Global offshore wind: South Korea

Global | Publication | noviembre 2024

Information correct as of 26 November 2024.

In collaboration with:

Focus on: South Korea

Market overview

South Korea’s nascent offshore wind market has made strong advances in the last few years. The first commercial scale offshore wind farms have come online and several GWs of projects, both fixed and floating, are in various stages of development and construction.

The share of renewable energy in South Korea’s electricity generation mix reached 8.9 per cent in 2022, but the government plans to increase the share of renewables significantly.

On 31 May 2024 the General Committee on the Basic Plan on Electricity Supply and Demand released a working-level draft (Draft Plan) of the 11th Basic Plan on Electricity Supply and Demand (the 11th Basic Plan) that provides a blueprint for electricity demand and supply out to 2038. The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) expects to finalise the 11th Basic Plan by the end of 2024. The Draft Plan projects that renewable energy’s share of total energy generation will amount to 21.6 per cent by 2030 and 32.9 per cent by 2038.

MOTIE targets 14.3 GW of offshore wind by 2030 and 40.7 GW by 2038. MOTIE published a strategy paper in May 2024 which sets a government-led push to achieve a 6 GW annual increase in renewable energy. The strategy focuses on manufacturing, installation, financing and adapting the renewable energy market. It also provides for building the necessary infrastructure such as ports and ships and establishing a robust financial support system, with 1.2 trillion won allocated in 2024 and 9 trillion won by 2030. This strategy has evolved in the context of offshore wind when on 8 August 2024, MOTIE unveiled a roadmap to support the development of 7-8GW offshore wind in South Korea between the second half of 2024 until the end of the first half of 2026.

The Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) provides key support (replacing the previous FIT system in 2012) by requiring the country’s largest power generators (i.e. those with installed power generation capacity of over 500 MW) to progressively increase, on a yearly basis, the proportion of their power that is produced using renewable energy. Direct investment in a renewable generation asset is not the only way to meet RPS targets; generators can purchase renewable energy certificates (RECs) from renewable energy producers in order to satisfy their RPS obligations. The sale of these certificates creates revenue streams for renewable energy producers that complement the revenue received from the conventional sale of electricity.

South Korea: offshore wind projects

As at September 2024, there are a number of offshore wind projects with an electric business license, with a combined planned capacity of 28 GW. Based on publicly available sources, we have set out details of some of those projects.

| Project name | MW | Status | Ownership | |

| 1. | Gunsan Port |

3 | Operational |

KEPCO |

| 2. | Yeonggwang Yaksu |

4.3 | Operational |

Jeonnam Development Corporation (JNDC) |

| 3. | Woljeong |

5 | Operational |

Korea Institute of Energy Research (KIER) |

| 4. | Southwest Phase 1 |

60 |

Operational |

Korea Hydro and Nuclear Power Co., Ltd. (KHNP), Korea East-West Power Co., Ltd (EWP), Korea South East Power Co., Ltd (KOEN), Korea Southern Power Co. Ltd. (KOSPO), Korea Western Power Co Ltd (KOWEPO), Korea Midland Power (KOMIPO), Korea Offshore Wind (KOWP) and Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) |

| 5. | Yeonggwang Gun |

34.5 |

Operational |

EWP, Daehan Green Power and Unison |

| 6. | Tamra |

30 | Operational |

Doosan Enerbility Co., Ltd., NongHyup Bank, KOEN |

| 7. | Jeonnam 1, 2 and 3 |

897 |

Phase 1: 2022 auction award, in construction Phases 2 and 3: Development |

SK E&S and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners |

| 8. | Halim | 100 |

Construction |

KEPCO, Hyundai Engineering & Construction, KB Kookmin Bank, Baram Corp., KOMIPO |

| 9. | Sinan Government Project |

4,100 2,100 2,000 |

Development (in phases) |

KHNP, KOEN, KOMIPO, KOSPO, KOWEPO, KOWP, EWP, KEPCO |

| 10. | Ansan Pungdo |

200 | Development |

KOWEPO, Seohae Green Power and Wooram Construction |

| 11. | Anma | 532 | Development | JNDC, Korea Wind Corporation Co., Ltd., KHNP, Hyundai Engineering and Construction, Equis Development Pte. Ltd. |

| 12. | Gochang | 76.2 |

Development 2023 auction award |

Dongchon Wind Power, KOMIPO and Hyundai Engineering |

| 13. | Yeonggwang Nakwol |

364.8 |

Development 2023 auction award |

Myoungwoon Industrial Development and B.Grimm Power Public Co |

| 14. | Yeonggwang Chilsan | 151.2 | Development |

CW NR Co. Ltd |

| 15. | Yeonggwang Yawol | 108 | Development |

Daehan Green Power Corporation |

| 16. | Yeonggwang Hanbit |

375 | Development |

B.Grimm Power Public Co and local partner |

| 17. | Shinan Eoui |

99 | Development |

Shinan-Eoui Wind Co., Ltd. And B.Grimm Power Public Co |

| 18. | Abhae |

84.5 | Development |

Woori Green Energy Co LTD |

| 19. | Jeonnam Sinan |

300 | Development |

Posco Energy and KOSEP |

| 20. | Haewoori (floating) |

1,500 | Development |

Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners |

| 21. | Sinan UI | 396.8 |

Development 2023 auction award |

Hanwha Engineering & Construction, KOEN and SK D&D |

| 22. | Wando Geumil 1 and 2 |

600 |

Development 2023 auction award |

KOEN |

| 23. | Wando |

148.5 | Development |

KOEN |

| 24. | Cheongsapo | 40 |

Development |

G Wind Sky, Hanwha Investment and Securities and Corio Generation |

| 25. | Dadaepo | 60 |

Development |

Corio Generation |

| 26. | Gijang | 200 | Development |

Corio Generation |

| 27. | Ulsan | 136 | Development |

SK Ecoplant |

| 28. | Handong-Pyeongdae |

105 | Development |

Jeju Energy Corporation |

| 29. | Ulsan City |

6,100 | Development |

Ulsan City in collaboration with state-owned enterprises and commercial developers |

| 30. | South West |

2,700 |

Development |

KEPCO |

| 31. | Jindo (MyeongRyang, Manho and Jindo Baram) |

420 990 1,800 |

Development |

HD Hyundai Electric, Pacifico Energy Korea, CS Wind, Korea Ocean Engineering & Consultants and Daebul Shipbuilding |

| 32. | Seohae |

495 | Development |

RWE |

| 33. | Neulsaem Ui |

510 | Development | RWE |

| 34. | Hanee Baram |

2,000 | Development |

RWE |

| 35. | Incheon |

1,600 | Development |

Ørsted |

| 36. | Gray Whale (floating) |

1,500 | Development |

Corio Generation, TotalEnergies and SK Ecoplant |

| 37. | Maenggoldo |

600 | Development |

Corio Generation, TotalEnergies and SK Ecoplant |

| 38. | Geomundo |

500 | Development |

Corio Generation, TotalEnergies and SK Ecoplant |

| 39. | Bandibuli (floating) |

800 | Development |

Equinor |

| 40. | Donghae 1 (floating) |

200 | Development |

Equinor, Korea National Oil Corporation and EWP |

| 41. | Haesong |

1,000 | Development |

Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners |

| 42. | MunmuBaram (floating) |

1,125 | Development |

Hexicon and Shell |

| 43. | Jodo |

517 | Development |

B.Grimm Power Public Co and Goni Jodo Co., Ltd. |

| 44. | Yokjido 1 |

384 | Development |

KOMIPO and Vena Energy |

| 45. | Jindo | 855 |

Development |

Influx Inc. |

| 46. | Jindo | 3,200 |

Development |

Pacifico Energy |

| 47. | KF Wind (floating) |

1,125 |

Development |

Ocean Winds, Mainstream Renewable Power |

| 48. | Hanbandodado |

1,245 | Development |

Ocean Winds |

| 49. | Portfolio of 4 projects |

6,000 | Development |

Bp and Deep Wind Offshore |

| 50. | Dado |

900 | Development |

Northland Power |

| 51. | Bobae |

600 | Development |

Northland Power |

| 52. | Taean - Manipo Offshore Wind Farm |

504 | Development |

Vena Energy |

| 53. | West Sea Energy 1 |

1,500 | Development |

EDF Renewables |

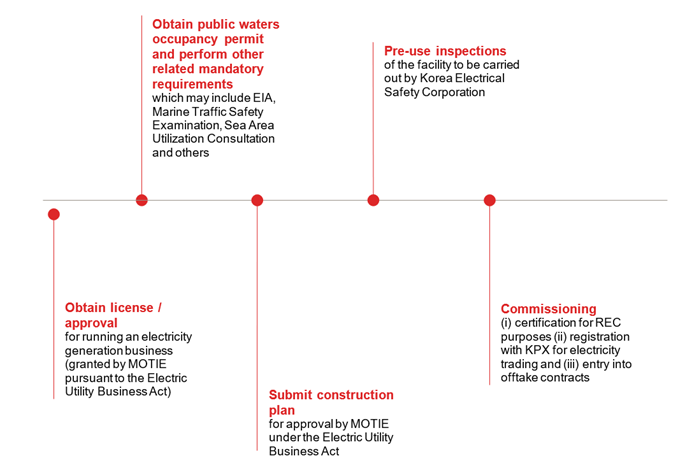

South Korea: development process overview

South Korea maintains an “open door” or developer-led approach to project development, with little active government support in the process.

However, we note that there were separate bills from each main political party submitted (Special Act on the Promotion of Wind Power Development and Distribution) which failed to pass in the 21st National Assembly (2020-2024). Similar bills are also pending in the 22nd National Assembly (2024-2028) and which, given the lack of controversy and similar intent, may be expected to eventually pass into law. If passed, the Acts will create a ‘one-stop-shop’ system which will provide for relevant Governmental Authorities to pre-clear social acceptability (e.g., stakeholder consent) requirements and designate pre-determined areas for offshore wind farm project development.

Typical steps that the developer is required to complete in the development process include:

- Identifying a site (South Korea does not publish predetermined areas for offshore development)

- Feasibility studies, including data collection, sub-sea surveys, maritime traffic safety assessment (MTSA), environmental impact assessment (EIA) and grid connection

- Application for an electricity business licence

- Permitting and application for grid connection

- Public consultations and compensation of affected stakeholders (e.g. fishing & marine shipping industries)

- Contracting, financing and construction

South Korea: auctions

In 2022 the New & Renewable Energy Center (NREC) of the Korea Energy Agency (KEA) amended the Rules on the Issuance of Supply Certificates and Operation of the Trading Market (the REC Rules) to launch an auction system for wind power projects. The awards entitle the winning bidders to a 20-year fixed price offtake contract for RECs (a REC Contract). The revenue for an operational project that has been awarded capacity in the auction, as recorded in a REC Contract, is the sum of the system marginal price (SMP) received through the sale of the electricity through the Korea Power Exchange (KPX) and the fixed price for the REC awarded through the auction (please refer to the “South Korea support regime” section below for more details regarding the SMP and REC valuation and weighting).

The first auction was announced in September 2022 with a ceiling price of $0.13/kWh. One offshore project was awarded capacity in this round; the 99 MW Jeonnam 1 developed by Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and SK E&S.

The 2023 bid round focused on bid prices, with the ceiling price kept confidential. Bidders were required to have completed their EIAs before submitting bids. Five projects with a total capacity of 1,431 MW were awarded capacity in December 2023. The winning bidders were:

| Project | MW | Ownership |

| Yeonggwang Nakwol |

364.8 |

Myoungwoon Industrial Development and B.Grimm Power Public Co |

| Wando Geumil 1 and 2 |

600 |

KOEN |

| Shinan Ui |

396 | KOEN, Hanwha and SK D&D |

| Gochang |

76.2 | Dongchon Wind Power, KOMIPO and Hyundai Engineering |

On 8 August 2024, MOTIE announced a roadmap for future offshore wind auctions. The first auction round for offshore wind capacity under the reformed auction roadmap opened on 25 October 2024, with applications closing on 22 November 2024, for 1.5GW of offshore wind capacity. From 2025, the auction cycle has been changed to occur in the second quarter of each year. If capacity targets are not reached in the second quarter auction, an additional auction will be conducted in the fourth quarter. From the second half of 2024 to the first half of 2026, a total of 7GW to 8GW is available for bidding through three separate auctions. These auctions are expected to offer the following capacity:

| Project type |

2024 H2 (announced) | 2025 H1 (anticipated) |

2026 H1 (anticipated) |

| Fixed | 1,000 MW |

2,000 – 2,500 MW |

1,000 – 1,500 MW |

| Floating | 500 MW |

500 – 1,000 MW |

1,000 – 1,500 MW |

In addition, a public-led capacity auction is expected to be introduced for the 2025 auction rounds.

The auctions all include a two-stage evaluation process. Phase 1 will involve an assessment of the non-price factors and the NREC’s Wind Power Auction Committee will select projects representing 120 to 150 per cent of the targeted capacity to proceed to phase 2. Phase 2 will be based on price. The bidder with the highest combined score will be successful in the auction. The ceiling price for the 2024 H2 auction applicable to offshore wind projects (including floating wind) was capped at KRW 176,565/MWh.

While South Korea does not directly mandate local content, the bid evaluation criteria results in a 50-50 weighting between price and non-price factors, which include industrial economic effects (including consideration of safety and the public and contributions to the local supply chain), community acceptance and maintenance of the facilities.

In response to industry feedback, the offshore wind roadmap also provided for the extension of the deadline for completion of the offshore wind farm project following entry into the REC Contract. The revised deadlines are as follows:

| Offshore wind farm capacity | COD Deadline |

| 100 MW or less |

54 to 60 months |

| 100MW – 300MW |

60 to 72 months |

| 300MW + |

60 to 78 months |

It has also been confirmed that force majeure and grid delays (attributable to KEPCO) can be relied upon by projects to obtain further extensions to the COD Deadlines set out above.

South Korea: support regime

1 Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS)

| 2022 | 12.5% |

| 2023 | 14.5% |

| 2024 | 17% |

| 2025 | 20.5% |

| 2026 | 25% |

The power generating companies can meet RPS targets by directly investing in the installation of renewable energy generating capacity or through the purchase of RECs (see below). If a company fails to meet its RPS targets, it will be liable to pay a penalty in an amount up to 150 per cent of the average REC price for its REC shortfall. Penalties vary depending on the nature of non-compliance (as well as the frequency).

Further reforms to the RPS are anticipated to be enacted in 2025.

2 Renewable Energy Certificate (REC)

One REC documents that 1 MWh has been generated by a certified eligible facility, however, different multipliers (i.e. weightings) are then applied to the output depending on a number of factors including the type of renewable energy used to produce that output. Offshore wind has a high weighting value compared to e.g. solar PV or onshore wind, demonstrating the government’s focus on this market. The NREC of the KEA has authority to issue RECs to certified eligible facilities. NREC will determine (upon inspection) whether a facility complies with the standards for the applicable renewable energy (upon application by the relevant renewable energy producer) and can therefore be certified and registered. Once this has occurred, the certified eligible facility is able to receive RECs and partake in the scheme. RECs can be traded on the spot market or under long term contracts (such as the REC Contracts). In a recent positive development, whereas previously the value of the REC multiplier would be determined at the time of certification, it has now been confirmed that in relation to the 25 October 2024 auction, the REC multipliers that are submitted at bid stage will apply following certification.

3 REC weighting

The weighting values for RECs relating to offshore wind take into account the straight-line distance between the coastline and the central position of the nearest turbine to the coastline and the water depth where the turbine is located. Weightings for offshore wind may potentially reach a maximum of 4.9.

Whilst NREC can provide a forecast of the expected REC weights in advance, the final weighting is determined only upon completion of construction and confirmation of REC issuance.

The Guidelines on the Management and Operation of New and Renewable Energy Mandatory Supply and Mandatory Fuel Mix System prescribe a review of the REC weighting every three years.

The REC weighting will be reviewed in the second half of 2024.

4 System Marginal Price (SMP)

5 Corporate PPAs (CPPAs)

CPPAs offer an alternate route to market for generators. Direct wire PPAs, retail / sleeved PPAs and virtual PPAs are permitted in South Korea.

On January 5, 2021, MOTIE announced the introduction of a Korean RE100 system and a revision to the Enforcement Decree of the Electric Utility Act. Under the RE100 campaign, corporates commit to transition to 100 per cent renewable electricity consumption by 2050.

On March 24, 2021, Korea’s National Assembly passed an amendment to the Electric Utility Act that will enable companies to enter into PPAs for electricity generated from renewable energy projects.

The Electric Utility Act amendments allow renewable energy generators to sell electricity directly to end-users without having to go through the Korean Power Exchange.

Electricity consumers who may utilise a CPPA are either general power or industrial power consumers of at least 300kW.

Although power sold under a CPPA will not be eligible for issuance of RECs, the same agency that issues RECs (the Korea Energy Agency) issues “renewable energy use certificates” with respect to such power. These use certificates will include the information currently included in RECs to enable easy tracking of the environmental attribute and to prevent double-counting for purposes of compliance with corporate sustainability goals such as the RE100 initiative.

In light of this, we anticipate the nascent trend towards blended offtake structures in other markets also emerging in South Korea. Click here to find out more about the implementation of these structures.

South Korea: obstacles and challenges

Currently the offshore wind sector in South Korea is facing a variety of challenges ranging from those that are typical of a new industry in a new market, through to challenges conforming traditional Korean regulatory and project financing practices to incorporate international best practice to better facilitate offshore wind project development:

|

“First-in-country” and technology risk The nascency of the offshore wind sector in South Korea and the significant ambition for floating offshore wind means that South Korea has many “firsts” to traverse in the evolution of its domestic offshore wind industry. The coming years will be key for developing the skill and expertise necessary to deliver offshore projects of this type and size, particularly given the need to facilitate floating offshore wind projects to meet South Korea’s policy targets. To find out more about the unique challenges inherent in the development of floating offshore wind projects, please click here. |

Wind conditions Unlike Europe, some of South Korea’s coastal areas are typhoon-prone.This creates obvious difficulties for the manufacture and design of turbines. Contractors and research institutes are partnering to develop solutions (e.g. the research project between Doosan Heavy Industries & Construction and the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning). |

|

Supply chain and procurement South Korea generally has high-quality infrastructure, but is lacking the required scale of specialist equipment needed for offshore wind projects and more particularly, to support the development of floating offshore wind projects. Installation vessels will need to be built or imported whilst harbour facilities and local manufacturing processes will need to be modified and/or upgraded. These supply chain challenges might be exacerbated given the South Korean REC auction bid evaluation criteria incentivizes local content / component sourcing as well as community benefit and national security. More generally, South Korea is not immune from the supply chain constraints affecting the global offshore wind industry. Among the topics to consider in this context is the anticipated involvement of Chinese Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs). This remains a vexed industrial policy question; however, many developers are considering using Chinese OEMs having regard to the potentially significant cost benefits of doing so. |

Permitting Whilst this is not unusual in the region, developers in South Korea are subject to a complex permitting process, which requires coordination across several government authorities. Examples include separate approval procedures administered by a variety of central government ministries including the Ministry of Trade Industry and Energy (MOTIE), Korea Electric Power Corp. (KEPCO), Ministry of Environment (MOE), Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF) and Ministry of Defense (MOD), as well as local government, in order to obtain critical approvals ranging from the electricity business license, grid interconnection agreement, environmental impact assessment, maritime traffic safety assessment, and defense facilities impact operability review & radar impact assessment (RIA). These complexities are exacerbated by the fact the impetus for initiating many of these approval processes is imposed on the developer, and to date the South Korean government has taken a hands-off approach to facilitating stakeholder consents (see below). Legislation remains under consideration to simplify the licencing procedures. |

|

Local community interests The Government has been keen to promote community involvement in new renewables projects. In addition to maritime spacial planning (MSP) and related maritime traffic safety concerns raised by the marine shipping industry, the commercial fishing industry is often vocal in its opposition to proposed developments due to possible negative effects wind farms may have on marine life and catch rates. Both issues can lead to lengthy negotiations, delayed government approvals and rising costs. The Government intends to establish a consultative body made up of business entities, central and local government to manage and facilitate stakeholder consents (including fisheries) in a more efficient manner. To date we understand that one such integrated body has been established. The government’s one-stop-shop legislation is intended to go further by facilitating the establishment of pre-approved development sites to reduce delays resulting from the need for developers to obtain stakeholder consents. |

Grid connection Like many other grids around the world, the Korean grid has faced increasing pressure in recent years, with many projects struggling to obtain firm, timely and uncurtailed grid connection arrangements for their projects. It is pertinent to note that South Korea has curtailment points at both the transmission and distribution levels. Consideration will need to be given to the anticipated timing for connection, and whether a flexible or firm connection is being provided. Unless a direct wire PPA (or similar alternative offtake arrangement is pursued), developers must enter into a grid connection agreement with KEPCO, who holds the exclusive rights to the transmission, distribution and sale of electricity in South Korea. Renewable projects are not given priority for grid connection and there is potential for delay if several offshore projects seek connection concurrently. As we commonly find internationally, there is little (if any) scope for negotiation of the connection agreement, which has been found to contain certain bankability challenges. It is also pertinent to note that the offshore wind project is responsible for building out the offshore substation and export cables up to the onshore substation connection point. |

|

Financing market South Korea has a liquid, capital cost competitive and mature domestic project finance market. While this in many respects bodes as an advantage for the development of the South Korean offshore wind sector, the role for international lenders and advisers is likely to remain important for a number of reasons. The international offshore wind financing market exhibits a number of unique structural features that we expect to also become features of the finance packages in the South Korean offshore wind market. For example, South Korean lenders will need to get comfortable with truly non-recourse financing structures as well as with the impact of multi-contracting procurement structures without the protection of completion guarantees and financing cost support. There are also a number of South Korean market specific factors that will also need to be considered from a financing perspective, including the impact of the Resident Participation Scheme, which can be used to improve the debt capacity of a project. The role of multilaterals (including ECAs) is also a topic to follow closely, including vis-à-vis the participation of South Korean multilaterals in the financings of domestic offshore wind farm financings. |

REC weighting and REC auction design While the auction roadmap released on 8 August 2024, and confirmed upon the announcement of the auction on 25 October 2024, represents a positive step forward from a policy perspective as MOTIE has addressed a number of industry concerns therein, it remains to be seen whether these adjustments will facilitate the expeditious development of offshore wind farm capacity in South Korea. While disclosure of the ceiling price applicable to offshore wind projects in the H2 2024 REC auction is likely to be viewed as a positive development, we note that the proposed ceiling price is the same for both fixed-bottom and floating offshore wind farm projects. It remains to be seen whether this will negatively affect the commerciality of the floating offshore wind projects bidding given the significant cost differences between the two technologies. This means that the REC weighting (which takes into account distance from shore and water depth) will be the primary tool for providing additional support to floating offshore wind projects vis-à-vis their fixed-bottom cousins. The [impending] changes to the REC weighting methodology will also be interesting to consider in this respect, given there are a myriad of factors that go beyond distance from shore and water depth that disproportionately affect the development of floating offshore wind projects (such as the heightened costs of addressing maritime safety related considerations). |

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025