We have seen that it is not straightforward to determine the extent to which a Constitution is legally binding and who can enforce it. Assume, however, that the User has submitted a transaction that contains a reference to the Constitution and that this constitutes a legally enforceable contract and that the counterparties to this contract include the Counterparty, the Block Producer, other block producers and other users of the blockchain. Even with all these assumptions, it is not clear how certain obligations in the Constitution are to be enforced.

The Constitution is, from a legal perspective, a private contract enforced by the law of consensual obligations but, from a social or technological perspective, a public statement of general rights and obligations to the community as a whole. Communal obligations based on moral precepts do exist in modern legal systems, but they have generally evolved from being enforced by individuals to being enforced by the state using criminal law principles. We shall see below that enforcement of some obligations of the Constitution is analogous to enforcement of the criminal law in a primitive legal system without a developed role for the state. The closest analogy in developed legal systems is membership of a private club with multiple participants – these are often considered as quasi-public relationships that have some private and some public characteristics.

We consider several types of obligation in turn to highlight the issues that may arise.

Governing law

The governed blockchain allows parties to exchange binding promises that will execute automatically without the interference of the courts. So why is there a need to include a governing law clause in any agreement? In fact, somewhat counterintuitively, if parties want to minimise national laws impinging on their agreement, it is essential for them to include a governing law clause. Otherwise, in the event of a dispute over a binding agreement, courts (or arbitrators) will simply decide for themselves what the governing law of the agreement should be and then proceed to apply that law to the agreement.

Not all governing laws are the same. Some will generally respect the choices of the parties and seek to interpret the agreement in accordance with their intentions. Others will not: they may incorporate additional rules – such as consumer protection – or annul certain obligations – such as payment of interest. Parties that value freedom to create their own agreements must ensure that the law that governs their agreement is one of those that is commercial and aims to ‘get out of the way’ rather than one of those that takes a paternalistic approach.

The distributed, cross-border nature of the blockchain makes it difficult to predict what governing law would be chosen for a particular contract or for the Constitution. Parties would have to consider every rule in every paternalistic system of law that might be applied to their contract. Fortunately, there is a simple solution. Parties can make an express choice of governing law in their contract. In most courts, a choice of governing law in a contract is respected and will be given effect, even when it is the governing law of a country other than that where the court is situated. By expressly choosing a predictable, commercial law to govern their contract, parties can avoid a governing law that interferes with their rights and obligations.

At first, it appears that there is a problem in deciding whether the governing law clause works: what system of law do you apply to determine that question? (In computing terms, this would be characterised as a ‘bootstrapping’ issue.) However, most legal systems – including all those in the EU – have adopted a practical solution to this question. A purported choice of governing law is used to determine whether that choice of governing law is binding. So, for instance, if the Constitution contains an express choice of English law, then English law principles will be used to decide whether it constitutes a binding contract – including the governing law clause. This means that a choice of governing law provides a clear origin for analysis of the Constitution and its effects and, by extension, transactions that take place on the blockchain. Any Constitution should contain at the very least a governing law clause.

Bilateral obligations

The Constitution may contain provisions that are deemed to be incorporated into particular contracts made on the blockchain, such as dispute resolution clauses. Assuming that the Constitution is itself a contract then, provided that the Counterparty and the User are both party to it, these bilateral obligations will be incorporated into the separate agreement between the User and the Counterparty and will be enforceable as with any other contractual obligation. This will apply, for instance, to arrangements between dApp Providers and end-users who are employing their distributed applications, insofar as those end-users are also Users – that is, direct participants in the blockchain.

Some bilateral obligations are only enforceable if they satisfy particular formal requirements – such as being ‘in writing’ or being signed by the parties. Arbitration clauses and other dispute resolution mechanisms often fall into this category. If these clauses are included in the Constitution and incorporated into individual agreements by reference, the Constitution itself may have to satisfy these formal requirements.

Smart contracts will often be used to document bilateral obligations between a User and a Counterparty. Smart contracts inherently deal with issues of evidence and intention that are behind some formality requirements – but, until legal systems add rules dealing specifically with smart contract, these formalities will still need to be satisfied.

Civil and criminal

The Constitution may contain obligations that are not simple bilateral promises. It may contain, for instance, promises to do or to refrain from certain behaviour or undertakings to act in accordance with certain general norms or values. An example of the former is a promise not to carry out a distributed denial of service attack (DDOS) on the blockchain; an example of the latter is a promise to treat other users of the blockchain with respect and consideration.

Some of these promises may be too vague to constitute legally binding obligations. This does not mean that they are useless: their efficacy will be in establishing moral or cultural norms. Others will be specific enough to be enforceable – but they are not promises made to particular individuals and it is unclear who will enforce them and what enforcement would consist of. Mechanisms to allow individuals to enforce them on behalf of the community may be needed, such as those used in enforcement of open source licences.

Take the promise not to carry out a DDOS. Assume that a User carries out a DDOS attack some time after posting a transaction with a hashed reference to a Constitution containing a promise not to carry out a DDOS. The Counterparty is able to enforce the private contract embodied in the Constitution against the User. In principle, this means the Counterparty could sue the User for damages. But the Counterparty might not have suffered any damage. Even if other users are also party to the contract, they may also have suffered minimal damage. Each person could only sue for the damage that they had suffered. In the case of the Block Producer, this might be significant. In most cases, there would probably be little practical incentive for any person to sue for breach of this obligation. It seems unsatisfactory to leave enforcement subject to the vagaries of individual loss or to those motivated by community spirit.

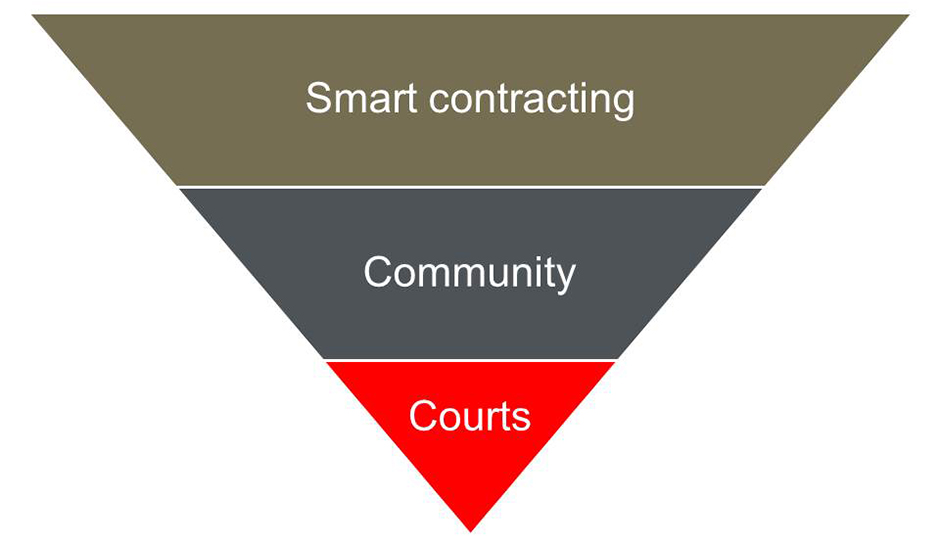

The problem here is that a private consensual agreement is being used to impose obligations that are more usually found within criminal law, in that they relate to norms of behaviour that affect the community as a whole as well as individuals. Provisions in the Constitution that fall within this definition will be referred to as quasi-criminal obligations. Private and criminal liability often go together – an individual may suffer damage from a crime for which he is entitled to be compensated. By a quasi-criminal obligation, we are referring to the obligation owed to the community, over and above the damage caused to any one individual. In many legal systems, there has been a gradual development of collective enforcement of criminal obligations by centralised authorities, replacing ad hoc individual enforcement. It may be that communities centred around blockchain Constitutions will need to go through a similar process for quasi-criminal obligations.

Apart from quasi-criminal obligations, the Constitution may also contain quasi-regulatory obligations. These are obligations relating to areas such as data privacy, initial coin offerings and mode of payments. Unlike quasi-criminal obligations, quasi-regulatory obligations do not apply to all users all the time. A dApp Provider might choose, for instance, to fall within the data privacy regime of the Constitution. If it does, Users will have the assurance that their data is being protected according to the regime and this will presumably bring benefits to the dApp Provider. But if the dApp Provider opts into the regime and then contravenes any of its obligations, this will be a breach of the Constitution with similar consequences to breach of a quasi-criminal obligation.

Effective sanctions do exist within the private consensual realm, particularly if enforcement is delegated to an institution internal to the community. Apart from monetary claims, which might include penalties in some circumstances, the community as a whole has an additional powerful tool: expulsion. Preventing a malefactor from future engagement with the blockchain is an effective sanction and could be the ultimate deterrent in enforcing quasi-criminal and quasi-regulatory obligations in the governed blockchain.

The creation of quasi-criminal and quasi-regulatory obligations suggests that governed blockchains may be able to address some of the worst examples of anti-social behaviour seen in permissionless blockchains. Traditional regulators might even be inserted into the dispute resolution mechanisms – whether as participants in arbitration or with some special status. While still fully decentralised, the governed blockchain may be able to filter out some universally unacceptable criminal behaviours.

Note that even where quasi-criminal and quasi-regulatory obligations are clearly set out in the Constitution and coupled with effective powers of enforcement, it is possible that a court may override them, for reasons of public policy. A court may decide that some obligations are inherently public and should not form part of private contract law. As courts have the power to confiscate property and imprison individuals within their jurisdiction, they cannot ultimately be ignored. So the scope for the Constitution to form a complete and self-contained regime may be limited.

JAC: the JAC amendable constitution

JAC stands for JAC Amendable Constitution. It refers to a Constitution that can amend itself. In other words, the Constitution includes a mechanism for changing all or certain terms of the Constitution, including a method by which assent to a change is measured and recorded. This might be a voting mechanism, for instance, or conditions on the Block Producer including a transaction that has a hashed reference to an amended Constitution.

The JAC is not inconsistent with contract formation in most governing laws. It is not uncommon for contracts to contain provisions limiting how they may be amended. So, in principle, the JAC can include a wide variety of different amendment mechanisms. It may even be flexible enough to regularise blockchain forks, making them a Constitutional activity, rather than something occurring outside the normal parameters of the blockchain community.

The difficulty with the JAC is not in enabling variation of the Constitution but in reconciling different versions. We have seen that there may be multiple instantiations of a single Constitution, involving different sets of parties. Where there are, in addition, multiple different versions of the Constitution, it may be problematic to determine which version of the Constitution governs the relationship between two Users who have entered into different versions at different times. The JAC should itself contain provisions to resolve these questions.

Dispute resolution mechanisms

One of the key benefits of a Constitution is the ability to insert dispute resolution mechanisms. These may encompass disputes about enforcement of the Constitution itself or they may be incorporated by reference into individual arrangements between the User and the Counterparty. In this way, a single consistent method of dispute resolution could apply to a large proportion of activity on the blockchain.

A bespoke dispute resolution mechanism automatically minimises many of the perceived limitations of the blockchain. Questions as to governing law and jurisdiction are, by definition, resolved. Issues as to reconciling code with natural language in smart contracts, dealing with bugs and coping with external information provider failure can be determined fairly. For more on types of dispute resolution mechanisms and, in particular, the advantages of arbitration, see the forthcoming chapter Blockchain Disputes: Risks and Resolutions in Unlocking the Blockchain, which will be available here.

A particular concern for arbitration clauses is that there may be formalities needed to make them binding. For instance, an arbitration clause may have to be in writing or be written in a particular language or signed by the parties. This may limit how arbitration clauses are included in the Constitution and whether they can be incorporated by reference.

Another concern for arbitration clauses is multilateral enforcement. Arbitration, as a private method of dispute resolution, has to be adapted where it is necessary for it to bind a larger group of people. For obligations in the Constitution that are inherently multilateral – such as promises to the community as a whole – drafting an effective arbitration clause will need careful thought.