From equity to franchising: investing in esports

This article is part of a series of Norton Rose Fulbright articles about legal, regulatory and governance issues facing the e-sports industry.

With revenue from esports and its supporting ecosystem projected to multiply fivefold over the next three years,1 investors are growing bullish about its potential to rival traditional sports as a revenue opportunity.

How does one then enter this industry? Apart from the other approaches such as sponsorship and licensing rights explored in other parts of this series, this article looks at how companies and individuals may invest in teams, and how teams may tap on the franchising arrangements used by major esports leagues.

Investing in companies and teams

Due to organisational similarities between esports and traditional sports, traditional sports companies and athletes have dominated the investment scene from its early days. The investment structure to be adopted would depend on the stage of growth at which the team is seeking investment, the investors’ risk appetite, their ability and willingness to participate in decision-making processes, and each party’s relative negotiating position.

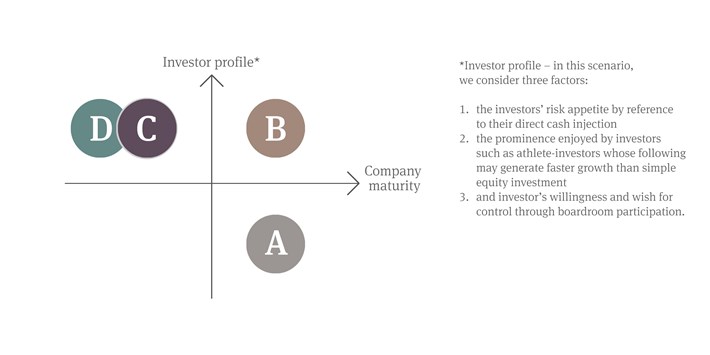

From an investor’s perspective, there are four main approaches to investing in companies and teams in the esports sector. Considering just two factors for the time being – the investor profile and company maturity – their relationship can be understood graphically:

A. Cash investment – entails direct equity participation either individually or as part of a larger consortium or investment group (for example, through a venture capital fund).

B. Cash investment coupled with boardroom participation – more suited to companies and investors operating in a familiar market where the investor may leverage on its experience, insights and networks. By participating in the decision-making process through a board seat or rights of consultation, this model goes beyond a simple financial commitment.

C. Hybrid endorsement model – combines cash investment for shares with non-boardroom participation whereby the investor enters into a separate endorsement agreement, usually through their image rights companies, with the esports company. This approach is generally more suited to investors who seek to hedge their equity risk inherent in early-stage companies by combining potentially discounted shares with a separate revenue stream through the endorsement agreement, a revenue sharing arrangement and/or a minimum guarantee element.

D. Sweat equity/equity compensation – this approach is mostly seen in early-stage companies which do not have the cashflow to commit to an endorsement agreement with the athlete-investor who, in turn, may be reluctant to bear direct financial loss in injecting cash. Instead, the athlete-investor endorses the company and grants its image rights in exchange for equity.

In each structure above, legal considerations impact the attending documentation:

- Articles of association – from an investor’s perspective, the rights attaching to the shares should not be restricted by the company articles. This may include drag-along and tag-along rights and not disapplying statutory pre-emption rights to protect against dilution. Further, the investor may also seek a right of first refusal as part of the pre-emption provision on another shareholder’s transfer of shares to a third party. The investor may even want a right to appoint a director to a board given a minimum threshold of investment.

- Subscription agreement and shareholders’ agreement – the investor may seek to agree with the other shareholders (some of whom would likely be founders) the disposal mechanics of shares in certain events such as in a transfer to a third party or where a transfer results in a change of control. The investor may further seek the right to receive periodic financial information from the company and restrictive covenants against relevant stakeholders such as non-compete provisions.

- Corporation authorizations – such ancillary documentation includes board and shareholder resolutions required to allot new shares and generally execute the investment. Follow-up work to register the documents at Companies House is also a legal obligation in the UK.

- Sponsorship – as the teams gain prominence, both the team itself and the investors may consider the licensing of image rights for gaming peripherals such as lifestyle products and collectibles (e.g. jerseys and in-game skins), as well as the entering into revenue-sharing arrangements. It would be useful to consider and document these arrangements prior to investment, but some may consider it more expedient to agree to negotiate these points as they become more relevant.

- Employment contracts and key man clauses in the investment agreement – individual players may frequently drive revenue through their following and viewership on streams. Given the role of key players and team managers to a team’s valuation, satisfactory review of existing employment contracts and their renegotiation where necessary may be a precondition to completion.

Franchising

There are two main approaches for teams to organize themselves into a league: the franchise model American sports-style, or the “promotion-or-relegation” model a la English football. Franchising is preferred by games such as Overwatch and League of Legends which constitute a commanding share of esports audiences and fans. Structurally more familiar to investors and perceived to lend stability to teams, the franchise administers the entire league’s advertising, sponsorship, streaming and merchandising opportunities. For example, before the franchising arrangements were put into place in 2017, the North American League of Legends Championship Series (NA LCS) operated by a relegation model and attracted less sponsorship, with relegated teams enjoying less viewership coupled with no certainty of promotion which made companies very hesitant to inject money into something that could very easily lose its relevance.2

Revenue derived is in turn shared amongst the teams. It is estimated that 70-80 percent of revenue come from sponsorship and advertising,3 with the share from media rights slated to grow alongside the shift towards online streaming and viewership.4

The cost of a franchise spot for prospective franchisees as at 2018 is US$10-13 million for NA LCS, or up to US$20 million for Overwatch League (OWL) teams. These numbers are slated to grow rapidly as the esports ecosystem expands.

And the model seems to be paying off. OWL is reportedly expanding to include eight new teams at fees of between US$35 – 60 million each (depending on amongst others, the population of the city the team will represent, and the valuation of teams currently in the league). OWL entered into a two-year agreement for exclusive streaming rights in all regions other than China for US$90. Globally, it appears that the franchising model is the first consideration for investors and teams participating in organised esports.

Esports on the rise

With esports continuing to drive headlines around the world, it appears that the industry is destined for heady days. Eventually anchored around a franchise model, participation in the largest leagues begins with careful consideration of the risks and synergies between teams, players, companies and investors from day one. With the right legal structures in place, investors can go ahead and get their game on.

[1] https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/infographics/e-sports/report.pdf

[2] https://loupventures.com/esports-franchise-economics/

[3] https://loupventures.com/esports-franchise-economics/

[4] https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/infographics/e-sports/report.pdf