In search of joy

Say it in a postcard | Issue 20 | 2022

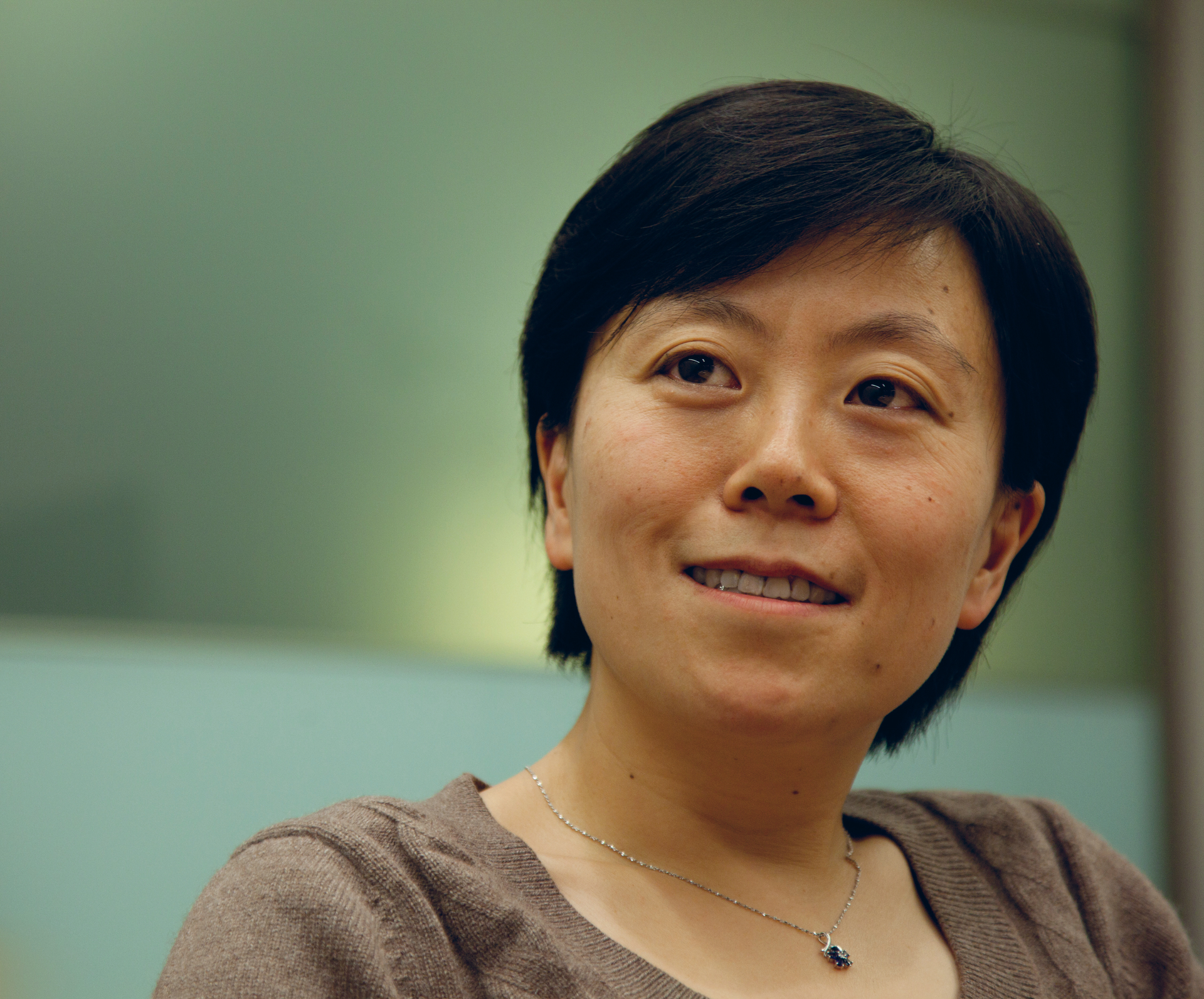

Wang Yi in conversation with Ingeborg Alexander in 2011

I was born in China in 1972, during the Cultural Revolution.

I went to primary school very young, I think I was five. In China you generally start at seven.

If you can pass the test, no matter how young you are you can go to school. I passed. And why, because my auntie broke her leg and stayed at home for three months, so she spent the whole time teaching me Chinese and mathematics.

When I was a teenager I always liked ancient history. I used to write in classical Chinese.

My son is thirteen. He has just started showing an interest in history. Before that, my husband and I were slightly concerned that his generation don’t have a dream …they spend too much time on cartoons, TVs, electronic games and they don’t care about history or the future or people around them, they just do what they like to do. At his age he should be interested in more serious things like culture, music, of course his study for sure, art, politics.

Compared to my childhood I think my son’s childhood was more boring.

My parents are zhishifenzi (intellectuals). My father graduated in 1965. His father was Guomindang (KMT); my mother’s family was also Guomindang – so for a long time their family background was not good.

My mother’s father had a chance to go to Taiwan but he stayed here. He just didn’t want to leave his home town. Very simple. That’s it. So he decided to stay; and this changed his life, and his family life, and his children’s life.

My father was lucky; he got into university because he chose a petroleum university. This university didn’t pay too much attention to family background because they couldn’t get hold of enough students.

My mother didn’t have this chance. And she even didn’t know why she failed. Nobody told her. She studied Russian at school and got 99 out of 100 in the admission test. And yet she didn’t get into university and nobody explained why.

University graduates during the 1960s were very precious.

My mother I think felt sad about this throughout her entire life. That’s why she wanted me and my sister to go to university. To realise her dreams.

My parents-in-law had a very different life. In their family they were all gongren (workers). In China, the workers were the ruling class for a long time, so after the 1980s, and China’s opening to the world, when the status of intellectuals started going up while workers and farmers were going down, they felt a bit lost.

In China, we had always thought that only physics, chemistry and mathematics were important subjects for children to study. Now it’s changed. My husband graduated from Beijing University of Technology but he says that he won’t force our son to study technology; of course, I have never thought my son will read law. He does not need to learn in order to make money, so he can choose something he is really interested in.

I became a lawyer by chance. Not by mistake but out of my intention or expectation.

My law school, the China University of Political Science and Law, is one of the very best in China and the only one under the direct supervision of the Ministry of Justice. When I went there, in 1990, the university only took 400 students a year so there were only about 1600 in the whole school.

We didn’t choose it at all. I was taken by fate.

I think, like most Chinese children, we don’t think the study when we are young is just for ourselves; to a certain extent it’s for our parents. So when I had finished my admission test, I thought my job was done; which university I would go to didn’t matter too much. I left it to my parents to choose.

My parents took three days off to study the previous admission rates for different universities and they chose nine universities at three different levels, each with three majors, and then all ranked in priority. They put foreign languages as the top priority.

They didn’t even apply to my university.

That year there were 22 places available at my university for students from Sichuan province. But only eight applied for my university and did well enough to get in. That’s how I got an offer. You can say on the form if you are okay about being moved to other universities in the same subject area and my parents had done that. And I had high scores in the test, so I was ‘upgraded’.

When I got the admission notice, I didn’t even know where the university was. Then we checked the envelope and saw it was from Beijing.

When I gave my parents entire authority to apply for me, I only raised one issue: I didn’t want to stay in Chengdu. I wanted to be independent.

Most Chinese children are ruled by their parents for years, until they go to university; even then, if you live in the same city, you are still under their control and you have to go home every weekend and tell them everything.

I said no, I don’t want to go to university in Chengdu, although it’s a nice city, my home town, I like it; but I want to be outside.

My university was in north-west Beijing, in Haidian, where all the old, prestigious universities are. But, when I got off the train, I was taken to Changping county to the north, along the Badaling highway, to the new campus. And they hadn’t told us at all, you will be moved to that far, remote area. The bus kept driving for an hour. Changping twenty years ago was really under-developed, just fields and a very small town, no big buildings, no shopping malls. It was thirty-five kilometres out from the centre of Beijing, and the campus was still under construction. I was really disappointed.

I shared a small room, fifteen square metres, with five other girls, in bunk beds.

The old campus was for postgraduates and the new one was for law undergraduates. We fought to go back in the last year – jue shi – we refused to eat for three days. But we didn’t succeed.

I never felt I had enough money for the whole four years. I got some money from my parents, I had a subsidy from the university and I was a keen athlete so I got another subsidy, and I did relatively okay in my studies so I got a scholarship. I got all this but it was still not enough, because I like travelling. Every summer holiday I was wandering outside somewhere, but in the winter I always went home for Chinese New Year.

At that time students didn’t work in the holidays. I have a cousin in Guangzhou and it was different there (because Guangzhou is so close to Hong Kong) so she worked in a restaurant during Chinese New Year and made enough money to travel to Tibet. I was really jealous because I didn’t have that chance in Chengdu.

Big companies in China have their own school, kindergarten, canteen, hospital, everything. We call this ‘big company, small society’; you stay in the company from the time you are born until you go to university.

My father worked for the Sichuan branch of PetroChina. They provided accommodation; the more senior you were, the bigger the apartment you would get. So we moved from a one-bedroom to two bedrooms, then three bedrooms in the end.

I didn’t have a clear plan when I graduated (although I knew I didn’t want to work for a Chinese law firm). So I was allocated back to Sichuan. My father’s company took me. He arranged this for me. Because my father was working there, they were obliged to take me back if I wanted it.

I passed the Bar exam and qualified in 1995. In the whole of China, only 4,000 passed that year.

I got to know my husband after I graduated, and then I decided to marry him, and he was in Beijing, so I had to come to Beijing. Then I needed a job. But I had no hukou (residential card) and without a hukou you cannot get into a state-owned company or government body: I had to work in the private sector. So I had to go to a Chinese law firm.

I was assigned to a partner in the firm who was actually working for an American law firm which was waiting to get their license. That’s how I got to know there are foreign law firms in China. That’s fate again.

I joined Norton Rose in 2001. From then I felt sort of ‘clear water’. I quite liked the environment of this foreign law firm. I quite liked my work, although it was tough at the beginning, and I didn’t have any overseas educational background or living experience.

The culture is very different.

After I got married I did go to Tibet, in 2000. We had a big plan to start from Lhasa and go to other places but my husband had serious high altitude sickness, so we stayed in Lhasa for four days and had to cancel the rest of the trip.

At some point I want to study twentieth century history, especially China’s history. What we were taught in school is incomplete. I really want to know what we don’t know about what existed.

I don’t want to go back to school when I am 50 or 60. It’s too late. So I may retire early.

Columbia University in New York seems well known for Oriental history research.

I didn’t agree with the one-child policy. I decided not to have a second one just because I feel it takes so much energy and time to bring a child up, and I need to work hard, particularly in my industry, there’s never enough time to be with your child and if I had two I can’t imagine how I could manage.

Sometimes I feel sad that I don’t have a daughter; one boy, one girl is perfect. But I think you need to have some sadness during your life. I haven’t experienced any big difficulties in mine: yi fan feng shun (smoothly). There’s a Chinese saying: 月盈则亏,水满则溢. Don’t expect everything to be perfect; it’s good to have some problems in your life, otherwise bad fortune may strike.

Wang Yi: born Chengdu 1972; LLB (Zhengfa Daxue) 1994; joined Norton Rose 2001; partner, 2009

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025