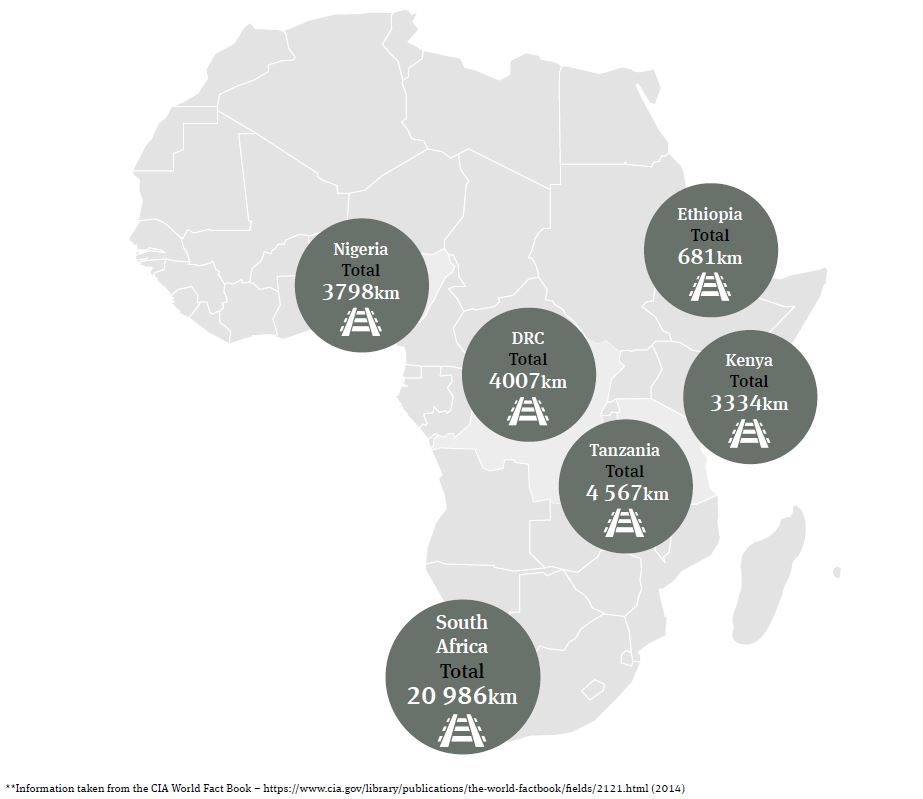

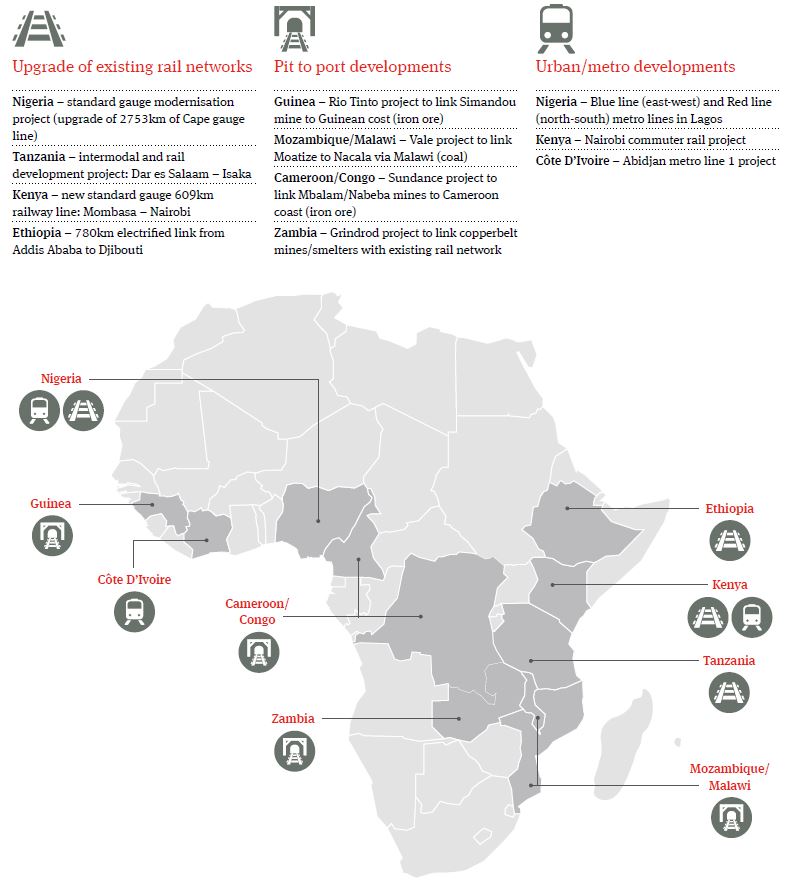

Rail projects in Africa can be broadly split into three categories.

1. Upgrade of existing rail networks

Existing rail networks in Africa are generally in fairly poor condition and require upgrades to rail infrastructure, stations and rolling stock, as well as network extensions, in order to adequately service passenger and freight demands. Often there will be existing state owned entities or other operators in place, and the planning and regulation of the various rail systems may vary in vision, content and implementation. Of course there are some areas, such as South Africa, where there have been well operated and maintained passenger services, regulated to some extent, as well as dedicated lines of high quality for the movement of commodities (a good example being the 861km Sishen- Saldanha iron ore line). In other areas, such as Namibia, local rail freight services have had to contend with a colonial rail infrastructure that cannot provide for extended freight rail services without considerable investment to upgrade the current track. The regulation of the rail system presents its own challenges: rail safety regulators may well be found for passenger rail issues – but economic rail regulators – or even operational regulators – may be needed to control issues such as tariffs, line access and utilisation.

There is also significant scope for confrontation between the state’s operation of rail infrastructure and rolling stock and the requirements of private operators. For example, long-term issues may arise if the operators do not adhere to standards placed upon them by the state, whilst the state in turn may utilise the line in a much less regulated way, leading to infrastructure, maintenance, environmental, health and safety and possibly social issues.

Whilst development of appropriate regulations is a positive step, longer-term investors will want some kind of certainty that this development will not radically affect their investment assumptions. If the cost of complying with new regulations cannot practically be passed to customers, then the investors may wish to look for an appropriate stabilisation regime, either in terms of exemption from application of new laws or a right to be kept in a financially neutral position.

2. Pit to Port developments

So-called “pit to port” developments may take place outside the regulated networks and often require the creation of new lines. These developments are mostly driven by mining companies or specialist logistics providers with varying levels of government support; there are good examples of major projects (both underway and planned) in Mozambique, Cameroon, Guinea and Liberia, amongst others. Investors in mining projects are used to taking the significant development risk involved in mining ventures and to that extent are also used to taking the risk of developing the associated infrastructure, but where the infrastructure provides a long-term public benefit, for example by opening up potential corridors for other mineral developments, there may be grounds for the government providing a greater level of commercial support, for example, by underpinning part of the debt and/or guaranteeing levels of traffic.

Third-party track access arrangements can be a key issue in these projects. Governments will want to avoid a situation where they have provided a long-term concession to a monopoly user which then effectively locks outs potential opportunities for others by refusing access; accordingly, many projects have built in the concept of an agreed methodology for allowing third party access based on the new users taking on an appropriate share of the initial infrastructure cost. In certain appropriate circumstances the state may also wish to impose a public service (passenger) requirement on the line, however there may be practical limitations to this given the very different requirements of passenger trains and freight trains (in terms of speeds and stopping times).

If a proposed line can practically facilitate other freight and passenger options, this clearly creates efficiencies and reduces dependency on a single commodity. This may be the point to consider whether the rail line can then be spun off as a stand-alone project, helping to develop a new “transport corridor” for the country. This in turn would reduce the financing burden on the mining project which originated the line, but at the expense of creating a dependency to the extent the line falls outside its control.

3. Urban/Metro developments

New metro projects often create their own standalone networks, but these projects can be highly technical, and therefore have their own complications in terms of structuring and funding. The general view is that it is very difficult to make greenfield metro projects self-funding, even in developed countries, and virtually all demand-risk metro projects have failed to meet their original traffic projections. In practice this means that the government would need to retain a significant portion (if not all) of the demand risk to make it externally financeable.

Nevertheless it is possible that this assumption could be challenged by developments in some major cities in Africa, where an urban metro scheme would offer significant time benefits against chronic congestion (where road infrastructure has not kept up with increased private car use), which may mean that passenger numbers may be high enough to secure appropriate financing even on relatively low fares. However, to date there are limited examples of existing urban/metro projects in Africa. The Gautrain project in South Africa provides a good example of a greenfield interurban rapid transit railway system; more recently a new light rail system has been inaugurated in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, being the first project of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa, conceived with the assistance of Chinese export finance.