Publication

Watt’s up: Regulatory round-up

Norton Rose Fulbright provides a monthly overview of the key updates to Australian East Coast energy regulation.

Global | Publication | September 2015

On 11 August 2015, the Australian Government submitted its long awaited Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Secretariat (UNFCCC Secretariat). Australia’s submission brings the total of INDCs received by the UNFCCC Secretariat to 26 comprised of 53 countries.1

INDCs are being submitted to the UNFCCC Secretariat in advance of the 21st Conference of Parties which will take place in Paris at the end of the year (COP21).

INDCs are indications of each country’s post-2020 emissions reduction targets and actions that the country intends to take, having regard to its own domestic priorities, circumstances and capabilities.

Countries which have submitted INDCs to date include the following:

| Submission No. | Country | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Switzerland | 27 February 2015 |

| 2 | Latvia and the European Commission on behalf of the European Union and its Member States | 6 March 2015 |

| 3 | Norway | 27 March 2015 |

| 4 | Mexico | 30 March 2015 |

| 5 | United States of America | 21 March 2015 |

| 7 | Russia | 1 April 2015 |

| 10 | Canada | 15 May 2015 |

| 15 | China | 30 June 2015 |

| 18 | New Zealand | 7 July 2015 |

| 19 | Japan | 17 July 2015 |

| 26 | Australia | 11 August 2015 |

The above table is correct as at 11 August 2015.

In the Lima Call for Climate Action adopted at COP 20 in December 2014, countries were invited to submit their INDCs well in advance of COP21. INDCs received by 1 October 2015 will be included in a synthesis report by the UNFCCC Secretariat on the aggregate effect of the INDCs, expected to be released by 1 November 2015. According to the UN Climate Change Newsroom, the INDCs aggregated in the synthesis report ‘will provide critical information necessary to tally the collective efforts and measure whether the world is on track for an effective agreement in Paris.’

While only countries (as parties to the UNFCCC) are able to submit INDCs, emission reductions are also key agenda items for organisations around the world. For example, on 2 July 2015, the Compact of States and Regions (comprised of sub-national governments from the North, Central and South Americas, Europe and Australia), released its first round of targets to reduce carbon emissions, ‘some as ambitious as 90% by 2050 and 100% by 2060’ (see press release here). Further, on 29 June 2015, Australian organisations participating in the Australian Climate Roundtable released a statement on their Joint Principles for Climate Policy, recognising that ‘Australia should play its fair part in global efforts to avoid 2°C and the serious economic, social and environmental impacts that unconstrained climate change would have on Australia.’

This update provides a brief overview of the INDCs received from the EU, United States of America (US), China, Canada and Australia, and also considers assessments of how those targets ‘measure up’ against each other.

The EU was the second party to submit its INDC to the UNFCCC Secretariat. The EU and its member states committed to ‘a binding target of at least 40% domestic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 1990’ levels. This commitment applies to all greenhouse gases not controlled by the Montreal Protocol (which was designed to reduce the production and consumption of ozone depleting substances in the atmosphere), covering energy, industry, agriculture, waste and land use, land-use change and forestry sectors, and will be implemented by way of legally binding, domestic legislation. The EU considers this target to be ‘fair and ambitious’ having regard to its ‘current undertaking of a 20% emission reduction commitment by 2020 compared to 1990’.

The full text of the EU’s INDC submission can be accessed here.

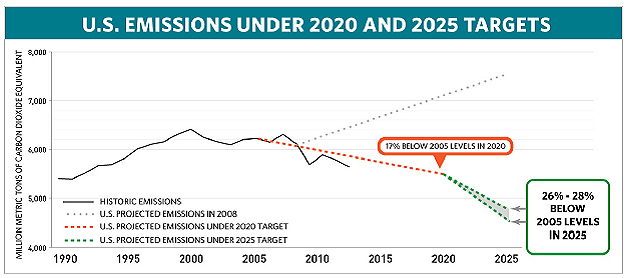

The fifth country to submit its INDC was the US, which ‘intends to achieve an economy-wide target of reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 26-28 per cent below its 2005 level in 2025 and to make best efforts to reduce its emissions by 28%.’ According to the US submission, achieving this target will require further emission reductions by the US, beyond its existing 2020 target and represents a ‘substantial acceleration of the 2005-2020 annual pace of reduction, to 2.3-2.8 percent per year, or an approximate doubling.’ This acceleration is shown in the graph below. The US target covers all greenhouse gases included in the 2014 Inventory of United States Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks, including emissions in the land sector but excludes international market mechanisms ‘at this time’. The target will be implemented through domestic laws as well as through associated existing and proposed regulations.

Source: US INDC submission to the UNFCCC Secretariat (31 March 2015).

The full text of the US’s INDC submission can be accessed here.

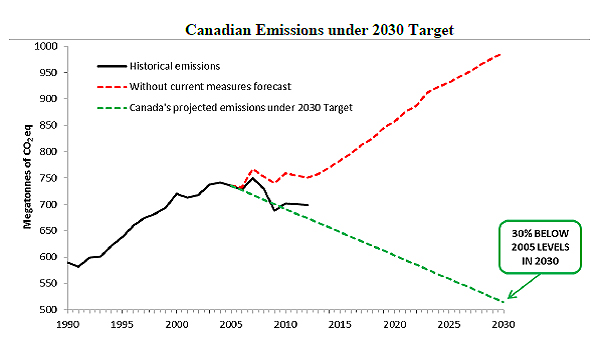

Canada submitted its INDC to the UNFCCC Secretariat in May 2015. Canada has committed an intention ‘to achieve an economy-wide target to reduce [its] greenhouse gas emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030.’ Canada considers this target to be ‘ambitious but achievable’. The proposed reductions are to be implemented through climate change legislative instruments across transportation, electricity and renewable fuel sectors, as well as through the introduction of additional regulatory measures. Canada also intends to account for the land and forestry sectors and will consider using international mechanisms to achieve its target. The following graph extracted from Canada’s INDC submission, shows its historical emissions and projected emissions, without the implementation of its emission reductions measures, as compared to Canada’s projected emissions under its 2030 target.

Source: Canada’s INDC submission to the UNFCCC Secretariat (15 May 2015)

The full text of Canada’s INDC submission can be accessed here.

China’s INDC submission was received by the UNFCCC Secretariat on 30 June 2015. China has committed to peak its carbon dioxide emissions by 2030, while making ‘best efforts’ towards peaking earlier. By 2030, it will also lower carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP by 60-65% from 2005 levels, increase non-fossil fuel consumption to approximately 20% and increase its forest stock volume by 4.5 billion cubic metres based on 2005 levels. China has also committed to continue ‘enhancing mechanisms and capacities… in key areas such as agriculture, forestry and water resources, as well as in cities, coastal and ecologically vulnerable areas’. In achieving these targets, China intends to, among other things, implement new national laws and strategies, improve regional strategies on climate change, develop low-carbon energy and industrial systems and control emissions from its building and transportation sectors.

The full text of China’s INDC submission can be accessed here.

On 11 August 2015, the Government announced that Australia will reduce greenhouse gas emissions so they are 26-28 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. According to the Australian Department of the Environment’s 2030 target document:

[i]n terms of reduction in emissions per capita and the emissions intensity of the economy, Australia’s emissions intensity and emissions per person [will] fall faster than many other economies…emissions per person [will] fall[s] by 50–52 per cent between 2005 and 2030 and emissions per unit of GDP by 64–65 per cent.

Australia considers this target to be ‘a strong, credible and responsible contribution to climate action’.

Australia intends to meet this target by ‘implementing a suite of Direct Action policies’, including ‘the $2.55 billion Emissions Reduction Fund and Safeguard Mechanism… [which will be] complemented by the Renewable Energy Target, energy efficiency improvements, phasing out very potent synthetic greenhouse gases, and direct support for investment in low emissions technologies and practices.’

The full text of Australia’s INDC submission can be accessed here.

Given the variety of baselines and differences in targets for emissions reductions versus intensity based targets, it is difficult to make a straight comparative assessment on how each country’s INDC ‘measures up’ against the others. It is also difficult for such an assessment to take into account the more subjective factors upon which each INDC is based, such as each country’s domestic priorities, circumstances, capabilities and ambitions. Similarly, it is difficult for comparative assessments of emissions targets to assess whether the target will be effective in addressing climate change. It is also important to remember that the INDCs do not simply outline a country’s plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions but can also cover such factors as national strategies, adaptation, finance, and technology development, factors that cannot be reflected in percentages alone.

However, comparisons are inevitably being made by various commentators. For example, in a recent article (see here), PwC compared and assessed the EU and US’s climate ambition, concluding ‘that the US appears to be as ambitious as the EU.’ Drawing on recent analysis from PwC, BusinessGreen has also produced an article (see here) which considers some of the INDCs submitted to date.

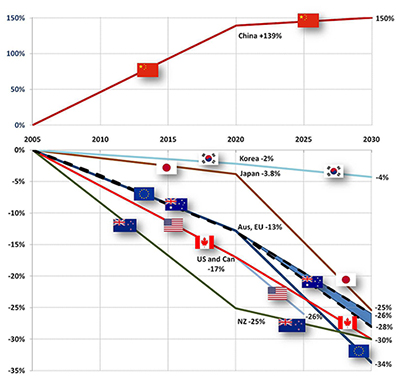

The following graph from Bloomberg New Energy Finance compares countries’ INDC emission target trajectories (including those of the US, EU, Canada and China), relative to 2010 levels for the base year.

Source: Australia’s emissions reduction target to 2030, Department of the Environment, August 2015

Over the next four months leading up to COP 21, nations will continue to submit their INDCs to the UNFCCC. All new submissions will be uploaded to the UNFCCC website, which can be accessed here. As part of this lead up to COP21, we will be undertaking a more detailed analysis of the INDCs of some key countries and their existing or projected tools directed towards achievement of their respective targets.

The European Commission is comprised of 28 member states.

Publication

Norton Rose Fulbright provides a monthly overview of the key updates to Australian East Coast energy regulation.

Publication

Le 9 octobre 2025, l’Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) a publié pour consultation un projet intitulé Ligne directrice sur la gestion du risque lié aux tiers (Ligne directrice de l’AMF).

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025