Latest trends in English banking litigation: Duration and resolution of claims

Our latest analysis of trends in banking litigation uses sophisticated statistical techniques to report on how long cases last and when and why cases settle. Surprisingly, only one factor affects the overall duration of banking litigation: whether fraud has been pleaded. Fraud cases last longer with over 25% of fraud claims lasting more than three years compared to just 10% of claims without fraud (a significant number of fraud cases also take more than five years to resolve). A non-fraud case is more than half as likely to settle over any given time period as a fraud case.

How long do banking litigation cases last?

The second question any litigant asks (after ‘will I win’) is ‘how long will it last’. Traditionally, this question is answered by supposition and anecdote – there are no public sources that cover this sort of litigation data. Numbers are available for cases that reach judgment, but this is only a small proportion of total litigation. Norton Rose Fulbright’s proprietary Court Intelligence Database covers all large-scale banking litigation in the English courts, whether or not it reaches judgment, recording details of the type of claim and its progress. The statistical techniques used to analyse this data are set out in the Appendix.

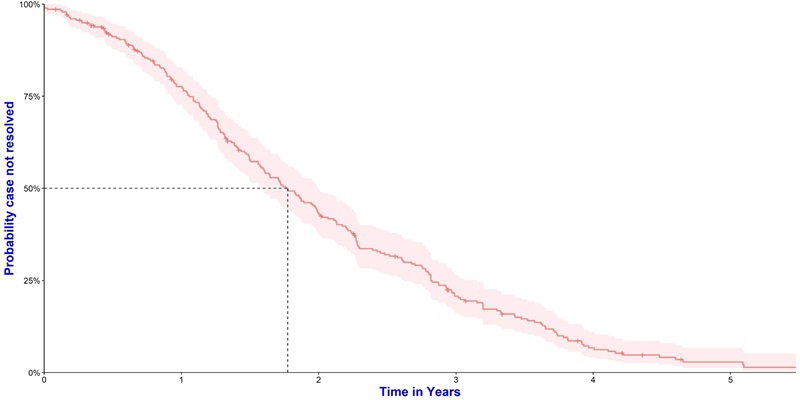

The overall distribution of cases is set out in Figure 1. The average case lasts about twenty-one months (our endpoint here, and throughout, is any of judgment, settlement or discontinuance of the claim). About half of all cases last between one and three years. Figure 1 shows the duration of cases in detail: it starts at zero days showing that 100% of cases are still extant. For the first six months, this declines slowly and then there is an abrupt rush of cases ending – at this stage, these are overwhelmingly settlements and discontinuances rather than judgments. The pace of decline stays roughly steady thereafter, so that at any one time the chance of a case ending is the same and the overall number of cases dwindles to a very small proportion after about five years.

Figure 1: Duration of all banking litigation disputes in the High Court (with 95% confidence intervals)

Surprisingly, only one factor affects the overall duration of banking litigation: whether fraud has been pleaded

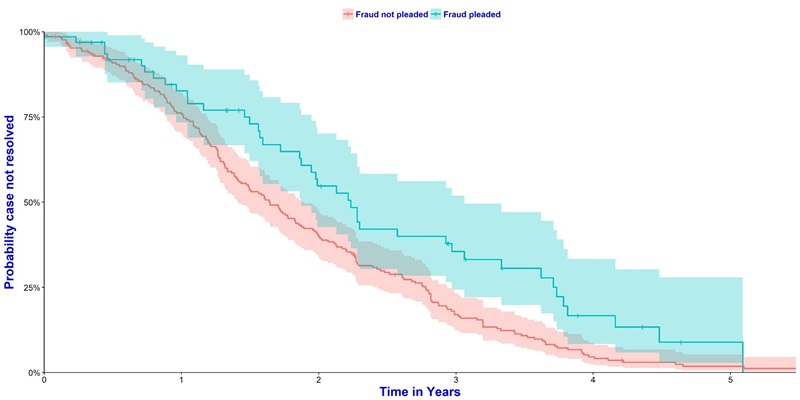

The subject-matter of the claim, whether it concerns capital markets, loan finance, derivatives and so on, does not affect its duration, once fraud has been taken into account. Figure 2 shows the distribution of cases where fraud has been pleaded and where it has not been pleaded. The two lines clearly diverge (and statistical analysis shows less than a 1% chance that this difference could have arisen naturally). Cases where fraud has been pleaded last longer. The halfway point for cases without fraud is about a year and a half; the halfway point for cases where fraud is pleaded is just over two years. And a much higher proportion of fraud cases last much longer: almost a quarter of fraud cases last longer than three years and a significant amount go on for longer than five years. Less than 10% of cases without fraud last for longer than three years. Overall, the magnitude of the effect is that, over any period of time, a fraud case has only 60% of the likelihood of settling as a non-fraud case or, to state it the other way round, a non-fraud case is more than half as likely to settle over any given time period as a fraud case.

Both fraud and non-fraud cases show the anomaly that is also apparent in Figure 1 – the slow rate of decline for the first six months – although fraud cases arguably show this pattern to a greater extent. What this shows is that cases are much less likely to settle in the first six months after the claim form is served. Perhaps this reflects that when a dispute first arises, the parties will often try to settle it by direct negotiation. It is only when this approach fails and the parties have reached a stalemate that a claim form is served, so that a resolution of the dispute is unlikely in the immediate aftermath of this step. This suggests that, when formulating litigation strategy, the period immediately before issue of the claim form should be prioritised for settlement and resources should not be allocated to resolution immediately after the claim is initiated.

A separate analysis of only those claims that have already been completed also reveals fascinating differences between fraud and non-fraud cases. Of all completed cases, those that ended in judgment lasted on average 812 days (two and a quarter years) and all other cases lasted on average 635 days (one and three-quarter years). There was no significant difference between cases that specifically ended in settlement and all those that did not end in judgment. This outcome is reassuring rather than surprising – it would be strange if cases that settled took longer than cases that went all the way to judgment.

Figure 2: Duration of banking litigation in the High Court where fraud is pleaded and where it is not pleaded (with 95% confidence intervals)

Where fraud is pleaded, the dispute is more likely to go all the way to judgment

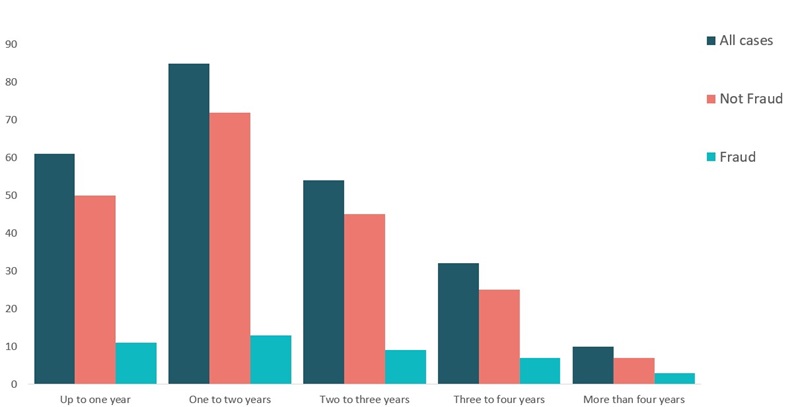

Figure 3 shows the duration of completed cases – overall and where fraud is and is not pleaded. Although it is not immediately apparent just from looking at the graph, there is a significant difference between fraud and non-fraud cases, as was revealed by the more sensitive duration analysis shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Fraud shows up in the completed cases analysis in the difference between cases that end in judgment and those that do not. Of 206 completed non-fraud cases, 47 ended in judgment; of 43 completed fraud cases, 18 ended in judgment. That is, about a quarter of non-fraud cases ended in judgment, whereas for fraud cases this was nearly half. Statistical analysis shows that there is less than a 1% probability that this discrepancy could have arisen by chance.

Figure 3: Duration of completed banking litigation cases in the High Court where fraud is pleaded and where it is not pleaded

Takeaways

There are various practical conclusions that can be drawn from this analysis:

- Estimates of how long a dispute will last and how likely it is to settle should be based on the figures given here, where account is taken, above all, of whether fraud is pleaded – half of all cases last between one and three years, but fraud cases last on average over two years and almost a quarter last longer than three years;

- Over any period of time, a non-fraud case is more than one and a half times more likely to be resolved than a fraud case;

- Efforts to settle a dispute, especially one involving fraud, should be not be unduly focussed on the six months immediately after the claim form is issued – the periods before and after this time may be more conducive to settlement; and

- When formulating strategy, account should be taken of the insight that fraud cases last longer and are less likely to settle.

This analysis is based on our proprietary cloud-based ‘big data’ Court Intelligence Database. For over five years, it has kept track of detailed data on large-scale banking litigation cases started in the High Court. We continue to collect data and we will present further insights in the future. Our October 2021 post analysing trends in the types of banking litigation disputes is here.

Statistical analysis

Duration analysis covered 284 cases; 24% featured fraud, 40% misselling, 19% contractual interpretation, 42% derivatives, 13% capital markets, 9% loan finance, all other categories were below 5%.

Cox proportional hazards multivariate regression was used to analyse duration. Fraud was found to be the only significant covariate (p-value = 0.0036) using a stepwise selection method. Analysis of residuals and bootstrapping were used to confirm Cox regression conclusions and assumptions – there was evidence that the assumption of proportionality was not supported for the first six months after issuance. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to describe incidence of determination of disputes.

Completed cases were assessed using a chi-squared test. Fraud was found to be a significant factor in whether disputes were determined by judgment or otherwise (p-value = 0.0097). Analysis was performed using R, version 3.5.0.