Features

Essays, stories, prose poems, surveys and critiques

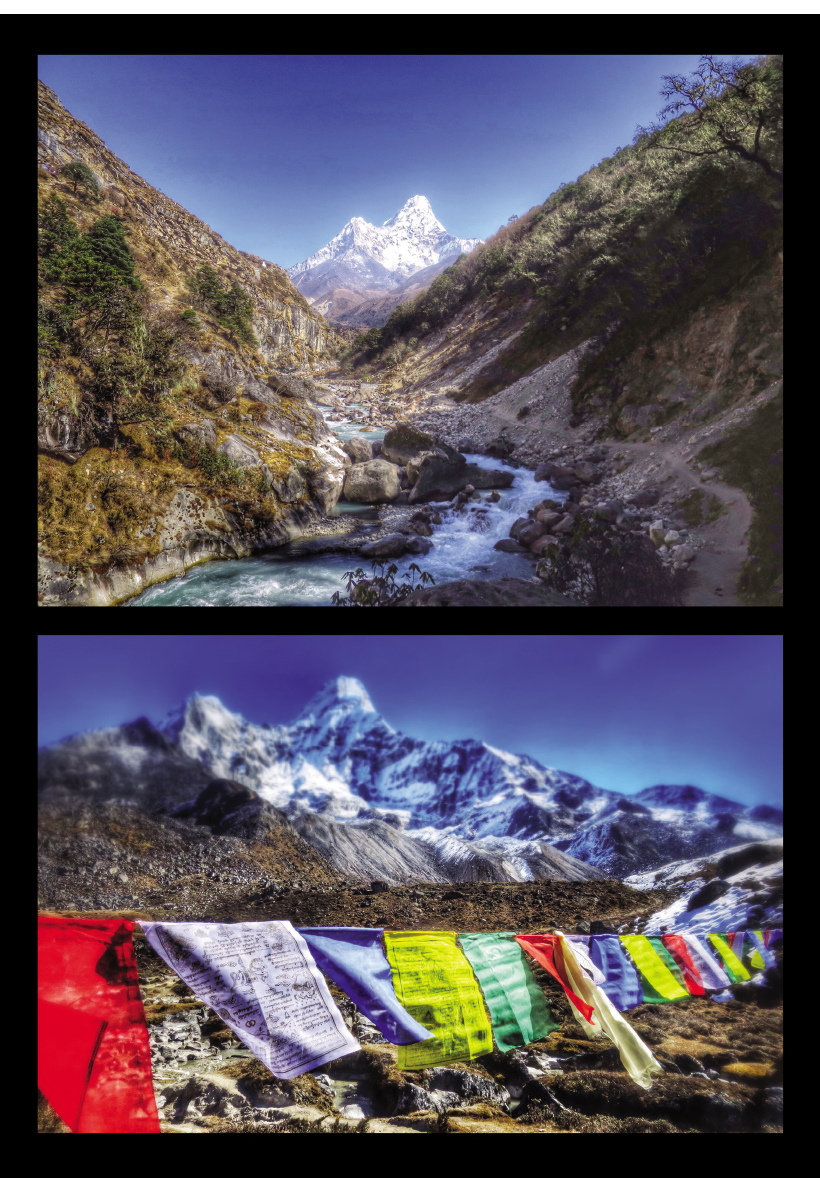

A M A D A B L A M

I did not see the rescue helicopter until it was right overhead. It was late afternoon and the winds had grown stronger, becoming a constant roar in my ears. I stopped for a moment, forced my ice axe into the snow, and squinted up into the bright Himalayan sunlight. As I worked to catch my breath, I could just make out the figure of a man dangling below the helicopter, attached to the rescue line. There was no doubt about it: he was dead.

This was not the first death amongst the climbers at our base camp. In fact, it was the fifth since I had arrived at Ama Dablam more than six weeks earlier. Ropes had failed, ice walls had collapsed, altitude sickness had taken its toll. The mountain had been particularly deadly this season.

More than sixty years ago, Sir Edmund Hillary spent an entire season at the foot of this Himalayan mountain, scouting, searching for a route to the summit. England was in need of another great mountaineering triumph to match Hillary’s conquest of Everest in the spring of 1953. Hillary and his team scoured the lower slopes of Ama Dablam in search of a path to the top, but they eventually had to declare defeat. Sir Edmund wrote back to London, declaring the mountain ‘beautiful but unclimbable’. Ama Dablam was already known locally as ‘the mother’s necklace’; now it became famous as ‘Hillary’s unclimbable peak’.

But few peaks are truly unclimbable, and in 1961 the riddle of Ama Dablam was solved by a team of four climbers: mountaineer and doctor Michael Ward (from England); Barry Bishop (from Cincinatti in the US), who went on to become an acclaimed photographer with National Geographic and a scholar; and writer Mike Gill and builder Wally Romanes (both from New Zealand). Their ascent of Ama Dablam—the first winter ascent in the Himalayas—was not repeated for twenty years.

This exquisite mountain has grown in popularity, particularly with ‘experienced amateur’ mountaineers. At 22,349 feet, supplemental oxygen is not necessary, and the approach is less dangerous than for most of the Himalayan giants.

I first spotted Ama Dablam from the distance in 1986. I had just graduated from law school in Nova Scotia and was spending the summer in India, working in a little school in Darjeeling run by Jesuits. At that time, Darjeeling was deemed a ‘control zone’ by the Indian government and foreigners were required to leave the area every fifteen days and then apply to re-enter. The closest border was Nepal, and I spent my mandatory exit periods wandering the streets of Kathmandu and trekking through the countryside. I was young and I fell in love with Nepal. Kathmandu was all noise, excitement and colour: until, that is, you went into one of its many temples, and encountered a serenity and tranquility matched only by the sight of Nepal’s Himalayan giants filling their space in the landscape. As I trekked through the Himalayan foothills, I caught my first glimpse of Ama Dablam, far off in the distance. I made a mental note to return.

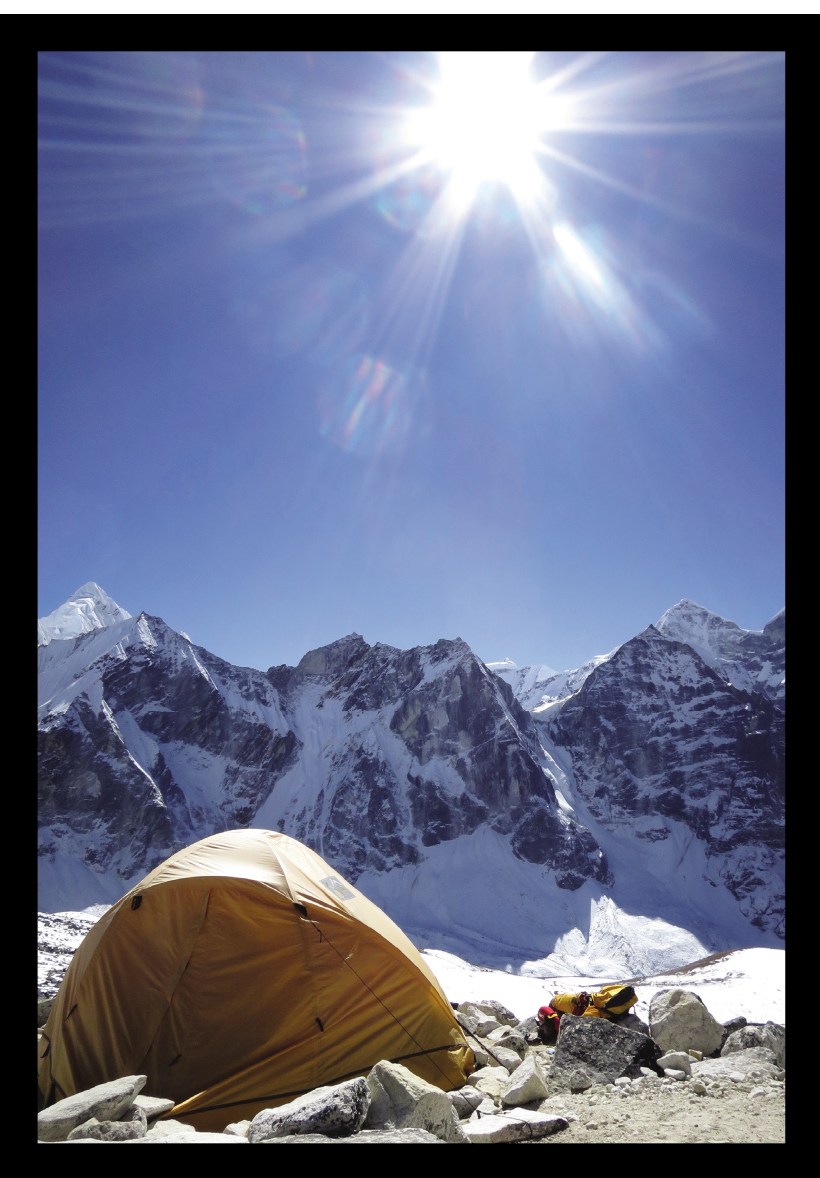

Nearly thirty years passed. I’d like to say I had grown fat and idle as a mountaineer and a dreamer of dreams but that’s not true. I had persisted: I had become an experienced amateur. And now I had returned to the mountain that had captured my imagination all those years ago. I was here, on the Himalayan range, climbing Ama Dablam, inching towards Camp III, more than 20,000 feet above sea level.

The idea of scaling this mountain seemed so much more romantic when I was 25. Back then, wandering from village to village, sleeping in little teahouses or on the floor of a local monastery, I had all the confidence of youth. Those days seemed a long way off.

The wind was cold and growing colder. My face was blistered from the sun. My feet were blistered from my boots. I was having a difficult time feeling my fingers. I was tired and sore and lightheaded. I had been six weeks without a shower. Six weeks sleeping on the frozen ground. Six weeks of eating a diet of Ramen noodles, rice, lentils and yak meat.

It was time to climb higher. I waited until the rescue helicopter and its ill-fated cargo disappeared down into the valley heading towards base camp. I stomped my feet to try and warm my toes, put my head down, and trudged upwards.

I had planned this climb of Ama Dablam for more than two years. Around the office people would laugh when I told them that one of my greatest challenges was finding life insurance. Trips into Yemen and Afghanistan with work had made me an underwriter’s worst nightmare. My wife is a practical woman and a mother of four. We agreed that I wouldn’t attempt Ama Dablam without back-up. She’s also an understanding woman, and when things changed and I was finally able to qualify for that last bit of insurance, my wife could see that it was time. I was getting older. If I wanted to chase down a dream, I shouldn’t put it off any longer.

I started to train in earnest, hired a climbing Sherpa and began rearranging my work commitments. As the training intensified so did the injuries; my old joints kept letting me down, so I always had something to grumble about. But, gradually, my fitness improved. Files were delegated, meetings were rescheduled, travel arrangements were put in place. It was now—or never.

After all that preparation, there was too much at stake to quit now. I stared at the rope that connected me to my Sherpa, and jabbed my ice axe into the mountain. I climbed higher.

But I couldn’t shake the image of that dead climber from my head. He was probably younger than I was, stronger than I was and better trained than I was. He probably had a family like I did. And now he was gone, dangling in the wind at the bottom of the rescue line as the helicopter carried him down. I thought about the others who had died on that mountain earlier that month. A strong American climber, an experienced German climber, a young Nepalese guide. I noticed that my pace up the mountain had slowed again.

I took one last look toward the summit and caught a glimpse of it just as the clouds closed in. I thought back to when I first saw the mountain nearly thirty years earlier. I was still at least six hours from the top and the wall of ice and rock known as the dablam (the necklace) loomed overhead. At night, in our little tents, we would hear great pieces of ice and rock thunder down the mountainside as the ice wall crumbled. Teams were now trying to figure out whether there was a safer route to the summit. This was the most dangerous part of the mountain. As far as we could determine, no one had reached the top in more than a week. I wondered if it really made a lot of sense for the first climber up the new route to be a middle-aged lawyer from the Canadian prairies.

I realized that I had already made my decision. It was time to shift my attention away from my dream and start to enjoy the experience. I knew it was not my turn to reach the summit. ‘Lakba!’ I shouted to my Sherpa, ‘It’s time to turn around and descend. Let’s go and find ourselves another mountain.’

Tom Valentine is a partner in the Calgary office of Norton Rose Fulbright

© Norton Rose Fulbright US LLP 2025