Introduction

Chinese outbound investment was on the decline before COVID-19 as Chinese regulators and Chinese lenders were forcing sponsors to focus much more on the quality of their projects. Since COVID-19, Chinese outbound investment has fallen off even further as China has refocused on investment in the domestic economy. Over the longer term, Chinese outbound investment will continue to be important, but in the short term, Chinese bank and ECA financings have become more difficult.

However, financings under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which is the flagship policy of the Xi government, will continue to be prevalent, although China is reacting to international responses to its policy and concerns that it was leading to the financing of white elephant projects. Norton Rose Fulbright is working on a three-year project with the Chinese government and the UK government on a project to improve the quality of BRI projects and to increase non-Chinese participation in BRI projects.

While Chinese investment in outbound mining deals has slowed, our dedicated China mining team continues to be busy acting for multinationals on China related matters and for Chinese counterparts on international deals.

This guide is intended to provide a framework within which to assess options for non Chinese clients. We believe it is the only guide of its kind focused on accessing Chinese capital for mining, power and associated resource infrastructure.

For those that feel they would benefit from further information we are happy to offer discrete training on all matters related to mining and accessing Chinese finance.

China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation (SINOSURE) – an introduction

SINOSURE is the official export credit agency (ECA) of the PRC. It was established in 2001 and took over roles previously filled by People’s Insurance Company of China and The Export Import Bank of China (C-EXIM). C-EXIM is not an official ECA, but similar to China Development Bank (CDB) is regarded as a ‘policy bank’ providing support (in the form of direct funding) to the economic/political policies of the PRC. SINOSURE’s key role is to provide commercial and political risk insurance cover to support Chinese companies.

It was not until 2003 that SINOSURE began writing policies covering classic ECA export risks, commercial credit risk and political risk, and Norton Rose Fulbright worked on one of the first SINOSURE-backed foreign financed projects in 2005. Like many export credit agencies, the bulk of SINOSURE’s business is in short-term support for Chinese exports. However its medium- and long-term underwriting has grown substantially in recent years – all very much in line with the Chinese government’s stimulus package for the economy.

In addition, in some instances, SINOSURE will also provide a guarantee of the offtake on certain projects.

SINOSURE has representative offices and branches across China and it is to the local office that the Chinese exporter will usually address its initial request for cover. A foreign project company seeking SINOSURE support for its project due to, for example, the involvement of a Chinese EPC contractor, will need to access SINOSURE through the relevant Chinese EPC Contractor – the foreign project company will not itself have direct access. This application process is typical of access to other ECA cover.

Requests for medium- and long-term SINOSURE cover are processed through the head office in Beijing and are subject to approval by the Ministry of Finance (MOF) for cover in excess of US$30 million and by the State Council for cover in excess of US$300 million, although these thresholds vary from time to time. Discussions with SINOSURE are usually begun by the Chinese exporter/EPC Contractor and then taken up by the bank arranging the buyer credit facility. There is usually limited contact with the buyer/borrower. Although more recently SINOSURE has tended to take a more active role in projects and SINOSURE will often participate in the meetings.

China is not a participant in the OECD gentlemen’s agreement on official support for export credits (the Consensus) but SINOSURE is nonetheless represented at the Berne Union and complies with the Consensus. SINOSURE provides up to 95 percent cover for political risks and has traditionally limited commercial risk cover to 50 percent, however in the current market there is now some flexibility in the level of cover for commercial risks and we have recently closed transactions with up to 95 percent commercial cover. The percentage of cover is run against the amount of the contract value which SINOSURE is able to support i.e. up to 85 percent of the total contract value, in common with other ECAs. SINOSURE cover is available for both Chinese and foreign banks who meet certain criteria (including a track record in export credits), although the foreign bank must have a branch in PRC.

As with all export cover, SINOSURE cover is only available in support of exports of the host country i.e. Chinese goods and services. This can be a flexible concept but the Chinese content should be at least 60 percent of the value of the export contract/project (although this threshold can vary from time to time and from project to project – until recently 70 percent was a more typical requirement).

The greater the Chinese connection to the project (in terms of economic interest for the PRC), the better the chance of obtaining cover and MOF/State Council approval. The China content requirement is somewhat opaque, but looks to the actual level of goods/services originated in the PRC or otherwise eligible for SINOSURE cover as determined by SINOSURE i.e. if the EPC Contractor is Chinese but subcontracts the construction to a non Chinese entity and/or sources relevant equipment and supplies from outside China, this may breach the China content requirement. Ultimately, sign off must be sought from SINOSURE up front, with the risk then passed to the Chinese bank and EPC Contractor going forward, (i.e. no event of default under the loan agreement for breach of China content, and an obligation on the EPC Contractor in the EPC Contract to ensure compliance with China content).

It is preferable for the purposes of obtaining SINOSURE cover that the export contract/ project should generate a supply of strategically interesting products or natural resources for China. However, we should note that the existence of a Chinese offtaker would not typically by itself satisfy the conditions for SINOSURE cover of debt into a project, irrespective of the value of that offtake contract – the cover is really in place to assist export of goods/services from China. However, assuming the requisite level of goods/services were supplied into a project, such an offtake would no doubt assist the likelihood that SINOSURE will be interested in providing cover in relation to such a project. Further, SINOSURE may be more willing to provide cover in relation to a project if there is an element of Chinese equity investment involved, in view of the stated policy of the PRC to promote and ensure acquisitions of interests in foreign assets, particularly strategic resource assets. It is important to appreciate the global strategic interests of the PRC and the relative position of any EPC Contractor and any export contract/project in the hierarchy of those interests.

As is the case for other ECA cover, a foreign sponsor, can only access SINOSURE through a Chinese EPC Contractor. Discussions with SINOSURE are usually begun by the EPC Contractor and then taken up by the bank arranging the cover. There is usually little or no contact with the borrower. There is also limited scope to negotiate the policy, but it is possible to make minor adjustments to some terms.

Although obtaining an initial response on underwriting from SINOSURE can be relatively quick – SINOSURE will generally sign a letter of intent within six weeks of SINOSURE receiving a complete file – the full process changes with Chinese policy on outbound, but the policy generally is issued within three to six months, depending upon the backlog of projects.

As a state policy institution SINOSURE is subject to directions given to it by MOF. New directions apply to cover from time to time, which SINOSURE has conditionally approved but which have not become the subject of binding policies, and can also apply retrospectively. From late 2008, SINOSURE began to require that all buyer credits be supported by a guarantee – preferably a state guarantee and for private sector buyers a parent company guarantee.

In current market conditions accessing either SINOSURE cover or Chinese bank funding is a possibility that few can ignore. SINOSURE has significantly expanded its capacity to underwrite transactions and has upgraded its country risk analysis and its country limits. Moreover it has experienced a huge surge in demand for its services and it struggles to keep pace.

Accessing Chinese bank/ECA facilities

We have set out below a generic set of questions and answers, which address some of the key issues that sponsors may focus on in seeking to understand their ability to access Chinese bank/ECA support for a mining project. This article provides only a summary overview of these points and further issues/detail may need to be investigated/discussed in relation to any specific transaction.

Although in this article we refer to the Export Import Bank of China (C-EXIM) and China Development Bank (CDB) as an ECA, we should clarify that C-EXIM and CDB are not strictly ECAs but state owned ‘policy’ banks through which official support are provided on terms that closely follow the OECD guidelines on export credits; SINOSURE is the only official Chinese ECA.

1. What level of Chinese bank/ECA facilities are offered? Is there any limit? Can a commercial loan amount be larger than the portion covered by an ECA guarantee/insurance cover?

There is no absolute fixed limit to the facility amount when accessing funds from Chinese institutions – we have advised on loans from hundreds of millions up to tens of billions from Chinese institutions.

Chinese commercial banks are willing to provide both covered [and uncovered facilities], although typically Chinese funding of commercial loans (particularly from a single lender) on a single project will be either ECA covered in full or fully uncovered, rather than partially covered and partially uncovered.

However, there are certain limitations on the amount of cover which can be obtained from Chinese ECAs:

- In common with all other ECAs, Chinese ECA cover is limited to an amount equal to 85 percent of the relevant export contract value, and the 15 percent contribution/down payment from the project company to the EPC Contractor is typically required as a condition precedent to loan disbursement/ECA guarantee provision. This 85 percent threshold is set by the OECD guidelines on export credits, although currently there are many temporary rules in place that have allowed ECAs to cover higher percentages and broader categories of eligible goods.

- For single asset project finance SINOSURE has typically only provided up to 50 percent commercial risk cover and up to 95 percent political risk cover however, when a parent company guarantee is provided (as is now typically required), particularly if of substantial credit value, it can provide up to 95 percent commercial and political risk cover. As more and more ECAs take measures to increase the percentage of cover that they can offer, we would expect SINOSURE to follow suit and become a much more influential source of cover in this respect – this is certainly the mandate from the Chinese state as it seeks to develop its strategic macro economic interests.

- For deals over a certain size (and the thresholds are both increased from time-to-time as the state widens SINOSURE’s mandate, and are also to varying degrees relaxed depending on the strategic importance of the project to be financed), SINOSURE requires separate approval from the Ministry of Finance (MOF) and/or the State Council. These approvals can take a long time to be issued, however the SINOSURE underwriting department is capable of giving a qualified response (subject to such approvals) within three days of receiving a complete submission.

2. What might one expect as the debt/equity ratio?

80:20 is the typical top end of the debt: equity ratio, but some can be 70:30.

3. In what currency will the loan be denominated? What is the base cost of funds?

Loans from Chinese institutions may be denominated in any currency. The vast majority of cross border lending is in US$, based on a LIBOR base rate, however we have seen examples of Euro lending and expect to see more non US$ financings as the Chinese institutions adapt to meet sponsor requirements. Increasingly we are also seeing RMB lending. For other currencies Chinese banks can be expensive.

C-EXIM direct funding to suppliers is typically tied to the currency of the relevant export contract (typically US$, though again there is flexibility).

4. In what currency will the supplier/EPC Contractor be paid?

As noted above, in cross-border transactions, the supplier/EPC Contractor will typically be paid in the currency of the relevant supply/EPC Contract (whether through commercial bank or C-EXIM funding). Renminbi may be used unless the relevant supplier/ EPC Contractor is a foreign entity requiring payment in foreign currency.

5. Is the supplier/EPC Contractor paid directly by the Chinese bank?

Typically Chinese bank funding will be made available direct to the supplier/ EPC Contractor (following a drawdown request by the borrower), unless it is to be used to refund the borrower for payments already paid to the EPC Contractors/suppliers. Drawings require a supplier’s/ EPC Contractor’s disbursement request to support a borrower’s drawdown request.

6. Must all deals have a Chinese offtaker? If there is no Chinese offtaker what security is required? Do Chinese banks look for charges over payment accounts? In what instances might a parent company guarantee be required?

It is not strictly necessary to have a Chinese offtaker, although the state banks and ECAs require some form of Chinese component to the deal, whether this be a Chinese offtaker, equipment supplier or EPC Contractor – see China content section below.

The security requirements of Chinese banks can be much softer than typical Western bank financing, however this tends to be the case where there is a strategic interest for China in the project and a public sector interest in the host country. However, where there are no such strategic interests and the Chinese lending arrangements are purely commercial funding terms then the Chinese bank/ECA will request full project finance style security plus a parent company guarantee.

7. Is it traditional for Chinese banks to look for hedging of commodities?

Unlike typical international financing of mining projects, Chinese banks do not usually require any commodity hedging.

8. Is there a standard form of facility documentation? Is it LMA based?

There is no official standard form documentation which Chinese banks work to, however each bank tends to have its own standard form which is an LMA-based form. The documentation is becoming ever more ‘Westernized’/LMA-based, particularly on international syndicated transactions as China becomes more involved in international cross border transactions. Norton Rose Fulbright prepared the original precedent for CDB using APLMA precedent wording.

SINOSURE policies have become standardized – they have general terms and a schedule that sets out the specifics of the transaction that is covered – although some limited negotiation is possible.

International syndicated loans may be governed by English law; however large bilateral deals may be documented under Chinese law (although still based on LMA-style documentation). SINOSURE requires arbitration as the dispute resolution forum in its policies.

9. Are loans structured on the basis of a payment cascade as per international project finance?

Bilateral loans are structured on more simple corporate lending terms, particularly where there is a strategic interest for China in the project/host country. A parent company guarantee is typically required on this structure.

If the Chinese financing is purely a commercial transaction with no strategic interest, we have seen a move towards seeking more international project finance norms. We are also seeing Chinese banks lending on a bilateral basis on day one structure deals on more Western bank norms in order to be able to allow syndication if required – we are seeing a greater need/desire for syndication at present.

When Chinese banks fund as part of a wider Western bank syndicate they will expect to share in the full suite of project finance structures and security, including payment cascade and modelling mechanisms.

10. Will Chinese banks instruct their own technical adviser or is all technical due diligence done in house?

The Chinese banks adopt more of a high level approach to the technical due diligence. Typically the level of technical due diligence required by Chinese banks is more limited than that carried out by Western banks. Often the banks’ internal personnel will visit the relevant project asset/site and agree the commercial deal as the technical due diligence is carried out on site.

Chinese banks will also often rely on a borrower’s technical adviser reports, with or without specific reliance letters.

11. What Chinese approvals are required?

Other than internal authorizations (e.g. credit committee/board approval), no external approvals are required for enabling Chinese bank/ECA to grant loans to finance international projects.

Chinese outbound approvals have moved from a strict approval process, increasingly to a filing process, however, in practice outbound investments still require approval. These are:

- NDRC, SASAC and MOFCOM approvals/filings will general be required on the equity component; and

- SAFE approval will be required where any domestic assets are offered as security for the financing.

In relation to SINOSURE approvals, the process of getting a policy has become slower. Although obtaining an initial response on underwriting from SINOSURE can be relatively quick – within a week of SINOSURE receiving a complete file – the full process can get very bogged down as the underwriting request is processed through MOF, and even more so if it has to go to the State Counsel. The process takes a minimum of three to six months to complete, and we have seen up to 18 months on a recent deal – despite rumors that the process is being streamlined, it appears to be getting slower.

The length and relative opacity of the process form the basis of negative comments about dealing with SINOSURE and Chinese banks.

12. What qualifies as ‘China content’?

The China content requirement is somewhat opaque, but looks to the outward level of goods/services originated in the PRC or otherwise eligible for SINOSURE cover or determined by SINOSURE i.e. if the EPC Contractor is Chinese but subcontracts to a non Chinese entity and/ or sources relevant equipment and supplies form outside China, this may breach the China content requirement. Ultimately sign off must be sought from SINOSURE up front, with the risk then to the Chinese bank and EPC Contractor going forward, (i.e. no event of default under the loan agreement for breach of China content, and an obligation on the EPC Contractor in the EPC Contract to ensure compliance with China content).

Accessing Chinese Capital for Belt and Road power projects

The BRI is the flagship policy of the Xi government. It is a blueprint for the development and integration of more than 60 countries and aims to link developed Europe with developing Eurasia, Asia and Africa. The Belt and Road region encompasses more than 70 percent of the world’s population and more than 50 percent of the world’s gross national product. Importantly, to underpin the Initiative, China has allocated a stimulus package estimated at between US$1.3 to US$3 trillion.

For investors looking at emerging market opportunities presented by BRI cannot be ignored. Not only are Chinese lenders one of the few major sources of capital for projects but their capital can come with a partial fix for political risk – the key obstacle for projects in the region. In addition the approach of Chinese EPC Contractors and their kit is well suited to the BRI.

In recent years the BRI has moved as a result of international criticism. It has become lower profile and there is an increasing focus on ensuring quality projects are built and for the involvement of non-Chinese capital.

Tapping Chinese capital can be difficult. Negotiations with Chinese banks and EPC Contractors can be drawn out. Being the sole foreign investor surrounded by China INC – a semi homogenous group of state-owned EPC Contractors, banks, ECA and sponsors, can be daunting. Yet a foreign investor that can navigate through is potentially unlocking a key foreign source of capital and equipment for major projects in difficult jurisdictions over the next 15 years. In this guide we look at how.

The place for power in BRI

The Belt and Road Initiative has both implicit and explicit aims and objectives and it is important to understand both, to assess the importance of the energy sector for the Initiative.

The explicit aims of BRI are well documented – to stimulate development of the West of China, increase economic prosperity along the trade routes to Europe, increase integration between China and its neighbors and support domestic security by diversifying the sources of imports. However, it is the implicit aims that will be key to the roll out of power. China hopes to use the BRI to stimulate demand for Chinese industries facing domestic oversupply and create new markets for its goods and services. It ultimately hopes to see its companies use BRI as a stepping stone into the more developed markets they have struggled to access.

BRI: Overcoming domestic power challenges

Chinese power sector companies face both local and international challenges. Coal is in decline, as China agrees to international commitments to reduce emissions and imposes domestic restrictions to address pollution. Solar manufacturers face the threat of anti-dumping investigations in Europe and the US and the prospect of limited growth in their traditional European markets. Chinese wind manufacturers have persistently failed to access developed renewables markets because of technology and track record concerns and have been reliant upon a now saturated domestic market to survive.

The BRI Initiative should create a range of new markets that are ideally suited to the kit, EPC Contractor and finance package that China offers. There are significant energy deficits – Pakistan, India, Myanmar, Indonesia, the Philippines, Bangladesh all operate with thin reserve margins that see frequent brown outs. Developers are price sensitive and demand only adequate, but not optimal plant availability and performance commitments – which is well suited to the strengths of Chinese kit. Most importantly, the key obstacle to development is finance, which Chinese EPC Contractors can bring with them.

BRI: Overcoming political risk

The most significant obstacle for BRI investment is political risk. In recent history, Indonesia, Pakistan and the Philippines have defaulted or re-negotiated PPAs, the Mongolian, Sri Lankan and Myanmar governments have walked away from Chinese funded projects and the Pakistan government is currently being sued for default under the sovereign guarantee that backs the local PPA.

For Chinese lenders and in some cases sponsors political risk is passed onto SINOSURE as we discuss in further detail later in this guide. However, the BRI in itself reduces political risk, for China provides funding with the weight of the Chinese government behind it. This adds a political dimension into any default. Other measures are also being put in place, and for example in Pakistan this takes the form of a collection account which Chinese projects can tap in the event of default. Similar mechanisms may well be established in other countries.

Steps to accessing Belt and Road capital for power projects

The BRI could see up to USD1.5 trillion invested in the 60 countries that comprise the BRI. This will make China the largest funder of power in the region.

The sweet spot for Chinese banks, EPC Contractors and equipment suppliers, is difficult jurisdictions like those that make up the BRI – in these countries Chinese pricing is competitive, funds are deployed quickly and importantly, Chinese capital comes with a partial fix for host country political risk. For any investor in emerging power markets, Chinese capital cannot be ignored.

1. Is your target country part of the Belt and Road initiative?

Chinese diplomats have promoted an all-encompassing definition of BRI that takes it into Australia, South America and the UK. The diplomat’s version avoids offence but it does not accurately describe where Chinese capital is going – which is to a narrow band of Asian, Eurasian and African countries. The ideal host country for Chinese capital is core BRI, maintains a good relationship with China, has relaxed labor controls that allow the deployment of Chinese labor and is preferably one that SINOSURE is not overexposed to.

2. Is your target country open to Chinese investment?

Some countries continue to be sensitive to investment by Chinese companies, particularly SOEs. Consideration will be needed to understand the additional scrutiny from foreign investment approval authorities that partnering with a Chinese company may bring – particularly as any BRI partner will be state-owned.

3. Is there a tight bid timeframe?

The more international Chinese companies can meet tight bid timelines, less international Chinese SOEs find them more difficult. Less international Chinese SOEs find them more difficult. In addition to the outbound approvals regime, Chinese bank support is also a frequent source of delay – terms sheets and commitment letters can be pulled together quickly but credit approval can take time.

4. Can you accept a minority shareholding?

The typical opportunity open to a foreign investor looking to tap BRI capital will come with a sponsor role. A foreign investor will not be able to take key EPC, sub-contractor or supplier roles because the project would then fail China content requirements. Generally, the Big 5 Chinese utilities will need to be the majority shareholder, but if your partner is a Chinese EPC Contractor or turbine/panel supplier you may be able to negotiate a majority shareholding.

5. Identify your Chinese EPC Contractor: Your key route to Chinese banks

The EPC Contractor, not the borrower/sponsor, is the Chinese bank’s customer. That means you need the EPC Contractor to secure finance on attractive terms and to overcome negotiation obstacles. You should establish early on the substance to Chinese finance support, as EPC Contractors can make rash promises around finance when securing an EPC mandate. Investors should be cautious around promises of concessionary terms and you should check the bank’s position on recourse to sponsors and change of control. Key points should be negotiated up front and ideally, a finance terms sheet stapled to agreements with the EPC Contractor.

6. Maintain competitive tension to manage execution risk

Execution risk tends to be higher when foreign companies partner with Chinese companies. Negotiations drag on, agreed positions are re-opened, requirements for recourse to the sponsor are raised each time a new obstacle is encountered and outbound and credit approvals fail to materialize. A key to managing execution risk is to maintain competitive tension from a non-Chinese EPC Contractor for as long as possible.

7. Understand your partner’s approvals

The Chinese outbound approvals and Chinese bank credit approval processes are not well understood. Carefully managed, the risks these approvals present are minimal. The key is to understand, whether your partner requires outbound approvals or simply outbound registrations, whether transaction documents need to be conditional, when approvals will be obtained and be aware of problems as early as possible. Ideally, you should have a representative on the ground in China to manage this risk.

8. Do not expect full information

You will be surrounded by Chinese kit, EPC Contractors, Chinese debt and Chinese export credit cover. Information flows freely within your group of China Inc. partners but it does not always cross to you. The key is to ensure your local team is linked in to the information flow and to realize that information passed to the EPC Contractor invariably finds its way to the rest of China Inc.

9. Keep documents and structures simple

The importance of keeping documents and structures simple and following established precedents used by Chinese investors on similar projects cannot be over-emphasized. Your partner will generally need board, shareholder, credit, SASAC, NDRC, MOFCOM and SAFE approvals or registrations. The credit departments of the Chinese banks in particular are the busiest in the world. A simple structure that follows established precedents will be approved more quickly than a new one.

10. Is there sovereign support for the PPA?

Chinese banks require SINOSURE cover in order to fund and SINOSURE generally prefers to sit behind a sovereign guarantee of the PPA offtaker obligations. Chinese power projects in difficult jurisdictions have generally had sovereign support for the offtake. Recent Chinese tenders in Pakistan and Indonesia are testing this requirement, but in any event, strong sovereign support for the offtake will mean easier approvals.

11. Can a Chinese PCGB enforce a Chinese PCG?

Foreign investors tend to over-emphasise enforcement risks when dealing with a Chinese EPC Contractor. Your EPC Contractor’s parent company guarantee will invariably be with a mainland Chinese SOE probably based in Beijing. That means in the event of a dispute, your Singapore, London or Hong Kong arbitration award may ultimately need to be enforced in courts in Beijing. The PRC has introduced procedures to ensure that such awards are readily enforced in China, and in practice this should usually be the case. You should note that because of Chinese rules on guarantees, rather than being structured as a parent guarantee in many cases the parent is bought into the EPC Contract so that they are jointly and severally liable with the EPC Contractor. This avoids use of the word ‘guarantee’ which is problematic for SAFE registration.

EPC contracts with Chinese contractors

Chinese EPC Contractors or Chinese equipment suppliers are often the borrower’s first introduction to Chinese sources of finance. The major advantage of a Chinese EPC Contractor is that not only will they be able to offer to provide a complete Engineer Procure Construction package providing machinery and equipment (usually on economic terms), but also access to the funds from Chinese Banks to ensure that the project can be implemented.

This was a welcome relief to projects which found their project finance backers disappearing during and following credit crunches.

Negotiating with Chinese EPC Contractors and suppliers (usually SOEs) is a markedly different experience to negotiating with a non-Chinese EPC Contractor.

An international outlook

Chinese EPC Contractors are becoming increasingly international in their outlook and we now encounter them working and soliciting for work throughout Africa, South America, Central Asia Russia and other emerging markets in the BRI regions. This means that the Chinese EPC Contractors are familiar with international forms of construction contract. Indeed, there is a generally held view that the FIDIC forms of contract, particularly the FIDIC EPC Contract (the Silver Book), are de facto acceptable for major construction and engineering work. However, the reality is that like their non Chinese competitors, Chinese EPC Contractors will still require amendments to the standard risk allocation in the FIDIC form (and other international forms) of contract.

Key areas of risk

Chinese EPC Contractors are not a homogenous group. They are fiercely competitive amongst themselves and have varying degrees of experience and government and lender support. Some general points are set out below. One point to note is that, because finance is tied to the EPC Contractor, the Chinese EPC Contractor can go into EPC Contract negotiations in a strong position.

Ground risk and permitting

The customary international negotiating philosophy is that risk is best placed with the party best placed to manage it. Although the Chinese EPC Contractors will accept this philosophy, some also consider that a risk should stay with the party that has the most information in relation to that risk. For example, the crucial ‘ground conditions’ risk and local permitting risk is often rejected by Chinese EPC Contractors. However, with considered negotiation the Chinese EPC Contractors will accept at least a share of this risk. Any risks retained by the borrower undermine the lump sum price concept and mitigation strategies will need to be put in place.

Design risk

There are other key risk allocations where a borrower needs to take care that the fundamental risks in an EPC contract, such as the fitness for purpose design risk (which assures delivery of a working asset at a fixed price), are not eroded. Chinese EPC Contractor’s usually seek to develop the design in stages before they will commit to a lump sum price. Alternatively they will commit but they will seek to include provisions that permit them to revisit the price as the design develops. This should be resisted as it completely undermines the wholly lump sum price concept.

Delay risk

The Works must be completed within a specified period. If they are not completed the EPC Contractor should be liable for delay damages at a daily rate equivalent to the Employer’s losses (which may be loss of profit and/or losses the Employer is liable to pay to third parties for failing to meet the Employer’s commitments). The EPC Contractor will usually insist on a cap. Chinese EPC Contractor’s know the international market and they resist strongly any attempt to have a cap towards the high end of the market.

The EPC Contract should provide very limited and specific grounds when the EPC Contractor is entitled to an extension of time and additional costs. The usual international standard forms must be restricted in this regard. The borrower should push for the Contractor to provide a performance bond to secure the performance of these obligations.

Performance risk

The EPC Contractor should provide certain performance guarantees for the Works performed which, if not achieved, will provide the Employer with the right to claim performance damages. The EPC Contractor will usually insist on a cap based on the Contract Price. These require careful consideration as they will reduce the period for which the Employer will be compensated for the reduced performance of the Plant.

Where the Plant Works when complete do not achieve a certain minimum threshold of performance then there should be a right to reject the Works or require the EPC Contractor to pay buy down damages reflecting the reduced value of the Plant. Chinese EPC Contractors strongly resist these provisions. These obligations are secured by a warranty bond (or a stepped down in value performance bond).

For the above reasons the Employer must give careful consideration to the testing requirements. The EPC Contract must be carefully worded to ensure that the EPC Contractor is not protected by the performance damage caps if the Works are not built to achieve the required operating performance standard. We would usually recommend that the testing for “taking over” (as opposed to final in operation performance guarantee tests) are sufficiently onerous. This would then mean that the testing is secured by the usually larger performance bond.

Defects liability may be secured by a retention bond. However in our experience, Chinese contractors are reluctant to offer this type of security or even cash retention.

Other relevant issues

EPC contracts generally place a large degree of flexibility on the EPC Contractor to source material and equipment. Given the ‘China Content’ requirements of the SINOSURE ECA cover, it is important that the risk of compliance with these requirements is placed firmly with the EPC Contractor. Borrowers should consider the likely consequences of breaching the China Content requirements under the finance agreements and how the EPC Contractor can be made to pay losses to cover these consequences.

It is also important that the borrower remembers that during negotiations the Chinese lenders are unlikely to act in the same manner towards Chinese EPC Contractors (particularly if they are an SOE) as a non Chinese lender would. This is particularly the case if the borrower’s obligations under the funding agreements are backed by a parent company. Western banks will typically undertake a full ‘bankability’ analysis at to the EPC Contract structure and risk profile to ensure that material risks are passed through to the EPC Contractor or other material project parties as applicable. On a Chinese-backed financing, a borrower will need to consider all of the risks that it is taking under its financing agreements and ensure that it negotiates proper back to back protections with its EPC Contractor given that, in our experience, Chinese lenders may approach risk differently to western banks. Where the EPC Contractor is an SOE you should also consider sovereign immunity and enforcement issues.

A Chinese lender and Chinese EPC Contractor/supplier structure can be turned to an advantage to the borrower if the underlying EPC Contract or supply contract is dependent upon the loan being unconditionally available or upon certain agree terms. The incentive to ensure that all conditions are satisfied becomes shared across the borrower, EPC Contractor and Lender.

The PRC stated policy to encourage acquisitions in foreign assets can also give rise to EPC Contractors expressing an interest or requirement that it should be the offtake agent for the ultimate product from the project. Unless the offtake terms are highly advantageous, this should be resisted as ultimately these terms could become the EPC Contractor’s leverage if claims arise during construction.

Do the Chinese institutions offer project finance?

Every deal does have its own history. However, there are certain themes:

- In most cases the Chinese bank does expect recourse to the parent company.

- Don’t assume that the guarantee will fall away on construction completion.

Recent themes include:

- More reference to traditional project finance ratios – DSCR and LLCR.

- Far more intense scrutiny of the financial strength of the parent support. This has led to requests for a suite of cash flow to debt tests and even restrictions of the operations of other material subsidiaries. In some cases this has led to the transaction operating as a co borrowing and thus making the terms of the transaction unattractive.

Finance structures

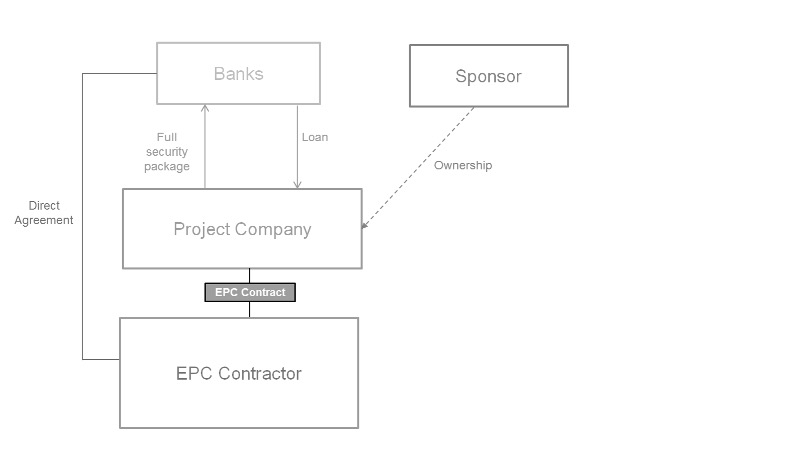

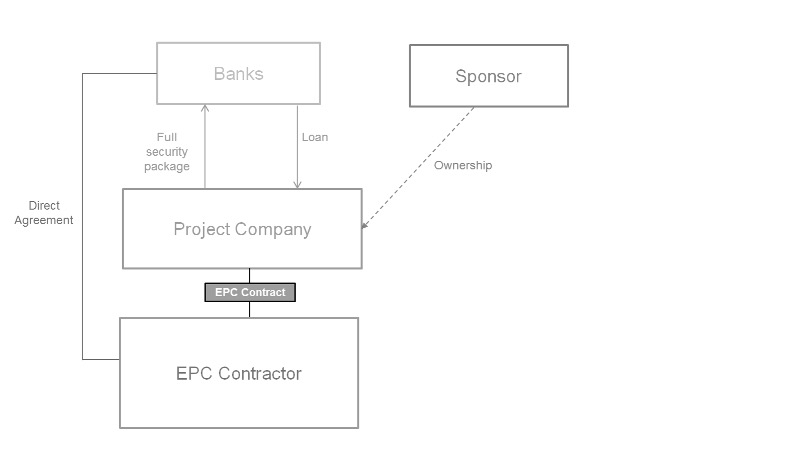

Typical project finance structure

Risk allocation under project finance structure

EPC contract

There is a multitude of ways in which the construction arrangements for the development of a project may be agreed and documented, but many projects are built on a turnkey basis, commonly by way of an engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contract. The sponsors (via a special purpose vehicle project company) will generally seek to shift as many of the completion-related risks as possible onto the EPC Contractor, such that the EPC Contractor is responsible for constructing the plant by a fixed time and for a fixed price such that the plant, once complete, will perform to the prescribed specifications.

Loan agreement

The loan agreement governs the contractual relationship between the banks and the project company. The core obligations for the lenders to lend to the project company and the project to repay the debt are supplemented by a number of protective and administrative provisions dealing with conditions precedent, representations, covenants, events of default, agency mechanics and dispute resolution provisions. Project financings are increasingly complex and expensive and in many cases involve multiple tranches of debt from a number of different lenders or lender groups. In these multi-sourced financings, it has become customary for the provisions which are common to each tranche of debt to be set out in a common terms agreement..

Documentation

A typical project financing structure will include the following key documentation:

- Finance documents (including direct agreements)

- Security documents

- Sponsor support guarantees

- Project documents, including concession or implementation agreements, supply and offtake arrangements.

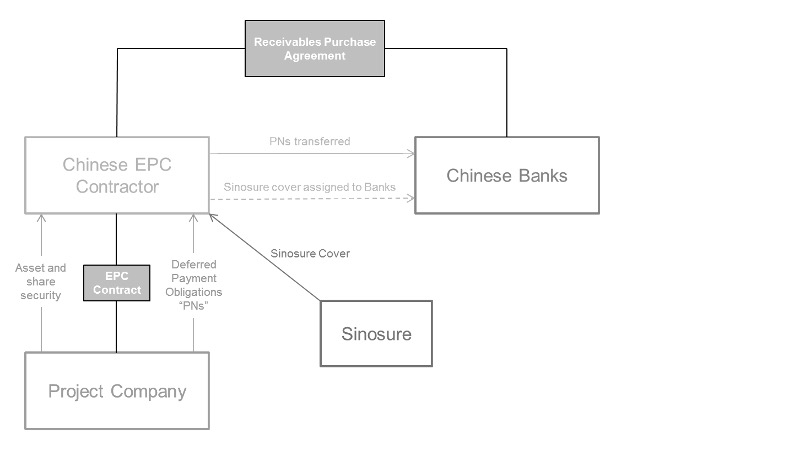

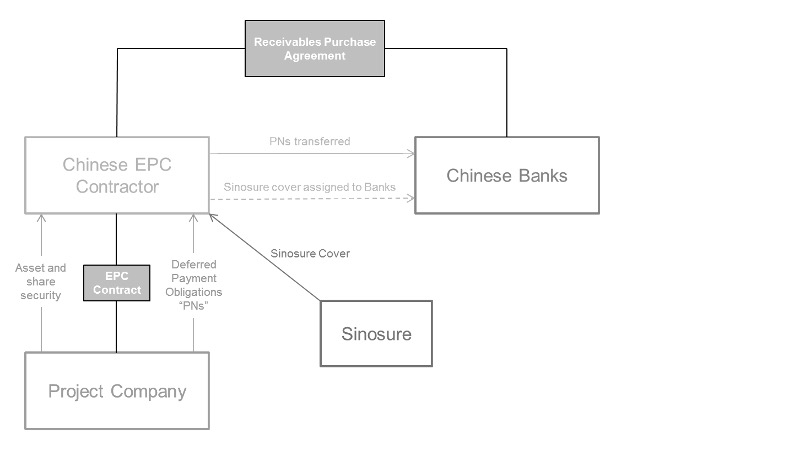

Promissory notes

Basic promissory note structure

Risk allocation under promissory note structure

EPC contract

The EPC Contract is a fixed price contract, and the fixed price includes the financing premium or discount rate, as applicable. The project company is typically required to provide an advance up-front payment equivalent to 15 percent of the EPC fixed price as an interest-free loan for mobilization and design. The issue then turns on whether the EPC Contractor has the capacity and willingness to fund the construction pending the availability of the financing.

Receivables purchase agreement and SINOSURE cover

SINOSURE will not cover the whole project cost; instead, it will typically cover 70 percent of the financed amount. The remaining 30 percent of the risk may be absorbed by the EPC Contractor, who offers collateral to the Chinese banks. This in effect means that there may be little real exposure for the Chinese banks with the result that they may adopt a more limited approach to diligence (technical and legal) than commercial banks would do on non-Chinese project financings.

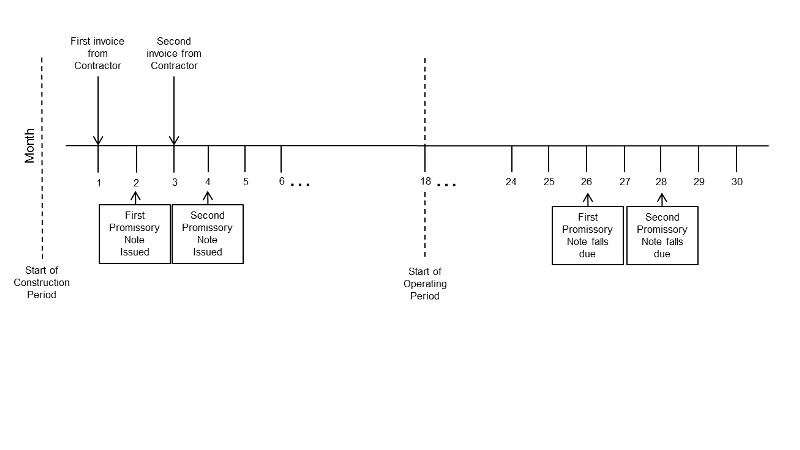

Tenor and repayment

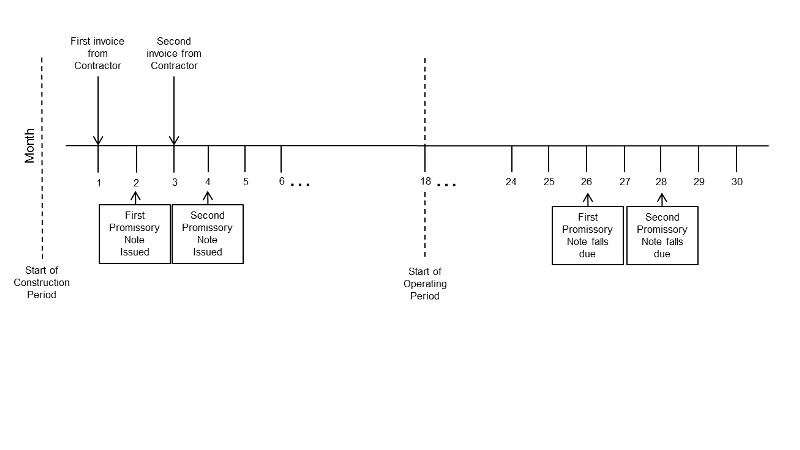

The date on which each promissory note is issued will be determined by the terms of the EPC contract. If the EPC Contractor is issuing invoices monthly, then a new promissory note will be issued each month. If 30-day payment terms apply, each promissory note will be issued within 30 days of the invoice date. If the EPC Contractor is issuing invoices against agreed milestones, then a new promissory note will be issued when each milestone is achieved.

Example: each promissory note being repayable 24 months after issue.

Repayment risk

Where promissory notes are issued to be repayable within a two-year period, the debt will become due within two years of construction commencing and the same will amortize during a period equivalent to the construction period. However, if construction is delayed, payments under the promissory notes will become due despite the absence of offtake product from the project. Even if construction is completed on time, the debt burden would likely be too onerous due to, for instance, ramp up. Therefore alignment of the EPC Contract payments with a preferred debt repayment profile is critical.

Chinese banks and SINOSURE have stated on recent projects that they may seek approvals for extensions to repayment deadlines closer to the repayment date of the promissory notes, but are reluctant to agree this up-front. This creates a clear risk for the sponsor which can be mitigated by certain solutions. First, risk may potentially be transferred to the EPC Contractor through automatic extension mechanisms, whereby certain circumstances may trigger an extension of the due date for repayment. Second, repurchase obligations could be imposed on the EPC Contractor in relation to the promissory notes held by the Chinese bank with replacement promissory notes would then be issued by the project company. Points for consideration include how the EPC Contractor will fund any such repurchase

In-Country considerations

- There may be limits on the levels of cover that SINOSURE can provide in a given jurisdiction and therefore the total value of EPC services the project company can procure.

- The structure of the transaction can be complex and will need to be explained to local partners and/or the state shareholder, if any.

- Exchange control restrictions may limit the funds which can be used to repay the promissory notes.

- The use of promissory notes may not be recognized as a matter of local law – local law advice will be required to confirm this.

- There may be alternative options to a promissory note: for instance, assignment of the EPC contract or a payment order acknowledgment in lieu of a promissory note.

- Consideration surrounding the potential to set-off against obligations owing under a promissory note.

- The restrictions or prohibition on holding local law security on behalf of other parties pursuant to local law. Further, local law corporate benefit issues may arise.

Documentation

There is, in general, less documentation under a promissory note structure as compared to a typical project financing.

EPC Contract

This agreement is derived from the FIDIC standard form contract, and will also have a greater focus on risk allocation and customized payment mechanics between the parties. There is likely to be less leverage to negotiate with the EPC Contractor given that customary ‘bankability’ issues do not apply as readily as on a more typical project financing.

Receivables purchase agreement

This agreement is short-form as compared to a loan agreement. It should be noted that the project company will not be a party to this agreement; there is no privity of contract between it and the Chinese banks. The project company therefore also has limited ability to influence which risks are placed with the EPC Contractor. Consideration will also need to be given to repurchase events and any alignment with event of default.

Security documents

Under these documents, onshore and offshore security will be granted by the project company in customary form.

Parties that are familiar with the structure

- NFC

- SINOSURE

- China Exim

- ICBC

In our experience, there is a much better prospect of raising Chinese finance if there is adoption of a structure which the institutions above are familiar with.

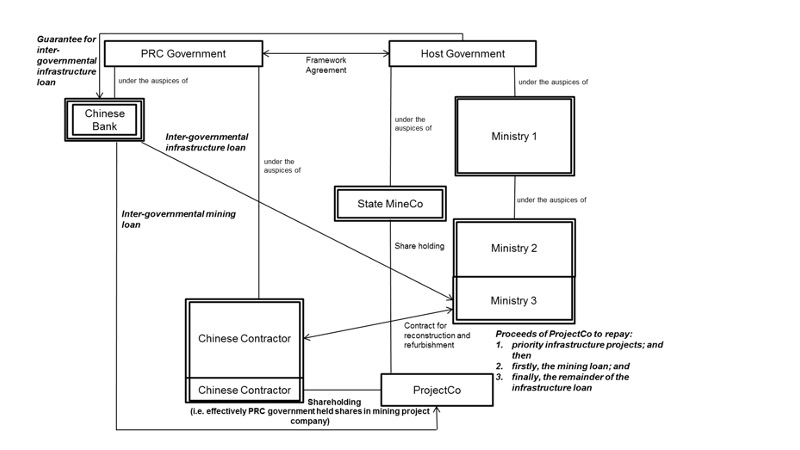

Inter-governmental lending

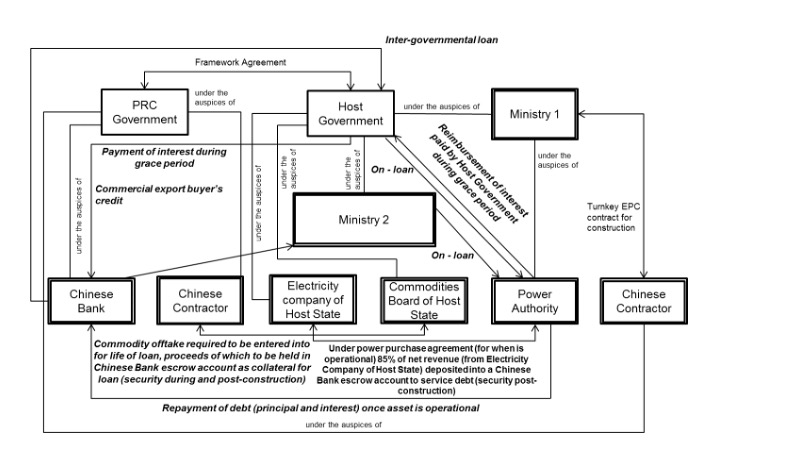

Example of an unsecured soft-comfort inter-governmental lending

Risk allocation under an unsecured soft-comfort inter-governmental lending

The inter-governmental loan between the Chinese bank and sovereign wealth fund is on-lent to the Project Company where the project satisfies the applicable Chinese content requirements for a project which is already a ‘producing/production asset.’

There is generally no asset level security that is taken the banks. Rather, the soft comfort for the Chinese banks is provided by:

- Sovereign wealth fund (as the intermediary lender) has recourse to a parent company guarantee given by the Project Company’s parent; and

- The parent company of the Project Company, the host government entity, the sovereign wealth fund and Chinese bank are all party to a Framework Agreement to establish privity of contract and key principles to govern their respective relationships throughout the development of the project.

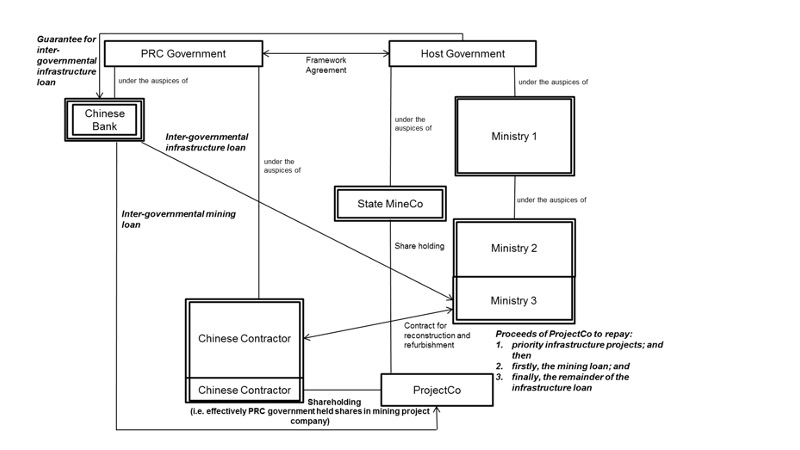

Example of a mixed unsecured medium-comfort inter-governmental lending

Risk allocation under a mixed unsecured medium-comfort inter-governmental lending

Part of the inter-governmental loan between the Chinese bank and applicable ministry is on-lent to the Project Company (the ‘soft loan’) and part ECA-backed project finance loan is lent directly to the Project Company (the ‘hard loan’) where the project satisfies the applicable Chinese content requirements.

In the example above, the funds from the soft loan are applied towards the development of infrastructure for a mining project and the funds from the hard loan are applied towards the development of the mine itself.

There is generally no asset level security that is taken the banks. Rather, comfort for the Chinese banks is provided by:

- Direct recourse to the host government under a sovereign guarantee for the soft loan;

- Access to the shareholding in the mining Project Company through the PRC Government (via the SOEs);

- The hard loan (non-guaranteed) is repaid ahead of the ‘soft loan’ (guaranteed);

- The PRC Government entity and the host government entity are party to a Framework Agreement to establish the key principles to govern their respective relationships throughout the development of the project.

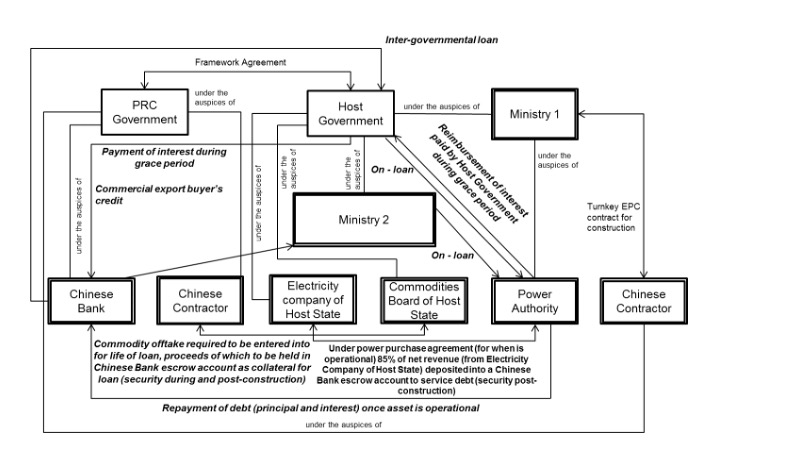

Example of a mixed secured high-comfort inter-governmental lending

Risk allocation under a mixed unsecured medium-comfort inter-governmental lending

The inter-governmental loan is on-lent to the Project Company where the project satisfies the applicable Chinese content requirements for the commercial export buyer’s credit loan.

There is generally no security that is taken by the Chinese bank over the project assets during the construction phase but there is no construction risk for the Chinese bank given it has third-party asset security over the proceeds of commodity sales for the life of the loan.

Post-construction, the Chinese bank takes security over receivables from the project and continuing third-party security over proceeds of commodity sales.

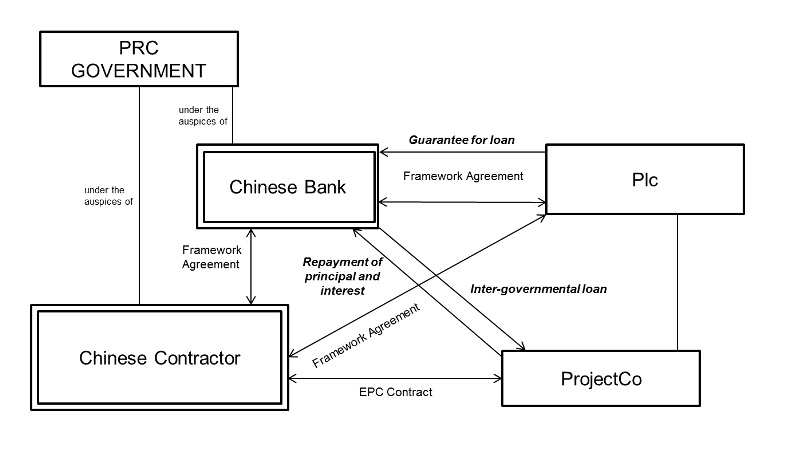

Private lending

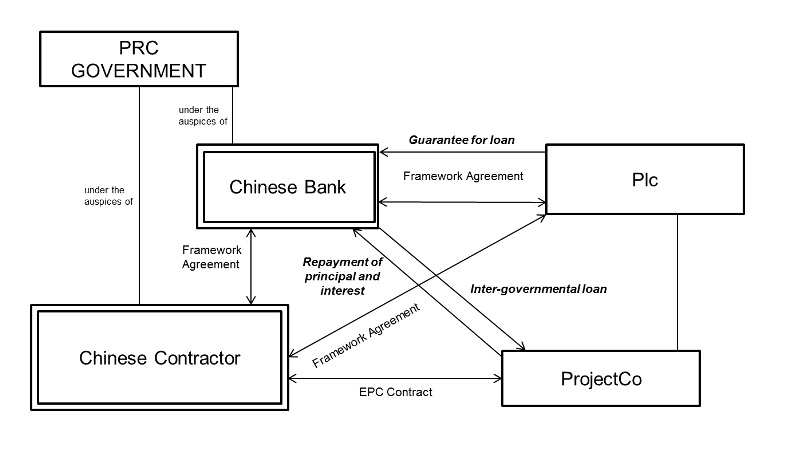

Example of an unsecured medium-comfort private lending

Risk allocation for unsecured medium-comfort private lending

A direct loan is made to the Project Company where the project satisfies the applicable Chinese content requirements for the Project Company to fund the greenfield project.

There is generally no asset level security that is taken the banks at the outset of the transaction. Rather, the Chinese banks take comfort from:

- The Chinese bank has recourse to a parent company guarantee given by the parent company of the Project Company; and

- The parent company of the Project Company, the Chinese EPC Contractor and Chinese bank are all party to a Framework Agreement to establish privity of contract and key principles to govern their respective relationships throughout the development of the project.

Offtake Agreements

Typical project finance offtake arrangements

In most projects, the principal means to manage revenue risk is through the offtake arrangements. A project may not necessarily require a long-term, committed offtake agreement if its product is only capable of being sold on the spot markets, but in most cases lenders will consider such arrangements as integral to the ‘bankability’ of the project and will expect committed offtake arrangements for a period which exceeds the tenor of debt.

The market into which a particular product is sold will determine the structure, pricing arrangements, covenants and credit support required to be given by the offtaker to the seller (typically the Project Company). For example, the creditworthiness of a single offtaker for a power project will be critical to the viability of the project as there may be no market if that offtaker could not purchase power for any reason.

For a natural resources project which produces a high-quality commodity which is readily tradeable, the issue of managing logistics, interface with local government, transfer of risk and title and access to market is key. Offtake agreements are therefore ultimately structured around the commercial requirements of the parties and are often heavily negotiated.

Issues which typically arise (as distinct from a Chinese-backed financing – see below) include:

1. What is the nature of the offtaker’s commitment to purchase

The offtake contract may be structured as a marketing arrangement or as an option to buy but it will more likely require a firm commitment to take product up to (and usually past) the final maturity of debt. The offtaker may commit to purchasing a specified quantity of the commodity (or a percentage of total production) over a specified time period. The seller (typically the Project Company) will have a contractual claim for damages against the offtaker if the offtaker fails to take delivery of, and pay for, its committed quantity.

2. Pricing arrangements

Relevant market factors in determining the purchase price payable by the offtaker will include:

- The transparency and depth of the market for the specific commodity

- The reliability of the spot market (if there is one) as a source of value for the commodity

- What percentage of the global, or regional, trade in the commodity is at the spot price.

If the offtaker pays a purchase price which is less than the market price, the discount or margin will depend on the relationship between the parties and their respective bargaining power. This would be the case where, for example, where the offtaker is also a provider of debt or equity financing and the offtake is an upside to such financing.

The discount may take into account additional services provided by the offtaker such as arranging the logistics, as well as other indirect benefits the offtaker may be able to offer such as access to transport links or port capacity. The discount will also be linked to the offtaker’s position in the market for the commodity, for example the offtaker may have access to committed buyers, access to buyers willing to pay a premium for the commodity, or access to a particular pool of buyers which the seller cannot access directly.

The creditworthiness of the offtaker, the agreed delivery profile of the product and the broader context in which the offtake agreement is entered into will influence the method and timing of payments. Prepayments or a letter of credit may be required, particularly in take-or-pay arrangements. Further, the Project Company (and its Lenders) may require the following forms or credit support:

- Robust credit support from parent companies;

- A sovereign guarantee; and/or

- Detailed prepayment terms and secured accounts to ensure that funds are advanced before product is taken or dispatched.

Offtake arrangements in a Chinese backed financing

There are certain similarities in the commercial considerations and structures which apply for offtake arrangements for a typical project finance structure as apply on a Chinese-backed financing.

1. EPC Contractor group entity as Offtaker

In an EPC–led, Chinese-backed financing, the Chinese financiers (SINOSURE and the Lenders) will likely require a Chinese offtaker which in many cases is an affiliate entity to the EPC Contractor. The offtake arrangements may also be a key focus for the Chinese EPC Contractor group because access to product has traditionally been a key driver for outbound Chinese investment policy. As the world's largest importer and consumer of many commodities, China drove a decade-long explosion in prices in the 2000s and is still the key market participant in the raw material trade. As at the date of this document, China has announced domestic capacity reductions and supply side reforms in the production of raw materials which has wider ramifications on the global commodities markets. Chinese companies are however still active in the market for high quality assets and offtake rights on any given project will be an important issue in negotiations for the overall deal package.

Another major reason why a Chinese EPC Contractor and Chinese financiers may require a Chinese offtaker (even if not an affiliate entity) is for ease of upfront deal completion and then expediency of project management and/or disputes once the project in question is operational.

2. Due diligence, documentation and credit support

If the Chinese financiers require a Chinese entity to be designated as the principal offtaker (and for these purposes the offtake arrangements may not be negotiated on an arms-length basis), the documentation needed may be less heavily negotiated and/or less sophisticated than may be encountered on a more traditional project financing. In these circumstances, the diligence required to be undertaken by the Project Company may be less onerous than if the offtakers were a number of local private or quasi-state entities (which is the more likely scenario on a more typical PF deal) where a rigorous credit analysis should be undertaken.

Resource M&A transactions involving Chinese investors

Introduction

Outbound investment by Chinese companies has fallen away significantly over the last four years. There is still a drive to invest overseas but the form is more on ensuring investments are into quality targets.

Due diligence

The prevalence of Chinese SOEs in the resources sector means that resource companies seeking to secure a Chinese investment should be prepared for a substantial due diligence process. Whereas the ready availability of cheap government finance, and the drive to secure resources can mean that SOEs will be more willing to commit to the broad terms of the agreement at an early stage, they will almost certainly be obliged to present a comprehensive study of the investment to the Chinese governmental authorities when they seek approval for the investment and when they arrange their finance through Chinese banks.

Resource transactions are often complex in nature and will involve a broad range of legal issues, including local mining regulations. Therefore, in order to assist a potential investor in understanding the key features of the target’s business and the legal framework in which it operates, the target should anticipate the areas in which the potential investor is likely to be interested, and make initial preparations that will allow it to respond with the required information in a timely and rational manner.

Many SOEs will appoint investment banks and legal advisers to assist them with:

- Investment analysis and modelling issues

- Tax issues

- Structuring advice

- Project implementation and completion

- Due diligence.

Given the complexity of dealing with SOEs, these teams require significant diplomatic, legal, analytical and commercial skills to bring a transaction to a successful conclusion. Our experience is that these financial advisers can be engaged or limited success basis which impacts their scope of work.

Preparatory due diligence issues

At the initial preparatory stage, the target should, in conjunction with its advisers:

- Prepare a comprehensive virtual data room.

- Draft an introductory memorandum on the project and relevant documentation (including details regarding the history of the project/target and background/ reputation of the management teams).

- Be prepared for significant Q&A.

- Put in place a comprehensive confidentiality agreement and ensure all documents can be disclosed.

- Prepare a summary of local applicable infrastructure and mining laws.

- Have infrastructure and mining data and analysis ready for scrutiny.

Legislation

One of the primary areas of concern for a potential investor, and an area in which it is unlikely to have prior knowledge, is in relation to the local infrastructure and mining regulations of the jurisdiction in which the target conducts its operations. Building a team of advisers who can distil the applicable regulations and present them in a clear manner will be important for satisfying the requirements of the potential investor. The most efficient way to do this is perhaps for the principal legal advisers to engage local lawyers and other technical advisers, while retaining oversight of the entire due diligence process. The advice will need to cover both mining codes and infrastructure concessions. This will ensure that the relevant local expertise is used and that it is harnessed and presented in a manner that will assist the potential investor in making its assessment of whether to invest in the target.

Case study: Mining

Key issues for the local lawyers to address will include matters such as the precise ownership of the minerals, whether the State has a ‘free carried interest’ in the target, whether there are any restrictions on the sale of the minerals and what approvals are required for granting mining rights. In addition to those matters, the potential purchaser will also be concerned with the specific mining regulations which provide the detail of the procedures regulating the local mining sector, such as the licences involved, financing issues, registration systems and environmental laws. Legislation relating to surface rights, foreign investment codes, state corporations, company law, localization/empowerment laws, employment law, competition law and planning law will also need to be analyzed. There is clearly potential for a vast amount of legislation to be drawn into the due diligence process for a resource M&A transaction.

The experience of the target’s advisers is therefore invaluable as it will allow the most important areas to be anticipated so that information and responses can be provided as soon as practicable. The target will want to ensure that it does all that it can to progress the transaction as speedily as possible as the complexity of China’s legal environment (discussed below) often slows the pace of cross border M&A transactions with Chinese companies.

An additional factor which can delay completion of the investment is the probable requirement of the key Chinese authorities that all of the conditions precedent to the investment being made, other than regulatory approval, are satisfied before they will even begin to seriously consider the investor’s application for approval. Further, there may well be special legislation or policies that govern investments by SOEs in the target’s own jurisdiction (e.g. the Foreign Investment Review Board in Australia), so it is important for the target to ascertain the nature of the prospective investor at an early stage. These issues may well take time to resolve and must be considered in both the scope and timelines for the conditions precedent. Mining projects are generally subject to a significant number of contractual and statutory requirements, including mining license conditions, farm-in agreements, joint venture agreements and royalty agreements. On a mining transaction the most significant documents in due diligence will be the mining leases/licenses. The forms of mining leases/licenses will differ between jurisdictions – in some jurisdictions most of the provisions are set out in the law, while in others the ‘contract’ contains the bulk of the terms. In any event, the potential investor will need to be informed of certain matters such as the nature of the rights granted (whether this is a concession, a license or some other right), what it entitles the holder to do, what its terms are and under what circumstances they may be terminated. Other agreements made by the target, such as management agreements, offtake agreements, refining agreements, EPC Contractor agreements, insurance and employment agreements will all be of significance to the potential investor. The ability of the target to have accurate information available immediately upon request and in an orderly fashion will again assist in the speed and success of the due diligence process.

It is clear that there is potential for the due diligence process to become a time consuming matter for the target. One method of sharing the responsibility in this regard is to offer that legal opinions from the local law advisers be provided to the potential investor. This will mean that the matters covered by the opinions do not need to be addressed in due diligence. There will obviously be a limit on the range of issues which can be dealt with in this manner, however corporate issues such as the target’s valid incorporation, good standing and share capital history, as well as confirming the validity of the infrastructure and mining licenses involved, may be dealt with by the legal opinions. This can be a useful tool in reducing the scope of the due diligence process and should be considered at the outset of the transaction.

The due diligence process will evidently be a significant issue for both the potential investor and the target. The potential investor, who in the context of the Chinese infrastructure and mining sectors will most likely be a SOE, will need to conduct a thorough due diligence process, and the target will want to ensure that it does all it can to provide a smooth and speedy process in which the potential investor is equipped with the information it needs to gain the necessary approvals and make an investment in the target company. However, there will be other factors beyond the due diligence process which relate to the nature of transacting with a Chinese counterparty in this sector that will be an issue to the target, and which the target will need to be prepared for in order to promote the success of the transaction.

Structure of the investment

A number of Chinese investments have involved the investor taking a minority equity stake in either a listed or unlisted company and, in both cases, the investor will look for significant contractual protection of its minority stake. This will often involve board representation, veto rights on key decisions, information rights and sometimes provisions relating to the eventual exit of the investor.

Chinese equity investments will normally come as part of a “package” of other contractual arrangements. For example, the investor may seek to secure an offtake arrangement from a mine for a certain period of time. The offtake will normally be linked to the investor’s continued shareholding and, given the importance of the offtake to the investment, will often require fully settled offtake terms at the point of investment even though production may be some years away. The investor might also insist on particular debt financing arrangements as a condition to its investment or on securing a particular EPC Contractor to construct the mine.

It is particularly important to understand the source of funding for the investor as this itself may have legal or practical dependencies such as regulatory approval. It is not unusual for funding to be considered by the investor relatively late in the process so investee companies must understand the certainty of the funding arrangements before any reliance is placed upon them. Similarly, we have also seen a significant amount of partnering between SOEs and private Chinese enterprises, with a varying degree of prominence of the SOE. It is important to understand the identity of investors to analyze the regulatory and other approval processes required.

Approval/filing procedures for Chinese companies investing overseas

All overseas investments by a Chinese company will require government approval/filings in China before they are able to be completed. The level and extent of those approvals/filings is largely governed by the type of investor, the location of the investment and by the value of the investment. Further approvals/filings may be required according to the particular circumstances of the investment and the structure of the financing. For example, an investment in a uranium mining company may need additional approvals from the Ministry of Science and Technology. A financing secured over assets in the PRC requires registration with SAFE.

The target company needs to be pro active in understanding the impact of the Chinese approval/filing regime on a prospective investment. There is nothing to be gained by relying on assurances from the investor or its advisers that these approvals/filings are forthcoming and simply insert these approvals/filings in the conditions precedent. Regardless of the contractual legal rights of the parties, the Chinese investor cannot, nor will it, proceed without all the necessary approvals/filings.

China’s best known international enterprises, like Sinopec, Sinosteel, Chinalco, Baosteel, Minmetals, CNOOC etc, are all under the supervision of the central State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC). SASAC was established to hold the Government’s interest in those enterprises and operates, in effect, in the manner of the majority shareholder in listed companies elsewhere. In many cases, SASAC will delegate its authority to the ultimate state-owned holding company of the Chinese SOE to exercise its powers.

SASAC does not generally interfere in the daily operations of the enterprise, nor make commercial decisions for them, but it does have the power to ‘hire and fire’ the enterprises’ senior executives, and it does monitor major investments. As a matter of prudence, we would usually include SASAC approval as a specific condition precedent in any significant investment by a major Chinese enterprise and this will normally be insisted upon by the Chinese SOE (and in fact be required to obtain outbound approvals/filings). In the past, SOEs were able to avoid these approvals/filings by using foreign exchange held overseas and by using their Hong Kong subsidiaries to invest, but this practice has more recently become more difficult.

The approval/filing of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) is the second key approval/filing in satisfying Chinese government requirements alongside SASAC. If the overseas investments involve a sensitive country/district or sensitive industry, NDRC approval will be required. Otherwise, in order to improve the efficiency of investment, a filing will be sufficient. Since March 2018, the approval should take no longer than four months and the filing will take less than two weeks, but these timelines are not always complied with.

Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) approval is also required but is less important than the NDRC approval/filing. Except for investments involving sensitive country/district or sensitive industry, only a filing will be required. Generally if NDRC approval/filing is obtained, then MOFCOM should not be a problem.

Finally, filing from the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) will be required for the conversion into foreign exchange and remittance abroad of foreign currency funds out of China by the Chinese investor. This is straight forward provided SASAC, NDRC and MOFCOM approvals/filing are in place.

In addition to the above where the financing, for example any acquisition financing, is structured so that PRC security is provided, then additional SAFE registrations are required. These registrations have become easier to obtain but there was a period five years ago where they were a cause of significant delays in projects and we have had at least one project that has fallen over as a result of SAFE registration issues.

If the investor is listed in the PRC then material asset restructuring approvals may also be required. These can be complicated and the mainland Chinese exchanges can have unusual requirements in terms of the documents and requirements that must be obtained. Similar requirements will also apply if the investor is listed in Hong Kong, although the process in Hong Kong is better established.

State Owned Enterprises

There is much ongoing debate as to the true nature of China’s SOEs. The enterprises themselves will often vigorously defend their autonomy from government. They will describe themselves as government-owned, yet commercial enterprises and there is no doubt that in our recent experience they are driven by normal commercial performance criteria. There is genuine and occasionally fierce competition between SOEs in China, and it is common for us to be expressly reminded that our obligation of professional confidentiality extends to non-disclosure to other SOEs, despite their common parentage.

If there are collateral conditions to the investment, they are more likely to relate to product off-take contracts. If a Chinese state-owned steel mill is investing in an Australian iron ore project, it will be no surprise to the target if the investor requires guaranteed supply contracts. Indeed, the investor’s capacity to deliver a market for the target’s product is likely to be a significant motivating factor in the target’s consideration of the investment. Care will need to be taken that any approval required from any related party is obtained in those circumstances.

China’s SOEs are not typical international investors. Apart from the approval regime to which they are subject, SOEs are managed by a strictly hierarchical management structure which can be frustrating for target companies. Lines of authority are not always clear. The investor’s decision making criteria may not always be clear, nor necessarily motivated by profit alone. It may be subject to longer term goals than those which are apparent to the target. It is critical therefore that target companies familiarize themselves as much as possible with the prospective investor’s other business interests.

The formal signing of investment documents, whilst likely to be accompanied by much ceremony, is rarely seen by the Chinese investor as an end in itself. Rather, it is a milestone on an ongoing journey between the parties; a statement of the parties’ intention at the time. Experienced target companies will both expect, and prepare themselves for, renegotiations in the future.

Break fees

When dealing with a Chinese purchaser a seller needs to focus in on and understand the purchaser’s execution risk – the risk that the purchaser may not reach completion and be in a position to pay the purchase price. As a general rule, execution risk for a Chinese purchaser is significantly higher than other buyers in the market and arises from a combination of factors. From inexperience completing international transactions, from internal management restructurings, outbound approvals, a lack of certainty around debt funding, an inability to understand and complete foreign approval processes, Hong Kong listing rule requirements around shareholder approvals and even domestic Chinese politics.

In practice, the degree of execution risk varies significantly depending upon the purchaser and will also change with Chinese politics. As at the time of writing, private companies will face difficulties tapping policy bank debt while SOEs will face difficulties obtaining approvals for any acquisition outside their area of expertise, or PRC listing rules for PRC-listed entities (for HK listed entity) and any investor in property will face challenges on a number of fronts. However, in 18 months’ time, there will likely be a very different list of issues to consider. That is why due diligence on the bidding purchaser to understand their internal and external approvals, where they are sourcing their funds from and to generally assess their ability to complete is important.

To date foreign sellers have tended to take a blanket approach to execution risk. The main solution has been a break fee imposed on all Chinese purchasers, even some of the more sophisticated financial investors. Our experience has been that these break fees have ranged from 1.5 percent to 9 percent of the purchase price, with the average being around 3.5 percent to 4 percent. Generally funds are deposited in an escrow at signing and are forfeited if the transaction does not complete as a result of a few limited triggers such as outbound approvals, shareholder approvals or the purchaser does not pay on completion. Some purchasers have agreed broader triggers, such as breach of the transaction documents – for a seller that more effectively captures certainty of funds and also problems arising from the purchaser’s inexperience managing the transaction. Some sellers have even managed to push domestic approval risks onto the buyer and include failure to obtain domestic approvals such as CFIUS and FIRB.

Enforcement issues when dealing with Chinese counterparties

Introduction

As in any transaction, the transaction documentation will need to contain appropriate governing law and dispute resolution provisions to ensure that obligations are enforceable in the event that a party refuses or fails to perform its side of the bargain. A contract with no means by which to enforce the obligations contained in it is little more than a dead letter.

In the vast majority of international transactions, this need for enforceability will (for reasons explained below) result in international arbitration, rather than litigation before national courts, being adopted as the final form of dispute resolution. Arbitration can be adopted either as the sole means of dispute resolution or as the final part of a stepped procedure by which (for instance) there is first to be (as a pre condition to arbitration) an attempt at amicable settlement or a fast track form of dispute resolution (such as mediation).

This article looks briefly at points to bear in mind when choosing between dispute resolution options when contracting with a Chinese counterparty, and looks primarily at how (following the receipt of a favourable award in arbitration) enforcement proceedings may be taken against a Chinese counterparty. An understanding of the risks involved in enforcing international arbitration awards in China is an inherent part of understanding the risk profile of any infrastructure or mining deal involving a Chinese entity, be they a contractor, an offtaker or an investor.

Choice of jurisdiction/dispute resolution procedures

The starting point when considering these matters is the almost universal truth that a non-Chinese contracting party will not be willing to contemplate having to bring a claim in the Chinese courts. This might be for fear of bias among the courts in favor of Chinese entities (although this is not necessarily a fear validly held). More importantly, however, it will be born from a desire to see a neutral form of dispute resolution adopted which does not inherently favor, in terms of culture, language or procedure, either contracting party.