Executive Summary

Organizations that have made long-term net-zero commitments are now expected to develop and deliver on credible and detailed implementation plans.

There are growing expectations that organizations also commit to ambitious near-term targets, and deliver rapid reductions within their own operations this decade.

Many organizations are seeking to drive emissions reductions in their broader supply chain (i.e. Scope 3 emissions). Market leaders are purchasing carbon credits to offset greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that have not yet been eliminated on their pathway to net-zero.

Norton Rose Fulbright is keen to support our clients across all industry sectors to rapidly decarbonize and participate in voluntary carbon markets.

In June 2022, in collaboration with BloombergNEF (BNEF), we invited organizations to complete a brief survey on their decarbonization strategy. In this article, we present the results of our joint survey and the key themes shaping how organizations engage with carbon markets on their pathways to net-zero.

Our key takeaways from the results of our survey are:

- Organizations are prioritizing reducing Scope 1 and 2 emissions, with a strong focus on the procurement of renewable energy.

- It will be a number of years before the international transfer of mitigation outcomes under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement takes off at scale and is accessible to the private sector. Voluntary carbon standards remain the preferred route to market for purchasing carbon credits for many organizations.

- Purchasers of carbon credits can be hesitant to enter into long-term offtake agreements due to risks relating to changes of law and policy. There is nevertheless strong interest in direct investments in carbon projects.

- Our respondents showed lower-than-expected interest in nature-based credits, but a relatively high proportion indicated that co-benefits will influence their choice of carbon credits.

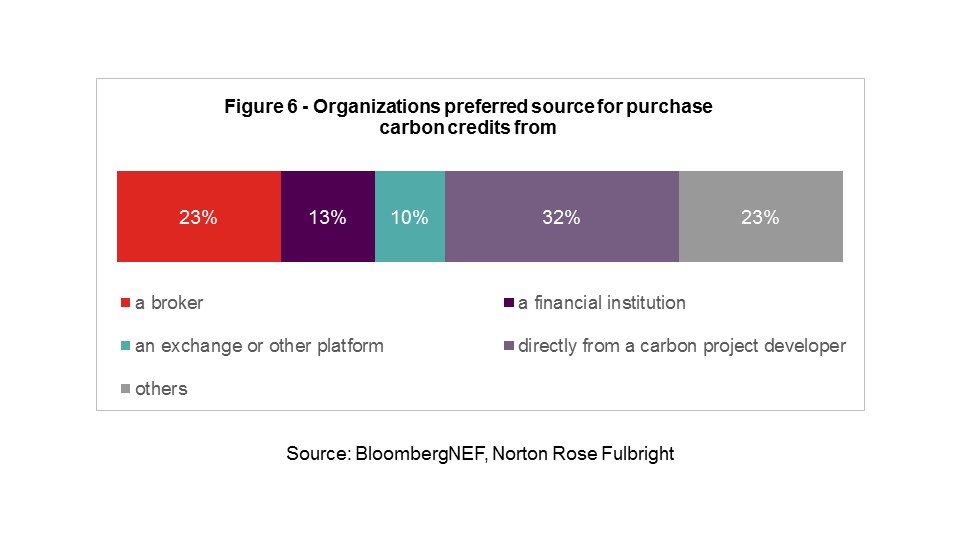

- Purchasers have a preference to purchase directly from carbon project developers, with buying from brokers a second choice.

- A two-tiered market may emerge over the next few years, with voluntary carbon credits that have been authorised for international transfer and subject to a corresponding adjustment under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement considered to be higher quality than carbon credits that have not.

Introduction

In the lead-up to COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, we saw record numbers of organizations join the United Nations Race to Zero Campaign, which now represents 8,307 companies, 595 financial institutions, 1,125 educational institutions and 65 healthcare institutions that have committed to net-zero by 2050.

Fast forward one year, and the focus has turned to implementation. Many organizations are well on their way to finalizing a net-zero implementation plan.

More than 3,900 companies - covering over one-third of the global economy’s market capitalization - are now working with the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) to reduce emissions in line with climate science and the Paris Agreement goals.

Carbon removals have an important role in neutralizing residual emissions that cannot be abated

While organizations are prioritizing reducing GHG emissions from their own operations and supply chain, carbon removals have an important role in neutralizing residual emissions that cannot be abated.

Market-leading organizations are now implementing climate positive strategies. These organizations are not only reducing emissions in accordance with science-based targets, but are neutralizing their emissions profile while on the journey to net-zero. The Voluntary Carbon Market Integrity Initiative has embedded this approach in its proposed Claims Code of Practice.

In this article, we set out our key findings relating to net-zero commitments, carbon credit purchasing strategies and preferences for different types of carbon credits.

Net-zero commitments

Organizations prioritize Scope 1 and 2 emissions reductions, strong focus on procuring renewable energy

Almost 50 percent of respondents have published an implementation plan that aims to deliver their emissions reductions targets or commitments.

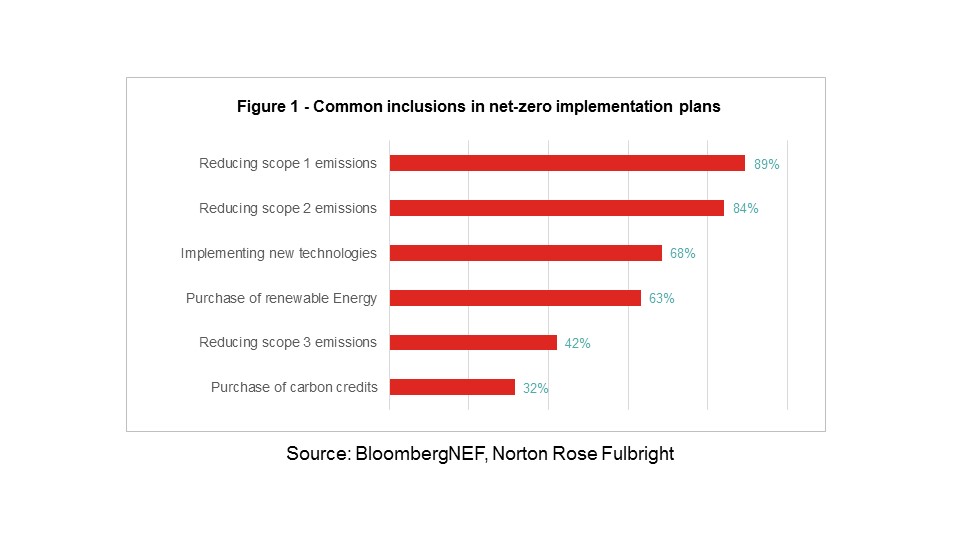

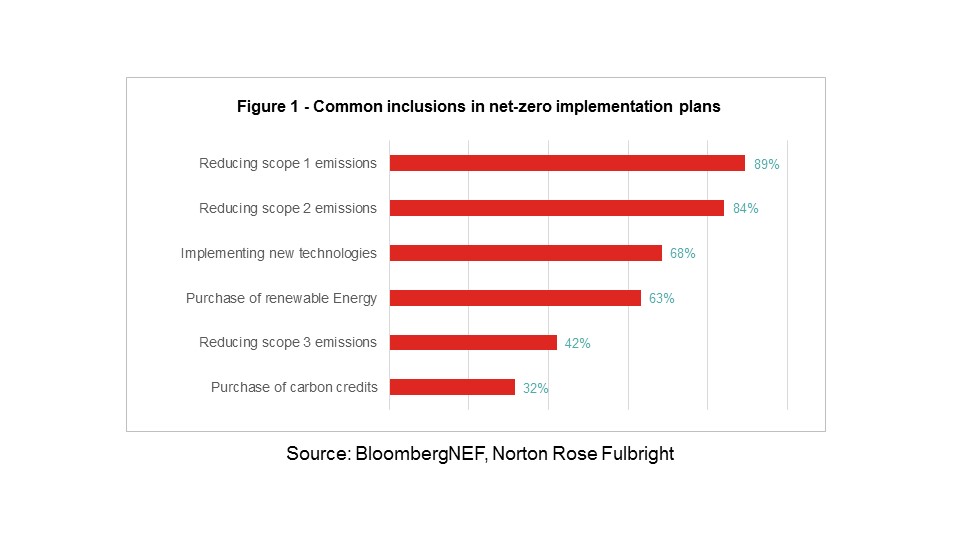

Figure 1 below shows that most of these organizations address Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions reductions in their implementation plans. However, fewer than half organizations address Scope 3 emissions reductions (i.e. reducing emissions in their broader supply chain).

Almost two-thirds of organizations that have published implementation plans intend to purchase renewable energy in order to reduce their Scope 2 emissions, while just under a third of these organizations intend to purchase carbon credits as part of their decarbonization strategy.

This demonstrates that many organizations are prioritizing reducing GHG emissions from within their own operations, and that the procurement of renewable energy is a common strategy to reduce Scope 2 emissions.

The Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) considers that “rapid, deep cuts to value-chain emissions are the most effective and scientifically-sound way of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C.”

The SBTi further provides that carbon credits representing removals should be used to neutralise any GHG emissions that cannot be eliminated by the target year or to finance additional climate mitigation beyond science-based targets.

Nevertheless, we hope to see an increasing number of organizations addressing scope 3 emissions in their net-zero commitments and implementation plans.

We also hope to see a “race to the top” of organizations committing to climate positive strategies. Microsoft is a leader in this regard, having committed to use carbon removals to offset all of its Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions since it was founded in 1975, and be carbon negative by 2030.

The Voluntary Carbon Market Integrity Initiative has embedded this approach in its proposed Claims Code of Practice. Organizations are only able to achieve “VCMI Gold” status if they:

- are on track to achieve interim targets for Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions through emissions reductions within their value chain; and

- cover all remaining emissions through the retirement of carbon credits.

Lack of internal audit and scrutiny of implementation plans and the purchase of carbon credits

Of our respondents that have a documented net-zero implementation plan, 80 percent indicated that internal audit has not reviewed the effectiveness of the plan.

Further, 87 percent of respondents have not yet developed risk and compliance controls for transactions that involve purchasing credits directly from carbon project developers (despite just over 50 percent considering purchasing credits directly from project developers).

This indicates that companies are addressing purchasing of carbon credits via investment in the structure similar to buying a real asset, like a building or a machine, or even a procurement input, like physical oil or power, rather than a product that can change in value or even be declared non-compliant by fiat action of a regulator.

Adoption of risk management techniques regarding valuation, tracking of market structures, and regulatory changes would be appropriate for such long term, high value and high importance investments.

Carbon credit purchasing strategies

Companies know how to procure carbon credits

Demand for carbon credits on the voluntary carbon market is on the rise. Some organizations are spending tens of millions of dollars on the purchase of carbon credits for the purpose of working toward climate and sustainability goals or gaining a competitive advantage with customers.

Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) said that they are comfortable they know how to secure carbon credits.

Somewhat to our surprise, of our respondents that include the purchase of carbon credits in their implementation plan, nearly three-quarters (74 percent) said that they are comfortable they know how to secure carbon credits.

This suggests that accessing the voluntary carbon market is not a significant barrier among participants, which is contrary to the narrative around the need for accessible exchanges and other platforms designed to ensure ease of sourcing carbon units for voluntary purposes. However, our survey did not specifically capture data about whether lack of information was a barrier to other respondents that did not include carbon credits in their implementation plans.

Article 6 still too theoretical for many

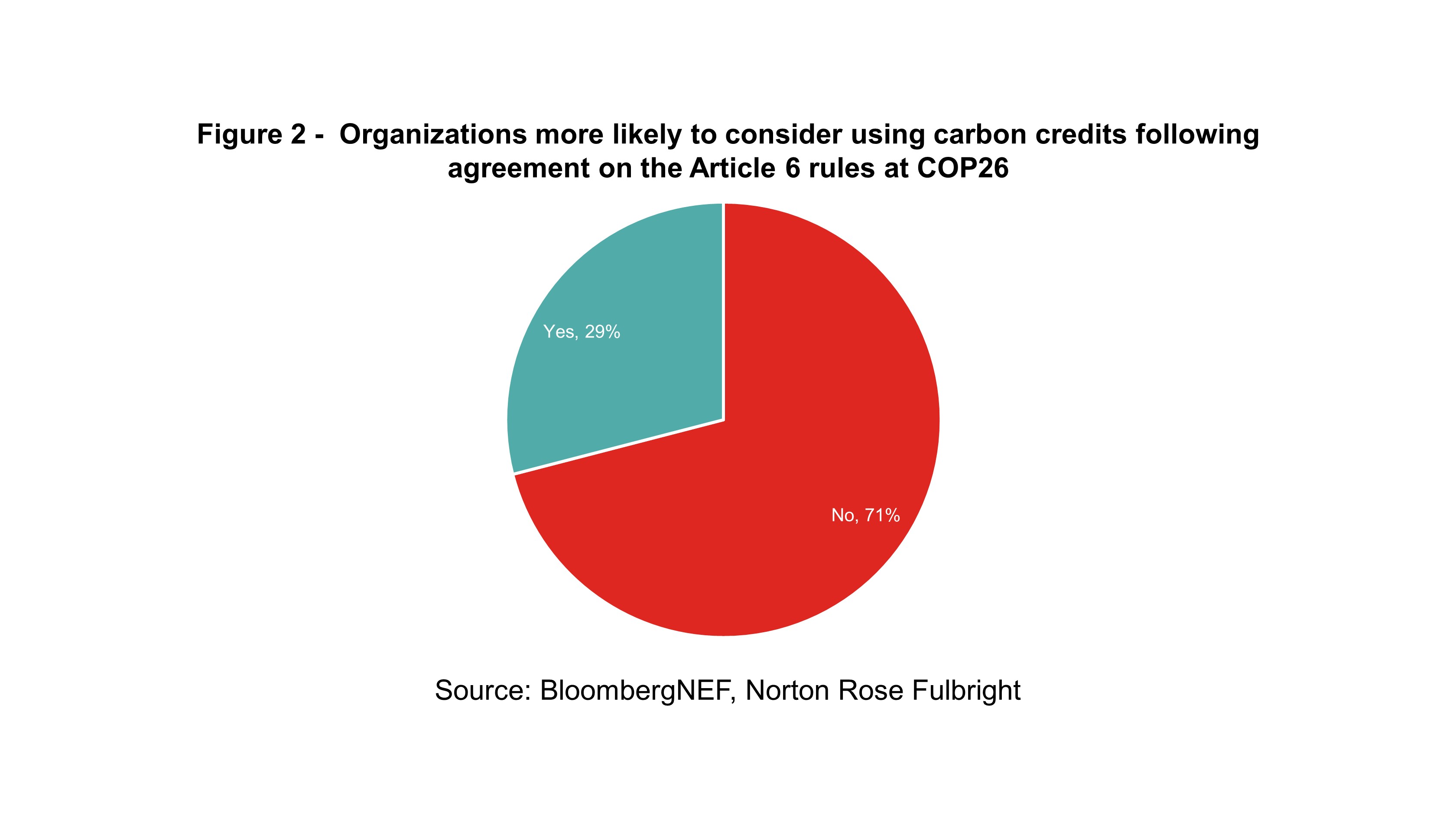

A key outcome from COP26 in Glasgow was agreement on the detailed rules for the new market (and non-market) approaches under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

Nevertheless, it will be a number of years before the international transfer of mitigation outcomes under Article 6 takes off at scale. An extensive work programme remains for 2022 and 2023, including:

- key decisions relating to the establishment of the international registry, Article 6 database and centralized accounting and reporting platform; and

- further steps towards operationalizing the Article 6.4 mechanism.

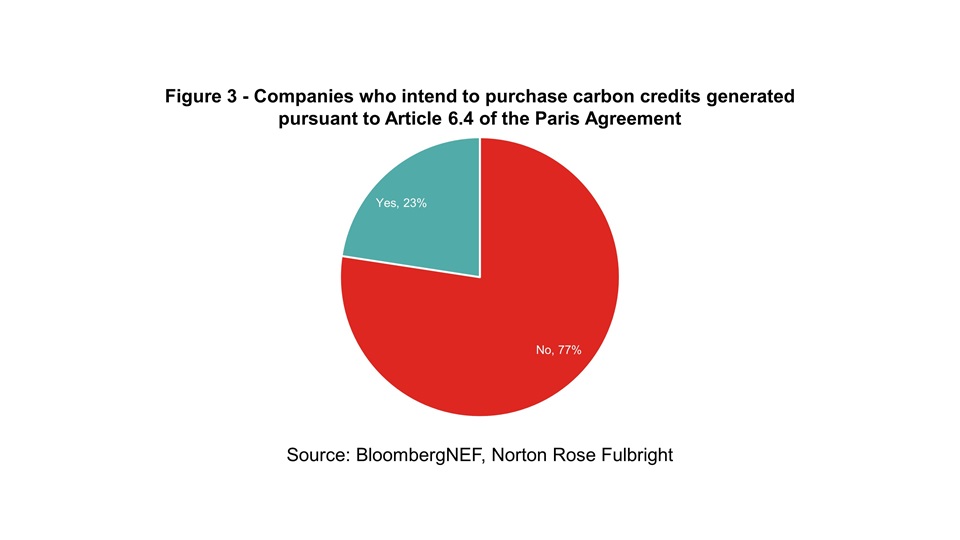

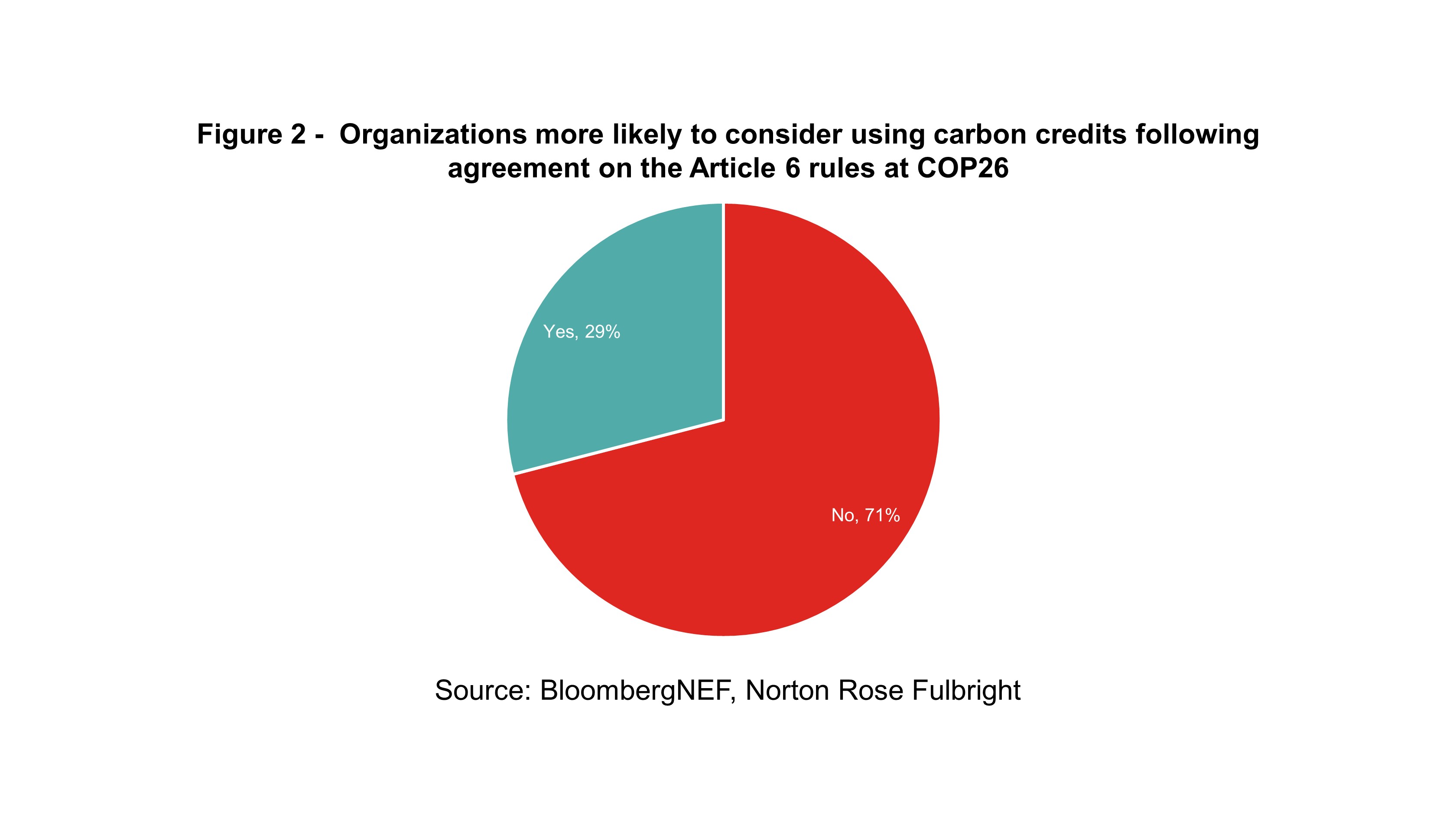

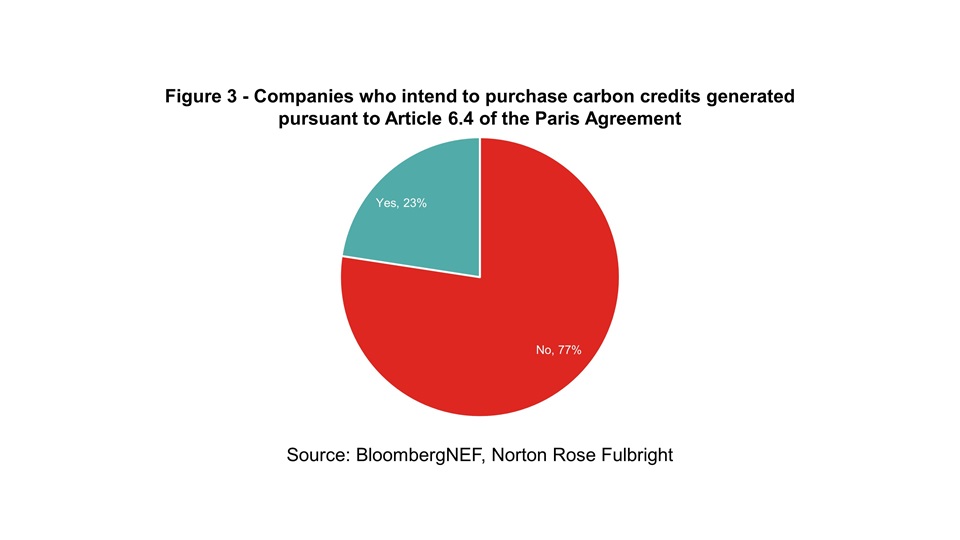

This is reflected in our survey results, with just under a third of respondents saying the agreement on the Article 6 Rules spurred them to consider using and purchasing carbon credits (Figure 2). Even fewer are currently planning to source carbon credits through the Article 6 mechanisms (Figure 3).

NRF and BNEF will closely track developments on Article 6 at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, but it is likely that it will be at least another year before the institutional infrastructure required for Article 6.2 is fully operational, and the Article 6.4 mechanism is able to approve projects and programs.

We are also closely tracking the emergence of bilateral and multilateral approaches under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement. An increasing number of countries have already reached agreements to implement Article 6.2 approaches, led by the Switzerland’s KliK Foundation’s bilateral agreements with Peru, Ghana, Senegal, Georgia, Dominica and Vanuatu.

It is notable that, to date, there have been relatively limited opportunities for private sector involvement under these agreements. However, our clients are increasingly considering options for using Article 6 approaches to support investment into Sustainable Development Goal-aligned projects in developing countries, so we assume this type of activity will increase.

In the meantime, the voluntary carbon market (e.g. Verra’s Verified Carbon Standard and the Gold Standard) remain the preferred route to market for purchasing carbon credits for many organizations.

Limited uptake of long-term offtake agreements

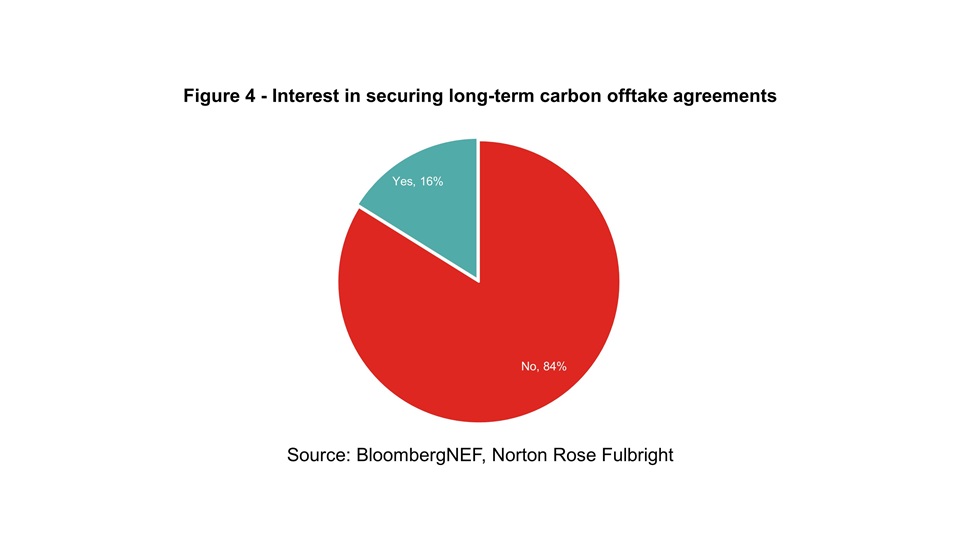

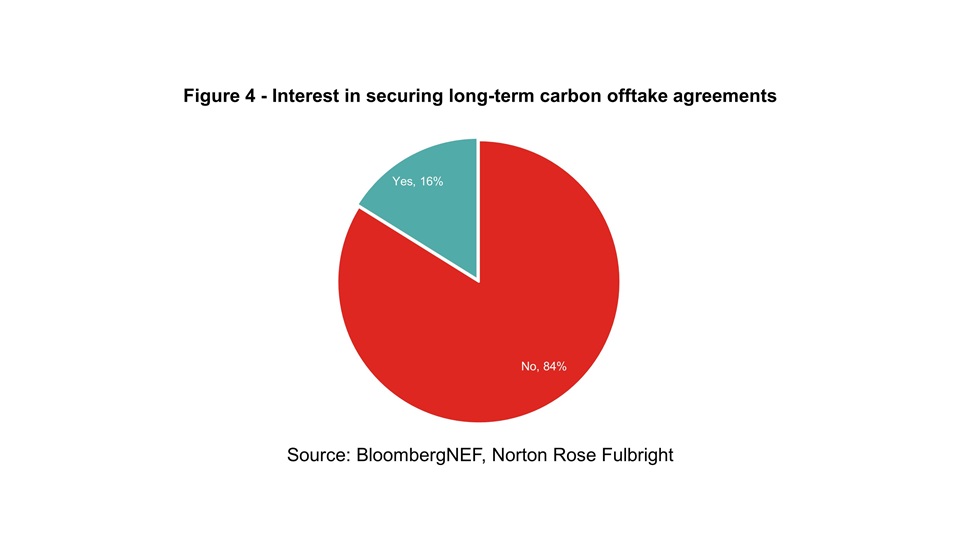

Only 16 percent of respondents indicated that they were considering entering into a long-term agreement for the purchase of carbon credits from a particular project, program or company (Figure 4).

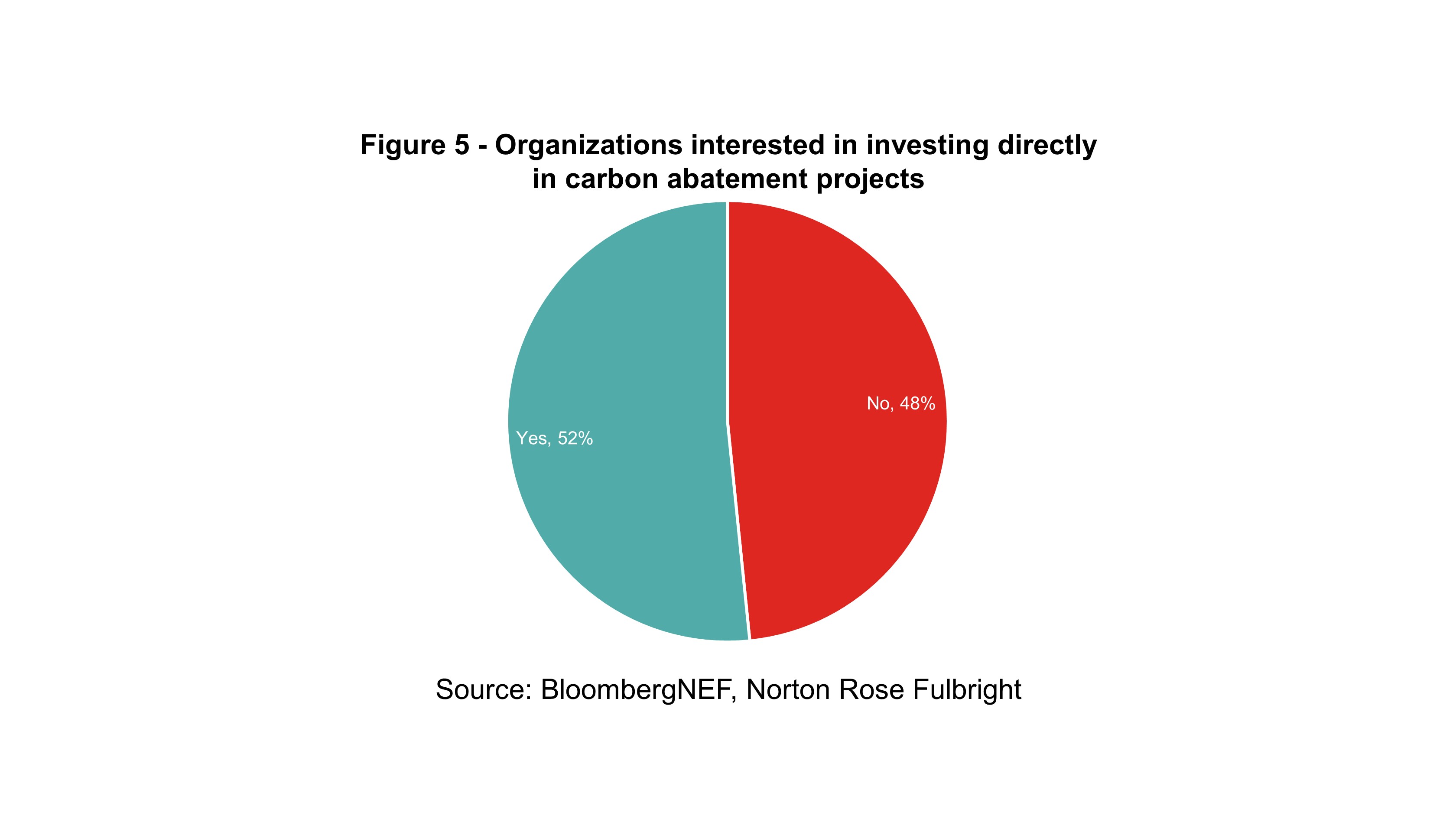

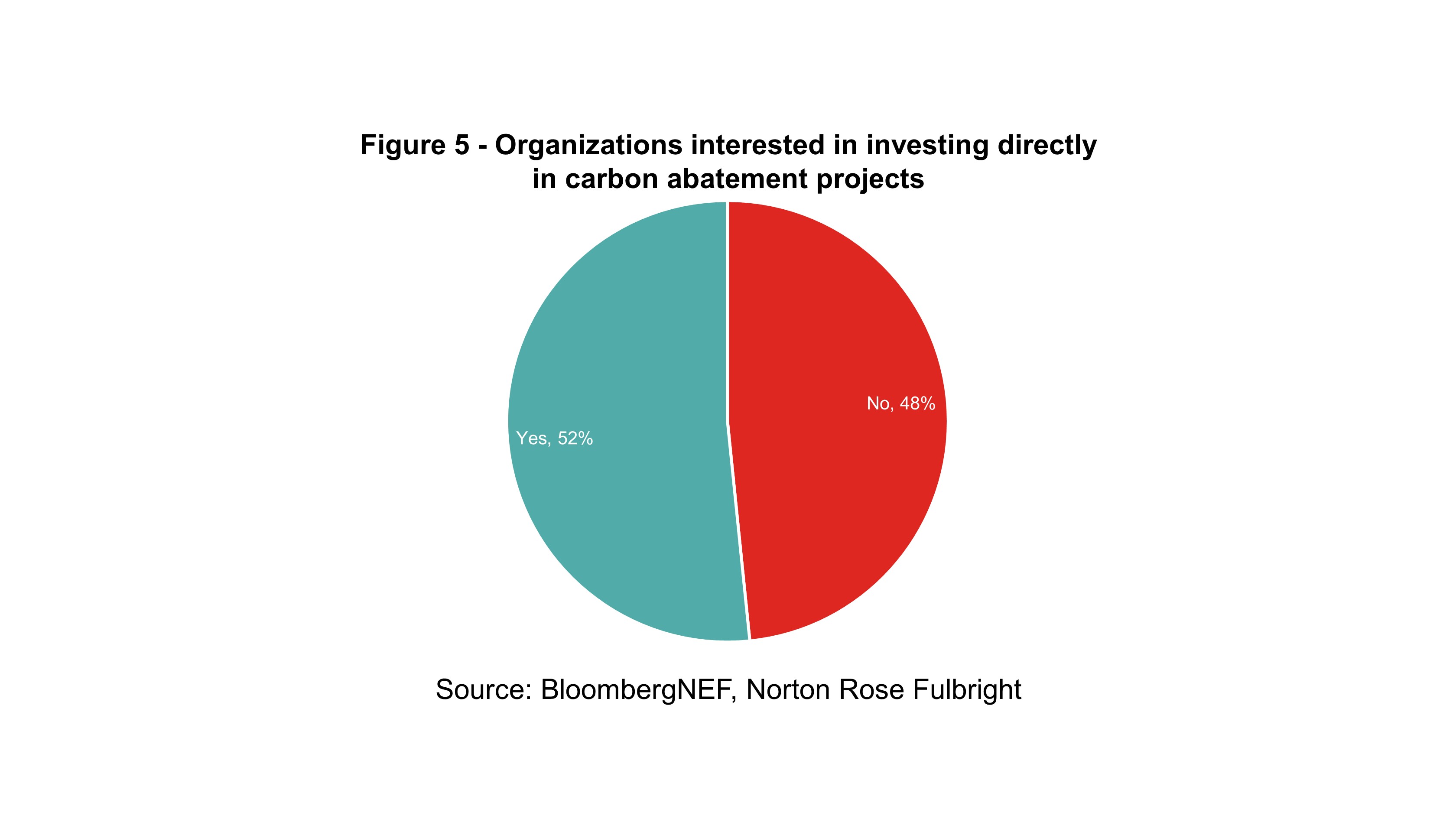

However, over 50 percent of respondents signaled interest in investing directly in carbon projects (Figure 5), which in our experience often involves up-front financing of carbon projects in exchange for long-term carbon credit offtake agreements.

Organizations can often be hesitant to enter into long-term offtake agreements due to risks relating to changes of law and policy, particularly those that may limit or prevent the export of carbon credits from the host country.

This hesitancy may be a downside for project developers, as long-term supply contracts provide a secure source of revenue and reduce the need to continue to seek out additional investors (who may have different demands and requirements).

However, carbon credits are generally considered to be under-priced today. Given that higher future prices are expected, not locking into long-term supply contracts may work out in a project developer’s favor and to a purchaser’s detriment. We were somewhat surprised that more respondents were not considering the future risks associated with lower supply and higher prices of required offsets in terms of their mid- to long-term strategies.

Types of carbon credits

Surprisingly low interest in nature-based carbon credits

We were surprised that only 26 percent of respondents demonstrated a preference for carbon credits generated from nature-based solutions. This is contrary to our experience that many organizations favor nature-based carbon credits, often resulting from the strong environmental and community co-benefits associated with these types of credits.

The lower-than-expected results may be because some respondents are concerned by the risks of non-permanence and reversals of sequestration and the potential for the development of monocultures in certain reforestation projects.

Often, concerns about nature-based removal credits can be addressed through careful due diligence on projects, and in ensuring an appropriate risk allocation in agreements between landholders, carbon project developers and offtakers.

Strong interest in credits with co-benefits

40 percent of respondents indicated that their choice of carbon credits would be influenced by the co-benefits associated with the underlying project.

In our experience, retail and other consumer-facing companies in particular are willing to pay a premium for carbon credits with attractive co-benefits, as a result of customer demand and a broader commitment to alignment with positive Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) outcomes.

For example, clean cookstove projects not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but improve health outcomes through reducing smoke inhalation, and improve livelihoods as a result of saving households time and money. Unsurprisingly, carbon credits generated from projects associated with verified co-benefits can attract a significant price premium.

There is certainly demand for more methodologies to be developed to quantify different kinds of co-benefits

While there are already methodologies that enable the accurate quantification of co-benefits, there is certainly demand for more methodologies to be developed to quantify different kinds of co-benefits, including achievement of Sustainable Development Goals.

Transparent and accurate reporting on the benefits to species and habitats will become particularly important as organizations increasingly focus their attention on addressing the biodiversity crisis, in addition to the climate crisis.

Preference to purchase directly from project developers

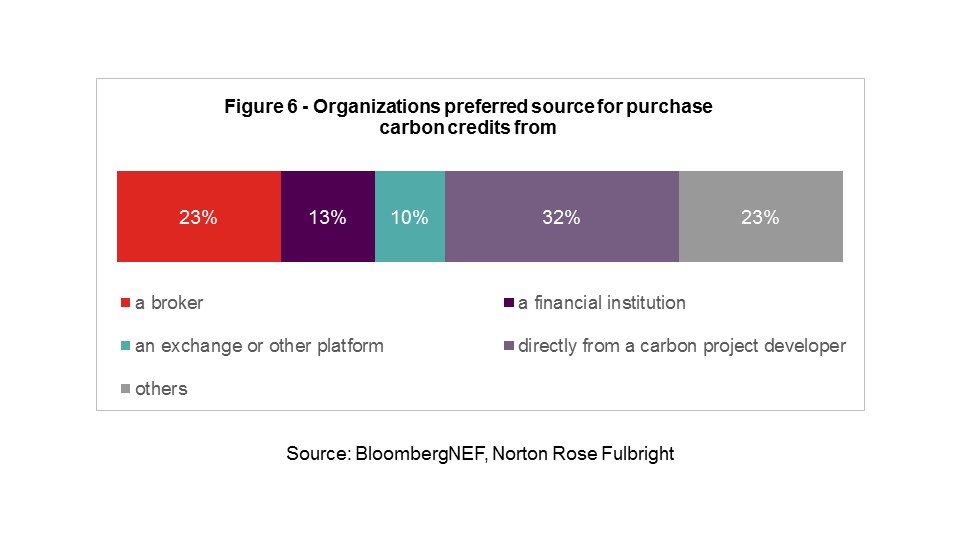

Respondents indicated a variety of preferences in terms of sourcing carbon credits, including purchasing directly from a carbon project developer, a broker, a financial institution and an exchange or other platform. However, the largest number of respondents indicated that their top preference was to purchase directly from a carbon project developer (Figure 6).

We consider that this is because many organizations perceive that they will receive better value if they negotiate directly with carbon project developers, rather than paying a premium to purchase carbon credits through an intermediary or over an exchange or other platform.

There are many benefits associated with purchasing carbon credits directly from project developers, for example having more insight into and in some cases control over the development of the project(s), and cost-effectiveness associated with removing the involvement of intermediaries.

While there are also risks associated with this approach (e.g. counterparty risk such as the project developer becoming insolvent, or project risks such as a reversal of sequestration), these can be addressed through appropriate protection in legal documentation.

Purchasing credits from a broker was the second most popular choice. Brokers do not typically take ownership of carbon credits, and instead facilitate the transaction for their clients.

Buyers can specify criteria, for example the amount of carbon credits they want to purchase, as well as the sectors and regions they want to buy in. This greatly reduces the complexity of purchasing carbon credits for a buyer relative to other options, although it can extend the timeline for buying them, compared with going through an exchange.

Contracting through a broker may be the most expensive route, as their business models often include an extra per-unit charge on each carbon credit purchased.

We note that only a tenth of companies prefer buying carbon credits through an exchange, despite this often being the fastest and perhaps least involved process. Our respondents may have higher-than-average experience in purchasing carbon credits, while respondents with less experience may prefer using exchanges.

We are seeing a significant increase in clients looking to establish carbon platforms that rely on blockchain technology

We are seeing a significant increase in clients looking to establish carbon platforms that rely on blockchain technology, and that will use blockchain to support carbon trading between users on the platform. We anticipate that interest in using blockchain to track the issuance, trading and retirement or cancellation of carbon credits will continue to grow.

Avoiding double counting and double claiming is critical

The foundational principle that emissions reductions cannot be double-counted is critical to the integrity of carbon markets. While this principle is widely accepted, new complexities have emerged as a result of the interaction of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and voluntary carbon markets.

Double counting includes:

- double issuance (i.e. more than one carbon credit is issued for the same emissions reduction);

- double use (i.e. a carbon credit is used twice); and

- double claiming (i.e. where the buyer and the seller both claim or count the same emission reduction towards their emissions reduction target).

The Article 6 rules agreed in Glasgow at COP26 fall short of attempting to regulate voluntary carbon markets, however they provided much needed clarity with regards to the process for authorizing mitigation outcomes for “other international mitigation purposes” and the application of corresponding adjustments.

Some purchasers of carbon credits on the voluntary market are likely to have a preference for carbon credits that have been authorized for international transfer and subject to a corresponding adjustment

Some purchasers of carbon credits on the voluntary market are likely to have a preference for carbon credits that have been authorized for international transfer and subject to a corresponding adjustment by the host country of the underlying project.

These processes have the effect that the emissions reductions represented by those carbon credits will not be counted towards the host country’s Nationally Determined Contribution, and avoid perceptions that the same emissions reductions have been claimed by both the host country and the entity retiring the carbon credits for voluntary offsetting purposes.

Verra and the Gold Standard are proposing to update their respective registries so that a label can be applied to carbon credits that have been subject to a corresponding adjustment.

The Gold Standard considers that carbon credits issued on the voluntary market must be subject to corresponding adjustments in order to be used for voluntary offsetting purposes. Otherwise, the user of the carbon credits can only claim to have financed the emissions reductions in the host country.

Verra has taken the view that it is does not require corresponding adjustments for voluntary offsetting purposes. Rather, each country will decide its own approach, and some countries may choose to apply corresponding adjustments in relation to carbon credits that are transferred internationally for voluntary offsetting purposes.

We consider that a two-tiered market may emerge over the next few years. It is likely that carbon credits that have been authorized for international transfer and subject to a corresponding adjustment will be considered to be higher quality than carbon credits that have not.

Privacy notice | Global law firm | Norton Rose Fulbright

Privacy Policy | BloombergNEF | Bloomberg Finance LP (bnef.com)

Norton Rose Fulbright and BloombergNEF