On 21 September 2023, the

European Chips Act will enter into force. Similarly to recent legislation in the United States and Japan, and a near-final legislative proposal in Taiwan, the Chips Act is intended to incentivize production of semiconductors in the EU and ensure security of supply. It has three pillars.

Pillar 1: The Chips for Europe initiative, including the Chips Fund

The Chips for Europe Initiative is intended to promote the conversion of research and development into demand-oriented, application-driven, secure and energy efficient semiconductor technologies, focusing on:

- Building up advanced design capabilities for integrated semiconductor technologies

- Enhancing existing, and developing new, pilot lines (with testing and experimentation facilities) in the EU to enable development and deployment of cutting-edge and next generation semiconductor technologies;

- Building advanced technology and engineering capacity for development of cutting-edge quantum chips and associated semiconductor technologies;

- Creating a network of Competence Centres by enhancing existing or creating new facilities; and

- Facilitating access to debt financing and equity, particularly for start-ups, scale-ups, SMEs and small mid-caps in the semiconductor value chain, through a blending facility under the InvestEU Fund and via the European Innovation Council (the “Chips Fund”).

The Chips Act sets out specific goals under each of these objectives.

In addition, the Chips Act creates a framework for combining funding from EU Member States, the EU budget and private investment. It will also create the option to create a European Chips Infrastructure Consortium, a new public-private sector consortium in which Member States and private legal entities participate to jointly apply for specific actions to be funded by the Chips for Europe Initiative.

The Chips Fund is intended to improve the leveraging of EU funding and support companies having difficulty accessing finance. It is also intended to accelerate investment in semiconductor manufacturing technologies and chip design and improve security of supply for the semiconductor value chain. The EU will contribute € 4.175bn from the Horizon Europe and Digital Europe Programmes to the Chips Fund, wants the Member States to match this (subject to compliance with State aid rules), and hopes to mobilise another € 43bn of private investments.

Only entities established in the European Economic Area (i.e., EU Member States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway) are eligible for funds under the Digital Europe Programme. However, entities established in the EU Member States and Albania, Armenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Faroe Islands, Georgia, Iceland, Israel, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Norway, Serbia, Tunisia, Turkey and Ukraine are automatically eligible under the Horizon Europe Programme. Entities from Australia, Brazil, Canada, India, Japan, Mexico, and New Zealand can participate in the Horizon Europe Programme (although they are not automatically eligible for funding).

Most of the Chips Fund funds will be channeled through the Chips Joint Undertaking (CJU), whose membership will include the current Key Digital Technologies Joint Undertaking (KDTJU) members (i.e., the Commission, EEA Member States and three industry associations (AENEAS Association, INSIDE and EPoSS)). The CJU members that are public authorities will select the projects to be funded, taking into account capacity building and research and innovation. As the Chips Act makes clear, whether a technology is “innovative” does not turn only on whether the development relates to smaller node technologies, other factors are also relevant. Funding will be awarded through transparent tenders.

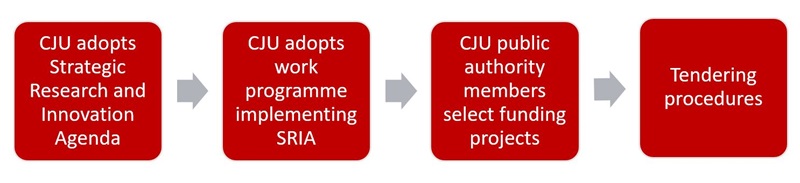

Which programs will be launched and selected will depend on the CJU’s priorities. Following the entry into force of the Chips Act and related legal texts, the CJU will develop and adopt a strategic research and innovation agenda that will guide the CJU’s work for the coming years. The agenda will be implemented through work programs, on which basis the CJU will select funding projects. It is expected that the CJU will start its work on the strategic research and innovation agenda as a matter of urgency.

The Chips Act adopts an open approach to calls for proposals under the Chips for Europe Initiative, which means that funding will be open to individual companies as well as to different legal forms of cooperation, including, for example, multi-national consortia, joint ventures, public-private partnerships and partnerships between corporations and academia. In addition, it creates a new consortia structure: the “European Chips Infrastructure Consortia” (ECIC). An ECIC must involve at least three public or private legal entities from three different Member States. It can also have Member States as members. The ECIC concept was created to bring together EU, Member State and private funding. Where the CJU restricts participation in projects to multi-national consortia, the ECIC may be an attractive form of cooperation for private entities from different EU Member States.

Complaints regarding decisions by the CJU can be made to the European Ombudsman, and actions for annulment can be brought before the General Court of the EU (if applicants that are not addressees of a CJU decision can show direct and individual concern, such that they have standing).

Pillars 2 and 3: Integrated Production Facility and Open EU Foundry designation will mean easier access to permits and fast-tracking of procedures but will impose obligations during supply crises.

To ensure security of supply and the resilience of the semiconductor ecosystem, the second pillar of the Chips Act introduces the potential for designation as Integrated Production Facilities (IPFs) and Open EU Foundries (OEFs) - manufacturing facilities providing semiconductor manufacturing capabilities that are “first-of-a-kind” in the EU and contribute to security of supply and a resilient ecosystem in the internal market. To be an IPF or OEF, a facility should have a clear positive impact, with effects beyond the undertaking or the Member State concerned, on the EU semiconductor value chain. While IPFs are vertically integrated, OEFs offer a significant degree of their production capacity to others (e.g., fabless semiconductor companies).

Any undertaking or consortium may file for recognition as an IPF or OEF. The Commission, in consultation with the European Semiconductor Board, will consider such applications. Once recognised as an IPF or OEF, an undertaking or consortium may, without prejudice to State aid rules, receive support from Member States. In addition tofunding, this support can include fast-tracking of administrative application procedures in relation to planning, construction, and operation.

While designation as an IPF or OEF can represent an opportunity, it also comes with potential obligations in the event of a shortage of supply: the third pillar of the Chips Act sets up a monitoring and crisis response mechanism. The Commission can use this mechanism if serious disruptions to supply of semiconductors lead to significant shortages that have a negative effect on one or more important EU industry sectors. The Commission can implement emergency measures that include:

- Requiring IPFs and OEFs to accept and prioritise the production of crisis-relevant products for critical sectors.

- Requiring other semiconductor undertakings to similarly prioritise such crisis-relevant products if they have agreed to do so in connection with receiving public support.

- Imposing periodic penalty payments of up to 1.5% of average current daily turnover for each working day of non-compliance with an obligation to prioritise orders. The Court of Justice of the EU has unlimited jurisdiction to review such decisions.

The EU Chips Act initiative should be viewed in the context of similar initiatives worldwide

The EU adopted the Chips Act in response to a worldwide shortage of semiconductors. Other large economies, including the United States, Japan, Taiwan, China and South Korea have set up, or are in the process of setting up, their own schemes to incentivise increased domestic production of chips. Many of these schemes involve subsidies. For example, the United States has committed US$52bn to its semiconductor supply chain. Because the number of different frameworks risks creating a subsidy race, the Commission has called for full transparency of state subsidies offered to stimulate production of chips.

Beyond such transparency, the Commission can review the competitive effect on EU markets of benefits received from ex-EU states that have an effect in the EU (under the Foreign Subsidies Regulation).