Style

James Reid. Sacha de Klerk. Nicola Liu. Andrew Robinson. On the subject of shoes.| Issue 20 | 2022

Preface

This collection of essays by writers all over the world was put together in the first half of 2020. We asked our writers to explore what it is to be alive in the time of COVID-19 and gave them a certain freedom in how to frame their response—our only steer was to write either within a small and intimate frame or from a wide, sweeping perspective. What surprised us was the way in which each writer rose to their task with clarity of purpose and sent in something quite distinctive. RE: was founded in 2011 to celebrate diversity. This collection, commissioned to record a history of this time for Norton Rose Fulbright, is proof of that.

Contents

WANG YI

Community

STEFAN HAGNER

Letter from Texas

NATALIA MUSHINSKA

An indefinite time in Paradise

ATTILIO PAVONE

Without purpose

LAURA SHUMILOFF

Mourning

UGENDRAN ODAYAR

Levelling down

YUI OTA

Lockdown Day 67

KENNETH GRAY

Ayamonte

JAMES REID

All a bit abstract

JAKE BELL

Routine

ADITYA REBBAPRAGADA

Surfacing

SARAH XIONG

The mother

SHAMIM RAZAVI

Breathtaking

NICK GRANDAGE

Let it be

MATHIEU DAHAN

Cinema

NEIL CARRUTHERS

Letter from London

RUSS TRICE

A blessing

ALISON DEITZ

The prism of history

JARRET STEPHENS

Stolen time

Beijing

我在北京的两个家,一个在皇城根儿下,一个在东边郊外;前者属于东城朝内社区,后者属于朝阳黑庄户社区。疫情期间,社区里人烟稀少,所有酒廊食肆、商家店铺一律闭门谢客,有些甚至永久歇业,往日熟悉的市井烟火消失无踪。相反,我手机里那个虚拟社区,却生机勃勃、日益兴旺。社区成员天南海北、素昧平生,然志合者不以山海为远,道乖者不以咫尺为近。我喜欢看小区花开花落、聊邻居家长里短,也喜欢在云端笑谈天下、观世界风起云涌。我不知道更爱哪个社区,但我知道,从此,两个一个都不能少!

I have two homes in Beijing. One is at the foot of the Imperial City—in Chaonei, in the district of Dongcheng—and the other is on the eastern outskirts—in Heizhuanghu, in the district of Chaoyang. During this time of isolation, there are so few people to be seen anywhere. All the restaurants, bars and shops are closed, some permanently. The once familiar sense of a bustling neighbourhood has vanished. But the virtual community on my cell phone thrives. Members of this community live in all corners of China; some perhaps don’t know each other in person even though they are in the same compound. There is a saying in China: ‘People of like minds are not far away even when separated by far-away mountains and seas. People of unlike minds are not close even when within touching distance.’ At home, in isolation, I love to watch flowers as they blossom and fall, and to talk foolish talk with my neighbours. When I go to my virtual community, I love our many conversations about the ever-changing world in the cloud. I have no preference, one community over the other, but I know I cannot be parted from either.

Dallas

All we could do was to slow the spread and buy time. Because you cannot fix what is unfixable, we went through phases of lockdown, from ‘stay-at-home’ to ‘safer-at-home’ to ‘protect your neighbors’. Traveling to meetings was no longer possible and we started working remotely with our physical offices closed. We stayed indoors and, when we had to leave for grocery shopping, we put our masks on to keep others safe. We helped contain the spread. At the same time, entire industries came to a standstill and millions of people lost their jobs.

Ideological tensions over values emerged, one of them being health and well-being versus personal freedom. A few politicians suggested the elderly would be willing to sacrifice their health for the sake of the economy. Times of crisis bring out the best and worst in people, and our fundamental values were put to the test.

It didn’t end there. We were reminded that racial discrimination and injustice is not a relic from the past. Millions of people in the U.S. and around the globe spoke up—in a peaceful manner—against racism, against police brutality, and against inequality. No one can be above the law. We shall look back on the time of COVID-19 as a turning point. There is much to be done but I am hopeful for the future.

The pandemic inspired change; and reflection. My eleven-year-old son concluded that the world is trying to get rid of humans—pointing to the Coronavirus, wildfires and other natural disasters. I concluded that we have to do a better job protecting our planet for the generations to come. If we don’t act now, it will be too late. Global warming is a fact, not a belief.

The pandemic also reminded us that times of peace are not to be taken for granted. Nationalism and ‘divide and rule’ do not lead to stable, prosperous societies: history shows us this, time and again. We can only do well if everyone else does well.

Our entire neighborhood started howling in support for our healthcare workers at 8 pm every evening. These and all essential workers were the true heroes in the pandemic. Howling for them was fun and the least we could do. What else? Schools closed in the middle of March; the children I met did not seem to mind, not like the parents. And what else? In company with many others, we stayed in and watched movies. The Last Dance was a popular one, chronicling Michael Jordan’s last NBA season.

As a child, I was petrified about Chernobyl, the cloud with nuclear waste, the Cold War, life ending right then in 1985. Nothing is all black or all white, that’s the point I am trying to make. Don’t lose hope. Our patience and resilience will get us back on track.

Stay safe, and be kind

Stefan

Moscow

‘Welcome to the Swiss paradise!’, heartily exclaimed a Swiss neighbour when I arrived.

I should admit that from the very beginning my trip was not an ordinary one. I had to find a way to take my dog (my dog exceeds an airplane hand luggage limits). My sister and I came to the idea of travelling by car. She would fly to Moscow and we would drive together, taking turns, the two thousand five hundred kilometres from Moscow to Zofingen.

The plan was that I would stay in this quiet little city for the whole of my two-month sabbatical. The idea in my mind was to switch off from the endless office routine and city rush and spend time with my sister and three beloved little nephews. This was at the end of February 2020. At that time there was little evidence of the forthcoming pandemic and the lockdown.

Then the Swiss started to avoid shaking hands (a feature of their culture that used to give me such excitement—in Russia, a woman would never be offered a handshake, not unless she were a high-ranking official; Coronavirus has swept away this wonderful habit of the Swiss, and who knows whether it will ever come back).

So, yes, at the end of February there were uncertainties, many, but people seemed inclined to the idea of the danger being exaggerated. The whole thing was being overstated by the governments and the media, that’s what they were saying. I kept asking—in Switzerland and among my friends in Russia—whether they knew of anyone who was seriously ill. No one was affected, not then.

But the situation developed. Russia closed its borders on 30 March and the Swiss paradise became a continuous reality for me. How does it feel when you are placed in a kind of perfect environment and you can perceive the lifestyle of your dreams? When you do not have to confront aggression or struggle with everyday disruptions? ‘It feels really good’, is the answer to my Russian friends who claim that difficulties make people stronger and prompt creativity. Not at all! When you face every day stupidity, injustice and indifference, you lose your energy for anger and become a part of it. This is a destructive process that only a few of us could resist.

Eventually, I had to face the fact that I was locked in Switzerland for an uncertain period of time. Hospitals were made ready to receive high numbers of patients, the country was closed for quarantine, and the government allocated CHF50 billion to support the economy.

At some point in May I started receiving bad news from Moscow. Most of it was about doctors. My relatives and friends who are in the medical sector kept telling me about doctors being severely ill. At the beginning of June, when the number of cases in Russia hit its maximum, the Mayor of Moscow suddenly removed the quarantine restrictions and changed the whole regime back to normal. The Russian media became more focused on the Victory Parade, scheduled for 24 June, and the national vote over amendments to the Russian Constitution, planned for 1 July. When something is done in contradiction to common sense it makes me really scared. As I write this, there is still no clarity. My journey back, another two thousand five hundred kilometres, lies ahead, and who knows what the future holds. I don’t.

Milan

What did I miss most during lockdown? Walking.

Here in Italy, the hardest stage of the restrictions required us to justify movement of any kind. In a land where bureaucracy never dies, the government issued, week after week, more and more complicated self-declaration templates. We were asked to state exactly where we were going, why (there were fixed options to tick), and from where. Laying aside the silly disputes involving the legitimacy of jogging or taking your child out (within 200 metres from home was, it seemed, allowed, and this did at least set on an equal footing the rights of children and dogs)—for two months, a simple walk without any purpose to it put Italians at risk of being heavily fined.

Yes, I could see the point of the restriction—and I am happy to see that the ‘stay at home’ strategy eventually worked—but I never accepted it entirely. My professional lens made me focus immediately on an unacceptable limiting of constitutional rights, but I have to admit that, at least in the short term, public health is one of the few limits entitled to curtail freedom of movement. So, instead of drafting an arbitrary application to the European Court of Human Rights, I bought a treadmill. This was good for my health and for keeping myself in shape, but it could not replicate the effect that a real walk has on my mind.

For me, walking cleanses my brain. I don’t know if it can be compared to meditation, but it definitely alters my state of mind. The light physical activity takes all my daily concerns and simply removes them. It opens a path into daydreaming.

During lockdown, I missed wandering in the wilderness. I found myself retracing the mountain paths I have walked in the Mont Blanc area, with the help of guide books and Google maps. I thought about the paths I still wish to explore. I mourned the chances of (safely) getting lost. Franco Michieli writes that “the mysterious beauty of a landscape does not come from its look and power, but from the infinite stories that can happen there, involving us”. I wanted to be part of those stories. I wanted the means to walk relying (prudently) on “the subtle magnetism in Nature, which, if we unconsciously yield to it, will”, according to Thoreau, “direct us aright”.

It need not be the wilderness. The city offers countless ways of walking with or without a specific destination. There is an almost untranslatable French verb, flâner, superbly described by Baudelaire as “walking with curiosity and laziness at the same time” (but it is much more than that). “To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world.” This was how Baudelaire spoke of it in Le Figaro all those years ago.

It has been difficult for me to do without my occasional strolls through the centre of Milan, changing direction many times without purpose, just for the sake of it. But I had one privilege during lockdown. As a separated parent, I am entitled to see my ten-year-old son on certain days of the week. These were the few times I had a ‘permission by law’ to walk in the streets. I found I could improvise convoluted routes from home to home.

In the empty streets of a deserted city, held in a complete and unreal silence, it was possible to notice what normally gets lost in the fast-paced flow of the city—a glimpse of a secret garden, an old man listening to opera from a window on the ground floor, the sound of our own footsteps… . I enjoyed the pleasure of owning the city of Milan with my son. Emilio goes always ahead of me, sometimes dashing in short runs, as if he wants to explore. When he takes a way that is not in line with my own (often improvised) plans, I call him back. The smile I catch from behind his face mask makes me feel that everything will be better.

Reading about walking

Theory of Walking (Honoré de Balzac), 1st edn 1833

The Painter of Modern Life (Charles Baudelaire), Da Capo, 1964; Le Figaro, 1863

Walking (Thomas Bernhard), 2015

Perdersi a Roma: guida insolita e sentimentale (Roberto Carvelli), 2004

The uncommercial traveller (Charles Dickens), 1st edn 1861

A philosophy of walking (Frédéric Gros), 2014

Walking in Berlin: a flaneur in the capital (Franz Hessel), 2016, 1st edn 1929

Walking, one step at a time (Erling Kagge), 2019

La vocazione di perdersi (Franco Michieli), 2015

Wanderlust: a history of walking (Rebecca Solnit), 2014

Walking (Henry David Thoreau), 1st edn 1862, The Atlantic Monthly

The Walk (Robert Walser), 1st edn 1917

London

And so it came to be that, on a mid-morning in early April, I was one of five mourners at the funeral in a London suburb of a dear friend; a man of high reputation who had, somewhat against the odds, achieved a life span of three score years. In normal times, there would have been tenfold that number of mourners, but COVID-19 fears—together with the promise of a memorial service in the future—had, entirely understandably, kept people away in fear of their own lives and those of their loved ones.

By tradition it should have been a dank and drizzly day. The day was, in fact, a sunny and even hot one. The five mourners had not seen each other for some time, which would normally have resulted in enthusiastic conversations and hugs and kisses. As it was, COVID-19 regulations meant that they were obliged to meet in the crematorium’s car park—which was, helpfully, empty, so that each mourner was able to observe compliance with social distancing rules and occupy a demarcated car space, rather like a chess board. The mourners eyed each other uncertainly from the relative safety of their individual hatched car park space, not quite sure what acceptable funeral etiquette was at this time, and shouting brief greetings to one another. There should have been a distinctive floral tribute for the coffin. There was not. Thankfully, one of them had remembered to bring a single white rose to put on the coffin. Everyone else, myself included, had been so pre-occupied by the stress of getting to the funeral that they had forgotten to bring anything else but themselves to the occasion.

The ceremony itself was defiantly homespun. No celebrant—just a short speech by the chief mourner, who also operated the three pieces of allotted music. This departure from the norm was markedly at odds with the traditionally garbed pallbearers who, with impeccable manners, placed the coffin on the plinth and executed a perfectly synchronised nod of respect to the coffin before retreating from the chapel.

And so, twenty minutes after entering the chapel, the mourners filed out— maintaining a two-metre distance between each other—into the bright sunshine and resumed their positions in their respective hatched car park spaces. There were no tears, no hugs, no kisses and certainly no wake; just shouted sympathies from their places of safety and a swift move to the sanctuaries of their vehicles and departure home.

My journey to the funeral had been a relatively short and easy one, particularly at that time when most people were adhering to the instruction to make only essential trips, and there was little traffic on the road. I wanted to get home and have a quiet weep. Instead, I arrived, in less than an hour, strangely discombobulated and desperately craving sleep. I did not have the strength to weep.

I take comfort from my belief that my fellow mourners and I will meet again, hopefully at a raucous memorial service, where we will mourn properly and traditionally; that is, cry, hug and kiss each other, all whilst drinking toasts to the memory of the dearly departed, who truly was one of a kind, and the most generous man that I ever knew.

Durban

When will this end? Is it safe to go out?

I have been married for more than three years and our weekends are always spent visiting family, particularly our grandparents. This came to a grinding halt with COVID-19 and level 5 lockdown. I am so fortunate that all of my grandparents are still able-bodied and of good health. My grandads are 98 and 92. My grandmas are 91 and 85. We had a very real fear of infecting them. Visits were replaced with phone calls and inevitably: ‘When are you coming to visit?’ Six weeks went by like this. As the lockdown began to ease, we were able to visit—for a short while and whilst maintaining social distance. My beloved elderly grandparents understood that the virus was a problem, but I could sense that they were upset that we were not able to spend the usual time with them.

I have not been to the office in three months and I have no intention of going in anytime soon. It’s quite obvious why. But I am a very sociable person and I miss my colleagues! We have regular Skype-calls but I would so much prefer to be in physical contact with as many people as I possibly can be! I am getting the hang of working remotely. I set boundaries. I define work and play time. I am slowly adjusting.

Shopping has changed. We now do almost all our grocery shopping online, not something traditionally so popular in South Africa. It took a while for us (and the shops) to get used to this but it has really improved and it feels good to experience what we usually only see and hear about on TV. Where we do have to go out to the shops, our routine is to cover our skin as much as possible, sanitise as much as possible and shower the minute we get home, throw the clothes straight in the wash.

We are down to level 3 now. I am concerned about the continuing risk of infections. Are we making the right decision easing the restrictions? Is it safe to go out? When shall we be able to spend time with family like we used to?

London

28 May 2020, Lockdown Day 67

I wake to the strum of my 7.00am alarm, the light pours in as I draw back the curtains, and I take a drink. I open the COVID Symptom Study mobile app and confirm that ‘I feel physically normal’.

At 7.45am, I go for a run and allow thoughts for the day to flow through my mind as I wind around empty London streets accompanied by only the steady rhythm of footfall on pavement.

What do I need to do today? Is there enough food in the refrigerator? Do I need to go to a store because something is not available on Amazon? What can I do today? Can I go to the café next door for takeaway and still feel safe? Will there be a large crowd on the streets?

Back from the run at 8.30am, I make myself porridge and a cup of tea. I open the window and the rush of wind carries a fresh scent of grass reminding me of days spent exploring this new green and pleasant land I now call home. I sit on the window sill and look at the River Thames flowing slowly by, the low tide lapping at the shore, its surface glittering like a thousand tiny stars under the cloudless sky. I notice with a surprise a solitary plane in the sky.

When was the last time that I looked at the world map on the wall with colour-coded pins and thought about where I want to travel next?

When was the last time that I called a friend with whom I have been wanting to catch up to schedule a brunch?

When was the last time that I scrolled the Time Out London Instagram account to check which restaurants I want to visit?

My watch tells me that it is 9.15am. I go into the dining area, now my home office for more than two months, and enter the username and password on the computer.

29 May 2020, Lockdown Day 68

I wake to the strum of my 7.00am alarm, the light pours in as I draw back the curtains, and I take a drink. I open the COVID Symptom Study mobile app and confirm that ‘I feel physically normal’…

London

I am living in Ayamonte, a traditional Andalusian white village perched right on the south-western corner of Spain. It is surrounded by water: the Atlantic Ocean to the south, the Guadiana river, delineating the border with Portugal, to the west, and a mosaic of creeks and rivulets carving up the marshlands to the east. It has a long seafaring tradition—the area calls itself the cradle of America: it is from here that Columbus set sail in 1492. Rather less momentously, fishing and smuggling have long been, and remain, dominant industries.

Ayamonte has a distinct character to many other Andalusian villages. Perhaps it is its remoteness, perhaps its maritime traditions, perhaps its being a border town. The Ayamontinos are renowned for their openness and tolerance. The village has a large and integrated foreign community: there have been Portuguese, German, French, English and Dominican families, even Catalans, living in our small street of ten houses since we moved in. It has an (admittedly sparsely attended) annual Gay Pride. But the truth is that, however romantic the maritime and smuggling industries might seem, and however much it might bask in its particular reputation, the village lives from tourism. And, every year, from Easter onwards, other Spaniards descend from every corner of the country to enjoy the ham and gambas for which the area is famous.

The relationship between Andalusians and other Spaniards has always been ambiguous. There is a clichéd, commonly held view of Andalusians as ill-educated, lazy chancers, always on the lookout for easy money, the owners of a comic rustic accent. Too prone to bask in flamenco and bullfighting, to boast endlessly about Velasquez, Murillo and Picasso over perpetually refilled glasses of fino. Workshy. Poor. So the openness and warmth of the Ayamontinos is tinged by a certain resentment at being patronised.

The COVID virus hit Madrid and the north of Spain particularly hard and, in the middle of March, the Government proclaimed a State of Alarm and a severe lockdown. The geographical isolation of Ayamonte, the sparseness of the surrounding population and decades of under-investment in public transport made it a safe place to be—even the virus cannot find its way here, my neighbours joked. Understandably, those living in the larger cities with second homes wanted to leave whenever they could and the lockdown was very rapidly accelerated to prevent this. The beaches were closed: those who made it here found themselves trapped in their hot and airless apartments until they were sent back to their primary residences.

The fear of outsiders bringing the virus to the village destroyed the fine balance between openness and distrust amongst the local population. The local social media pages were full of unverified stories of Madrileños who had arrived, by-passing the road blocks, failing to observe social distancing, stockpiling essentials, behaving arrogantly. They were holding loud, night-long parties. One house was being used as a brothel. No evidence was ever posted to support these allegations. No police reports of illegal activity.

Now, ten weeks after the State of Alarm was decreed, the lockdown is being eased. People from the province can come to stay; soon, it will be any Andalusian. By the end of the month, any Spaniard. The stall-holders in the market are beginning to stock up with the expensive foodstuffs only outsiders can afford. The expensive restaurants are opening in anticipation of their arrival. But the fear remains— when they arrive with their flashy cars and designer clothes and refined tastes, will they bring the virus with them too?

Montreal

As humans, we have an incredible ability to shrug off the abstract when it doesn’t directly affect us or touch our daily lives in some tangible way. It is an ingrained survival instinct, perhaps. Our daily news feeds are replete with tragic stories: war in a distant country and famine in another; incurable illness; lives lost; and people denied basic rights. Prejudices, past and present. But even the best-intentioned among us only manage to pause our busy lives briefly to contemplate these realities. We spend a fleeting moment pondering tragedies, we dispatch a ‘how terrible’ or a ‘how sad for those people’, and then we move on.

We do not move on because we are unsympathetic or because we do not believe that it merits our time. It’s simply because, well, it hasn’t touched us quite close enough to home. It is not our country at war or our village ravaged by famine. It is not our family member who has the rare illness or our neighbour who has been unjustly arrested. In short, it’s something that has happened to unknown others, not to us, not to me. Compassion near-sightedness, in effect.

We could all benefit from a change in perspective. A slight readjustment to the lens through which we see the world. New lenses to correct our failure to see and feel for people far away or different from us—bringing that which is abstract and far-off, closer to home and clearer into view. What if it were my country, my village, my family member or my neighbour?

Which brings me to the source of these musings, which is two-fold. It is my hope that neither has touched you directly. Although, regrettably, I know that cannot be the case.

Firstly, the pandemic caused by COVID-19. We all understand the nature of this pandemic and have felt its impact. And yet. We all know the numbers, the data points that form the pandemic curve: 350,000 people (and counting) globally have succumbed to COVID-19. 350,000 people. But, unless you know someone who has been sick or someone who has died, these numbers and the curve they form are abstract. We still manage to be consumed by problems closer to home: having to wear face-masks in public, waiting in grocery store line-ups, working from home while juggling home schooling—problems that are by no means unimportant or easy to fix.

My wife’s grandmother is among the dead. An Italian immigrant who came to Canada well over sixty years ago seeking a better life for her family, Nonna Betty was 97 years young when she died of COVID-19 on May 1, 2020. She remained a force to be reckoned with until the end. She always said (in a strong Italian accent, despite all those years in Canada) that it was better to get old than to die young. She still saw 97 as ‘young’, and her spirit and determination remain a lesson for our entire family. So if you do not yet know anyone who has died of COVID-19, you do now.

Each one of those data points is—was—a real person. Each one was someone’s grandmother or grandfather, wife or husband, parent or child. A real person, part of the fabric of life, not a number.

Secondly, the tragic and senseless death of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Mr. Floyd’s death has triggered protests in the United States and around the world. It is a grim reminder of the extent to which intolerance and racism still exists.

Mr. Floyd died after a police officer kneeled on his neck for more than eight minutes, while he was handcuffed, despite cries of distress and pleas for air. This is distressing enough. The fact that George Floyd was black and the police officer was white, however, changes everything. Minorities in general, and people of colour in particular, do not enjoy the privileges that most white people in many parts of the world simply take for granted. The manner in which Mr. Floyd’s life was cut short demonstrates this. It is one in a litany of eerily similar deaths. It is easy to believe that some parts of the world, perhaps even those in which you live, are ahead of others with respect to the advancement of minority rights and the slow march towards equality that comes from it, but no part is immune from the insidious nature of racism, overt and implicit. It is a pandemic of a different sort, and no less tragic or deadly.

The death of Nonna Betty at the hands of COVID-19 serves for me as a deeply personal reminder of the real people behind the staggering numbers taken from us during the pandemic. It makes it real because it is no longer abstract. As horrific as the videos online are, I do not have a tangible, personal reminder of the racism that people of colour face. As a white man, I have not been subjected to the systemic racism endured by Mr. Floyd and countless before and around him. Racism and white privilege most certainly exist. But they remain abstract concepts for many—despite our best intentions to see them, recognise them and call them out.

I have ‘seen’ mortality in this time of pandemic. Now, I am conscious of the need to bring racism and injustice out of the abstract and closer to home. I need an altered perspective; a slight readjustment to the lens through which I see the world; new lenses to correct my own compassion near-sightedness—bringing the abstract into sharper focus. What if George Floyd were my brother, my father, my co-worker or my friend?

Newcastle

Before, I was never a big fan of having a routine. Other than work and exercise, I preferred to keep my free time as open as I could, avoiding early morning weekend commitments in favour of late-night spontaneity. It worked. I had fun. My early twenties might not have been as jam-packed with events as my time at university, but the lack of a set weekend routine meant that I could fill my time with friends, family, and days out without having the commitment of pulling myself out of bed at an ungodly hour such as 8am.

Now, I’ve found comfort in my lockdown routine. I work out on Monday, Wednesday and Friday evenings. I schedule lunchtime runs on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, plugging them into my phone calendar so I can’t avoid them as easily and can treat my local area to a red and sweaty face right on schedule. On Sunday I’m on my bike, before returning home for Sunday lunch with my parents at 4pm. Half an hour at night for reading, and I try to avoid any gaming after 9pm on weekdays. Curbing Netflix bingeing has been a challenge—two episodes per evening, to make sure I don’t exhaust their entire back catalogue. Extra time at home has meant I can help out more walking my two dogs; I couldn’t not make time for them. Saturday evening is reserved for the best of them all: the holy Zoom quiz. Meals are planned on Sunday, which is the perfect day to dream about food.

But this bubble I find myself in is far removed from the reality of many people’s lockdown routine. While my routine is an escape from worry, for others, routine is their worry. People like my parents, emergency services workers, who go to work each day to help those in need but lack the adequate equipment to keep themselves safe, and who return home each night worried whether tomorrow will be the day they wake up with symptoms. Or my grandparents, who only live up the road but have had their work postponed and income depleted, outdoor spaces like their allotment patch now a risk, plants withering, their new routine confined to four walls. And my friends, furloughed with no routine at all.

Or the ones without gardens, whose routine keeps them within the confines of their flats, shut in, fearful of taking rest in a park. The ones living with abusers, trapped. Families and single parents without the disposable income to keep their children entertained for weeks on end or subscribe to the latest streaming service. Our bus drivers, warehouse workers, corner-shop owners, supermarket staff and many more who do not have the luxury of working from home, whose routine puts them in contact with strangers—they can take all the precautions they like, but fate, and the actions of others, govern their routine of safety.

Routine can be a liberating way of creating an illusion of control if you have the means to do so. I’m lucky, living at home, with no dependants and a job that enables me to keep myself safe. For others, lockdown routine is a trap of monotony, of anxiety, of a tunnel without a light at the end.

After, I’ll enjoy drinks with friends in the Ouseburn. I will sleep in again on Saturdays and on lazy Sundays. Real quizzes will replace Zoom. I’ll find a balance between unbridled spontaneity and meticulous routine. As for running? Ask me later.

Singapore

The past weeks have been an exercise in adaptability—try minding a toddler intent upon climbing a high chair while you are speaking with a client—but they have also presented an opportunity to be grateful. I don’t go to work these days. I wake up in the morning and I am already at work. But that is not how it is for the many retailers, service providers and hawker centers in Singapore unable to work remotely. So each time I get frustrated, I think of the good folks who work at the Wheat outlet in Level B2 of the Marina One tower and wonder what they are up to, and whether they have had a paycheck come in any time over the past ten weeks. And now we are starting, slowly, to surface from COVID-19, trying to regain our footing. Our 60-day circuit breaker in Singapore came to a cautious end in early June (although most people who can work remotely are still doing just that). I can only speak for me, but I have emerged with a greater appreciation of the world we live in and how we treat it—and of the people who care for us and how we care for them. I am grateful.

Beijing

农历庚子年春节,突如其来的疫情改变了一切。没有万人空巷,没有辞旧迎新,人们像老鼠一样蜷缩在家中祈祷岁月静好山河无恙。随之而来的,是复工和开学的延期,以及远程办公的初体验。

远程办公看上去很美,但对于两个三岁孩子的妈妈而言,甘苦自知。被疫情囚禁的日子里,幼儿园关闭,阿姨被困家乡,彼时的远程办公更多地意味着需要同时分饰多角。虽然节省了通勤时间,但往往需要更长的时间连接VPN。记得最开始在家里办公时,VPN极其不稳定,加上电脑的某一个数字键失灵,只能一直等到不含有这个数字的Token出现才能连上VPN。每次成功联网后,一边喜极而泣分秒必争,一边随时准备迎接下一次网络断开。网速绝对不是唯一的考验。孩子们的心情会直接影响我的工作效率。面对电脑企图工作的我可能已被左右夹击,扯住头发,扼住咽喉,被逼问外面还有没有病毒,什么时候可以去游乐场。她们有时也会不约而同地放过我,安静和平地在角落里看书。彼此相安无事,弥足珍贵。

夜晚来临,月光倾泻在阳台上。结束一天的工作,看着酣睡的孩子们,轻声跟自己道声“早安”,属于自己的时间终于来临。面对来之不易的自由,竟然有些束手无策。困倦不堪,却不忍睡去。

The sudden onset of the pandemic changed every bit of the Spring Festival in this year’s lunar New Year in China. The streets were not filled with people, there was no celebration as of old. Like mice, people returned to their homes and stayed there, praying for peace, praying for no harm across the land, across the mountains, across the rivers. There followed the time of remote working and changes to schooling. How lovely that sounds, the thought of working at home, not having to go out to go to work. But I am the mother of two little children: I knew better. It would not be so easy. The kindergartens were closed and my children’s nanny, who had gone home for the Spring Festival, was unable to return. I had to work and I had to do all the other tasks required of me, on my own. The festival brought me some time but the protracted pain of connecting to VPN took away that time. It was a nightmare at the beginning, with the signal constantly going down: I was constantly having to restart, reboot, regroup. When all went well and I was online, I had to ‘seize the moment’ while standing ready to face the next crash. The Internet speed was the least of my problems. It was the children. They are twins, three years old. My effectiveness at work was in direct proportion to their mood on the day. There I’d be, at the computer, suddenly under attack, pummelled, hair pulled, hands round my throat, with demands as to whether the sickness had gone away and when could we go to the playground. Now? If not now, when? Sometimes—precious times—they released me, and they sat peacefully, contentedly in a corner, looking at their books; and all was well. In the evenings, the moonlight poured onto the balcony. I had done a day’s work, the children were sweetly sleeping, even as I said a quiet ‘good night’, and I finally had some time for me. Hard-won freedom. I didn’t know what to do with it, I was so tired, sleepy; but I didn’t want to sleep, couldn’t sleep.

Sydney

Sydney, New Year’s Eve 2019

The big Australian sky has a Bladerunner hue today. It has had for most of December—an apocalyptic orange: the colour of a world gone wrong. This is not part of the script. The script is: blue heavens, carefree summer Christmas, breathtaking fireworks for the New Year. Not this year. It’s not so easy to take breath this year. The eucalyptus tinge to the Australian air has an acrid edge to it—it gets between the teeth, grinds away. There is a foreboding that hangs in the air with the smoke. Australia is in the grip of a firestorm that could become an annual affair. The surfeit of carbon, further augmented by this summer’s blaze, has us in a chokehold. I check each day and the water in the dams inches downwards—Dubbo, five hours inland: it’s got two per cent in its reservoir. For once, climate change is not ‘caused by the rich, suffered by the poor’; for once, we can see how the planetary organism suffers—systemically—when its lungs are starved of oxygen. The city holds its breath. There is talk of calling off the fireworks, our iconic New Year Harbour display. It seems right to cancel. There’s a fire ban in the state, lives have been lost, houses destroyed: there’s little to celebrate. …As night draws in, a coastal wind picks up. It’s clearing the smoke. This wind is so strong that the talk has shifted from smoke inhalation to what happens if the fireworks are blown off course.

Sydney, 31 March 2020

They used to think malaria was contracted from bad air. That’s how it got its name. Maybe COVID-19 is the real malaria: the miasma that lurks in the air, that takes grip on the very airways it uses to propagate, and at the end grips those airways shut. My 95-year-old grandmother says this is more frightening than World War II. This time, we’ve got an enemy that hides on every surface, and with every breath is more present than one that exists on some far-off frontline. The country holds its breath. The whole world holds its breath. Try not to breathe in the virus; hope that this will pass; wait to see what the future holds. There are glimpses of hope: the idea that the strong would consent to so radically close the country down in order to protect the weakest and most vulnerable among us; the paradox of an isolation that, shared by so many the world over, makes us feel more bound together—globally—than we have felt before. Life will not be the same again. Office life will change, yes, but what else? This new-found sense of justice—will that endure? Might we be about to recognise, finally, that ‘the earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens’? Every breath I take, there is fear and there is hope.

Sydney, 6 June 2020

Is that the whiff of hope in the air? The payoff that almost makes sense of COVID? A recognition of our common humanity—and an impulse to not tolerate the suffering of the disempowered? The world changed after the sacrifices of World War II, so maybe it will be better again after the reset that was lockdown. It is hard otherwise to explain this movement sweeping the globe faster than the pandemic. Australia has its own long history of disregarding black lives, but the protests I am looking at today are in response to an unjust death in another part of our ‘one country’, this little globe. There are protests going on right now in backwaters of Australia that once seemed so far removed from Minneapolis. There are three hundred marching in Launceston. Do you know where Launceston is? It’s an insulated town in Tasmania, itself an island, off the island that is Australia. But Zoom has made us all citizens of the same neighbourhood, as we emerge blinking into light and breathing shared air, to stand up for a man whose choking, gasping words might just inspire us to make the world better than it is.

New York

One might think to seek comfort through literature when social distancing. There are many tales to choose from, and many involving how a plague might change humanity.

Station Eleven is set against the backdrop of a virulent flu pandemic that emerges from Georgia and kills 95 per cent of the population of North America. It was written by Emily St John Mandel, a Canadian author. The best thing about this novel is a troupe of actors and musicians—the Travelling Symphony—who, twenty years after the event, travel with their caravans among the remaining outposts of civilisation. The group circles the Great Lakes, performing for local communities in return for food and lodging. Their repertoire includes modern plays, but it is always Shakespeare the apocalypse survivors want, his words resonating with them.

Shakespeare’s life was played out against a backdrop of plague; he lived through quarantines and he experienced ‘social distancing’. Early Modern restrictions on gatherings repeatedly closed theatres. In the five years from 1606 (during which time Shakespeare wrote Macbeth and The Tempest and a number of other plays) the London theatres were, if the reports are correct, open for no more than nine months in total.

Macbeth is my favourite, I think.

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

It sometimes seems that the similarity of days spent in lockdown has an oppressiveness all of its own.

Attending a play is a fundamentally communal act. Reading is ultimately solitary. Living in a time of pandemic, when all normal societal functions, not just the theatre, have been affected, I realise that the thing I miss most is community. I took hundreds of small interactions with people for granted—these have given way now to stepping down from the pavement to the road to maintain a distance of two metres from someone approaching me.

It is also community that will be my abiding memory of this time. I flew from New York to London in early March, before the travel restrictions started, and I have been in London ever since, in a small terraced house. I feel I now know most of the street from clapping at our doorsteps every Thursday evening. I exchange cheery waves with others, not knowing their names but confident that they will be friends once this ends.

Close by is a pedestrianised crossroads, with a few shops and a restaurant. In a flat above one of the shops lives a couple, one of whom is an accomplished pianist. A tradition has emerged whereby, every Saturday morning, the pianist opens his window and plays. At first, his playing entertained only elderly neighbours and a few people in the immediate vicinity, who would stand outside, while social distancing, and listen to Chopin and Mozart, paying little heed to the disturbance from passing cars and oblivious walkers shouting into their mobiles.

A couple of weeks in, a local man in his thirties added a song or two, in a beautiful tenor voice. The pianist began to include popular favourites for everyone to sing along to. (You can get the lyrics to almost any song by googling the title on your phone.) It has rather got out of hand—thankfully coinciding with the easing of restrictions—and last Saturday there were more than a hundred people, all carefully distanced, some of whom brought tables and chairs and the odd glass of Prosecco. The restaurant made pastries and coffee and talked about when they hoped to reopen.

A police van happened to drive by. The crowd was singing ‘Let it be’, little knowing at the start that the chorus would become a polite request to the police to let them go on singing. They did.

Paris

Si le confinement a pu être perçu comme une contrainte ou une frustration, il a aussi pu être l’occasion de voir deux films, Les Misérables de Ladj Ly et Pirhanas de Claudio Giovannesi, sortis tous deux en 2019, apportant un éclairage assez opportun sur les notions d’enfermement ou d’isolation et nous invitant par là-même à relativiser l’importance des restrictions subies.

Les Misérables se déroule en banlieue parisienne, à Montfermeil, Seine-Saint-Denis, Quartier (ou cité) des Bosquets, l’un des plus pauvres de France, isolé de Paris pourtant proche, au même endroit précisément ou le chef d’œuvre de Victor Hugo du même nom se déroule en partie. Stéphane, jeune policier, rejoint un groupe de «Bacqueux» composé de Gwada et Chris, ce dernier dirigeant son unité de jour avec autorité et abusant de celle-ci régulièrement à l’encontre des habitants de la cité. La pression continuelle subie par ces policiers amènera l’un d’entre eux à commettre une bavure, laquelle sera filmée par un drone commandée par Buzz, un jeune de la cité, la quête de cette vidéo révélant la vraie nature de chacun des corps (police, frères musulmans, trafiquants, maire, jeunes) composant la cité.

Si l’entame du film peut paraître assez conventionnelle (personnage néophyte à qui les anciens expliquent la vie du quartier), Les Misérables touche assez rapidement sa cible et, à travers cette présentation sociologique sommaire de la cité, offre une idée de la vie qu’on y mène. Si les plus jeunes ont conservé leur insouciance (scène d’attaque de la voiture de police par des enfants armés de pistolets à eau, à la manière des indiens) et les frères musulmans tentent de faire subsister un semblant de morale, c’est bien la violence qui est omniprésente, tant dans le langage des protagonistes que dans les rapports de force qui s’y expriment. La réponse apportée par l’Etat, représentée pour l’essentiel par le policier Chris, se résume à des abus de pouvoirs constants et à l’expression d’une violence tout autant illégitime qu’elle s’exprime par celui-là même qui est censé la réprimer. La situation étant devenue hors de contrôle, Stéphane apostrophe alors Chris en le corrigeant sur le fait qu’il voudrait inspirer le respect, alors qu’il n’arrive qu’à insuffler la crainte: quintessence de l’échec pour celui qui cherche à utiliser son pouvoir à bon escient (mais Chris le souhaite-t-il vraiment?).

Les Misérables va s’élever encore un peu au-dessus des poncifs du genre: là où le film de gangsters (reflétant en cela une idée reçue de la société plus généralement) aime à jouer sur le fantasme d’un pouvoir ou d’une autorité occulte dominant les zones de non-droit, le film va apporter une réponse pleine d’humanité et de bon sens: aucun corps ne prime, tous se tiennent et rien ne peut contenir l’explosion de violence lorsqu’elle exprime le besoin de justice des opprimés. Nous pensons alors évidemment à Do The Right Thing, étalon maître du cinéma moderne en la matière.

La cité, vase clos isolé du reste du monde, restera finalement tel quel tant que la violence—entretenue par l’Etat et ses institutions—restera omnipotente, condamnant ainsi ses habitants au ghetto et à l’ostracisme. Le visage et les rires des petits «indiens» attaquant la diligence n’en sont que plus bouleversants.

Tiré du roman éponyme de Roberto Saviano (2016), Piranhas (La paranza dei bambini) se déroule quant à lui dans le quartier de la Sanità à Naples. Nicola, Tyson et leur bande composés de jeunes adolescents vivent de petits larcins. La première scène édifiante nous les montre subtilisant un arbre de Noël géant tout en se confrontant à une autre bande de voyous, annonçant l’amoralité et la cohésion qui guidera le groupe tout au long du film. L’activité illicite de la bande restant toutefois limitée, leurs désirs matériels (boîtes de nuit, vêtements…) demeurent largement inaccessibles, de même que la jeune Letizia, adolescente au visage d’icône immaculée rencontrée furtivement par Nicola un soir. Dans le même temps, ce dernier ne peut que constater impuissant au racket de sa jeune mère, exploitante d’une modeste blanchisserie, par le groupuscule camorriste local. On imagine alors aisément que lorsque la possibilité se présente de dealer pour ledit groupuscule, l’occasion est trop belle pour Nicola et sa bande. Rapidement intégrés, ils iront jusqu’à s’arroger la direction des affaires criminelles du quartier, aidés par un coup de filet de la police et approvisionnés en armes de guerre par un parrain rival, satisfaisant ainsi provisoirement tous leurs désirs, y compris pour Nicola la conquête de Letizia. La violence prendra finalement le contrôle de leurs destinées, sans que le film nous assène pour autant une conclusion définitive.

Le réalisateur, Claudio Giovannesi, nous dit que, pour ces jeunes napolitains livrés à la criminalité et à la violence, la seule issue est une mort violente ou la prison. On veut bien le croire et on s’interroge: en ont-ils conscience? Peut-être la question pertinente est-elle celle de l’alternative, Sanità n’offrant semble-t-il pas beaucoup d’autres options à Nicola et sa bande pour échapper à l’humiliation et à la frustration, quand bien même l’issue serait connue d’avance. En cela, Piranhas se situe dans la tradition des grandes peintures littéraires de Naples. On pense bien sûr à Léopardi et Malaparte et, dans un dernier geste de mise en scène d’une rare intelligence, Claudio Giovannesi nous en livre sa version moderne, sans conclusion ni morale, la violence engendrant inexorablement la violence et frappant les plus innocents de manière tragique et foudroyante.

Ces deux œuvres nous offrent chacune leur vision naturaliste de l’enfermement géographique, sociologique, culturel et moral. Le réalisme sociologique de Ladj Ly laisse la place à un récit plus romantique et lyrique chez Claudio Giovannesi (sublime musique de ce dernier et d’Andrea Moschaniese), mais en substance l’impression est la même, chaque société créé ou laisse subsister ces ghettos pour y maintenir ses damnés. L’Europe y recourt depuis le moyen-âge mais, à la vue des enfants sacrifiés, ce constat froid devient soudainement bouleversant et intolérable. Revenant au propos introductif, la notion de «confinement» prend dès lors une toute autre ampleur.

Tentant de remédier à cette isolement culturel, Ladj Ly a contribué à l’ouverture en 2018 d’une école de cinéma à Clichy-sous-Bois - Montfermeil.

Lockdown afforded me an opportunity to see two films: Ladj Ly’s Les Miserables and Claudio Giovannesi’s Pirhanas. Both were released in 2019 and both cast a timely light on our understanding of confinement and isolation.

Les Miserables is set in Montfermeil, Seine-Saint-Denis, in the Bosquets quarter. Close to Paris yet cut off from it, this is one of the poorest cites in France. Victor Hugo’s masterpiece of the same name is situated here.

Stephane, a young policewoman, joins a group of Bacqueux—street slang for the Brigade Anti-Criminalite, or Vice Squad. The unit is under the command of Chris, who routinely abuses his authority in his dealings with the locals. Under the relentless pressure someone screws up and the act is captured on film by a drone controlled by a local youth. The ensuing search for the incriminating video shows all the protagonists—the police, the youths, the Muslim Brothers, the drug-traffickers, the Mayor—for who they really are.

The early scenes in Les Miserables are pretty standard fare (old hands show new kid on the block what life is like) but then the camera shifts its focus and starts to paint a picture of the lives lived in the cite. The children are ‘carefree’—as we see in the scene where a police car is ‘attacked’ by children armed with water pistols, Wild West style. The Muslim Brothers are trying to preserve a sense of morality. But violence permeates this film, in the power struggles and the language of the protagonists. The response of the State, embodied in Chris, culminates in a level of violence all the more illegitimate for having as its perpetrator the very person supposed to suppress it. It all spirals out of control. You are instilling fear, Stephane tells Chris, not commanding respect. Is that what you want?

Les Miserables rises above most of the clichés of the genre. The typical gangster movie likes to play on the idea of a powerful force able to impose its presence on no-go areas. In Les Miserables no one dominates the action, they stand together, and nothing can prevent the explosion of violence, laden with the need for justice for the oppressed, when it comes. This is a film that brings to mind Spike Lee’s 1989 masterpiece, Do The Right Thing.

The cite is a sealed vessel, its inhabitants condemned to a life of ostracism, a life spent in the ghetto. And so it will remain for as long as there is violence, fomented by the State and its institutions. This makes the grinning faces of the children attacking the stagecoach all the more disturbing.

Piranhas (La Paranza dei Bambini) is set in Naples in Italy, in the district of Sanita, where a tight-knit band of adolescents live off the proceeds of petty crime. They are small-time players. Their ambitions (to go to night clubs, to own fancy clothes) remain beyond their reach. As does Letizia, the girl with the iconic face. The male leader of the gang, Nicola, watches helplessly as his young mother, who runs a laundry, becomes prey to the local Mafia, the Camorra. So, when the gang are offered the chance to become ‘dealers’, it’s too good an opportunity for them to pass up. By the end they have assumed control of the neighbourhood and can finally satisfy their every desire—including, for Nicola, the conquest of Letizia. Violence takes over, inevitably.

For these young Neapolitans, mired in a life of crime, amorality and violence, the only outcome is prison or a violent death. That’s what the director, Claudio Giovannesi, is telling us, and it’s hard to argue against that. One wonders: are these young people conscious of this fate awaiting them? And even if they are, what alternative is there for Nicola and his band of brothers, given all that Sanita cannot offer them?

Piranhas is rooted in the tradition of Leopardi, Malaparte, other great Neapolitan works of literature. In a cinematic work of exceptional intelligence, Giovannesi gives us a contemporary interpretation of this tradition. The film has no conclusion. There is no moral to the tale—other than that violence begets violence and afflicts the innocent in a manner as tragic as it is horrific.

Both films offer their own take on confinement but in essence they are saying the same thing: every society creates—or perpetuates—ghettoes in which to lock in its malcontents. We have been doing this in Europe since mediaeval times. We know this. Yet, when we see children sacrificed, this fact becomes suddenly disturbing, intolerable. The whole notion of ‘confinement’ and ‘the nature of confinement’ takes on a different dimension.

London

Let’s get this out from the very start: my wife (Ruth) is my hero. Aside from being a wife and a mother, her day job is the Lead Occupational Therapist for the respiratory medicine team at a large west London hospital. During lockdown, she moved to ICU/ITU dealing with COVID-19 patients. I’m not going to go into the detail of her experience working on those wards but it was—horrific.

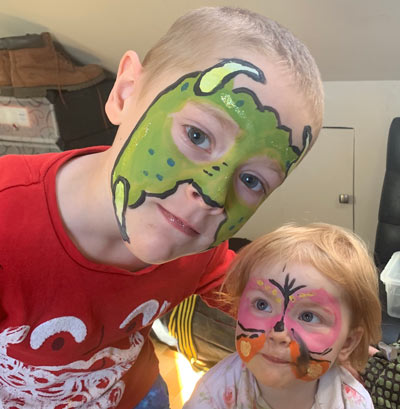

Unsurprisingly, Ruth contracted Covid19 early on, and the house went into isolation. I drove her to the Drive-thru testing station and we had the virus confirmed. Fortunately, Ruth had the fairly mild version; she spent most of her time at home desperate to get back to the hospital to help. Those two weeks were largely taken up with our attempts to keep our children entertained. It soon became clear that every wall in our home was going to be personalised with colouring pens.

From memory, it was the same day we visited the testing station that I started to feel unwell. Within forty-eight hours it was clear I had the virus, and my health deteriorated rapidly. I lost my sense of smell and taste; I was constantly coughing; breathing was becoming an issue; and I was sleeping no more than an hour a night, which drained my strength. Without sounding dramatic, my heart and lungs ached intensely from the inside out. Mentally I went to a dark place, going through all the possible outcomes considering how unwell I felt, coupled with my diabetes. Fortunately, after two weeks my GP gave me antibiotics and I had a cpap machine to wear at night to help with sleep and breathing. It’s now been five weeks and I finally feel like I have got my strength back.

Today will be my sixtieth day at home. I’m lucky to have an office at home so that I can easily separate work and family life. Not that I don’t occasionally get a random visit while I’m in a Skype meeting.

As a family, we have been lucky with support from schools, nurseries and shops, because my wife is a Key Worker. The amount of food donations for Key Workers that my wife’s hospital receives on a daily basis is truly humbling. My children’s local school and nursery has stayed open, making sure they’ve had the consistency they need, and this has relieved a lot of the pressure on us. It has been a difficult time seeing Ruth come home physically and mentally tired from work while I was unwell. I feel grateful for having such a strong community around my family.

The recovery is very slow and I still get waves of tiredness hit me without warning. Looking at the positives I've been lucky to recover without any permanent damage.

Stay safe and well!

Neil

Los Angeles

In the high Sierra Mountains, the wildflowers are starting to emerge, resilient to winter’s cold and darkness. And resiliency is on my mind during this time of pandemic, economic dislocation and civil unrest unsettling the minds and the livelihoods of people in the Los Angeles basin.

David Winn was a US soldier in the Vietnam War. I met him when I was a university student. He was captured in North Vietnam in August 1968 and not released until March 1973. As a POW, he and fellow prisoners faced solitary confinement, deprivation and physical abuse. During their long time in captivity, the prisoners developed complex informal systems—a society built through secret communications, sometimes with the outside world. Prisoners knew that they were not alone. They helped each other by boosting morale and providing material aid where they could. And prisoners kept their sense of humor. While they accepted the reality of their circumstance, they did not give in to get along but pushed and pressed their captors. From these experiences the military code of conduct for POWs was changed: captured soldiers no longer have to choose between full compliance and death. Resiliency can bring lasting positive change.

May we, too, individually endure through the present misfortune. May we be resilient in the face of COVID-19, hold fast and recover our balance quickly, able to face the changes to our economic and business environment that will follow.

Sydney

The poet Boccaccio wrote in The Decameron of the onset of the bubonic plague that devastated medieval Europe in the fourteenth century—nearly seven centuries before our own modern-day plague swept through our globally connected world at warp speed:

“In the year then of our Lord 1348, there happened at Florence, the finest city in all Italy, a most terrible plague; which, whether owing to the influence of the planets, or that it was sent from God as a just punishment for our sins, had broken out some years before in the Levant, and after passing from place to place, and making incredible havoc all the way, had now reached the west.”

The Black Death was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis (not by a coronavirus, like COVID-19). Its transmission to humans was zoonotic: the original vector is thought to have been rats; these were bitten by fleas, which in turn passed the disease onto humans. Most epidemics throughout history have been caused by zoonotic diseases that have ‘jumped’ from animals to humans. This has occurred often through the domestication of animals: we see it in pigs (smallpox, measles), chickens (chicken pox, bird flu) and cattle (tuberculosis).

In the fourteenth century, Genoese merchants plyed the land and sea trade routes that had developed between Asia and Europe, and amongst their cargoes they transported infected rats and fleas. The Black Death struck Italy in 1347, when merchant ships disgorged infected seafarers at the port of Messina. Within just two years, the plague had spread across all the ports of Europe. Venice was the first city to close its port to ships; any permitted to enter were forced to quarantine for forty days—the word quarantine derives from the Italian quarantena (forty days). By 1350, the whole of Europe had been infected.

The Black Death overwhelmed medieval populations. People died within days, once infected. Fields lay fallow. Animals were left unattended. Famine ensued. The populace were unable to look after the sick and dying and could not bury their dead. Anyone infected was made to ‘self-isolate’ in their home and had a red cross—the mark of the plague—painted on the door.

Historians estimate that the Black Death killed up to one half of Europe’s population. The magnitude of this number of deaths engulfed communities in a sense of apathy and hopelessness, and fearful populations neglected responsibilities to family and to trade and agricultural labour. Neither the nobility nor the Church could ameliorate the effects of the plague and this eventually led to a breakdown of their authority.

The changes wrought by the Black Death were profound: across Europe, there was massive social, economic and political disruption. But then, once the burden of impending death had lifted, the human population adapted. Society staged a spectacular recovery. The aftermath of the plague saw over time the growth of a more socially mobile merchant class, the end of feudalism, the rising up of the Reformation and the emergence of the Renaissance, the flowering of European art and literature. The foundations of modern Europe were forged in the Black Death.

Humans are the most adaptive species on Earth. Our modern-day plague looks set to be the precursor of a deep global economic recession, but—in time—its most pernicious impacts will recede and, if history is any guide, our world will be changed, fundamentally.

New York

We now live in a place we never thought we would. Always a big city child, I am suddenly and surreally surrounded by trees and grass and wildlife. There are the small pleasures of being around during the day to hear my son’s laughter fill the house or walking out to our new vegetable patch to see what might be eaten for dinner or stealing a few minutes to walk with my husband. The days tend to blend together now, without much structure or form; but I will cherish this stolen and exquisite time for the rest of my life.

Edited by Nicola Liu. Translation of 'Community' by Roc Gui. Translation of 'The mother' by Nicola Liu and Rosalie Luo. Translation of 'Cinema' by Flavio Centofanti with Nicola Liu. First published in RE: issue 17 (2020).

© Norton Rose Fulbright US LLP 2025