Introduction

The global spotlight is on Australia. It has intensified with the election of a new Federal Government last week.

Australia has one of the largest interconnected electricity systems in the world, traversing approximately 5,000km longitudinally. A decade ago, Australia had minimal renewable generation. Now, as much as 57% of all the electricity used in the National Electricity Market (NEM) at certain times comes from renewable generation. Predictions are that the NEM will be devoid of coal-fired generation by 2040.

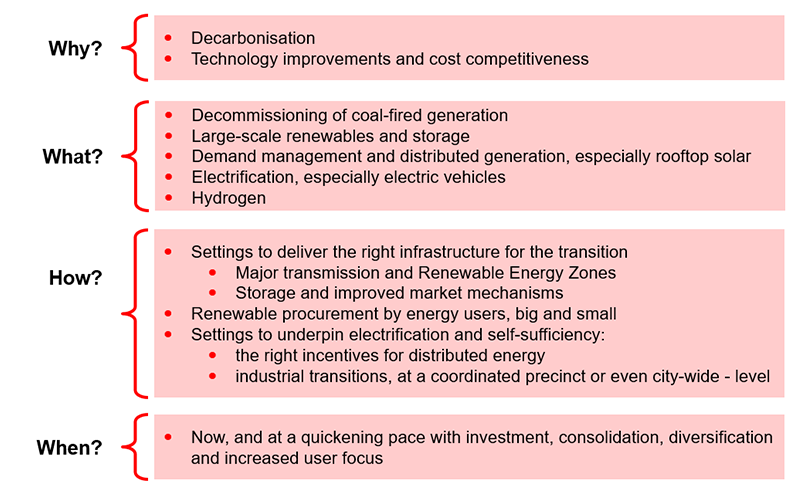

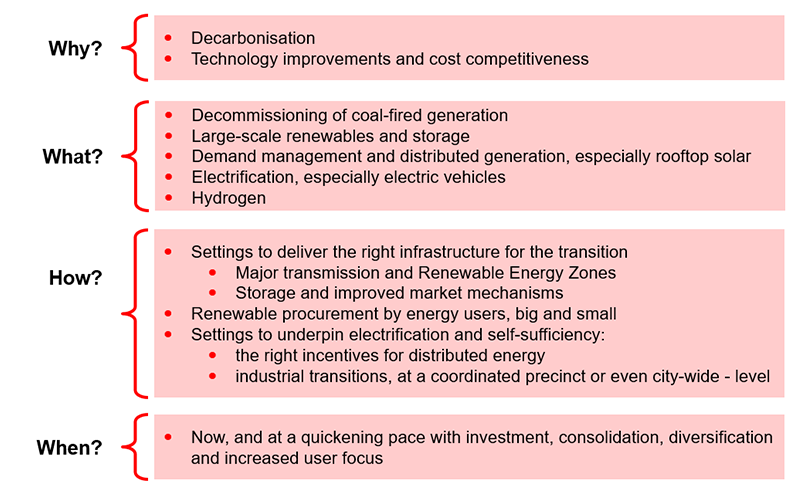

Rapid retirements of thermal generation, major renewables growth, electrification and unprecedented investment in technology and infrastructure (both private and public) are leading to an accelerating power system transition. Our article identifies why, how and the opportunities that it presents right now.

The focus of this article is on the NEM. However, very similar themes arise Australia-wide. A short explanation of the NEM appears at the annexure to this article.

The trade-off between decarbonisation and economics

The legacy of Australia’s carbon-intensive resources sector impacts the historical structure of the NEM and the relativity of input costs for different generation technologies. It therefore impacts the economics of the transition to renewables.

The prominence of coal, oil and gas production in the Australian economy also creates significant inertia against change at a macro policy level.

Nonetheless, with abundant renewable resources (sun, wind and hydro) in Australia and a growing focus upon decarbonisation, there has been a thriving renewables development industry here for many years. Some pioneers have faced significant headwinds. Grid stability and congestion have jeopardised some renewables developments, so too have construction and procurement delays, contractor insolvencies and regulatory hurdles.

Now though, the industry is moving into a more mature phase thanks to the early adopters. The following factors are contributing to this:

- authorities, regulators, networks and offtakers are accustomed to the nature of these projects;

- the cost of renewable technology has fallen dramatically;

- procurement of electricity from renewable sources is becoming mainstream; and

- there has been a change in approach, structure and settings (as noted later in this article).

A stepping stone to the inevitable

The emergence of a sophisticated renewables infrastructure industry has created a platform for the private and public sectors to visualize and plan for the power system of the future.

It is well-accepted that thermal generation has a limited lifetime in the NEM. Various industry experts, including AEMO have commented on the following.

- Coal (and gas) generation is being made unavailable by its owners, and retirement plans are being brought closer.

This is being driven by a combination of factors, including the fact that renewable generation is proving to be cost competitive to traditional baseload, meaning baseload is no longer so regularly dispatched. Moreover, some of the owners of the major power stations have taken the view that where their economic pay-off is borderline, the ongoing operation of these plants is not consistent with the environmental conscience of the public or its shareholders and so have made the decision to shut early.

AEMO’s draft Integrated System Plan (ISP) indicates that the recent announcements by thermal plant owners to retire (such as Origin Energy’s Eraring and Energy Australia’s Yallourn) suggest that about 5GW of the current 23GW of coal plant capacity will leave the market by 2030.

- Coal generation is becoming less reliable.

With ageing fleets comes the prospect of major and longstanding outages. We have seen a number of high profile outages occur, with reliability of plants at the lowest level seen for a long time.

There has been a very high penetration of wind and solar projects across Australia in recent years and at particular times of day. For example, in the fourth quarter of 2021, NEM instantaneous renewable share of total generation reached a record 61.8%, with wind and grid-scale solar accounting for 28% combined. Amplified by the anticipated deficit in supply from the exit of coal, the case for renewables has become more robust.

Interestingly, the most significant single contribution to the changing generation mix is that of rooftop solar. AEMO predicts that these systems alone could supply up to 77% of total electricity demand at times by 2026.5

Looking to the future, the potential for major increases in electricity demand will combat the “death spiral” fears that emerged last decade in connection with grids becoming underutilised due to the amount of localised rooftop and other technologies.

Now it is expected that distributed generation and smarter grids will complement swells in local load, coming from the electrification of industry as it shifts away from oil and gas. Electric vehicles alone have the potential to increase electricity demand fundamentally. There is a body of work being undertaken to make this more efficient at the distribution level.

At the large scale, grid-connected hydrogen projects will also contribute to increased demand. The profound opportunity for, and trajectory of, major hydrogen projects in Australia will be the subject of a separate publication shortly.

This all signals that we need lots of generation to be built, but in the right way.

A zig-zag transition

Of course, Australia is experiencing the quintessential challenge of transitioning effectively from traditional baseload dispatchable sources to intermittency.

As renewable resources become the NEM’s mainstay, the challenge will be to preserve the stability and resilience of the system. AEMO’s draft ISP notes that firming and some gas-fired generation, potentially fuelled by hydrogen, to be important as coal generation retires. This will help manage periods of low renewable energy output and to provide power system services to provide grid security and stability.

There will need to be enough renewables in the system before coal plant retirements can occur. This will lead to a “zig-zag” pattern of installed capacity (and wholesale prices) in the NEM as new tranches of generation are connected, before large portions of capacity are retired over time.

So, a short summary of how to solve a very complex problem is that the transition requires ensuring that:

- there is the right mix of wind, solar and hydro - and lots of it to front run planned (and potentially some unplanned) retirements and demand growth; and

- when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing, that renewable generation is able to be dispatched.

This necessitates large scale storage so that electricity can be utilised when it is needed - not just when it is generated. It also necessitates improved transmission infrastructure and regulatory frameworks that facilitate the right engineering solutions and aids participation of new technologies to their full potential.

Major transmission

With so much renewable generation needed so soon, there is significant need for large-scale new transmission builds and upgrades to existing transmission infrastructure.

Improved transmission infrastructure is not just about more and higher capacity poles and wires, but also technology to support the different generation mix now plugging in. This may include storage, synchronous condensers and other technologies that enable the grid to function more robustly. These technologies, if sized and put in the right place, can also reduce the need to otherwise oversize transmission systems.

Transmission upgrades were once the exclusive domain of the regulated transmission networks. Those network businesses must undertake lengthy efficiency investment studies and consultations before commencing major projects. Add to this the profound upfront finance and resources required even on a single project and the fact that the networks still have to provide service throughout their State 24/7, including through bushfires and floods – and we have a bottleneck.

This has seen the rise in the deployment of private transmission for smaller scale projects and small renewable “hubs”, made possible by changes in the regulatory framework.

We now also are seeing the deployment of major transmission infrastructure, such as Renewable Energy Zones (REZs), through partnerships between the private sector and Government. These are seen as a proactive way to achieve a curated infrastructure solution that is better located, and delivered sooner.

Settings needed

Implementation of the settings needed to optimise the transition are underway. We expect to see a combination of policies and direct government funding necessary to facilitate and incentivise the right kind of private investment and ensure that the lights stay on.

Industry will also be assisted by a clear and consistent message across Governments as to the need and pathway for that transition.

As of 23 May 2022, Australia has a new Federal Government. The Australian Labor Party (ALP) has pledged to make renewable energy and responding to climate change risks a priority. Until now, there has been marked divergence between State Governments and Federal Government as to the importance of aggressive emissions reduction targets and the best path for the exit of thermal generation from the sector.

The ALP’s plan in relation to energy transition is to adopt a 43% emissions reduction target for 2030 and boost the share of renewables in the NEM to 82%. The ALP’s plan also includes investment for upgrading the electricity grid to fix energy transmission and drive down power prices.

We therefore expect the continuation of investments and new rules in support of policy goals. For example, several State governments have adopted policies to develop REZs and associated transmission support. The REZs are intended to encourage investment in renewable generation and storage projects.

Examples of Governments’ recent initiatives and developments include the following:

- NSW: The New South Wales Government has committed to develop five REZs, as part of the NSW Electricity Infrastructure Roadmap. This Roadmap is intended to coordinate investment in transmission, generation, storage and firming infrastructure as ageing coal-fired generation plants retire.

- Victoria: AEMO has been commissioned by the Victorian Government to seek tenders for six REZ projects. Additionally, the Victorian Government has announced its plans to launch Australia’s offshore wind industry, which has the potential to supply up to 13GW of power (approximately 20% of Victoria’s energy needs) by 2050. The Government released its Offshore Wind Policy Directions Paper in March 2022.

- Queensland: The Queensland Government has committed to develop three REZs across the State. The Queensland renewable energy target (QRET) requires that 50% of Queensland’s electricity consumption is sourced from renewables by 2030.

- WA: The Western Australian Government has committed to the State’s transformation into a significant producer, exporter and user of renewable hydrogen. The WA Renewable Hydrogen Roadmap identifies 26 initiatives the Western Australian Government is driving and supporting to realise the WA Renewable Hydrogen Strategy's mission and goals.

Meanwhile, the regulators at State, national and NEM-level are working to keep up with change - everything from the regulation of storage, ways to encourage competition and efficiency and the Energy Security Board’s reform agenda.

Manifestations for the Australian sector

The following themes arise from the aforementioned drivers:

- Development and innovation: There is appetite to build capacity and to do so to capitalise upon new and anticipated policy settings. This is increasingly including hybrid developments and renewables “hubs”, standalone storage and projects situated within planned REZs.

- Investment: Accompanying that, we are seeing significant funds being committed on private and public account in the sector. Major infrastructure and energy players are seeking opportunities to support Government-led developments and also vying to acquire major power and renewables assets in Australia.

- Diversification: Accompanying the investment imperative is also an acknowledgment of the need for the right mix of assets across the energy supply chain. For the incumbent “gentailers” that means pivoting away from thermal generation. It also means a revised strategy given the complementarities of other technologies and how that may match up with the end-user base.

- Consolidation: At the same time, we are also seeing some renewables players seeking to consolidate within the same functional level by increasing their portfolio of renewables in operation and under development.

- Paramountcy of the end-user: Opportunities for optimisation of energy use is playing out across the supply chain. This is resulting in a focus by energy suppliers on customer retention and additional income streams that might be garnered across smart technology, electric vehicles and other distributed energy solutions. Green electricity is also increasingly of interest to end users. Major corporates are demanding green alternatives through PPAs and on-site distributed energy alternatives. Small customers are also becoming more involved in their energy choices.

- Regulatory change and scrutiny: At the same time though, electricity supply remains an essential service and is a heavily regulated sector. There is a confronting amount of regulatory change occurring. There is also an ongoing focus upon energy affordability and transparency in market conduct, with both State-based and national regulators signalling their intention to be active in enforcement.

Qualifications and conclusions

The foregoing does not seek to represent that the transition will be smooth or without significant risk. Major projects must be built and the roles of longstanding contributors to the security of the power system are changing. There will be winners and losers.

There are also differing opinions about what is most important, how we best get there and when. For example, playing out right now is a major public stoush about the future of Australia’s largest vertically integrated generator and retailer. That organisation had been proposing to demerge its publicly listed business, in effect, siphoning off the thermal generation fleet from the customer base to create better scope to pivot. The strategy was abandoned in the face of opposition who were concerned that it would see the remaining coal assets remain in the market for too long and ignore opportunities to transition more effectively.

Fundamentally though, few are disputing that the power market decarbonisation shift is upon us and will be characterised by the factors identified in this article.

Norton Rose Fulbright has a leading energy team in Australia and globally, working at the forefront of the matters mentioned here. Please contact us should you wish to discuss any aspect.

Annexure: About the National Electricity Market

The NEM is the wholesale electricity market for the interconnected eastern and southern States and territories of Australia. Western Australia and the Northern Territory are not connected to the NEM and each have their own regulatory regimes and markets.

The NEM facilitates exchange between electricity producers and consumers through a pooled system, where output from all generators is aggregated and scheduled to meet consumer demand. The Australian Electricity Market Operator (AEMO) manages the wholesale market, oversees system security for the NEM electricity grid and is responsible for transmission planning.

Participation in electricity generation, transmission, distribution and supply is heavily regulated. NEM jurisdictions are subject to both State-specific frameworks and the National Electricity Law (NEL) and its subordinate National Electricity Rules (NER).

The Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) makes and amends the detailed NER. The Australian Energy Regulator (AER) is responsible for the economic regulation of the electricity transmission and distribution networks in the NEM and enforces the NEL, and National Energy Retail Law.

Thank you to Joana Becquet-Zardi for her assistance with this article.