Publication

Distress signals: Cooperation agreements or mergers to the rescue in times of crisis?

The current volatile and unpredictable economic climate creates challenges for businesses.

Global | Publication | July 2021

Supply chains operate in an environment shaped by trade issues (such as sanctions, export controls, and tariffs), where national security is an increasingly important consideration. International sanctions regimes are complex and often respond to volatile political landscapes. Businesses will need to navigate the often complex issues involved against a background of changing governmental trade and industrial policy.

The new reality of cooperation between international regulators in different jurisdictions requires businesses to adopt a coordinated, global approach for their supply chains in relation to such matters.

Failure to comply with sanctions regimes in one jurisdiction can result in the imposition of significant civil and criminal sanctions, including draconian fines and even imprisonment for individuals. Not adhering to national security laws that control foreign direct investment can bring an abrupt (and costly) end to new or proposed transactions. Similarly, business and commercial imperatives can be quickly put at risk where a business’s supply chain strategy is not informed by then current governmental trade and industrial policy.

In this briefing, using the US and the UK as our primary case studies (with insights from other jurisdictions, such as the European Union (EU), where appropriate), we consider the following in relation to their impact on global supply chains:

On February 24, 2021, President Biden signed an executive order on “America’s Supply Chains” which began a 100 day review process for evaluating the strength of the supply chains for four key industries, with a focus on several specified products, as well as a separate, year-long review for other sectors. The assessment is meant, in part, to address the “exclusive or dominant supply of critical goods and materials” by countries that are, or are likely to become, “unfriendly or unstable.”

The four sectors prioritized during the first 100 days included:

The year-long reviews include supply chains of the following industries: defense, public health and biological preparedness, critical sectors and subsectors in information and communication technology, energy, transportation, and agricultural commodities and food products.

The new order also states that the government will solicit input from outside stakeholders, including from the various industries falling within the scope of the order, but it is not yet clear what form this input will take. Moreover, it remains unclear what types of remedies will result from these reviews and how they will impact the various players in each of these industries. However, it is unlikely that such remedies will require US companies to cease their overseas operations altogether.

The new executive order does not supplant the former administration’s executive order on the supply chains for information and communications technology and services (ICTS). Indeed, on March 22, 2021, the US Department of Commerce proceeded with implementing a new interim final rule that creates processes and procedures for reviewing certain transactions involving ICTS – specifically, ICTS that has been designed, developed, manufactured, or supplied, by parties owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of, a “foreign adversary.”

The list of foreign adversaries currently includes China (including Hong Kong), Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Russia, and Venezuela’s Maduro regime.

| Products Undergoing Priority Review | Industries Undergoing Year-long Review | Countries Subject to New Restrictions for ICTS Transactions | ||

|

|

|

||

| Source: US Supply Chain Reviews |

Between September 2019 and November 2020, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) issued a series of ten “Withhold Release Orders” (WROs) on certain goods produced by specific companies in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), including garments, hair products, and computer parts. Then, in January 2021, only days before the change in administrations, CBP issued a comprehensive, far-reaching WRO on all cotton and tomato products originating from the region, which included downstream products such as apparel, textiles, and tomato sauce. Most recently, in June 2021, CBP issued another WRO on silica-based products manufactured by Hoshine Silicon Industry Co. Ltd. (“Hoshine”), a company located in Xinjiang, and its subsidiaries. Altogether, three of the six WROs issued by CBP in its 2021 fiscal year so far, as well as eight of the 13 issued in its 2020 fiscal year, have been on goods made by forced labor in China.

These orders prevent such merchandise from entering the United States when information “reasonably but not conclusively” indicates that the goods were produced using forced labor. Importers that wish to import these goods must provide a certificate of origin and a supply chain audit report, which can be quite burdensome.

In February, CBP provided further guidance on the supporting documentation that was required. President Biden’s 2021 trade agenda, which was released on March 1, 2021, continues to put forced labor front and center. Accordingly, the administration will likely continue to issue WROs on goods from the XUAR, which may be targeted or wide-ranging. However, CBP has also indicated that it will take a measured approach to enforcing the bans that were issued under the previous administration.

The most recent WRO was issued in concert with other actions targeting solar product manufacturers in Xinjiang. First, the US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security’s (BIS) added five entities, including Hoshine, to the “Entity List,” which prohibits, absent a license, the export, re-export, or transfer (in-country) of any items subject to the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) to these entities. According to the Commerce Department, 53 of these entities have been “implicated in human rights abuses of ethnic minorities from Xinjiang” and 15 have been implicated in abuses related to forced labor, specifically.

Further, the US Department of Labor updated its “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor” to include polysilicon produced with forced labor in China. The most recent edition of the list contains other products from China that have links to forced labor in Xinjiang or by Uyghur workers transferred to other parts of China, including cotton, garments, footwear, electronics, gloves, hair products, textiles, thread/yarn and tomato products.

Additionally, both houses of the US Congress are, as of the date of publication, considering a bipartisan bill, the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which would prohibit the importation of goods made with forced labor in China. The legislation, which is an updated version of a bill that passed nearly unanimously in the House in 2020, would create a “rebuttable presumption” that any goods made in the XUAR are made with forced labor and are prohibited from entering the United States unless an importer can show “clear and convincing evidence” to the contrary.

The bill also, among other provisions, would:

| Withhold Release Orders |

|

| Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act |

|

| Source: US Policies and Legislation Targeting Forced Labor in China |

What should businesses be doing now?

In light of these regulatory and legislative trends, along with coordinated actions in Canada and the United Kingdom, businesses should assess their entire supply chains and consider moving their procurement and operations away from the XUAR, or else they will likely be required to enhance their policies and procedures for tracing and documenting their goods to ensure that their supply chains do not rely on forced labor.

For more information, see our publication Around the Globe: Business Human Rights Update

Overall, global trade declined by about 9% in 2020. This trend was punctuated by a fourth quarter uptick in trade in goods, driven in large part by manufacturing in East Asia, while trade in services remains depressed.

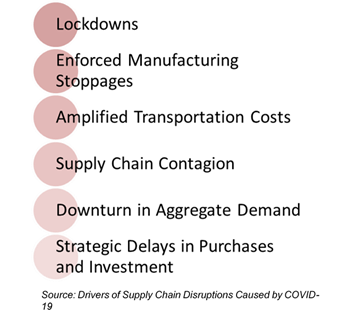

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global trade was considerably greater than the impact of other recent pandemics, and was driven by a multitude of factors, including:

Such disruptions to supply chains have underscored the weaknesses of traditional, analog trade transactions, and have further demonstrated the potential benefits of trade digitalization.

Specifically, the advent of distributed ledger technology (DLT) has the potential to help improve transparency and efficiency in global supply chains. Meanwhile, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala of Nigeria took office as the seventh Director-General of the World Trade Organization (WTO) on March 1, 2021, which may be the harbinger of WTO reform on the horizon.

As of the date of publication, the Biden administration has not reversed any of the policies of the previous administration that led to its trade war with China. President Biden has indicated that he does not intend to eliminate the existing tariffs without first reviewing the Phase One Trade Deal of early 2020 and consulting with US allies to form a “coherent strategy”.

Meanwhile, China’s foreign minister has called on Biden to remove the tariffs on Chinese goods that were imposed by the previous administration. The tariffs were among the issues raised in advance of the high-level US–China talks that took place in March 2021, but no trade-related policy changes have yet to emerge from those meetings.

Foreign direct investment regimes (FDI), such as the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), will likely have some role to play in addressing the supply chain vulnerabilities brought to light by the COVID-19 pandemic.

CFIUS will likely apply heightened scrutiny to transactions that implicate products for which there have been acute shortages during the pandemic, including in particular personal protective equipment (PPE).

Further, CFIUS may ultimately be used to address vulnerabilities unearthed by the Biden administration’s supply chain reviews, discussed above, although it is likely to stay focused on its purview of national security to address issues that arise with transactions involving critical goods and materials and critical minerals.

In 2019, the EU adopted Regulation 2019/452 (FDI Regulation), which creates a new framework for screening foreign direct investments into the EU. The FDI Regulation creates a new cooperation mechanism in which Member States, and the European Commission (EC) itself, may issue comments and opinions on transactions involving FDI in another Member State’s territory, and the Member State in question must give those comments and opinions “due consideration.” In the case of investments deemed to be of “Union interest,” the EC will have greater authority, as Member States in which an FDI is planned will have to take “utmost account” of EC opinions and explain any non-compliance.

The FDI Regulation represented a bold step, inserting the EC into a hitherto jealously guarded area of Member State authority. The FDI Regulation has applied since October 2020. For more information, see European Union: COVID-19 crisis inspires global tightening of Foreign Investment Screening.

A new FDI regime has recently been enacted in the United Kingdom, the National Investment and Security Act 2021 (NSI Act). It reflects a global trend for more intervention in and scrutiny of national security issues (as demonstrated by the new EU FDI Regulation). The United Kingdom Government intends for the NSI Act to strengthen the UK’s ability to intervene in transactions to protect UK national security while also ensuring a proportionate and efficient approach to screening. The NSI Act replaced the Secretary of State's ability to scrutinize transactions which give rise to a national security consideration under the Enterprise Act 2002.

Headline points to note about the new legislation are:

For more information, see The UK’s new NSI regime: What do you need to know?

In this section, using EU/UK trade relations as a case study, we look at how supply chains can be impacted by legal and constitutional changes in the relationship between trading nations.

Following the end of the Brexit transition period at 23:00 on December 31, 2020, the UK-EU Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) is now in effect. The UK’s decision to leave the EU presents opportunities and challenges. The TCA now governs the relationship between the EU and consists of an FTA, a partnership for citizens’ security and a horizontal agreement on governance.

Beyond trade in goods and services, the TCA also covers a broad range of areas, such as investment, competition, state aid, tax transparency, air and road transport, energy and sustainability, data protection, and social security coordination. In terms of supply chains, the issues divide into technical as well as wider trade policy issues.

In terms of the technical issues, businesses operating supply chains across the UK/EU are having to address a range of matters – for example, contractual and counter-party risk and tax issues will affect many supply chains, as will changes in relation to the intellectual property rights regime. The full range of technical issues, and how they affect particular industries, can be found here: Beyond Brexit: Navigating the new landscape.

The TCA provides for a free trade area without customs duties, export duties, taxes or other monetary charges on goods moving between the EU and the UK that comply with the rules of origin criteria stated in the TCA. Quantitative restrictions, such as quota limits on the volume of imports or exports between the UK and EU, will also be prohibited under the TCA.

Goods must meet the relevant rules of origin to qualify for zero tariff and zero quota trade. The TCA contains a separate chapter defining “originating goods”, and provides for full bilateral cumulation of both materials and processing, which allows EU inputs and processing to be counted as UK input in UK products exported to the EU and vice versa. In addition, the TCA includes facilitations on average pricing, accounting segregation for a number of products and materials, and tolerance by value.

The TCA includes a chapter on technical barriers to trade (TBT), with provisions on preventing, identifying and eliminating unnecessary measures that present TBT. This allows each party the freedom to regulate goods in the way most appropriate for their market, but provides for cooperation on areas such as technical regulation, conformity assessment, standardization, accreditation, market surveillance and marking and labelling.

With regard to technical regulation, each party is required to carry out impact assessments of planned technical regulations and assess the available regulatory and non-regulatory alternatives that may fulfil the party’s legitimate objectives. Relevant international standards are to be used as the basis for such technical regulations except where these would be ineffective or inappropriate in the particular circumstances.

The TCA establishes new customs checks and procedures for goods traded between the UK and the EU, now that the UK has left the EU Customs Union. The chapter on customs and trade facilitation (CTF) includes measures to facilitate legitimate trade by addressing administrative barriers for traders, such as through mutual recognition of Authorized Economic Operators (AEO) (or “trusted trader”) schemes, with provisions to support the efficiency of documentary clearance, transparency, advance rulings and non-discrimination.

The TCA includes provisions on the treatment and level of access for service suppliers and investors between the EU and UK, securing market access across a broad range of sectors, including professional and business services, financial services and transport services. Certain sectors are, however, excluded from the scope of the TCA, such as certain air services as well as audio-visual services. The TCA’s approach to services and investment is aligned to the EU’s FTAs with other countries, such as the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement.

The TCA includes standard provisions on services and investment found in other FTAs. These include provisions on:

The TCA also includes a separate provision on local presence, to ensure that cross-border trade is not inhibited by establishment requirements, although the market access provisions may be interpreted as prohibiting requirements on local presence in any case.

The TCA expressly re-states the commitment of the UK and each of the EU Member States to ensuring that individuals have a right to protection of personal data and privacy, and sets out principles that are consistent with the General Data Protection Regulation 2016 (the GDPR).

The GDPR allows personal data to be shared freely between EEA Member States and countries that are subject to an “adequacy decision,” which is essentially a determination by the European Commission that a jurisdiction has data protection laws that are substantively equivalent to those of the EU. In the absence of such an adequacy decision, additional safeguards are required to be put in place prior to transferring personal data from the EEA to a non-EEA jurisdiction (i.e. a third country).

On June 28, 2021 the European Commission published a positive adequacy finding in respect of the UK’s data protection regime (the Decision). This means that personal data can continue to flow freely from the EU to the UK without the need for organizations to take further measures.

For the time-being, however, the Decision does not concern personal data transferred for United Kingdom immigration control purposes or which otherwise falls within the scope of the exemption from certain data subject rights for purposes of the maintenance of effective immigration control.

The Decision will apply for an initial period of four years. It may be extended by another four years if the European Commission’s monitoring of the Decision reveals that the UK still maintains adequate protection for personal data. However, if the European Commission thinks that the UK no longer maintains adequate protections and the UK authorities fail, within a specific timeframe, to take appropriate corrective actions, the European Commission may partially or completely suspend or repeal the Decision.

For more information, see EU – UK data transfers can continue: UK receives much welcome adequacy decision.

The TCA seeks to ensure that the UK and EU will cooperate on digital trade issues and includes a digital trade chapter which sets out the terms under which businesses can provide products and services to each other via digital channels, such as over the internet. No customs duties will be imposed on electronic transmissions, and there is a positive obligation for the UK and EU to cooperate on the development of emerging technologies.

Equal treatment is given to electronic signatures and electronic documents against paper documents, and services can be provided digitally by default without requiring any prior authorization. There are a few exceptions to this, notably, legal services, gambling services and broadcasting services.

The TCA also creates a framework for UK-EU cooperation in the field of cybersecurity. As well as the UK’s participation in expert bodies, such as European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) and the Network and Information Systems (NIS) Cooperation Group, the UK and EU will cooperate in the field of cyber issues by sharing best practices and cooperative practical actions aimed at promoting and protecting an open, free, stable, peaceful and secure cyberspace.

The UK and EU agree not to require the transfer of, or access to, the software source code of the other’s residents or businesses. This is without limit to private parties’ ability to negotiate agreements for the transfer of source code.

The UK and EU agree to adopt or maintain measures to ensure the effective protection of consumers engaging in e-commerce transactions - for example, by requiring suppliers of goods and services to act in good faith and to abide by fair commercial practices. The parties also recognize that consumer protection bodies can cooperate and enforce breaches of UK and EU consumer rights in order to protect consumers and enhance online consumer trust.

The TCA contains a provision on open government data – it provides that, when governments choose to make non-personal or anonymized public sector data available, the data will be (among other things) easily accessible, in machine-readable format, and regularly updated.

Under the TCA both parties agree to cooperate on regulatory issues with regard to digital trade:

The TCA will restrict the current cross-border road transport system to a limited extent. While EU and UK road haulage operators can continue to move goods between and through each other’s territories, limits are imposed on the number of additional movements a road haulier can make in the other’s territory. From January 1, 2021, EU road hauliers can conduct up to two cabotage operations in the UK, and UK hauliers can either conduct two cross-border operations or one cross-border and one cabotage operation.

With regard to aviation, the TCA provides EU and UK carriers with unlimited rights to fly between the UK and the EU. The UK can negotiate with individual EU member states for the provision of the right for UK carriers to operate to an EU member state and then to travel to a non-EU country and vice versa for cargo services only.

Air transport services are subject to the general “level playing field” provisions regarding social and environmental issues, but there are some specific provisions relating to non-discrimination in the provision of ground handling services, allocation of slots and the taxation of aircraft fuel.

On shipping, the TCA guarantees the EU and the UK open and reciprocal access to maritime services, including the use of port infrastructure and services (such as pilots, berthing and loading/unloading facilities), access to, and the use of, maritime storage and warehousing and provisions. The TCA also allows UK shipping companies to move empty containers and provide feeder services between ports in an EU member state, subject to authorization.

The issue of maritime cabotage, the sea transport of passengers and goods between two sea ports in the same country by an operator from another country, is excluded from the ambit of the TCA, which means that there will be no reciprocity between the EU and the UK in this area.

In line with the level playing field commitments, the EU and UK have agreed not to weaken tax legislation below OECD standards. This includes the exchange of information regarding financial accounts (i.e. Common Reporting Standards or Automatic Exchange of Information), tax rulings, cross-border tax planning and Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) corporate interest restriction, hybrid mismatch and Controlled Foreign Companies (CFC) rules and public country-by-country reporting rules relating to large financial institutions. These rules are contained in a Joint Political Declaration on Countering Harmful Tax Regime.

The TCA does not include provisions constraining domestic tax regimes or tax rates.

The TCA covers the “level playing field for open and fair competition and sustainable development” under Title XI. This section of the TCA sets out general principles, and then further detail with regard to competition policy and subsidy control (i.e. provisions to manage the UK’s exit from the current EU State aid regime).

The general principles are unsurprising – commitments to:

A Trade Specialized Committee will be established to oversee operations of the TCA in this respect.

In this section, using the UK as a case study, we look at how significant change in governmental trade and industrial policy can impact upon supply chains.

The UK Government’s espoused aim is to secure FTAs covering 80% of UK trade within the next three years. The UK Department for International Trade (DIT) has negotiated and concluded FTAs with countries including Japan, Canada and Australia, and is prioritizing trade negotiations with the USA and New Zealand as well as the UK’s accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The UK Government considers the Coronavirus pandemic to have demonstrated the importance of keeping trade flowing and of building diverse supply chains that are robust in a crisis. To secure the UK’s future prosperity, the UK Government is aiming to adapt and trade more with all parts of the world to ensure the UK is not too reliant on any one region. A central feature of the UK Government’s approach has been to uphold the UK’s environmental, labor, food safety and animal welfare standards, while ensuring that FTAs provide tangible benefits for UK consumers, producers and companies.

The UK Government’s:

The UK Government’s policy on:

With regard to the protection of public services, the UK Government has pledged to protect the National Health Service (NHS) and maintain national security under prospective FTAs. As such, the UK Government’s policy is to maintain the position under the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA) by ensuring that FTAs do not apply to the procurement of clinical healthcare services, nor to goods and services indispensable for national security or defense purposes.

The UK Government’s aim is to secure “cutting-edge” provisions that maximize opportunities for digital trade across all sectors of the economy, while also promoting a world leading eco-system for digital trade that supports businesses of all sizes across the UK.

The UK’s approach also aims to include provisions in FTAs that facilitate the free flow of data, while ensuring that the UK’s high standards of personal data protection are maintained and preventing unjustified data localization requirements. As part of its trade policy, the UK Government is aiming to “future proof” all FTAs with digital provisions in order to take advantage of the benefits of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and increased digitalization.

Publication

The current volatile and unpredictable economic climate creates challenges for businesses.

Publication

Recent tariffs and other trade measures have transformed the international trade landscape, impacting almost every sector, region and business worldwide.

Publication

In mid-March 2025, Cognia Law and Norton Rose Fulbright’s Legal Operations Consulting team co-hosted a second roundtable event that brought together senior leaders, including GCs, COO and head of legal operations, from across the legal industry to discuss how to drive meaningful change within the legal ecosystem.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025