it is not something that can be ignored. Parties involved in transactions that may be affected should begin to undertake a risk assessment of the transactions and structures that are most likely to be affected and assess the likelihood of the transaction being affected and whether there is an effective contingency plan.

Publication

This year, is expected to be as active as 2024, providing further clarity on both the obligations of notifying parties and the EC's review methodology.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025