Publication

ESG and internal investigations: New compliance challenges

As ESG concerns have come to the forefront in different jurisdictions, the scope of these inquiries is expanding in kind.

Uncertainty has gripped 2020 with financial pressures being felt by a wide range of businesses. Borrowers are seeking to restructure their debt to ensure they have the liquidity to ride out the economic downturn and lenders keen to assist their clients (or make new investments) are considering the options realistically available.

Tax is a critical component in the decision-making process, with jurisdiction-specific tax consequences to be taken into account on any cross-border debt restructuring.

For both borrowers and lenders, there are tax-related pitfalls and also opportunities that might arise in international debt restructurings, which must be at the forefront of any restructuring.

Three commonly considered debt restructuring scenarios are debt-to-equity swap; sales of distressed debt, and debt waivers (whether full, partial or conditional). The fact that the tax treatment varies according to the rules of each jurisdiction emphasises the need for careful consideration of the tax consequences in any proposed restructuring. This article flags some of the trends and idiosyncrasies that lenders and borrowers need to be aware of in order to avoid pitfalls and importantly take advantage of favourable rules.

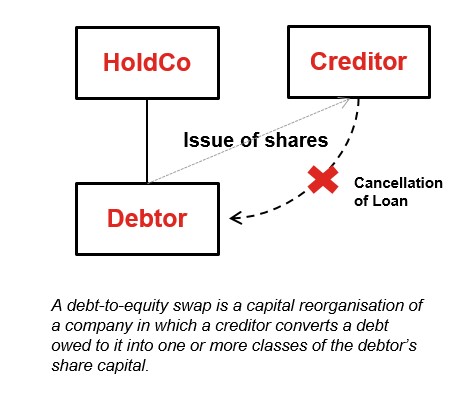

A debt-to-equity swap, substitution or restructuring is a capital reorganisation of a company in which a lender (usually a bank, possibly together with other banks, bondholders or creditors) converts indebtedness owed to it by a company into one or more classes of that company’s share capital.

From a lender’s perspective, a debt-to-equity swap should generally be a tax neutral transaction, with the tax book value of the shares received equal to the tax book value of the converted debt. Having said that, where the lender is a related party of the borrower the treatment may be different. A number of jurisdictions such as the Netherlands have legislation that prevents a lender from depreciating a debt and subsequently converting the debt into equity in a tax neutral way.

The borrower may suffer a reduction in its tax losses (which can be used to reduce future income) or be treated as receiving an amount of taxable income if the value of the equity is less than the value of debt released. In some jurisdictions though such as the UK and France a debt-for-equity swap may be treated as tax neutral. Achieving this tax neutral result may require particular formalities to be complied with. In the UK, for example, the relief is only available if the shares being issued are ordinary share capital – care must be taken to ensure that this is the case.

There are also jurisdictions where debt-for-equity swaps are actually adversely taxed. In Germany where a borrower is relieved from their debt, the cancellation will trigger a taxable gain to the extent the debt was impaired - it is for this reason debt-for-equity swaps are not commonly seen in Germany.

If there is a change of control of the borrower arising from the debt-for-equity swap, this may lead to further tax considerations, for example, restrictions of carry forward losses or degrouping charges. There will also be a change in the tax profile for the parties going forward—interest paid on a debt will likely be taxed differently to any dividends while the treatment of the parties on any future exit would again likely be different.

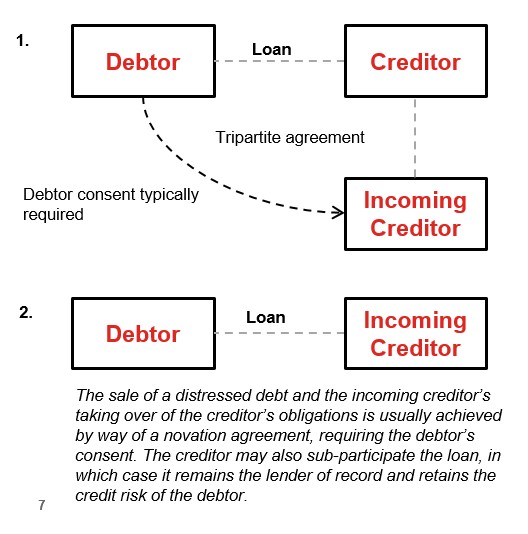

The sale of distressed debt is a mechanism for a lender to reduce their balance sheet exposure to debts which may currently be non-performing or have a significant risk of future default. In such circumstances, the debt would be expected to be sold at a discount to face value in view of the distressed financial circumstances of the borrower.

The common response to the question of whether the borrower should suffer any tax consequences as a result of the sale of distressed debt to a new lender is understandably ‘no’.

But this is not, however, always the case. In France, the general rule that the borrower will not suffer any tax implications upon the sale holds true only if the borrower is notified of the change in lender. This underlines the importance of ensuring that tax matters are considered to ensure that the necessary formalities are carried out on any restructuring, even where one would reasonably not expect any impact on the borrower.

The situation may also be complicated where the parties are connected, for example, where a borrower wants to acquire a debt into a group to remove the controls placed on it by third party lenders. In Canada if a debt is sold to a connected party of the borrower for less than 80 per cent of the principal amount of the loan, then a taxable event may arise. Similar rules also exist in the UK (albeit with carve-outs including where the debt is released shortly after the sale) and the US.

The selling lender will expect to realise a tax deductible loss on any discount to the carrying value. Where the buyer and seller are connected parties or the transaction is otherwise than at an arm’s length, tax loss restrictions may apply.

From the perspective of the buying lender, the base cost in the debt will usually be the price it paid (assuming again that the acquisition is on arm’s length terms). In Luxembourg though where the sale is set up to be on beneficial terms for the incoming lender then they may be treated as having received a hidden distribution.

The buying lender will also need to consider transfer taxes which may apply particularly if the loan is equity-like in nature (for example, because it carries results-dependent interest) and the withholding tax position and whether any structuring is needed to mitigate any such tax.

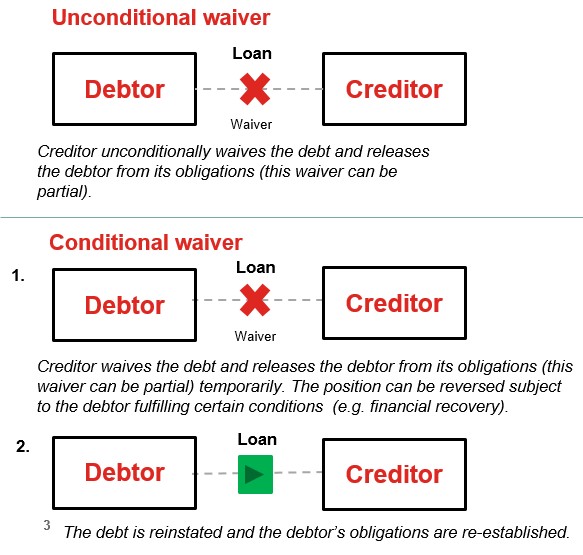

A debt waiver, debt modification or debt cancellation relieves, either temporarily or permanently, the borrower of its financial obligations under a debt instrument. It is a common element in restructuring scenarios including UK Schemes of Arrangement and US Chapter 11 plans (and is expected to a part of new WHOA legislation in the Netherlands).

The diagram below sets out two distinct iterations of the solution, being the conditional waiver and the unconditional waiver.

The starting point for a standard unconditional debt waiver is that borrowers can expect to be subject to tax on the value of the waived debt while lenders can expect to realise a corresponding tax benefit. A number of jurisdictions including the UK, Germany and US provide borrowers with relief in distressed situations. Furthermore, Canada and Australia have debt forgiveness rules which rather than imposing an immediate tax charge require the borrower to reduce its tax attributes by the amount of the waiver.

For connected parties, the situation may be tax neutral in some jurisdictions (for example, the UK, the Netherlands, South Africa) while in others (such as France, Germany and Luxembourg) there may still be tax liability.

Compared to unconditional waivers, conditional waivers (where the debt is reinstated at some future point) are not as commonly encountered. Indeed many jurisdictions would treat them as an amendment to the terms of the loan as opposed to a waiver. Accordingly many of the jurisdictions surveyed do not have specific taxing provisions dealing with conditional waivers. Germany though does see them used and while the waiver triggers taxable income for the borrower when the debt is reinstated there is a corresponding loss with the lender’s position similarly reversed out. The borrower’s loss on reinstatement means that in Germany the mechanism can be used to refresh losses in a change of control situation.

When the terms of a loan are amended, it is necessary to consider whether this gives rise to a new loan such that new treaty formalities need to be undertaken from a withholding tax perspective.

Whilst there are many general principles that apply to the tax treatment of debt restructuring solutions across the jurisdictions, minor nuances and major deviations can be found, which should be at the forefront when considering the options available. Complex restructuring solutions generally have complex tax implications – it is without doubt a critical component.

Publication

As ESG concerns have come to the forefront in different jurisdictions, the scope of these inquiries is expanding in kind.

Publication

The “First Ready, First Connected” reforms proposed by the Electricity System Operator (ESO), and which could be in place by the end of Q2 2025, aim to address existing issues with the application process for connections to the GB electricity grid.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025