Publication

Supplementary reforms to the hydrocarbons sector

This Mexico decree issuing the LSH Regulations was published earlier this year.

Global | Publication | October 2016

Central America is rich in renewable energy resources and there exists tremendous opportunity to harness this potential. The region has a total installed generation capacity of 12GW. Guatemala and Costa Rica have the largest capacity, with approximately 3GW each, followed by Honduras and Panama, with just over 2GW each, and El Salvador and Nicaragua, with 1GW each. As a whole, Central American countries generated 43TWh in 2011.

Historically, Central America has been powered mostly by hydropower, but in the mid-1990s hydro’s share dropped as it began to be replaced by fossil fuels. In the mid-2000s, increasing shares of renewables, such as wind in Costa Rica, Honduras, and Nicaragua, decreased the region’s dependence on oil. Encouragingly, despite the range of fossil fuel options now available, the region is continuing to expand its use of renewable energy, a trend that is in the global interest as well as the economic, social, and environmental interest of Central American countries.

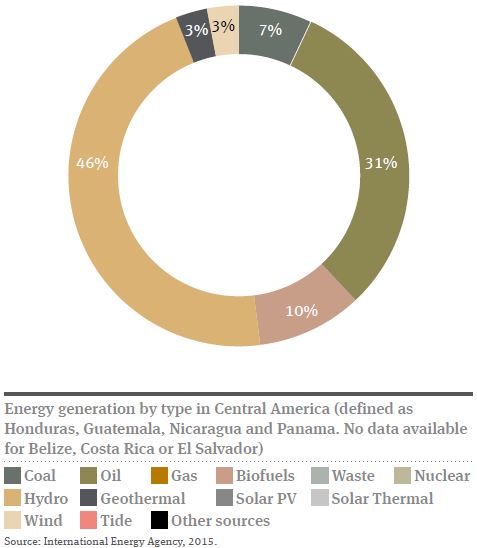

Today, the electricity matrix of the Central American region is divided mostly between hydropower (30 per cent large hydro, plus 12 per cent small hydro) and oil and diesel (38 per cent). However, concerns about dependence on oil, the environment and energy security have forced the region to develop other renewable resources.

Central America has the largest share of renewables (56 per cent) and the most diverse mixture of renewable generation, composed of biomass, geothermal, wind, and hydro. Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua have developed some geothermal resources. Costa Rica, Honduras, and Nicaragua have about 350MW in wind farms, and Panama has 158MW of wind energy in the pipeline.

The falling prices of renewables, their abundance in the region, and fit with a hydro-dependent electricity matrix indicates that the development of renewable energy is an attractive option for meeting growing regional energy demand and for providing energy security at a competitive cost.

Moreover, the declining costs of wind and solar equipment have made those technologies cost competitive in several markets in the region; this is especially true of those countries which depend on imported fossil fuels for power or have high electricity tariffs, like Nicaragua and Honduras.

In view of the increasingly favourable policies, incentives, and political support that have been introduced in the last five years, Central America has the potential to meet 100 per cent of its electricity needs with renewable energy.

The region’s estimated geothermal power potential is more than 20 times the current installed capacity, and geothermal power alone could satisfy nearly twice the region’s predicted electricity demand through 2020.

Existing regional wind power installations currently use less than one per cent of the available resource potential, even according to conservative estimates, and most Central American countries boast two to three times the annual solar radiation of world solar energy leaders such as Germany and Italy.

Most of the geothermal potential in Central America has not been exploited. Studies vary widely in estimates of regional geothermal resources and range from 2,700–13,000MW across about 50 different sites.

In Central America, wind has been harnessed to produce energy at utility scale. The total installed capacity of wind power in the region reached 298MW in 2011 and slightly more than 38 per cent of the wind power capacity was installed in 2010 alone. In 2011 Central America produced 738GW/h of electricity from wind, representing 1.7 per cent of generation in the region.

However, these trends do not reflect the entire region. Only three Central American countries (Costa Rica, Honduras and Nicaragua) currently have large-scale wind farms.

The regional interest in wind energy is expanding rapidly. The three countries mentioned above are currently installing and operating new plants. Panama, an ambitious newcomer, has licensed more than 950MW of wind capacity, which amount to a staggering 39 per cent of the installed generation capacity in 2012.

Solar energy in the region is in early stages, especially when it comes to market development. The first mid-scale photovoltaic power plant (by regional standards) is in Costa Rica, which has a 1MW plant that began operations in November 2012. In turn, a solar power plant of 1.2MW was installed in Nicaragua in February 2013. Each facility will produce enough energy to provide electricity to over 1,000 households.

Central American governments are aware of the importance of renewable energy as a means to reduce their dependence on large hydropower and imported fossil fuels, as well as to meet the region’s growing energy demand and provide energy access to currently underserved communities.

Countries in the region have issued ambitious policy statements that show a political will for the further advancement of renewables. There are a variety of regulatory measures in place to ensure that renewable energy continues to grow. For example, five of the seven Central American countries have established tendering procedures and three have adopted clean energy policies.

All countries except Nicaragua have adopted a biofuel mandate and Guatemala and Nicaragua have begun to experiment with feed-in tariffs. Most countries in the region have concrete policy mechanisms in place for advancing renewables. Tax incentives (to reduce costs, stimulate investment and increase the competitive advantage of renewable energy sources) are the most common, but the region also has positive experience in tendering for renewable energy projects.

Newer mechanisms, such as net metering, feed-in tariffs1, and renewable energy production laws are just getting off the ground in Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Panama.

The structure of Central American energy institutions has changed dramatically since reforms in the 1990s created new independent regulatory agencies, unbundled and privatised large state-owned utilities, and established competitive electricity markets in most countries (with the exception of Costa Rica and Honduras). Although new agencies initially faced obstacles connected with their lack of maturity, countries have developed stronger, more independent institutions over the years.

The Central American Electrical Interconnection System (SIEPAC) is the regional grid system, with 1,800 kilometres of transmission lines that connect 35 million electricity consumers from Guatemala to Panama.

The current SIEPAC phase cost an estimated US$494 million, and a second stage of development, which will require up to US$157 million in investment, is expected to double the system’s overall capacity from 300MW to 600MW. Official estimates are for the expansion to be completed by the end of 2015, although most experts in the region say that this timeline is unlikely.

Central America’s Regional Electricity Market (MER) was established as a supranational electricity trade regulator with its own set of rules for regional power transactions over SIEPAC lines.

Current efforts to strengthen electricity integration in Central America through SIEPAC and to streamline regional electricity regulation through the MER can benefit from international best practices for scaling up renewable energy through regional interconnection.

The region’s dependence on hydropower has led to concerns about energy security, especially given recent, extremely dry weather that has resulted in electricity shortages. In response, the Central American countries commissioned the creation of a regional grid (SIEPAC) that would enable international power exchanges. They also established a regional electricity market and a regulatory commission. To reinforce this interconnection and to enable access to North American and South American markets, a Mexico-Guatemala interconnection was completed and a Colombia-Panama interconnection is under construction.

The biggest challenge facing SIEPAC has been the creation of a regulatory framework for trade, given the region’s different power market structures. Central America experienced a wave of market liberalisation reforms in the 1990s, during which El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Panama liberalised their entire electricity markets, unbundled their vertically integrated utilities, and opened areas of generation, transmission, and distribution to private competition. Honduras and Costa Rica preserved their vertically integrated utilities, which are state-owned and operate as a single buyer. In both countries, additional generation is purchased from Independent Power Producers (IPPs).

Infrastructure challenges can present major concerns for developing any energy project in Central America, renewable or otherwise. Whether these challenges are perceived or real, they are often cited as particularly concerning for renewable energy deployment, increasing the risks and costs associated with renewable investments and, in extreme cases, preventing a prospective project from being developed. The distribution of renewables often means that existing grid networks must be extended to account for new factors, such as suitable project siting in resource-rich zones, and the need to manage intermittent generation.

The investment climate for renewables is influenced heavily by a country’s overall financial reality. Across the region, the capacity of countries to finance new projects with local and international funds varies widely. Panama, for example, has both a very healthy internal savings rate and a high level of foreign direct investment (FDI), whereas El Salvador has the weakest performance in both areas. This is consistent with the performance of investments in the power sectors of these countries. Nicaragua has negative internal savings, but a very high rate of FDI, while Guatemala and Honduras have modest but positive rates in both areas.

The major obstacle to integrating sustainability policies into the operations of financial institutions remains the lack of understanding of the risks and opportunities of renewable energy and a failure to address these with the right financial products.

Having said that, the ability and willingness of commercial banks to fund renewable energy projects has increased significantly in recent years. The Central American Bank for Economic Integration (BCIE) and BAC-San José (a private bank) signed a technical cooperation agreement within the framework of BCIE’s Green Initiative to create a green credit product to support renewable energy and energy efficiency investments. Loans cover up to 90 per cent of project costs, with costs for audits built in, as well as an associated partial loan guarantee programme for energy equipment which can enable larger-scale project financing.

In the past decade, Central America has improved development policies and regulatory frameworks to promote renewable energy, despite challenges in some countries in relation to the overall investment climate.

Potential social barriers to renewable energy development can be summarised as a lack of awareness of the opportunities for their deployment by the wider public and/or key stakeholders. Three prominent examples are general scepticism towards the feasibility and/or the economics of renewable energy, vested interests in the status quo, and not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) resistance at the project development level.

Renewable energy development is essential to address the region’s key energy challenges, by providing universal access to energy, meeting future demand, transforming the electricity system, and mitigating the effects of climate change.

We can see that increasing policy support, such as the use of energy auctions, has already led to growth in renewable energy capacity in Costa Rica, Guatemala and Panama.

A further development may be solar energy: although wind and small hydropower have received the largest share of investments to date, solar energy is poised for growth in Central America. There are enormous opportunities for future renewable energy development in the region, and domestic and international investors will be increasingly willing to harvest these opportunities if the remaining technical, market, finance, and social barriers can be removed. However, to achieve their full clean energy potential, Central American countries will have to assess and document their renewables endowment, communicate broadly the potential of these assets, and create the necessary financial and political mechanisms for supporting them.

Feed-in tariffs (FITs) and net metering, are both methods designed to accelerate investments in renewable energy technologies by allowing energy producers to be compensated for the energy they feed back into the grid.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025