There should always be proper and full engagement by the developer and its in-house engineering team at conceptual design stage. It is at this time that developer requirements should be established and clearly communicated to all relevant parties.

Following completion of conceptual design, developer focus should be on the selection of an appropriate contract delivery structure. These considerations should take place before the commencement of detailed design. Experience shows that detailed design will tend to influence how contract delivery will be structured which will of course narrow developer choice and the opportunity for flexibility in procurement.

As a practice, we expend a significant portion of our time with our clients during this period of project formulation. It is important that the developer achieves its required position with regard to risk allocation and pricing and all potential options should be reviewed and analysed during this predetailed design phase on a cost-benefit-analysis basis.

Experience shows that a lack of detailed considerations at these early stages by the developer and its advisers/ consultants defining the specification and subsequently structuring the contract delivery structure can often lead to problems later. These problems can often strain relations between the developer and the supply chain leading to dispute. Ultimately, the risk to developers arising from a lack of planning is the potential for time and cost overrun risk exposure.

We provide below a high level description of some of the key contract options and issues to be addressed in light of matters already considered in this briefing.

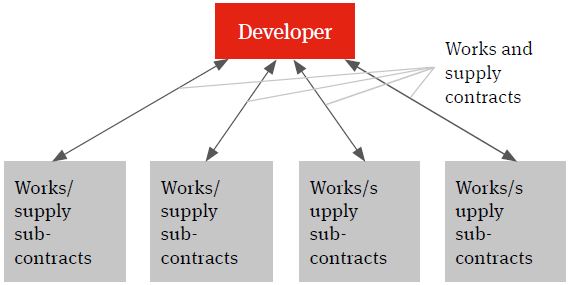

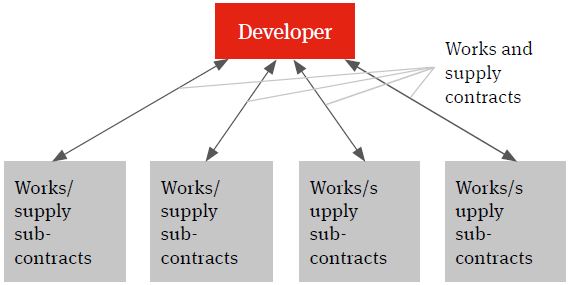

Multi-contracting

The multi-contracting model will see the developer identifying the individual works and supply packages, procuring the contractors and suppliers, entering into contracts with them and managing itself the interface (design, programme, integration etc.) between the different packages and the achievement of the overall global project targets – such as planned budget, planned completion and planned date of full operations (the Key Project Targets).

Figure 1. Multi-contracting solution

There are number of reasons why the developer may choose a multi-contracting solution.

Given the high degree of interface risk involved between the different facets of a typical project in the life sciences sectors, there may be a more limited number of contractors able and willing to assume full risk in delivery of the project on time, on budget and to a required technical and performance specification (often referred to as a ‘wrap’ of construction delivery risk). Contractors prepared to offer this wrap of construction delivery risk may in return include significant risk contingencies in their price for the works. This may impact on the developer’s returns and even the economic viability of the project. In contrast, the multi-contracting option is often seen to offer price advantages.

A multi-contracting approach tends to provide the developer with a degree of flexibility both in design development and in the procurement of the works and supply packages. Where a single contractor EPC solution is selected (see below), the contractor will typically agree to fix its price for project delivery based on known developer requirements at contract signature and there will be little scope for the developer further influencing design direction or procurement choice going forward (at least not without it having a significant price impact for the developer).

If a multi-contracting solution is selected, experience shows that the developer will require an experienced and wellresourced internal team to manage the procurement and the delivery of the works.

It may be the case that such resource and experience is not available to the developer and there may be the need to employ an experienced project management consultancy to act as the ‘developer team’. Obviously, this team should not be left to second guess developer requirements and so there must be clear lines of communication, such that developer requirements and specifications are clearly communicated and understood at project inception and throughout implementation.

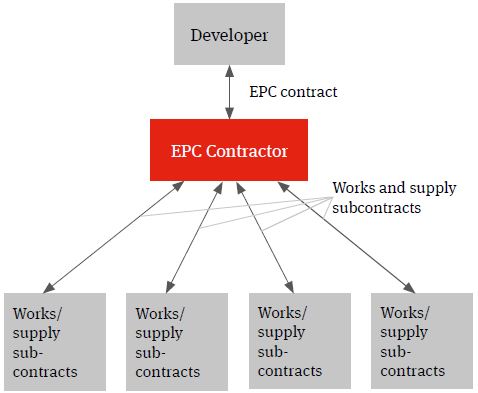

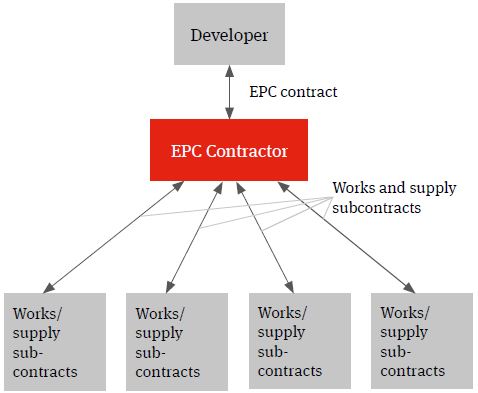

Single contractor EPC

The multi-contracting route can be contrasted with a single contractor turnkey solution under which the relevant contractor will wrap construction delivery risk for a fixed price. This model is often referred to as an engineer, procure and construct (EPC) model.

Whilst the developer will procure the relevant contractor and contract directly with it, the wrap of construction delivery risk being provided by the EPC contractor will (subject to the developer knowing specifications which can be priced by the contractor) typically see it assuming responsibility for identifying the individual supply and works packages, procuring the contractors and suppliers, entering into the individual works and supply contracts, managing the interface risk highlighted above (both practically and from a risk and a liability perspective) and for the achievement of the Key Project targets.

Often, the name on the front cover of a contract doesn’t reflect the content and minor deviations from key requirements can mean that unintended time and cost risk may filter back to the developer. Diligence should be exercised to ensure that the contract delivers the expected risk allocation, so as to avoid nasty surprises for the developer during project implementation.

Figure 2. EPC solution

There are of course a number of hybrid contractual structure models which may also be considered by the developer.

Whilst the multi-contracting solution may give rise to capital cost savings when compared with a single contractor EPC solution, it is likely that greater amounts of risk are retained and need to be managed by the developer.

It is the means by which these risks are managed by the developer that is critical in achieving project success.

The availability of an experienced and well-resourced internal developer team or an experienced project management consultancy will go some way to assisting the developer in managing the retained risks referred to above and which are connected with a multi-contracting solution.

Experience shows however that the ability to manage retained risks can be enhanced significantly through the use of an engineer, procure and construction management (EPCM) contractor. We have seen the benefits that use of an EPCM solution can have in the realisation of process plant infrastructure delivery across a number of sectors for developers procuring infrastructure delivery on a multicontracting basis.

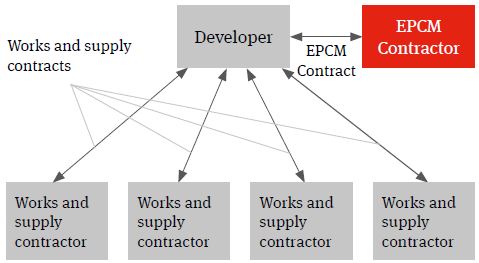

EPCM

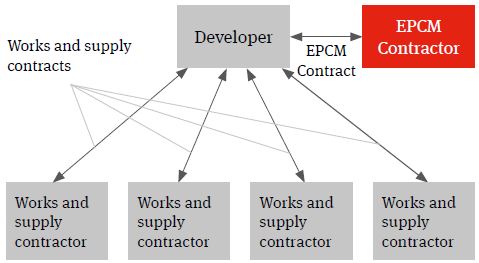

An EPCM contract is essentially a professional services appointment under which the EPCM contractor’s services will usually be limited to the production of detailed design and the procurement, construction management and coordination of the works and services necessary to deliver the project.

It is important to recognise that it is not a contract for the carrying out of construction works.

Figure 3. EPCM solution

The EPCM Contractor will contract directly with the developer and it is usually the developer that contracts with the works and supply package contracts (procured and managed by the EPCM contractor) not the EPCM contractor. The authority of the EPCM contractor to act on behalf of the developer and to manage the works and services will usually be documented in the EPCM contract and acknowledged in the works and services contracts.

Whilst often confused with the EPC contracting solution (mainly due to use of a very similar acronym), the EPCM and EPC contracting solutions are very different in terms of the nature of the obligations undertaken and the risk allocation assumed by the respective contractors. In contrast to the EPC model, which is based on risk transfer and more limited client/contractor interaction, the EPCM ethos is more about collaboration and cooperation and less about risk transfer.

The EPCM contractor will not backstop project delivery risk and, importantly, the achievement of the Key Project Targets. The EPCM contractor will however be responsible for managing the same on behalf of the developer but the levels of liability assumed by the EPCM contractor for failing in the performance of its obligations will typically be more limited (e.g. 10-20% of the EPCM services fee). If there is significant failure in the achievement of the Key Project Targets, the ‘buck’ will ultimately stop with the developer.

Whilst reputation in securing project delivery will be an important factor for the EPCM contractor, the developer will need to consider and implement contractual mechanics to appropriately incentivise the EPCM contractor to effectively and proactively manage and control project delivery and the achievement of the Key Project Targets.

The approach typically adopted under an EPCM solution relies on an incentive structure which provides positive (and sometimes negative) incentives to the achievement of the Key Project Targets and other associated targets e.g. health and safety performance, meeting the EPCM budgeted price etc. These provisions are generally bespoke and may be underpinned by fairly complex calculations but equally can be fairly straightforward depending on the approach preferred by developers.

Since the EPCM contractor will typically set the Key Project Targets and other associated targets through its procurement and programme planning obligations, appropriate due diligence will need to be undertaken by the developer team to establish that these are sensible in the context of the project and the relevant incentive payments/penalties proposed.

EPCM and the management of retained risk

While assistance and support from a highly experienced EPCM contractor will be very important, it will not provide an ultimate backstop for a failure in achieving the Key Project Targets. Since these risks may then ultimately rest in the most part with the developer, it will be necessary for the developer to consider and plan for how these risks will be mitigated and/or managed. The developer should therefore also look to consider the following as part of risk planning:

- hands on management and support by the developer team to assist and direct (as appropriate) the EPCM contractor

- ensuring the terms of the works and supply contracts are robust with all typical ‘on-market’ protections (see below)

- the use of interface management contracts (see below);

- insurance

- enhanced testing of process and product at key interfaces to mitigate hand off risk and its consequences

- access to cash contingencies.

Form of contract

The terms on which the works and services contracts are procured under EPCM or other multi-contracting model will remain very important. Where possible, these should be procured on a fixed price basis and should be on robust terms backed by a comprehensive security package arrangement. Whilst procurement will be led by the EPCM contractor, the developer will want to keep a very close eye on this and the forms of contract used and it would be sensible to include template forms in the EPCM contract terms.

The process plant sector as a whole tends to use an array of different standard form contracts. The most popular, in our experience, include the forms produced by the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE), the forms produced by Fédération Internationale des Ingénieurs-Conseils (the International Federation of Consulting Engineers) (FIDIC) and the forms produced by the American Institute of Architects (AIA). They tend to be known by contractors operating in the sector and tend to be an acceptable starting point, with different ‘books’ being produced for different types of work and pricing structures. It is always sensible to harmonise the forms used across the project such that the different contracts work well together and this will of course also enable more efficient management of the individual packages.

Developers should look to harmonise dispute resolution procedures across the contracts and in particular, to provide for the right consolidate claims to enable it to bring related disputes under the same umbrella to avoid the inefficiency of multiple claims running at the same time on the same or connected issues. This may also be achieved through the interface arrangements described below.

The developer, along with their advisers or the EPCM contractor, may also propose bespoke forms of contract which may be another acceptable starting point. Bespoke forms may however on occasion be viewed with mistrust by contractors and suppliers and may be seen as a venture into the unknown when compared with the industry standard forms identified above. Unless properly managed, this approach could delay the procurement timetable.

An understanding of the risk allocation under the form of contract proposed will be important for the developer and will shape the need (as applicable) for amendments to the contract form proposed.

EPC Islands

Developers may look to establish, where possible, an ‘EPC island’ approach under the EPCM structure. The idea here is that identified and discrete sections of the project will be delivered and ‘wrapped’ by a single contractor and this will assist in reducing the level of interface risk being retained by the developer. This is often seen for key aspects of the process technology or ancillary facilities such as waste water treatment or power.

If an EPC island approach is to be adopted, care should be taken to limit the level of design development in relation to the relevant package(s) during the pre-procurement phase. In our experience, EPC contractors may be reluctant to assume risk in detailed design produced by third parties (i.e. the EPCM contractor), at least not without pricing on a contingent basis the risk of accepting such design. There is of course a balance to be struck between the developer having clarity on the specification required and the exposure it can accept to the cost premium likely to be charged for the EPC contractor in assuming risk in third party design.

Interface management contracts

We have mentioned interface management contracts above in the context of interface risk. The use of these arrangements will represent a fairly innovative approach under which the works and supply contractors on the project (or for a discrete aspect of the project having high degrees of interface) will enter into a multi-party interface agreement.

A ‘collaborative’ or ‘alliancing’ approach has widespread use across the construction industry and is of great value in that it encourages and incentivises cooperation and coordination between individual contractors in the supply chain. The approach advocated here takes the alliancing approach one step further, hardwiring some of the key principles contractually between supply chain members.

An interface agreement should seek to establish how the parties will cooperate with one another, how they will resolve disputes and importantly it will seek to allocate the risk (time and cost) of managing interfaces to the supply chain.

We have experience of successful implementation of these types of bespoke arrangements on high value multicontracting process plant projects and would suggest that they represent a ‘high water mark’ in terms best practice in managing infrastructure delivery under an EPCM contract solution.