Publication

Corporate self-reporting: Weighing the cost of coming clean

Multinational businesses face a series of complex issues when evaluating whether to self-report economic and financial crimes such as bribery, fraud and corruption.

Global | Publication | October 2016

It is a promising time for Mexican renewables. After the energy sector was monopolised by the state electricity company CFE, limiting private participation for more than 75 years, a much awaited constitutional reform law was approved in December 2013 which will liberalise the sector for private investment and transform the power sector into a competitive wholesale market. A comprehensive package of 21 secondary laws were then enacted in August 2014. Accordingly, overall investment in the sector rose in 2014 to US$2.4 billion, as reported by the US International Trade Administration.

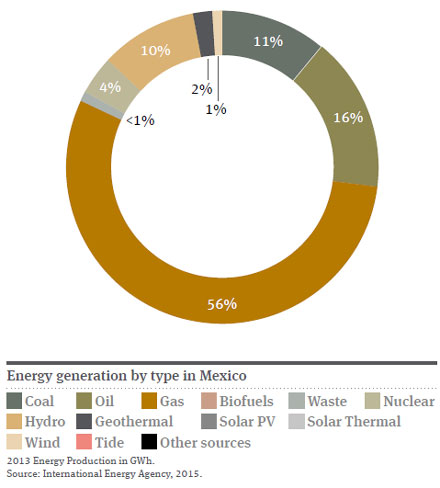

The main instrument governing the renewable energy sector in Mexico is the Law for the Development of Renewable Energy and Energy Transition Financing (LAERFTE), enacted in 2008. Under this law, Mexico implemented the Estrategia Nacional de Energía 2013–2027, which establishes that 35 per cent of energy should derive from renewable sources by 2024 (i.e. wind, solar, mini hydro, biomass, geothermal and wave power, large hydroelectric plants and, more controversially, nuclear energy).

According to the Mexico Energy & Sustainability Review 2014, Mexico accounts for 1.6 per cent of the total worldwide greenhouse emissions. This makes it the thirteenth largest emitter worldwide. Mexico’s geography makes it vulnerable to certain effects of climate change, for example, droughts and decreasing precipitation rates. Facing this reality, the General Climate Change Law set a goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent by 2020 and 50 per cent by 2050. The US International Trade Administration ranks Mexico fifth on its list of top renewable energy export destinations for 2016, with opportunities projected in every subsector.

The government provides project finance for renewable projects through its development bank (Nacional Financiera), using financial resources contributed by IFI’s (IDB, IFC – World Bank, German Development Bank etc). Local players, including financial institutions, utilities and corporations, put around US$915 million into Mexican clean energy assets in 2012.

Mexico has rich solar resources and is located in the socalled Solar Belt. In the Baja California region, average solar irradiation is greater than 2,200 kWh/m² per year which, to put in perspective, is more than double the radiation in Germany. Across Mexico, daily radiation varies between 1,600–2,250 kWh/m² per year, which is comparable to some of the best locations in the world such as the MENA region and Chile. The first large (30MW) solar PV plant, Aura Solar I, started operations in 2013 in Baja California. In August 2015, the country’s solar energy association, ANES, announced its target of 3GW total installed capacity by 2025.

Mexico has traditionally been one of the largest geothermal markets in the world, yet little development has occurred over the past decade. Recently, interest in the sector has revived with the development of two new 50MW projects. Geothermal research centre CEMIE-Geo opened in 2014 with an operating budget of US$75 million over the next four years to promote exploration and projects within the private sector. Geothermal has the advantage of providing baseload power, unlike the intermittent nature of solar and wind, which makes it attractive for developers and investors. In July 2015, the Ministry of Energy awarded five geothermal concessions and 13 permits for exploration to CFE, who will study geothermal resources for 448MW capacity across three states.

Currently, there are no private owners of geothermal power plants and the only plants in operation are owned by the CFE. However, Deputy Planning Minister Leonardo Beltran stated in July 2015 that private investors will have the opportunity to develop some 5000MW of probable geothermal resource in the country. The Energy Ministry expects an additional 217MW of geothermal power by 2018. This number is modest compared to the estimates for wind and solar, but reflects the greater time and resources needed for geothermal projects — a typical project takes about seven years to complete. The secondary law, which is solely focused on geothermal energy, will prove key to giving this energy source the necessary boost by addressing the high risks and costs associated with geothermal exploration.

At the end of 2015, the national installed capacity of wind energy was 3,037MW. The Mexican Wind Energy Association, AMDEE, has targets to generate 12GW of power by 2020. Construction has mainly been focused in Oaxaca, considered to be one of the best wind resources in the world, but investment has slowed down due to a mixture of social conflict with communities and a saturation of projects. Nevertheless, Enel Green Power is currently constructing an additional wind farm in Oaxaca having completed its Sureste I – Phase II farm in March 2015, and Iberdrola continues to construct its 102MW La Ventosa plant. Gamesa finalised an agreement with Banco Santander in 2014 for the joint development of wind farms in Baja California, with a total installed capacity of up to 500MW. In 2016, there is expected to be 805MW of new wind capacity added to the grid, rising to a total installed capacity of 9,500MW by 2018.

According to AMDEE figures, investments in Mexican wind to date exceed US$6,000 million. This reflects the 37 wind farms of varying sizes now in operation in the country. Between 2016 and 2018, a further US$13,000 million of wind investment is expected.

Mexico expects the largest chunk of new solar and wind capacity to be generated by businesses, which under the self-supply law allows companies to buy electricity directly from power plants. Walmart, for example, supplies its stores in Mexico from a 67MW wind farm in Oaxaca. In May 2014, a 252MW wind project was announced in the state of Nuevo Leon that will provide energy for a group of companies including FEMSA and cement giant Cemex.

Mexico has several schemes for development of renewable energy generation, including the small power producer, self- supply, co-generation and the IPP schemes. The aforementioned law reforms included the set-up of a clean energy certification scheme to serve as the primary mechanism for encouraging clean energy development.

This certification scheme sets a target for all suppliers and qualified users of the grid to source five per cent of all energy generation from renewable sources.

Tax incentives are established under Article 40 of the Law of Corporate Income Tax, among others, which provides for accelerated depreciation of 100 per cent for investments in equipment and machinery for electricity generation through renewable sources. The condition is that the equipment/ machinery must remain in operation for at least five years following the tax deduction declaration. Further incentives include an exemption from import and export tax and a tax credit.

A funding mechanism was set up under the auspices of the Fund for the Energy Transition and Sustainable Electricity Use (LAERFTE). It invests in studies which further the objectives of LAERFTE. The fund is destined for research institutions and excludes private companies. It offers resources of US$538 million and is expected to be a fundamental player in helping Mexico reach its targets. Furthermore, the Mexican development bank, NAFINSA, is committed to supporting the government’s renewable energy ambitions – it financed 50 per cent of the capital for Aura Solar I, the first large scale PV plant in Mexico.

Regulations allow for the excess energy produced from renewable sources to be stored (banked) by CFE, so that it can be later used or sold to the CFE at a discounted cost.

Reliable transmission and distribution infrastructure is essential for most intermittent electricity generation projects. Frequently, substations located in areas which offer a high concentration of resources, such as the Tehuantepec and Isthmus regions, do not have capacity to handle proposed projects or there are no transmission lines available to transport electricity to consumption centres. Historically, the CFE was the sole entity authorised to construct and operate energy transmission and distribution infrastructure. There were many complaints about the slow speed at which it upgraded and expanded the grid. The energy reform law now allows private sector participation in the development and construction of transmission lines, with CFE remaining as the grid planner. The private sector might well become a key driver for the development of the network.

As in other Latin American countries, obtaining finance remains a challenge. In particular, financial institutions are hesitant to provide funding to companies lacking AAA credit ratings. To meet the renewables target, smaller offtakers need to be able to access the self-supply scheme (and this is a trend which has been successful in the US to some extent). One solution is pooling several small offtakers; this was successfully tried by Next Energy, which brought together seven municipalities to build a 22.5MW wind farm in Monterrey.

There is significant resistance from local communities to allowing land acquisition for renewable energy projects or transmission lines. Last year, riots occurred in Oaxaca, where indigenous communities challenged the development of the Mareña Renovables Wind Farm on their lands, because they signed a contract based on incomplete information. As a result, the project has been frozen for over two years. The government still has some work to do in developing community R&R and information sharing.

According to the Mexico Energy & Sustainability Review 2014, investments in the renewables sector have grown over 92 per cent in the last five years and installed renewable capacity is likely to grow ten per cent annually in the upcoming years. SENER expects renewable energy capacity to be driven primarily by wind power, which it states could account for 60.3 per cent of the national energy mix by 2025. The next largest contributors are expected to be small hydropower with 24.3 per cent and solar energy with a 12 per cent contribution.

Multinational developers and equipment suppliers have flocked to Mexico due to its opportunities and reliability. Several domestic companies have also penetrated this market with diversification into small-scale projects and equipment manufacturing. This is also reflective of trends in South Africa and India, where local manufacturing is evolving hand in hand with renewable energy project development.

Publication

Multinational businesses face a series of complex issues when evaluating whether to self-report economic and financial crimes such as bribery, fraud and corruption.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright US LLP 2025