Publication

Watt’s up: Regulatory round-up – September 2025

Norton Rose Fulbright provides a monthly overview of the key updates to Australian East Coast energy regulation.

Author:

Global | Publication | November 2017

As previously updated, businesses have until 1 July 2018 to transition to a new system of country of origin labelling for food products in Australia. The incoming Country of Origin Food Labelling Information Standard 2016 (Standard) imposes stricter labelling requirements on “priority”, as opposed to “non-priority”, foods and is intended to help consumers better understand where their food comes from.

Uncertainty comes as part and parcel of any regulatory overhaul and it’s too early to tell how some aspects of the new system will work in practice. In this update, we look at the different requirements in place for priority and non-priority foods, and the types of claims businesses can make on their packaging under the new regulations.

It is important to note that the Standard does not apply to all foods. For example, food sold for immediate consumption at a café or restaurant, or food sold on the premises where it has been produced, such as at a bakery. However, assuming that the Standard does apply, labelling obligations depend on whether the food is classified as a 1.) priority food or 2.) non-priority food.

Businesses should assume that their food products are priority foods unless they fall into one of the seven non-priority food categories set out in the Standard. The categories for non-priority foods are: 1.) seasoning, 2.) confectionary, 3.) biscuits and snack foods, 4.) soft drinks and sports drinks, 5.) tea and coffee, 6.) alcoholic beverages, and 7.) bottled water.

Make sure to check the Standard thoroughly before deciding your food is non-priority as some foods, like muesli bars, are defined as priority despite being commonly thought of as snack foods.

If your food is non-priority, you only need to include a text statement identifying the country of origin (eg, “Product of Australia” or “Made in Italy”). You can use the same labelling system as is required for priority foods if you want, but if you choose this option you have to comply with the Standard as if your product was a priority food. This could be an attractive option for businesses to standardise their approach across all products, particularly if the new Standard proves popular with consumers.

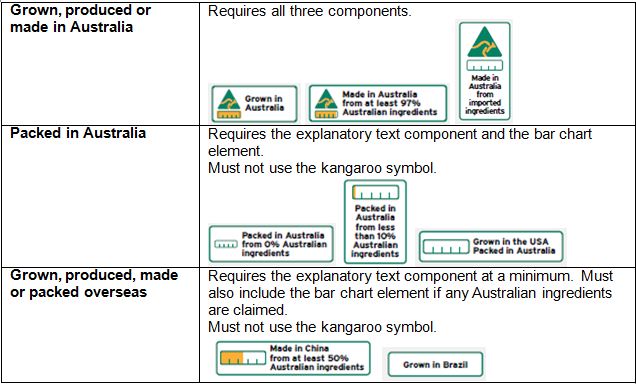

All priority foods are required to bear a “standard mark label”, which may consist of up to three elements; (1) the Kangaroo symbol; (2) a bar chart indicating the proportion of Australian ingredients; and (3) explanatory text indicating the food’s country of origin and the percentage of Australian ingredients. All standard mark labels must be contained within a clearly defined box.

The exact requirements of the label depend on the country of origin and whether the food was “grown”, “produced”, “made” or “packed” there. The below table sets out some rules of thumb and example labels.

“Grown” and “produced” claims are likely to be very similar, however, the Standard advises that you should use a “produced” claim for products containing ingredients that aren’t grown, such as sauces containing water or salt (neither of which can be “grown” according to the Standard).

The rules for claiming that a priority food was grown/produced in Australia are stricter than for other countries. To make a “grown/produced in Australia” claim, all ingredients must have been grown/produced in Australia. Furthermore, if there is more than one ingredient, all or virtually all of the processing must have occurred in Australia.

For other countries, a “grown” or “produced” claim can be made if each significant ingredient was grown or produced in that country and all or virtually all processing also occurred there. Whether an ingredient is significant depends on the nature/function of the food, not the proportion of the ingredient.

The less onerous “significant ingredient” test also applies to non-priority foods grown/produced in Australia but, as mentioned, if you wanted to use a standard mark label for a non-priority food you could only do so if all ingredients were Australian grown/produced.

The “made” claim is broader than the grown/produced claims. You can say your product is “made” in Australia or another country if it underwent its last substantial transformation there. A food undergoes a substantial transformation in a country if the food:

The “last substantial transformation” test is likely to prove confusing for a lot of businesses. Whilst unclear how the ACCC will apply the test you should be aware that:

If your food doesn’t pass the “last substantial transformation test” but it is packed in Australia, you could make a “packed” claim. You will still need to declare the proportion of Australian ingredients in the products (including if there are no Australian ingredients), and you will not be able to use the kangaroo symbol. The below label is one such example.

![]()

Unless the overseas processing is very minor, making a “grown/produced/made in Australia” claim may contravene the Standard for goods processed overseas.

In the case of very minor processing, you would need to declare the specific nature of the processing on the packaging (see the below example).

Also bear in mind that if any foreign ingredients are added to the food during overseas processing you cannot claim the food is grown or produced in Australia, no matter how minor the processing.

If the processing amounts to a substantial transformation, you will need to declare that the product was made in that country. You can, however, add explanatory text and a bar chart to indicate the percentage of Australian ingredients.

![]()

The changes canvassed above are aimed at creating greater clarity for consumers, but they can be onerous for businesses to apply in practice. Businesses that do not comply with the Standard risk penalties of up to AU$1.1 million. Therefore, they cannot be ignored.

As the changes are bedded down in practice, there will be some uncertainty and it’s too early to tell how some aspects of the new system will work for businesses. Businesses will need to accept some pain during the implementation process, but it is hoped that as the changes become the norm, they will also create benefits for consumers to drive market growth.

Publication

Norton Rose Fulbright provides a monthly overview of the key updates to Australian East Coast energy regulation.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025