Way of life

The birth of Raphael | Issue 17 | 2020

Love set you going like a fat gold watch.

The midwife slapped your footsoles, and your bald cry

Took its place among the elements.

from Morning Song

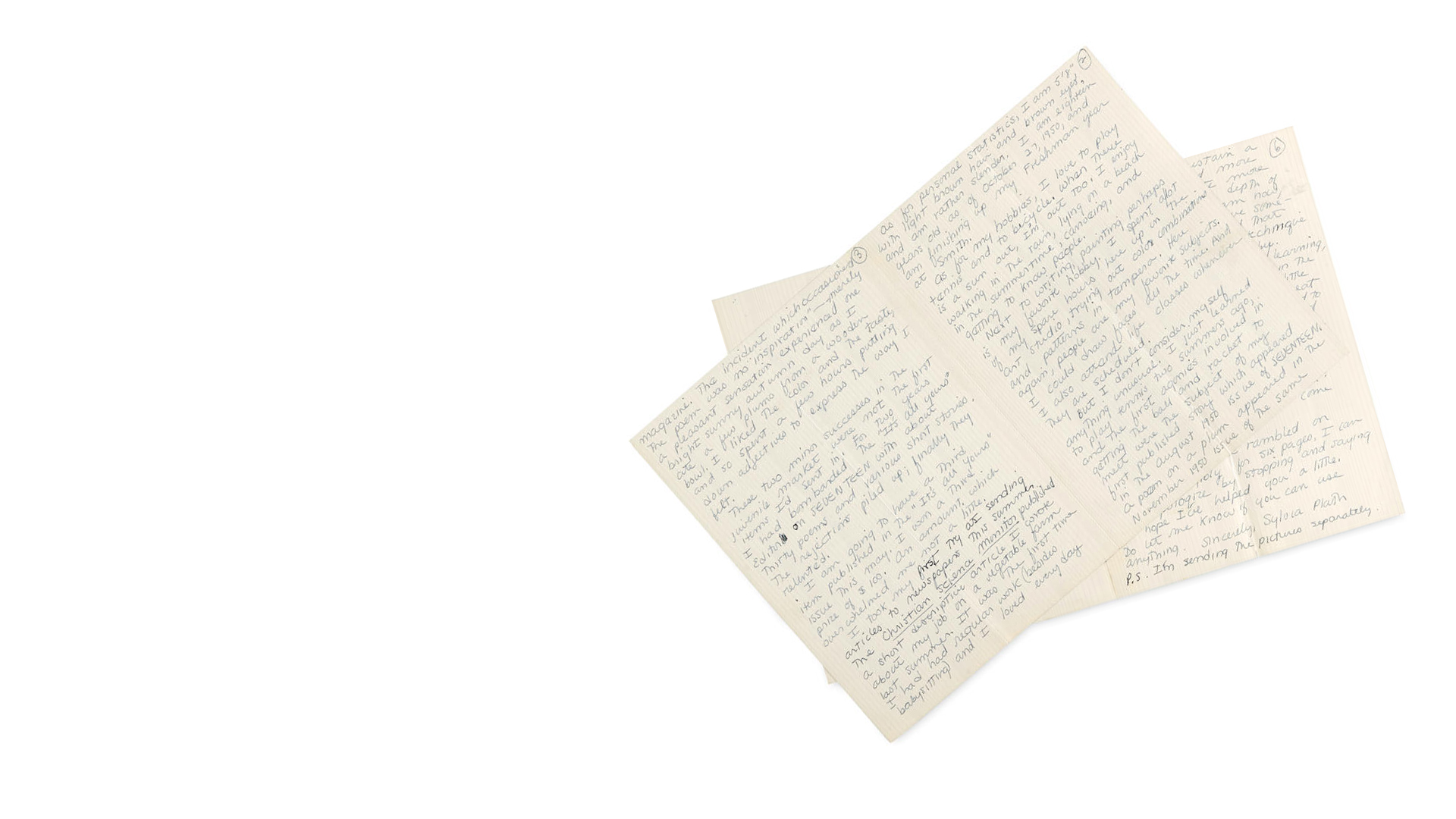

There is a recording of an interview with Sylvia Plath, originally broadcast on BBC radio in October 1962. It took place a few days after her thirtieth birthday, and coincided with a period of feverish creativity for Plath. “I am writing the best poems of my life,” she said at the time, in a letter to her mother in Massachusetts. “They will make my name.” At Plath’s home in rural Devon, in the thatched house she had bought with her English husband, the poet Ted Hughes, she rose before dawn and worked until her children awoke. It was the only time she could find to write. And the poems poured out, sometimes several in a day, in a white heat of inspiration.

I think you can hear something of the exhilaration in her voice. She speaks fast and with an undercurrent of breathlessness. Her accent is fascinating; it seems to straddle the Atlantic, suspended somewhere in between American and English. Her vowels are long and round, her consonants fastidiously pronounced. The writer Elizabeth Hardwick described it as ‘Englishy’: Plath projected “full-throated, plump, diction-perfect, Englishy, mesmerizing cadences”. She seems to enjoy the texture of language, rolling each word around in her mouth like something delicious.

This quality seems to infiltrate her poems. In particular, I find myself, in the weeks and months after the birth of my son, thinking again and again of Plath’s poem Morning Song, written in 1961. I savour the images: the mother stumbling from bed, “cow-heavy”, at her child’s cry; the baby’s “moth-breath” flickering among flat, pink roses; its open mouth, “clean as a cat’s”. I have always liked the way these phrases sound. Now, held up to the flame of experience as a new mother, a close observer of babies, they seem even brighter, even sharper.

Plath is asked in the interview whether she designs her poems to be read aloud. “I’ve got to say them,” she says. “I speak them to myself.” She sounds so urgent, so full of life, it is difficult to believe that less than four months later she was dead, committing suicide by gassing herself with carbon monoxide fumes from her kitchen oven.

It is tempting, if you look at Plath’s work through the lens of her tragic biography, to read her poetry as a sort of protracted suicide note. That is far too simplistic. When I think of Morning Song, when I read it aloud to myself, I hear an energy, an exuberance, that is rooted in life, not death.

Alexandra Howe is the arts editor of RE, currently on maternity leave in London

First published in RE issue 17 (2020)

© Norton Rose Fulbright US LLP 2025