The corporate taxation of cross-border groups is at the brink of significant change. In 2021, after years of discussions, the members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework (IF) on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting agreed a blueprint to impose new taxing rights in respect of low-taxed income of large multi-national enterprises (MNEs). The OECD has since published model rules and commentary on a key aspect of this blueprint, known as the OECD Pillar Two GloBE Rules (the GloBE Rules), and various regions and jurisdictions are now moving quickly towards implementation in accordance with ambitious timelines.

The aim of the GloBE Rules is to ensure that MNEs pay a minimum level of corporate income tax in respect of each jurisdiction in which they have a presence through one or several group entities either being tax resident or having a permanent establishment there; simply put, they are designed to reduce the scope for tax rate arbitrage.

The GloBE Rules come into play where the primary taxing jurisdiction is not charging corporate income to tax at an effective rate of 15% or more; the idea underpinning the GloBE Rules is that this leaves taxing rights on the table and it will then be open to certain other jurisdictions to take up those taxing rights instead. This is a novel way of conceptualising and allocating international taxing rights. The implication of the GloBE Rules is therefore to create radically new taxing nexus rules.

Key concepts

The GloBE Rules will apply to international MNE groups (i.e. groups with one or more controlled entities or permanent establishments located in a jurisdiction other than the UPE jurisdiction) with annual global consolidated revenue of more than €750 million. MNEs are generally in scope if the revenue in the Consolidated Financial Statements in two of the four Fiscal Years immediately preceding the tested Fiscal Year exceeds this threshold.

Certain types of groups and entities will be excluded from the scope of the GloBE Rules (although their revenue still counts towards the €750 million test); this will be the case in respect of governmental entities, pension funds, some investment vehicles as well as international and non-profit organisations.

Broadly speaking, the GloBE Rules contain detailed provisions to (i) calculate whether an MNE is subject to additional tax (referred to in the GloBE Rules as Top-Up Tax); and (ii) allocate taxing rights in respect of any such additional Top-Up Tax.

Calculation of Top-Up Tax

The GloBE tax calculation is based on six key concepts:

- First, the “Income” of the MNE is calculated by reference to the net income or loss in its consolidated financial statement. The Income is calculated on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis and permanent establishments are to be considered separately for these purposes. While an MNE’s Income figure calculation for each jurisdiction is based on its accounts, the GloBE Rules provide that certain adjustments should be made to those figures in order to align Income figures to a common GloBE base calculation; this will entail adjustments for certain taxes and the exclusion of dividend receipts from the calculation. Some types of income, such as international shipping income, will be excluded altogether.

- Second, the “Adjusted Covered Taxes” of the MNE is calculated by reference to the current tax expense accrued for the Income. Again, this is done at jurisdictional level by reference to the Income in that same jurisdiction, using the financial accounts as a starting point. This figure is then subject to adjustments, including for capital gains, tax credits, prior year losses and adjustments to account for temporary differences between tax and accounting positions (including in respect of capital allowances). The calculation also includes a mechanism for re-allocated tax that is properly chargeable to other group entities, including withholding tax and controlled foreign companies (CFC) charges.

- Third, the MNE’s “Effective Tax Rate” in a given jurisdiction is calculated by dividing the Adjusted Covered Taxes amount by the Income amount. If this Effective Tax Rate figure is 15% or more, that means that no Top-Up Tax additional tax charge will arise to the MNE pursuant to the GloBE Rules in respect of that particular jurisdiction, and the following steps can be disregarded. If, however, the Effective Tax Rate figure for any jurisdiction is less than 15%, this means that additional tax will be due to the MNE in respect of that jurisdiction and so the next three steps must also be calculated.

- Fourth, the “Top-Up Tax Percentage” for a given jurisdiction is calculated by subtracting the Effective Tax Rate percentage from 15%.

- Fifth, the “Excess Profit”, being the amount chargeable to tax pursuant to the GloBE Rules in respect of a given jurisdiction, is calculated by reference to the Income calculated at step 1 above, after making a deduction for a substance-based exclusion (calculated as a percentage of payroll costs and tangible assets). This percentage will be at least 5% (initially 10% for payroll and 8% for tangible assets in 2023). In effect, the carve-out operates to exclude profits that are not typically associated with base erosion.

- Finally, the “Top-Up Tax” is calculated by multiplying the Top-Up Tax Percentage with the Excess Profit amount. If any domestic minimum tax (chargeable by reference to the GloBE Rules) is charged on the MNE in that given jurisdiction, this will operate to reduce the amount of the Top-Up Tax. In addition, the GloBE Rules provide for an elective de minimis exclusion where an MNE has revenues of less than €10 million and profits of less than €1 million in a jurisdiction. The effect of making the election is that the Top-Up Tax for that jurisdiction is deemed to be zero.

Allocation of taxing rights

The GloBE Rules contain two mechanisms for charging any Top-Up Tax that may be due in respect of an MNE in a particular jurisdiction:

- First, the income inclusion rule (IIR), will allocate full (or partial) taxing rights to the jurisdiction in which the MNE’s ultimate parent (UPE) is located. If this jurisdiction has not implemented the IIR, taxing rights may fall to an intermediate parent entity’s jurisdiction instead. The amount of tax that can be charged pursuant to the IIR is uncapped;

- Second, in the alternative, the undertaxed payments rule or “UTPR” will allocate a proportionate share of taxing rights to any jurisdiction in which a member of the MNE is based. Where the IIR is effectively an additional tax amount charged on a parent entity by reference to its subsidiaries, it is expected that the UTPR will primarily be implemented to operate so as to deny deductions that would otherwise have been available. As such, the UTPR may not have any effect at all where there are no relevant deductions available to be denied.

The IIR is subject to a split-ownership rule for shareholdings below 80%. In cases of split ownership further down a chain, such partially-owned entities will be subject to the IIR in priority to the UPE, thereby ensuring that third parties bear a fair share of any Top-Up Tax. The amount of Top-Up Tax charged on entities higher up the chain will be reduced accordingly.

There is a clear hierarchy between the two charging mechanisms: the UTPR will only come into play where the IIR has not operated to exhaust taxing rights pursuant to the GloBE Rules. This will generally be the case where parent entities are based in jurisdictions that have not implemented an IIR (including where low-taxed entities are not wholly owned and only some of the parent entities are subject to an IIR).

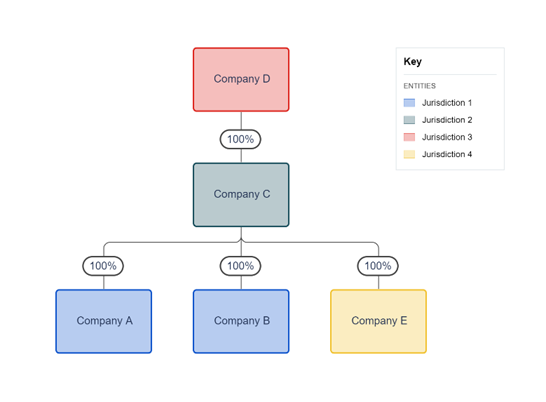

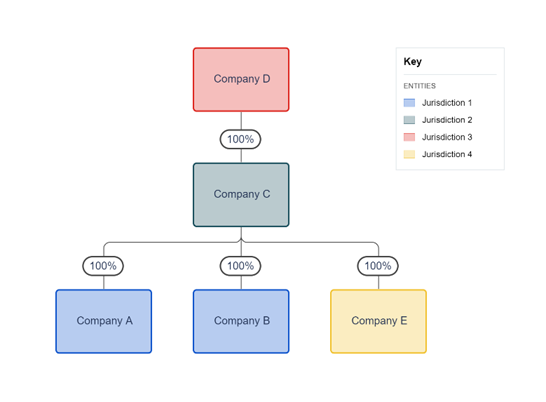

The following example illustrates how the IIR and UTPR operate:

Company A and Company B are resident in Jurisdiction 1 and are wholly owned by Company C which is resident in Jurisdiction 2. Company C in turn is wholly owned by Company D which is resident in Jurisdiction 3. Companies A, B, C and D together form part of an in-scope MNE of which Company D is the ultimate parent.

Assuming that the Effective Tax Rate of Companies A and B in Jurisdiction 1 is less than 15%, the starting point under the GloBE Rules is that if Jurisdiction 3 has implemented an IIR, the Top-Up Tax in respect of Companies A and B will be imposed by Jurisdiction 3 on Company D. If Jurisdiction 3 has not implemented an IIR but Jurisdiction 2 has, then Jurisdiction 2 can charge the Top-Up Tax on Company C.

If neither Jurisdiction 3 nor Jurisdiction 2 have implemented an IIR, then the UTPR will come into play so that any jurisdiction in which the MNE has a presence (including, for example, through Company E, being another subsidiary of Company C, resident in Jurisdiction 4) can charge a proportionate amount of the Top-Up Tax by denying a tax deduction or making an equivalent adjustment in respect of the MNE entity based in its jurisdiction.

Points of interest

Exactly how the rules apply will of course depend on the specific MNE group but there are some specific points which merit particular mention:

- MNEs in the initial phase of their international activity will be exempt from the UTPR; this applies where its group has a maximum of € 50 million of tangible assets abroad and operates in no more than five other jurisdictions. This UTPR exclusion applies for five years after the MNE comes within scope of the GloBE Rules for the first time.

- The GloBE Rules contain certain transitional rules that specifically affect assets being transferred intragroup after 30 November 2021. This could be a key concern in cases where an asset, e.g. IP, is transferred during this transitional period within the MNE. In such cases, the rules provide that the transferred asset must be recorded at its historic book value for GloBE purposes, while for local tax purposes the transfer would still take place on arm's length terms (i.e. at fair market value). As a result of this difference, the GloBE Income for the transferee would be higher than the local taxable profit (which does take into account the depreciation over the hidden reserve), resulting in a (potentially substantially) lower Effective Tax Rate. This is regardless of any taxation of the hidden reserve at the level of the transferor. The result could be that the transferee jurisdiction's Effective Tax Rate is below the 15% threshold; as such, it is an important point to consider for MNEs in those circumstances.

- We know that there are several jurisdictions where the statutory tax rate is below 15% or where the Effective Tax Rate may in certain cases be below 15%. MNEs active in such jurisdictions may suffer Top-Up Tax (which could be levied in the UPE jurisdiction under IIR or other IF participating jurisdictions under UTPR). Examples of such jurisdictions are Switzerland, Hong Kong and the United Arab Emirates. There is a trend that these jurisdictions are introducing a Qualified Domestic Tax-up Tax (QDTT) of their own, meaning that the amounts that would otherwise constitute a Top-Up Tax are instead levied and collected in the low-tax jurisdictions themselves. On the basis that the liabilities under these local taxes are correctly included as Adjusted Covered Taxes, this should not result in double taxation but the compliance of these local taxes with the QDTT regime should be carefully considered.

- Even if the group operations are in tax-paying jurisdictions, groups are likely to have a significant additional compliance cost in confirming that there is no pick up, as this requires the specific GloBE calculation to be made.. Complications may arise if in the particular jurisdiction there are tax credits or operating losses. It is already clear that this will not be a straight-forward process, even if the details of the rules are not yet fully known.

Next steps

The publication of the GloBE Rules and the Commentary by the OECD marks a milestone towards implementation of the new framework; yet, much remains to be seen about how they will operate in practice. In addition, a number of key points relating to the operation of the GloBE Rules are yet to be agreed at international level. This includes the nature and scope of safe harbour provisions to allow for simplified application of the rules in low-risk situations.

While the GloBE Rules are subject to a “common approach”, meaning that they should be implemented and administered by IF members in a way that is consistent with the outcomes provided for under Pillar Two, there will nevertheless be scope for divergence as to how jurisdictions choose to approach certain points. In particular, the GloBE Rules leave open to IF members to impose a “domestic minimum tax” on low-taxed MNEs – the QDTT discussed above – so as to pre-empt other jurisdictions from charging that tax pursuant to an IIR or UTPR. Some jurisdictions (including the UK and Canada) have already signalled that they will likely impose a domestic minimum tax in this way.

In addition, the OECD is to look at the conditions under which the US GILTI regime will co-exist with the GloBE Rules, to ensure a level playing field. There are a number of differences between the Pillar Two regime and the existing US GILTI regime, including with regard to minimum tax rates, minimum thresholds, exclusions and ownership conditions.

The OECD’s intention is that the GloBE Rules should be enacted at national level in 2022, with the IIR to come into effect in 2023 and the UTPR to follow in 2024. Given the complexity of technical aspects not wholly addressed by the GloBE Rules and concerns raised by the business community, it may prove difficult for IF members to meet those timelines.