Publication

Insurance regulation in Asia Pacific

Ten things to know about insurance regulation in 19 countries.

Global | Publication | May 2016

The former chief economist of the African Development Bank, Professor Ncube, has forecast that growth in Africa will decrease to 4.5 per cent during 2015 and is unlikely to rise to more than 5 per cent next year. This is a consequence of the slowdown in China and the associated end of the ‘commodity super cycle’ that has driven the economies of Africa’s developing countries.

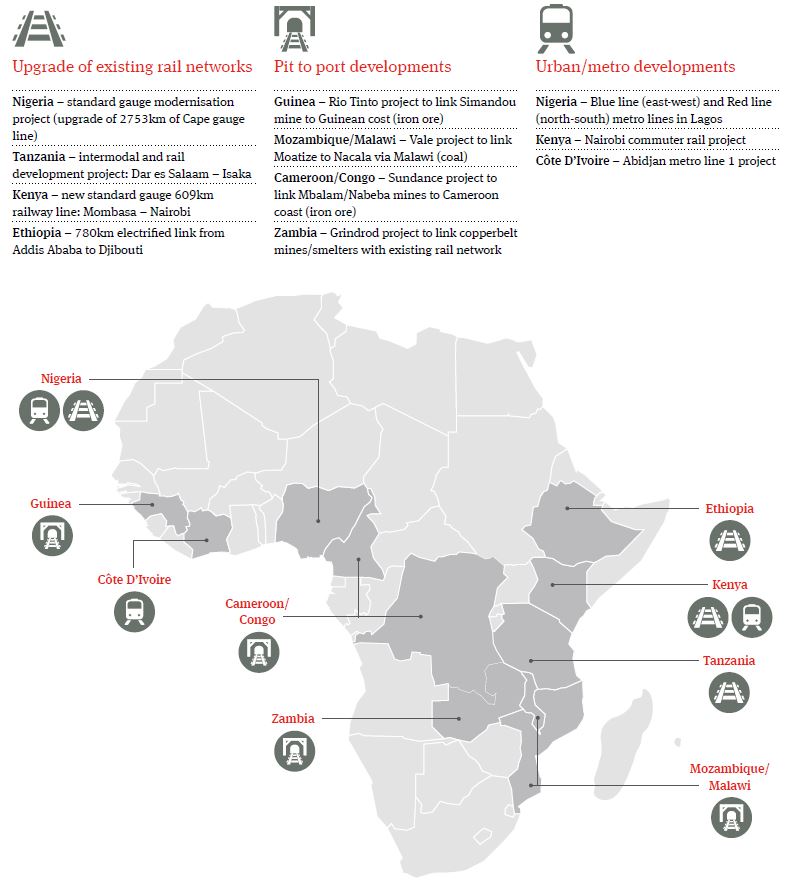

In contrast to this prediction however, the current value of rail projects across Africa is estimated at US$495 billion. This represents a significant investment in a continent where less than 15 per cent of all freight is carried by rail and where urban centres have only just reached the required numbers to make mass inter-city metro transport a viable possibility.

Notwithstanding the gloomy growth outlook, the maintenance and development of transport infrastructure along the entire supply chain of the continent is seen as a pre-requisite to growth in Africa. This is particularly relevant where commodity rich African countries are landlocked, transport costs are considerably higher than in other regions and the transport network is either non-existent, antiquated or in a state of disrepair.

The global slowdown aside, appetite for investment in commercial rail projects remains. In this article we briefly discuss the three main types of rail project and set out, in general terms, the key challenges investors face. Not all of these challenges are peculiar to Africa, but investors who become involved in Africa-based projects have a much better chance of success when guided by local knowledge.

Existing rail networks in Africa are generally in fairly poor condition and require upgrades to rail infrastructure, stations and rolling stock, as well as network extensions, in order to adequately service passenger and freight demands. Often there will be existing state owned entities or other operators in place, and the planning and regulation of the various rail systems may vary in vision, content and implementation. Of course there are some areas, such as South Africa, where there have been well operated and maintained passenger services, regulated to some extent, as well as dedicated lines of high quality for the movement of commodities (a good example being the 861km Sishen- Saldanha iron ore line). In other areas, such as Namibia, local rail freight services have had to contend with a colonial rail infrastructure that cannot provide for extended freight rail services without considerable investment to upgrade the current track. The regulation of the rail system presents its own challenges: rail safety regulators may well be found for passenger rail issues – but economic rail regulators – or even operational regulators – may be needed to control issues such as tariffs, line access and utilisation.

There is also significant scope for confrontation between the state’s operation of rail infrastructure and rolling stock and the requirements of private operators. For example, long-term issues may arise if the operators do not adhere to standards placed upon them by the state, whilst the state in turn may utilise the line in a much less regulated way, leading to infrastructure, maintenance, environmental, health and safety and possibly social issues.

Whilst development of appropriate regulations is a positive step, longer-term investors will want some kind of certainty that this development will not radically affect their investment assumptions. If the cost of complying with new regulations cannot practically be passed to customers, then the investors may wish to look for an appropriate stabilisation regime, either in terms of exemption from application of new laws or a right to be kept in a financially neutral position.

So-called “pit to port” developments may take place outside the regulated networks and often require the creation of new lines. These developments are mostly driven by mining companies or specialist logistics providers with varying levels of government support; there are good examples of major projects (both underway and planned) in Mozambique, Cameroon, Guinea and Liberia, amongst others. Investors in mining projects are used to taking the significant development risk involved in mining ventures and to that extent are also used to taking the risk of developing the associated infrastructure, but where the infrastructure provides a long-term public benefit, for example by opening up potential corridors for other mineral developments, there may be grounds for the government providing a greater level of commercial support, for example, by underpinning part of the debt and/or guaranteeing levels of traffic.

Third-party track access arrangements can be a key issue in these projects. Governments will want to avoid a situation where they have provided a long-term concession to a monopoly user which then effectively locks outs potential opportunities for others by refusing access; accordingly, many projects have built in the concept of an agreed methodology for allowing third party access based on the new users taking on an appropriate share of the initial infrastructure cost. In certain appropriate circumstances the state may also wish to impose a public service (passenger) requirement on the line, however there may be practical limitations to this given the very different requirements of passenger trains and freight trains (in terms of speeds and stopping times).

If a proposed line can practically facilitate other freight and passenger options, this clearly creates efficiencies and reduces dependency on a single commodity. This may be the point to consider whether the rail line can then be spun off as a stand-alone project, helping to develop a new “transport corridor” for the country. This in turn would reduce the financing burden on the mining project which originated the line, but at the expense of creating a dependency to the extent the line falls outside its control.

New metro projects often create their own standalone networks, but these projects can be highly technical, and therefore have their own complications in terms of structuring and funding. The general view is that it is very difficult to make greenfield metro projects self-funding, even in developed countries, and virtually all demand-risk metro projects have failed to meet their original traffic projections. In practice this means that the government would need to retain a significant portion (if not all) of the demand risk to make it externally financeable.

Nevertheless it is possible that this assumption could be challenged by developments in some major cities in Africa, where an urban metro scheme would offer significant time benefits against chronic congestion (where road infrastructure has not kept up with increased private car use), which may mean that passenger numbers may be high enough to secure appropriate financing even on relatively low fares. However, to date there are limited examples of existing urban/metro projects in Africa. The Gautrain project in South Africa provides a good example of a greenfield interurban rapid transit railway system; more recently a new light rail system has been inaugurated in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, being the first project of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa, conceived with the assistance of Chinese export finance.

In most African countries the ‘below’ rail (fixed infrastructure) and ‘above’ rail (rolling stock) assets are owned or controlled by the state, usually through state-owned enterprises. While the state may subcontract certain of its obligations to concessionaires, franchisees, haulage operators or similar entities, funders are for obvious reasons more attracted to those rail infrastructure projects which are guaranteed by the state. Accordingly, the state clearly has the principal role to stimulate ongoing development in the network.

Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) are a means to do this, but have not been as successful in Africa as had been hoped. Where they have been used, the best capabilities of both the public and private sectors have not consistently combined to produce mutually beneficial results. Some private investors are reluctant to commit their resources over the length of time necessary for a PPP to operate efficiently, and another key issue associated with PPPs is the length of time the process can take to produce the public infrastructure required. While politicians are keen to promise and deliver the desired infrastructure quickly, and need privately available skills to do so, the state usually wants to preserve all its decision-making prerogatives. The state may also underestimate the time needed to conduct a transparent and competitive procurement process, as well as the time that private investors need to undertake the appropriate feasibility studies in order to develop a business case and secure all the necessary permits and approvals. This will be exacerbated where the project is greenfield and faces the difficulties involved with accurately predicting the demand risk.

Some PPP projects have been criticised because they have not clearly defined the expectations and roles of the government (and its various departments) and the private participant. The high level of interface with the existing built environment or over a significant corridor means that rail projects can involve a large number of government departments for approvals. Projects can be held up indefinitely for want of political will to free up the rail corridor or provide other approvals. Even where government guarantees exist, investors and lenders will want certainty the project is going to work rather than falling back on a guarantee that may be difficult to enforce in practice.

Many rail projects in Africa face two fundamental issues: firstly, a disconnected, extremely old and poorly maintained rail system, and, secondly, a number of gauges that do not facilitate an efficient commercial or metro rail service, most commonly Cape gauge (1067mm), as well as a large extent of 1.000m narrow gauge.

There seems to be general agreement that new projects should be based on standard gauge (1435mm). There are several instances throughout Africa where direct access to commodities or ports is hampered by the fact that, across the various regions through which the rail line proceeds, different gauges have been used.

Any project must therefore consider whether it is better to simply refurbish the narrow gauge line or to replace it with a standard gauge line to increase speed and capacity on the network. By way of example, Nigeria is taking the latter approach with the current upgrade of the line between the capital Abuja and Kaduna in the north-west of the country.

Standardisation of gauge will also assist intra-regional connectivity where similar projects are taking place in neighbouring countries, and intergovernmental agreements have already been signed among Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda to this effect.

The African railway system is not interconnected. While there may be some major arterial rail links, there is very little incentive to develop branch lines, as it is simply not economically practical to build or operate them. One overall strategy appears to be to develop a standard gauge North/South line, and to develop branch lines that would serve major metropolitan, industrial and natural resource nodes. As Africa has sought to introduce the concept of commodity beneficiation, raw materials are now more likely to move from a mine to a processing plant, and then on to a port for export, and this in turn is a driver for new rail infrastructure development (such as that proposed in the Zambian copper belt). In certain circumstances, specialised products need to be brought in to assist in the beneficiation process, which requires bespoke rail wagons and improved rail infrastructure. If these have not been built, purchased or developed, then the main rail initiative, focussing on the export of beneficiated material, may simply not be feasible.

There have been numerous transport surveys and strategies that have highlighted the lack of transport and logistics skills generally within Africa. This is of major concern to investors for whom the repair and maintenance of locomotives, rolling stock and rail infrastructure is pivotal to the financial sustainability of any project. Locomotives require very careful monitoring and maintenance schedules, as well as suitably equipped workshops to carry out this process. Consequently most rail projects will require that these facilities and related skills be provided.

A further issue relating to the maintenance of locomotives and rolling stock is the need for a sufficient pool of skilled labour and technical expertise. It is often necessary to ensure that there are proper plans in place to retain, recruit and/or adequately compensate skilled employees to avoid any delays, increased costs or projects being abandoned. Transport skill migration is a legitimate worry for rail operators. These skills are much sought after, but as a consequence of the inattention paid to rail infrastructure generally, little has been done to maintain a constant supply of employees with these skills.

In addition, an adequate and regular supply of diesel and electricity form a critical part of the operation of any rail system. However, the ability of the relevant utility provider to produce sufficient uninterrupted power can sometimes present a challenge.

Most investors will only be able to fully achieve their objectives if the economy in the country in which they have invested continues to improve, or at least avoids any material adverse decline. Investment into African infrastructure projects is regarded as high return, but also high risk. The recent (and hopefully short-term) decline in demand for Africa’s resources has seen a growth slowdown, which has not been helped by other socio-economic difficulties including foreign currency shortages, disease, civil unrest, unemployment, and shortages of skills, food, manufactured goods, fuel and electricity.

Most African infrastructure deals are contracted under local laws, which is usually mandatory when contracting with the state. In contrast many other contractual arrangements, such as for construction, supply of equipment and financing are often made subject to the laws of other jurisdictions on grounds of legal certainty or to reflect the provenance of the relevant services.

The international nature of the projects means that care must be taken to ensure that any dispute can be referred to suitable tribunals, and that any foreign award can be enforced in the jurisdictions of both the project assets and the project parties. It is also important to establish how the local judicial structure will respond to matters where urgent relief is required or where rights need to be enforced. It is always useful to have a good understanding of the efficacy of the court system, the costs involved in the legal process (in some jurisdictions court costs can be prohibitive), and the general ability of the courts to have judgements or orders enforced.

Where it is difficult to get substantial certainty investors may consider insuring against political risk, such as the risks of expropriation, restrictions on repatriation or exchange of funds or the general risk of a state entity defaulting on its obligations. In addition, the use of development banks to cofinance a project will give a measure of stability (given that the same institutions often hold the purse strings for bilateral loans). Furthermore, the project may be structured so as to use appropriate investment vehicles in order to benefit from bilateral investment treaties (BITs) which provide legal coverage for a range of political risks, and also may provide for ICSID-administered arbitration, which brings in the implicit support of the World Bank to ensure that judgments are satisfactory.

A carefully crafted force majeure clause is essential – it is most important that an investor is aware of local or territorial circumstances that may arise and which could prevent one or both parties from performing any contractual obligation. One method of spreading certain risks is to ensure that appropriate insurances are in place in respect of parties who may be unable to fulfil their obligations, or are in breach of the obligations they are supposed to fulfil. Investors must also consider what risks are uninsurable, or cannot be economically insured, and make appropriate arrangements in that regard.

Many contracts with state entities make a distinction between political and non-political force majeure; political force majeure being those events where the government has a greater degree of influence (expropriation, hostilities, national strikes, interference by government authorities), and therefore the government may be asked to give a greater degree of financial protection (for example, a “make whole” provision, or a right of termination with return of profit). This category also often includes protection against changes in law or the regulatory approach of government departments (especially where consents have additional conditions imposed) or this may be dealt with through stabilisation clauses. These provisions may be necessary in the absence of the other legal routes of protection referred to in the previous section.

Some African rail infrastructure projects have attracted funding by providing a sovereign guarantee that debt will be underwritten in the event of default, however this of itself does not always guarantee an exit route where the project is not delivering. For example, if the concessionaire defaults the government might choose not to exercise its right to terminate the project in which case that project may lie in limbo indefinitely, and the lenders may still have to find an alternative work-out solution or negotiate with the government for an early exit. To that extent, the sovereign guarantee is not always a panacea against project risk.

Like any developing investment environment, Africa is not without its challenges and obstacles. What is very clear is that a broad experience of different solutions for transport infrastructure projects, coupled with appropriate “in country” knowledge of how to overcome and avoid the challenges and obstacles that are specific to each market, will be vital to the success of any venture.

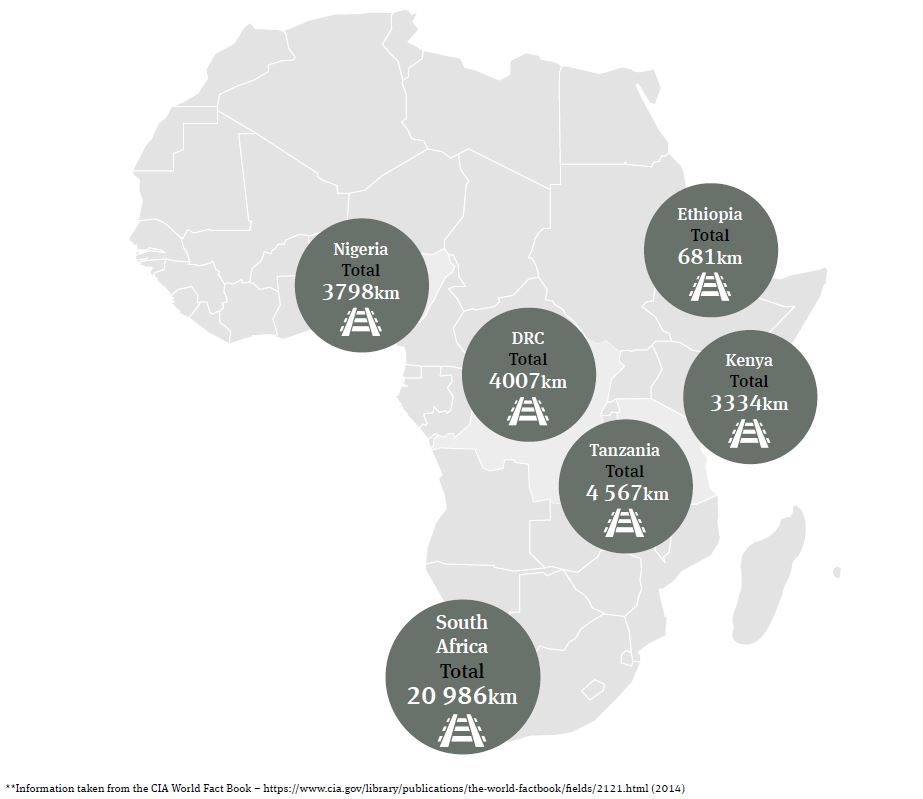

Rail network lengths in selected key African economies (km)

| Country | South Africa | Tanzania | DRC | Nigeria | Kenya | Ethipoia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 20 986 | 4 567 | 4 007 | 3 798 | 3 334 | 681 |

| Cape gauge (1067 mm) | 19 756 | 1 860 | 3 882 | 3 505 | — | — |

| Standard gauge (1435 mm) | 80 (electrified) | — | — | 293 | — | — |

| Other narrow gauge (1000 mm) | — | 2 707 | 125 | — | 3 334 | 681 |

| Of which electrified | 80 (standard) 8 271 (Cape) |

— | 858 (Cape) | — | — | — |

Publication

Ten things to know about insurance regulation in 19 countries.

Publication

A recent decision made by the UK's Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) brings into sharp relief the challenges for airlines to strike a balance between marketing their sustainability efforts in an understandable and compelling way, whilst avoiding criticism for “greenwashing”.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025