Until January 1, 2021, the only restructuring options available to distressed companies in Germany were either judicial insolvency proceedings (with or without self-administration) or purely consensual out-of-court restructurings with the consent of all creditors. Although restructuring can often be achieved through out-of-court negotiations, there is always the risk of individual dissenting creditors or minority shareholders taking actions that threaten the success of such restructurings.

With Germany's new Act on the Stabilization and Restructuring Framework for Businesses (StaRUG), a path has now been created as of January 1, 2021, which provides a pre-insolvency restructuring proceeding with court involvement and the possibility of orders/regulations that will bind the affected creditors. In other European countries, such proceedings have long been the order of the day. In Germany, the English scheme of arrangement has often been cited as an example of this type of process. In particular, the low entry requirements for this procedure have led to a wide range of pre-insolvency applications in the UK and certain other common law jurisdictions.

The initial practical experience with and uses of StaRUG are currently underway in the German market. Despite its recent vintage, it is clear that StaRUG will have an important impact on the design and structures of future distressed M&A transactions in Germany, which in the past have taken the route of an out-of-court restructuring. This is particularly relevant in the case of complex stakeholder and financing situations, the lack of a company succession solution or for the purpose of portfolio streamlining, cash generation through carve-out transactions or through separation of non-core assets. In Germany, the current distressed markets are those directly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e. tourism, hospitality, aviation, mechanical/plant engineering, sports, retail and leisure) and in addition, the so-called "zombie" companies with limited and reduced financial flexibility and declining debt capacity. Companies with a need for start-up financing or otherwise with refinancing difficulties are also subject to distress.

General impact of the StaRUG-scheme on the M&A process

First of all, management is in charge of the StaRUG-scheme. However, upon application or, under certain conditions, ex officio, a so-called restructuring officer (Restrukturierungsbeauftragter) can be appointed. Nevertheless, the restructuring officer has a more supervisory and supportive function. Therefore, a fundamental change is the far-reaching freedom of management to shape and organize the entire M&A process as part of the restructuring. In this phase, however, the management is still bound by the instructions of the company's shareholders. At the same time, the interests of creditors, and in particular secured creditors, must nevertheless be taken into account by management. In particular, the M&A process in a StaRUG framework should not be used by management to delay and drag out the restructuring process to the detriment of creditors or to implement measures that endanger or disadvantage creditors. Such measures could cause the StaRUG-scheme to fail during the subsequent judicial review stage. At a minimum, the creditors must be placed in a better position than they would have been without the proposed StaRUG-scheme.

Pursuant to StaRUG Section 29, the company's access to the StaRUG restructuring framework is available as of the company's imminent illiquidity. However, the distressed company must be neither illiquid nor over-indebted, which legally would require management to commence an insolvency case within a short time period (e.g., between three to six weeks). This means that the initiation of the StaRUG-scheme itself - with or without an M&A process - can only occur with the consent of the shareholders. In contrast, the M&A process in a traditional insolvency proceeding in Germany involves strict rules and control by an administrator following the commencement of the case. In a StaRUG scheme, it is possible to work out a more flexible or tailor-made solution and takeover strategy in advance of the StaRUG filing. Although the focus is likely to be primarily on financial restructurings, this can certainly be flanked by operational restructurings as a reaction to either the financial or operational causes of the distress.

The possibility of early initiation of a debt-equity swap pursuant to StaRUG Sec. 7 (4) also offers an interesting restructuring option in the context of a lender's loan-to-own strategy, which could result in the complete loss in the value of equity. In addition, all other permissible measures under company law, such as (i) a capital reduction or increase, (ii) the use of in-kind contributions of equity, (iii) subscription rights or (iv) the payment of compensation to departing shareholders, are also possible in a StaRUG restructuring plan. These measures could be agreed in advance with a potential new investor or acquiror. The broad portfolio of options thus significantly increases the attractiveness of the target company for potential suitors.

Above all, financial acquirors (e.g., private equity companies or hedge funds) should be best positioned to benefit from StaRUG. While strategic acquirors usually take greater risks in distressed M&A transactions due to their better knowledge of the industry and ability to conduct due diligence quickly and efficiently, financial investors are expert at minimizing risk through creative transactions. Thus, financial investors could benefit from StaRUG's flexibility in allowing the company and acquiror to shape a transaction in the restructuring plan under the StaRUG-scheme.

The StaRUG-scheme addresses the issue of dissenting creditors by creating the right to cross-class cram down. In this context, a variation of the absolute priority applies, i.e. overruling of a dissenting creditor class is only possible if the members of the class have an appropriate share in the so called plan's "value" (Planwert). However, there are exceptions that provide the court with much leeway; for example, different treatment of creditors of the same rank is possible if this appears "appropriate" in the individual case. Dissenting creditors can therefore no longer rely on a successful hold-out strategy under the StaRUG-scheme.

In addition, intra-company third-party collateral or credit support (such as guarantees or letters of comfort) can also be included as part of the restructuring plan, which can lead to significant simplifications in M&A transactions within complex (holding) structures.

By utilizing a stabilization order (the so-called moratorium), secured lenders can be denied access to their collateral for an initial period of three months. The maintenance of the status quo offers a decisive time advantage for both the value calculations and the M&A transaction discussions and can mitigate disruptive factors in the M&A process.

With regard to the selection and implementation of restructuring measures, including an M&A process, the general duties remain in force for the managers of the target company, including the applicability of the "business judgement rule." However, an additional set of duties arises during the preparation and execution of an M&A transaction in the StaRUG-scheme. Management must adapt its actions since the necessary weighing of interests shifts more in favour of creditor interests as the crisis deepens.

Ultimately, the new StaRUG procedure offers significant advantages in distressed M&A situations, not only as compared to an out of court acquisition, but also compared to a distressed transaction in a traditional German insolvency proceeding. Preservation of value is likely to be significantly enhanced as a result of the new StaRUG process.

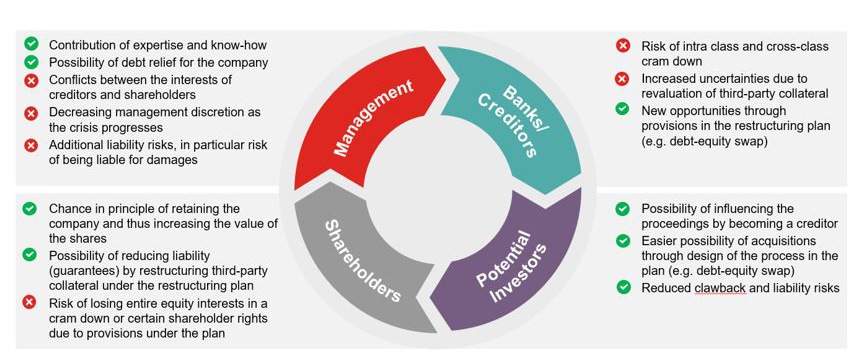

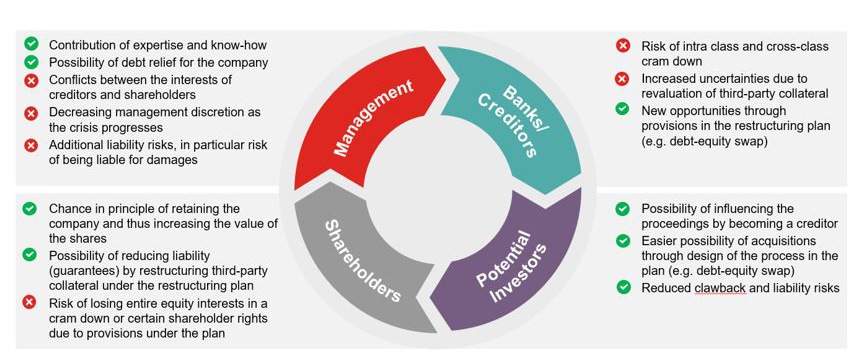

Advantages and disadvantages of the StaRUG-scheme for the individual M&A stakeholders

In the preparation and implementation of a restructuring pursuant to the StaRUG-scheme, the interests of the main acting parties in an M&A process are impacted differently.

Management

Similar to a self-administration procedure, management of the company benefits from the contribution of its own know-how, which allows it to respond in the best possible way to the needs of the distressed company. In addition, the StaRUG-scheme opens up the possibility of de-leveraging the company without the consent of all creditors. However, once the StaRUG restructuring matter has been notified to the court, management is exposed to additional liability risks as well as tension between creditor and shareholder interests. The restructuring must be aligned with the interests of creditors, which may also limit the discretion of management. This can give rise to considerable uncertainties for management. The need for solid legal support for management becomes clear and is critical.

Shareholders

The StaRUG procedure offers various potential advantages for the company's shareholders. As a result of the ability to achieve debt relief and further restructuring measures, the possibility of preserving the going concern value of the company is enhanced, which in turn can increase the value of the shares. In addition, liabilities of the shareholders due to guarantees can be significantly reduced through the restructuring of intracompany third-party obligations. However, there certainly are disadvantages to shareholders including the potential for restriction of shareholder rights contained in the restructuring plan or at worst the loss of their equity interests entirely as part of a cross-class cram down.

Investors/acquirors

Investors or acquirors are able to have a direct impact on the course of StaRUG proceedings and thus on the structure of the entire transaction by way of an acquisition of claims. By means of a debt-equity swap, they would have the opportunity to obtain an equity position against the will of certain subordinate creditors or minority shareholders. As part of the restructuring plan, existing financing and collateral could also be restructured in a simplified way. Further advantages include the reduced risks of insolvency clawback and liability (discussed below) if the transaction is structured appropriately.

In addition, M&A transactions outside of the traditional insolvency proceedings offer the advantage of avoiding reputational damage, both for the investor and the company.

Stakeholder analysis in the context of StaRUG

Clawback and liability privileges for new financings

The possibility of clawback or other liability regularly creates considerable uncertainty for the purchaser in a distressed out of court M&A transaction, as they are often unable to assess the extent to which the acquisition or simply new or interim financing in favor of the target company may be subject to clawback or liability risks in a subsequent insolvency case. This uncertainty may well last for several years, as the statute of limitations for a statutory clawback claim is three years and the possible subsequent insolvency administrator is not required to declare in advance that they will exercise the right of clawback. The StaRUG-scheme, however, offers new investors a "safe harbor" in principle with corresponding privileges under StaRUG Sections 89, 90. Indeed, new financing – in the form of debt and/or equity – can be expressly included in the restructuring plan and is safe harbored from any clawback risk in the event of subsequent insolvency proceeding.

Safe harbour during the pendency of the restructuring case

As a rule, a clawback claim under German insolvency law not only requires that creditors were disadvantaged by the transaction, but further specific requirements, including the knowledge of the opposing party (in this case the investor) of the debtor's illiquidity, the debtor's intent to disadvantage creditors and the knowledge of such intent on the part of the opposing party. Whether a transaction caused a creditor disadvantage is difficult to assess in complex and multi-part M&A transactions. Clearly, a disadvantage can result from the lack of adequacy of the purchase price and the resulting reduction in the value debtor's assets. Further, creditor disadvantage may exist if a transaction alone has made it more difficult for creditors to gain access to the company's assets and enforce their obligations.

The StaRUG restricts the scope of application of the so-called actual intent clawback (Vorsatzanfechtung). Thus, pursuant to StaRUG Section 89, an act cannot be found to be taken with intent to disadvantage creditors solely based on the fact that a party to the legal act had knowledge of the pendency of the StaRUG restructuring case or the use of StaRUG proceedings or instruments.

Thus far, however, the question remains unclear as to whether a mere interim financing for the purpose of preparing for a possible transaction under StaRUG, e.g. a bridge loan, falls within the protection of the safe harbor.

Privileges in the case of acts in execution of the plan

In addition, pursuant to StaRUG Sec. 90, the provisions of a legally confirmed restructuring plan and acts performed in execution of such a plan are only open to clawback if the confirmation of the plan was based on incorrect or incomplete information provided by the debtor and the investor was aware of this incomplete or incorrect information. This restriction on clawback claims does not apply to subordinated claims (nachrangige Forderungen) or securities of the shareholders themselves. The aim is to address the risk that the plan will fail contrary to expectations. The restriction is therefore limited to the period until sustainable restructuring (nachhaltige Restrukturierung) is achieved. The requirement of sustainability refers to the implementation of the plan. Consequently, the creditors or new creditors included in the plan do not benefit from any further protection against a clawback if insolvency occurs later for other reasons.

There are some uncertainties in the StaRUG-scheme, such as the definition of "sustainable restructuring" (nachhaltige Restrukturierung), which may pose challenges for the contracting parties. Further questions are also likely to arise with regard to the relevant clawback period. The examination of possible insolvency clawbacks remains a case-by-case decision by the bankruptcy official. It also remains to be seen to what extent future case law will require the submission of a so-called restructuring opinion (Sanierungsgutachten IDW S6) as evidence of the knowledge of the possible intent to disadvantage creditors in M&A transactions in the context of StaRUG proceedings. This would certainly not be conducive to StaRUG transactions as an IDW S6 expert opinion has higher requirements than StaRUG and also results in a time delay as well as further costs.

Although there are some challenges as outlined above, in principle the court-confirmed restructuring plan under the StaRUG-scheme can be used as a safe harbor for new debtor or equity financings, e.g. in the context of an M&A process. The possibility of clawbacks is made significantly more difficult. It can be assumed that this will have a positive effect on the willingness of any investors to buy.

Summary

The various advantages of an acquisition in the context of a StaRUG-scheme explained above clearly outweigh the possible risks. In particular, the ability to better preserve the value of the company while avoiding the stigma of insolvency and/or the possibility of acquiring the equity outside of a formal insolvency proceeding over the objections of individual/all creditors and shareholders is a powerful tool for both the company and the new investor or acquiror.

Although there currently are some untested areas in the interpretation of the law, particularly with regard to liability and clawback claims, we predict that many distressed companies will nevertheless go down the path of a StaRUG-scheme in connection with an M&A transaction and attempt to solve any potential challenges or disadvantages with the legal instruments available. In any case, future developments under StaRUG remain exciting.