International offshore wind: Floating offshore wind

Global | Publication | July 2023

Information correct as of 10 March 2025.

Market overview

By some predictions, it is estimated that the UK’s total offshore wind capacity is set to hit 115GW by 2050, with around 35% of installed turbines using floating technologies1. Whilst this places floating offshore wind (FLOW) firmly at the heart of the UK’s decarbonisation goals, the same is true globally. FLOW technology enables access to wind-generated energy at ocean depths of over 60m, a resource that fixed-base wind cannot currently harness. Around 80 per cent of the offshore wind resources globally are located in deep waters and, as a result, floating technology will open up new markets for offshore wind development. FLOW technology is also expected to allow wind generation that is decoupled from weather patterns faced by fixed-base turbines located nearer the shore, smoothing the effects of intermittency.

Early markets will likely include the UK, France, South Korea and Japan…

Although APAC has now surpassed Europe in terms of total installed offshore wind capacity, Europe remains the market leader for FLOW projects. The UK has been an early market-leader in FLOW, and has the largest planned portfolio of announced FLOW projects globally. Pilot projects and pre-commercial sites are now also being deployed in several other jurisdictions, including France, Japan and the USA and the Norwegian government is considering the introduction of a €3 billion support scheme for FLOW in the North Sea. Beyond France, other parts of the Mediterranean region also represent a likely opportunity for FLOW development, with FLOW unlocking offshore wind opportunities for countries like Spain and Portugal, which have deep continental shelves and high wind speeds. In the short-term, Catapult ORE predicts that FLOW deployment will be consolidated in a selection of markets which have benefited from successful pilot projects, touting the United Kingdom, South Korea, Japan and France as jurisdictions looking to deploy commercial scale projects this decade, with 18 further territories flagged as important in the near-term2. In the longer-term, the World Bank has reported that FLOW could swiftly take a leading role in the energy production mix of markets such as Brazil, India, Morocco, South Africa, Turkey and Vietnam, having the potential to add over 2TW to the global fleet in coming decades.

Source: Renewable UK

Domestically, FLOW will likely be a crucial component of the UK’s renewable energy strategy. The UK’s Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero,declared FLOW as being “at the heart of the [UK] government’s mission to make Britain a clean energy superpower”3. Tim Pick, the UK’s previous offshore wind champion, highlights FLOW as one particular area which the UK Government should focus its care and attention, noting the following as key factors to realising FLOW’s potential:

- Supporting innovation to achieve the commercialisation of FLOW;

- Taking a sustainable approach to the CfD auction process; and

- Accelerating investment in port infrastructure4.

The UK Floating Offshore Wind Taskforce's 2050 Vision report similarly highlights five core missions that define the opportunities for FLOW in the UK:

(i) driving cost reduction,

(ii) building a pipeline of projects,

(iii) enabling infrastructure,

(iv) commercialising supply chain opportunities, and

(v) innovating to win.

Whilst it is expected that the main roll-out of FLOW will take place during the 2030s, the 2020s will play an important role in realising the necessary cost reductions required to capture industrial benefits and early mover advantages. In its 2024 “Global Offshore Wind Report”, GWEC anticipates that 8.5GW of installed capacity could be operational by 2030 (although this represents a 22% reduction when compared to the equivalent estimate in their Global Offshore Wind Report for 2023).

Increased investment is expected in the next 12 months…

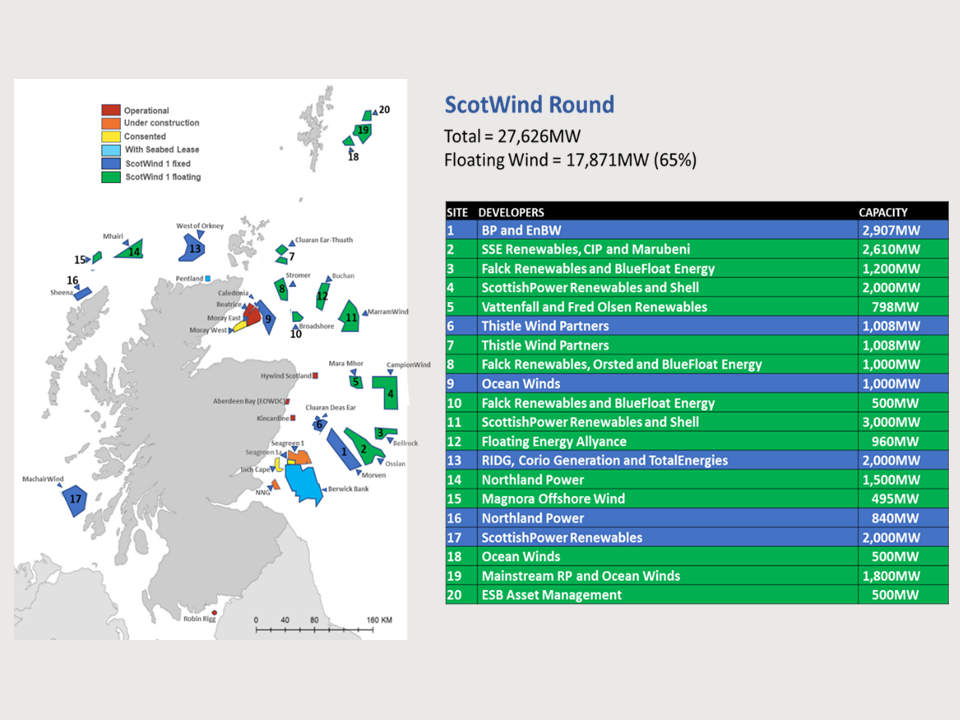

The floating wind industry is a fast developing market, but in order to continue on this trajectory, projects will need to secure the requisite funding. To date, political support and government funding has played a key role in the development of projects. Scotland’s ScotWind leasing round represented the first leasing auction involving sea-bed sites capable of gigawatt scale FLOW projects. Further sites have been made available in Europe through the 4GW Celtic Sea floating wind auction and the Crown Estate’s INTOG leasing round in the UK and the 500MW A06 auction in France. On the face of it, ScotWind was a resounding success story for FLOW, with approximately 65 per cent (over 15GW) of the leasing sites on offer supporting floating technologies (see Image 1 below).

Image 1 - Source: ScotWind - 11GW connected by 2030 | HIE (offshorewindscotland.org.uk)

There is some misalignment in targets being set at a government level…

However, on closer inspection, the ambitious goals of the ScotWind leasing round are at odds with the more conservative targets set by the Scottish government: 30GW and 5GW respectively, each with the same delivery date of 20305. Whilst developers are displaying a keen appetite for FLOW, and investors are spending the time familiarising themselves with the technology, there may still be a lack of clarity at the government levels around consenting and subsidy regimes. Moreover, grid constraints and misalignment between grid applications, permitting and leasing round may compound uncertainty for development timescales and project economics.

In 2022, both The Crown Estate and Crown Estate Scotland entered into “Statements of Intent” with the Electricity System Operator to enable improved coordination between leasing activity and transmission system design activities. The Celtic Sea FLOW leasing is the first auction round to benefit from such improved alignment. For developers to benefit from the same economies of scale as fixed-base offshore wind 20 years ago, the first phase of FLOW projects need to be commissioned with support, with clarity and without delay.

Focus on: Technology risk

The technology used in FLOW is similar in many respects to fixed-base offshore wind; numerous components are directly transferable from fixed-base, and other aspects will only need minor adjustment. To some extent, FLOW technologies can be viewed as a new subset of components being combined with existing turbines, substations and transmission systems. This provides both developers and investors with experience in the fixed-base offshore wind sector with a solid foundation in the deployment of floating technologies. However, technology risk will be one of the key bankability hurdles that developers will need to clear before commercial projects are able to raise debt finance and obtain investment from the private sector.

Fixed-base and floating wind are “parallel industries”…

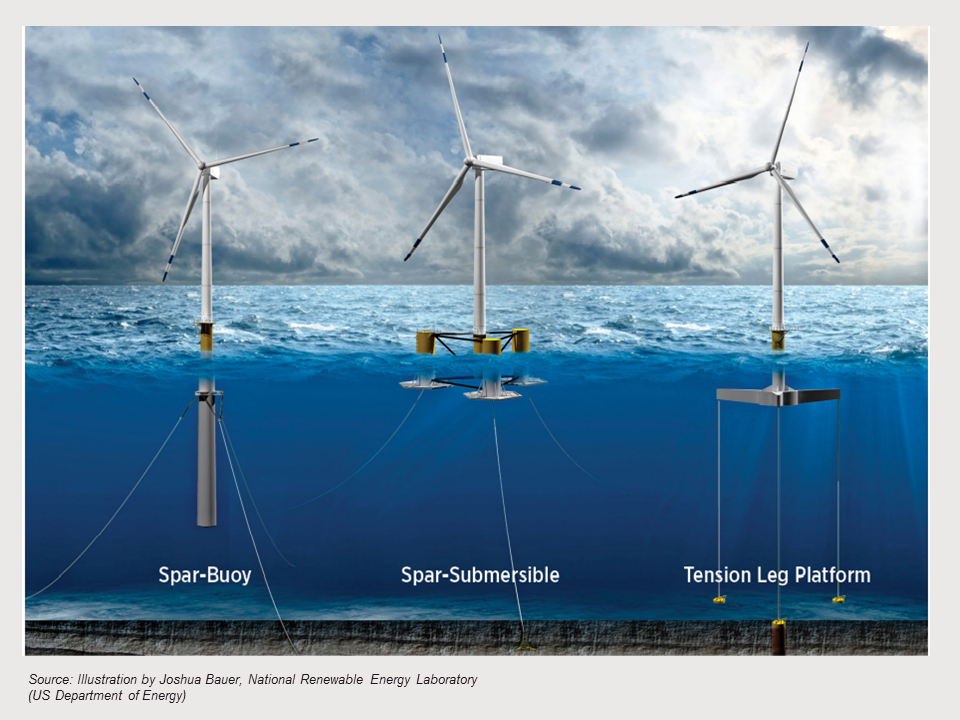

Offshore wind developer BlueFloat Energy has drawn an analogy of fixed base and FLOW as two “parallel industries”, noting that the “development strategy [for FLOW] requires a very different approach and mindset”. One of the notable technological differences is the foundation itself. The choice of floating foundation will depend on the location of the project, seabed conditions, predicted wind speeds and turbine size. At present, there are in excess of 50 different FLOW concepts in development6. Three notable floating structures have been deployed in pilot and pre-commercial projects to date: the spar-buoy, the semi-submersible and the tension leg platform (see Image 2 below). Variations of these technologies are also being developed, such as the mounting of multiple turbines on a single platform, and the barge floating concept.

Image 2 - Source: Illustration by Joshua Bauer, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (US Department of Energy)

This sheer volume of different concepts poses a barrier to cost reductions. It prevents the supply chain from adapting to specific manufacturing requirements and restricts OEMs’ ability to refine components that are being adapted for the floating foundations. Moreover, the configuration of port infrastructure will be directed by the direction of substructure technology, and this uncertainty also limits the ability of banks to mitigate or reduce any perceived technology risks. Once the sector can settle on the most efficient and popular technologies, the FLOW sector will benefit from the standardisation process which has been enjoyed in other mature sectors.

However the future looks bright. Technology development in FLOW is expected to reduce cost, scale production, and broaden applicability over the coming years. The first FLOW wind farms have seen a levelized cost of energy (LCOE) exceeding 200 USD/MWh. However technological developments are predicted to enable FLOW LCOE to drop below 100 USD/MWh by 2025 and under 40 USD/MWh in 20507.

Developers will need to be aware of the bankability challenges of a FLOW project…

Banks will likely focus on the interface between the wind turbine generator and the floating foundation. Robust analysis from the technical advisor in terms of design and load will be required to give potential financiers the requisite level of comfort to fund. Other points of consideration in the due diligence exercise may include:

- the use of novel dynamic cabling;

- turbine configuration and the corresponding risks of inter-array cable failure;

- supply chain challenges; and

- the general uncertainty around the O&M strategy borne out of the limited experience in the sector.

Despite the experience of developers in the fixed-base offshore wind sector to date, many banks have concerns with the lack of a track record for delivering large scale FLOW projects. Early engagement with banks will likely be paramount to managing technology risk for the first projects seeking construction phase financing. An understanding of these risks and their mitigation strategies will be key to unlocking finance.

Generally, FLOW requires larger turbines than its fixed-base counterpart, with structures as tall as 280m. These larger turbines can withstand high wind-speeds and generate higher output per turbine. Despite deployed turbine ratings ranging between 8.5MW and 10MW, turbines with a capacity of 13-15 MW are expected during the course 2025. Capacity factors may also be higher for FLOW when compared to fixed-base offshore wind. The Hywind and Hywind Tampen projects in the North Sea continue to deliver impressive capacity factors and have withstood challenging offshore conditions. This is encouraging, but there remains limited performance data for large scale projects in the sector for the purposes of sizing debt. If developers look to raise third party financing at the commercial phase, input from an energy yield advisor and market advisor will be important, given the likely need for reliance on modelled data.

Focus on: Construction

There are parallels in terms of construction strategy between fixed-base offshore wind and FLOW projects. For example, it is expected that a multi-contract approach will be adopted. This will require focus on factors such as interface risk, contingency in the project budget and buffer in the construction programme – risks that developers and financiers alike will be familiar with. Risk allocation across core packages such as turbine supply will likely remain unchanged. One of the main advantages of FLOW is the ability to carry out important construction works at port rather than at sea (the latter requiring the use of expensive heavy-lift vessels, weather windows and additional equipment). Dry-dock construction enables onshore assembly and allows contractors to tow the structures towards the final destination, potentially resulting in deployment cost savings.

The development of port infrastructure will be key…

The manufacture, marshalling and assembly of the component parts of a floating offshore wind farm requires specialised ports and large storage facilities. Existing ports will need to be adapted and new facilities built at scale in order to meet the needs of the project pipeline across the globe. These upgrades are driven by the deep water requirements at assembly stage and the need for specialised storage space for heavy structures. There is currently a lack of funding in some key markets upgrading existing port infrastructure, and there are insufficient existing ports to meet the current targets for FLOW projects. The Floating Offshore Wind Taskforce predict that approximately £4bn of funding will be required for investment into the port infrastructure required by 20308. Domestically, there have been encouraging announcements recently, including the formation of a National Wealth Fund (NWF). The remit of the NWF is to “invest in the new industries of the future”, which includes £1.8bn of funding to UK port infrastructure and £7.3bn of new funding in total to be invested primarily in green industries. Capital has already started to flow into port redevelopment, including:

- the Port-La-Nouvelle, near Montpellier (France), is one example of repurposing a port which traditionally handled agricultural exports, and €340mn of funding has been raised to transform the port into a hub for the construction of floating offshore wind farms;

- a US private equity fund committed £300m to redevelop Ardersier Port near Inverness (Scotland) to support Nort Sea wind power, whilst it also secured £100m from SNIB and UKIB; and

- Sumitomo Electric has started work on it £350m subsea cable manufacturing facility at Port of Nigg.

Governments will likely be under pressure in the coming years to support investment in the FLOW supply chain and de-risk private investment in key infrastructure. Indeed, there are already some encouraging signs. On 30 March 2023, the UK Government announced the launch of the £160million Floating Offshore Wind Manufacturing Investment Scheme (FLOWMIS) - grant funding aimed at supporting critical port infrastructure that will enable delivery of FLOW projects. FLOWMIS primarily de-risks the development cycle time effects faced by the FLOW sector, engendered by the cautious approach sponsors take to development in light of factors such as late-stage CfD auction announcements and delays in granting leasing rights. In 2024, two ports advanced to the next stage of the FLOWMIS funding process: Port of Cromarty Firth and Port Talbot. The final decisions on FLOWMIS funding were expected to be announced in late 2024, but remain pending as at the time of writing. This funding sits alongside financial commitments from entities such as Associated British Ports which has a £1bn investment plan for Port Talbot to transfer the port into a major hub for FLOW development in the Celtic Sea.

As turbines get larger, companies are likely to encounter economic barriers at the installation phase. The offshore wind sector has arguably suffered from a “race to scale” in recent years, a race that was only compounded when, in October 2024, Chinese wind turbine manufacturer Dongfang Electric Corporation produced a 26MW prototype, with a rotor diameter of 310m. This rapid increase in component sizes compounds issues for developers as there are currently limited options for the installation of larger turbines, the vessels required for such operations are scarce and the rates are expensive. The volume of vessels required to install the mooring and dynamic cables required for a FLOW project will likely place additional constraints on the existing offshore wind supply chain. Further pressure will come from the need for vessels to tow the floating structures to the project site. As a result, there is no clear consensus within the industry as to whether the two-to-shore model is a positive or negative for the FLOW industry when compared to fixed-base technologies. Rystad Energy predicts that demand for these vessels will soon outpace its supply, as more countries seek to build offshore wind farms to meet their net-zero targets.

The distance from shore will introduce new complexities…

Developments in the sector will also create challenges in developing the supporting infrastructure to unlock technological advances. For example, FLOW projects will require more dynamic cabling, including additional wave and impact loads from drifting objects. This increases the risk of cable failure compared to fixed-base turbines. Cable configuration between the arrays will also differ from fixed-base projects, introducing an additional layer of design risk. Deeper waters will require optimised foundation designs, and new installation vessels will be needed to cope with increasingly distant wind farm sites. The proximity of the offshore site to the onshore grid connection point will have an impact on project costs: the further the site is from the shore, the longer the export cables. Distance therefore has the potential to increase capital costs and transmission losses. Novel electrical cable systems may be required to minimise transmission losses and improve reliability, particularly if the transmission distance is greater than 70km. Projects such as Dogger Bank in the UK have already adopted high voltage direct current (HVDC) cables, which will allow developers and investors to get comfortable with the functionality of such assets before they are adopted by commercial-scale FLOW projects.

Focus on: Operation and maintenance

As for construction risk, many similarities exist between fixed and floating projects in terms of routine O&M issues. Many aspects of operations are directly transferable from fixed base to FLOW, such as the management of turbine downtime and contractual framework for the provision of O&M services. These synergies will allow various developers to draw on the lessons learned from experience in the fixed-base offshore wind sector or offshore oil and gas operations. However, there will be some new considerations, such as the handling of major repairs in FLOW. When repairing the gearbox or blades of the turbine, the floating turbine can be disconnected and tugged to shore. This means that repairs could be done portside rather than offshore, making repairs easier to carry out and reducing vessel and helicopter costs (which form a significant part of O&M expenditure.) Advances in technology are also expected to precipitate reduced O&M downtime and decreased annual operational costs. However, in consideration of the O&M tow-back strategy, analysis from BVG Associates suggests that a gigawatt scale windfarm could incur up to seven tow-backs per year as a result of necessary major component changes during the operational phase. Given the cost per tow-back could swell into the millions (GBP), there are some concerns about whether this strategy is truly scalable. Tow-to-shore O&M also requires port availability, which is already limited in today’s offshore wind sector and will be required by FLOW projects in the construction phase.

The primary driver of cost reductions over the next decade will be…

This issue highlights a “known unknown” for commercial lenders who may consider financing the construction and operation of such an asset. There is general uncertainty, borne out of a lack of experience to date, as to what the most efficient O&M strategy will be and what level of contingency will need to be budgeted for O&M expenditure throughout the life of the project. A credit risk analysis will be key to banking FLOW technologies, with insurance cover and performance assumptions receiving particular attention from potential financiers. There may also be limits on key traditional protections such as manufacturer warranties given the extreme offshore environment and less mature foundation designs. Some sources have predicted that operational expenditure for FLOW projects could be significantly higher than fixed-base projects, although this in some cases this is projected to drop to parity by 2030. The primary driver of cost reductions over the next decade is expected to be scaling up turbine size, and therefore overall project capacity. Other factors, such as operational experience and the development of floating infrastructure improvements and technological developments, will play an important role, alongside the emergence of a robust and dependable supply chain. Ensuring that the necessary infrastructure is available to support both the manufacturing of equipment and carrying out the maintenance of the turbine in the operational phase will be important. This is underscored by the pressure that existing infrastructure already faces from oil and gas decommissioning processes and the expanding fixed-base offshore wind sector.

Developers are beginning to collect data on operational performance…

Developers are starting to build the data required to select a preferred O&M strategy. The 25MW WindFloat Atlantic project, which commissioned in 2020, recorded 78GWh of electricity produced in 2022. This represents a 5 per cent increase on electrical output for 2021, and this improvement is partly driven by preventative and corrective O&M activities. WindFloat’s project director, Jose Pinheiro, has highlighted the “additional acquired knowledge to [Ocean Winds]…some [of which is] very valuable and differentiating when projecting future floating commercial projects”. These optimisations will enable developers to collate the reliable data needed to bring pilot projects to commercial scale, which in turn will be crucial to bankability assessments of potential financings.

Focus on: Policy

Despite its potential, FLOW is still significantly more expensive than fixed-base offshore wind. Co-ordinated policy and a clear route to market are needed if the floating wind industry is to achieve full commercialisation in the 2030s. In order to support the build out of FLOW projects, government will need to create certainty through policy and regulatory frameworks, adopting or expanding national schemes such as feed-in tariffs, green certificates and contracts for difference (CfD) to support this new technology. Investors will want to be confident that the policies and targets adopted are party-agnostic and will last beyond the term of the current government. The UK has the largest pipeline globally for FLOW projects, as well as the most ambitious national targets and the highest capacity of FLOW projects, including Hywind and Kincardine9. Policy in the UK therefore serves as a useful case study, as the CfD regime will likely be key to securing the certainty of revenue streams required to attract investment in the sector. As previously mentioned, the UK recently announced its £160million Floating Offshore Wind Manufacturing Investment to support critical port infrastructure that will enable delivery of FLOW projects.

The outcome of AR5 has bearing on the momentum of the FLOW sector…

In the latest CfD allocation round, AR6, FLOW was eligible for up to £270m in the emerging technologies pot, where it competed in a separate pot against other nascent technologies including geothermal and tidal stream technologies. AR6 resulted in the first material CfD award for a FLOW project, as the Green Volt Offshore Windfarm secured a CfD for 400MW of capacity at a strike price of £139.93/MWh. Whilst this price represents more than a 20% saving compared to the Administrative Strike Price for FLOW (£179/MWh), the outcome is a marked increase from the AR4 results for FLOW in 2022. Hexicon’s TwinHub project off the coast of south-west England became the first FLOW project to secure a CfD, when it was awarded a CfD for 32MW of capacity with a strike price of £87.30. The CfD allocation rounds will continue to be tendered on an annual basis, allowing for more frequent CfD awards in the FLOW sector, and therefore a larger pipeline of projects reaching FID each year. Analysis from the Floating Offshore Wind Taskforce suggests that a CfD clearing price below £100/MWh can be achieved by 2030, with further cost reductions enabling a price below £70/MWh by 2050.

The UK government’s consultation on proposed amendments for AR7 concluded in October 2024, when it was announced that the CfD phasing policy which applies to fixed-base projects will be extended to FLOW projects. The UK government has recognised potential ambiguities within the current definition of “floating offshore wind” in the CfD (Allocation) Regulations 2014, which require all turbines to be “mounted on a floating foundation”10. This limitation may restrict projects using innovative foundation designs from competing in the floating offshore wind category. Whilst the UK Government is not making any changes in this regard for AR7, it does recognise the importance of developing a long-term solution to the question of an appropriate definition for FLOW, and this area will remain under review.

Delays to FLOW development will set the sector back further than more mature technologies…

Further progress is required to enable the commercialisation of FLOW by the end of the decade. 4C Offshore warns in its Global Floating Wind Report that targets for 2030 FLOW projects may be missed globally. The cause of the anticipated delays was not reported as supply chain issues or increased capex costs, but delayed authorisation processes. Accelerated development is valuable across all renewable assets, but the benefits are magnified for nascent technologies such as FLOW. Conversely, delays to FLOW development will set the sector back further than more mature technologies. Pipeline size is not enough: for developers to deliver the projects they have committed to, barriers to deployment at the government level must be managed urgently as the halfway point of this decade approaches. Renewable UK (RUK) has suggested previously that sustainable pricing will be key to ensuring that domestic supply chain companies remain at the forefront of developing FLOW technology and ensuring that developers can bid competitively in the emerging technologies pot.

Offtake strategies

In fixed-base offshore wind projects, traditional bankable offtake strategies have involved long term power purchase agreements with a utility, or in more recent years a corporation. From a bankability perspective, importance has been placed on the credit worthiness of the offtaker and the alignment of the contract duration with the underlying debt tenor. Other demand-side drivers may influence offtake strategies, with increased energy consumption stemming from the data centre build outs globally, the potential for a growing international green hydrogen sector and the requirements of underlying lease agreements (as is the case for certain of the UK’s INTOG projects). Whilst this approach is unlikely to change, it is possible that FLOW projects may look to alternative routes to market to compliment, or in some cases replace, more traditional solutions.

A correlation between government FLOW targets and domestic hydrogen ambitions…

Whilst power generation and electricity sales will certainly form part of the picture, it is expected that power-to-X solutions such as green hydrogen may play a part in FLOW’s energy transition role. Various stakeholders are engaged with pilot projects which look to benefit from high generation capabilities of FLOW and located the same close to hydrogen demand centres. This is further demonstrated by the certain of the ScotWind leasing round bids including tie ups with hydrogen electrolyser projects. Similarly, the Sealhyfe offshore hydrogen production facility in France has produced its first consignment of green hydrogen using power from Ideol’s FloatGen prototype 20km off the coast of Brittany. It is likely that there will be a direct correlation between jurisdictions supporting the commercialisation of floating offshore wind and implementing policies with a hydrogen commitment. The Global Wind Energy Council has suggested that “a target dedicated to hydrogen may indicate a preference for relatively high load factor renewables like floating wind”11. To accelerate the deployment of such power-to-X solutions, the development of key infrastructure to support the hydrogen value chain in parallel, along with the success of a form of hydrogen economy, will be crucial.

The conversion of electrons to molecules represents an opportunity for FLOW…

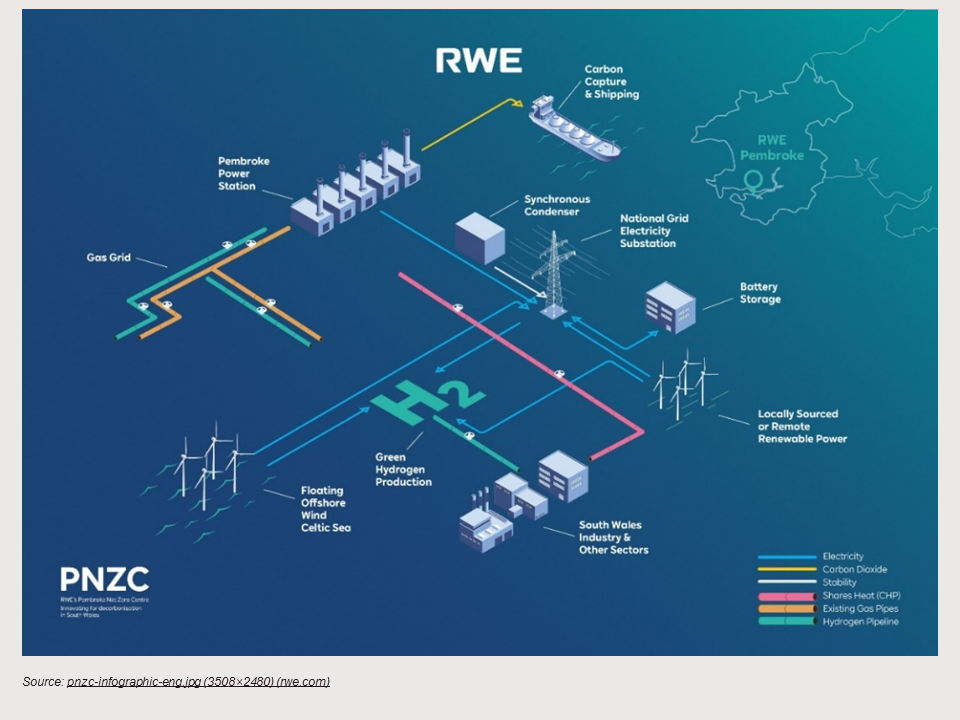

However, it is recognised by many commentators that the economics of using offshore wind to produce green hydrogen at scale will prove challenging. Some of the key ingredients to making green hydrogen feasible include developing a market for hydrogen offtake, building new, or repurposing existing, infrastructure on a large scale, and the presence of a supportive stakeholder group in the sector. The main hurdles for a successful power-to-X strategy will be lowering cost and realising the technological improvements required to make green hydrogen production from FLOW projects viable. The economics of using renewable generation to produce green hydrogen is being tested on smaller scale solar and onshore wind projects, such as NREL’s Wind2H2 demonstration project in Colarado, and although some pilot projects have come up against insurmountable hurdles. In 2024, SSE took the decision to scraps its plans to produce green hydrogen from excess energy production from its Gordonbush onshore wind farm in the UK. Only once there is confidence that the wind-to-hydrogen model is scalable, may this route to market be adopted by fixed-base and floating offshore wind projects. Similarly, RWE’s Pembroke NetZero Centre in the UK, which has the potential to grow to several GW, has links to FLOW in the Celtic Sea (see Image 3 below).

Source: pnzc-infographic-eng.jpg (3508×2480) (rwe.com)

Decarbonizing the oil and gas sector…

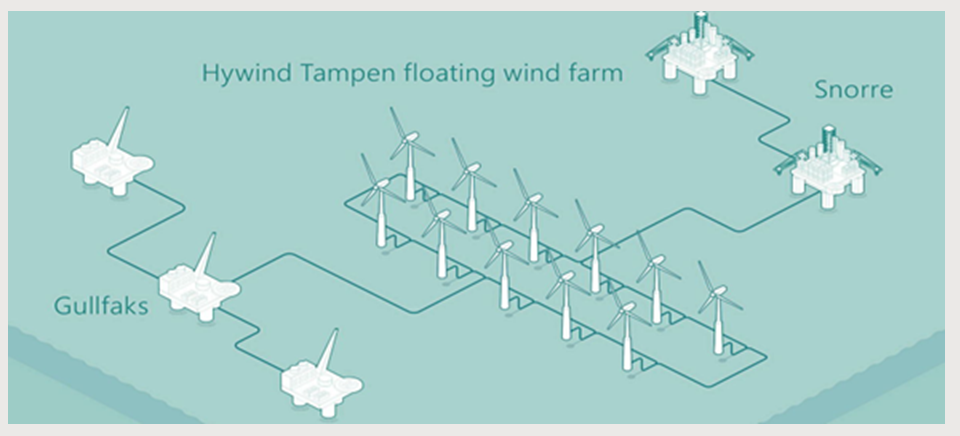

Oil majors are well-placed to capitalize on the development of FLOW because of their technical experience in offshore operations. Considering the prevalence of floating infrastructure in the oil and gas industry, interest from companies like TotalEnergies, Shell, Equinor and Repsol is unsurprising. FLOW can also contribute to lower carbon operations of existing oil and gas fields. For example, Equinor is developing 88MW Hywind Tampen project to supply its Gullfaks and Snorre oil fields with renewable energy to power drilling operations (see Image 4 below).

Scotland’s INTOG leasing round is one example of a policy focused on decarbonising offshore oil and gas production, and an important example of policy-driven innovation in the sector. It was confirmed on 24 March 2023 that 13 projects out of a total of 19 applications (five for “innovation” and eight for “targeted oil & gas”) were offered Exclusivity Agreements following the submission of applications. Since the outcomes were announced, a number of the INTOG projects have progressed: France’s TotalEnergies plans to deploy a pilot FLOW project that will supply around 20% of the Culzean oil and gas platform’s power; Green Volt receive the necessary planning approval in 2024 and Cerulean Winds, which secured three 1GW leases in the INTOG leasing round, has recently selected the port of Ardersier for its projects’ deployment. Cerulean Winds’ founding director, Dan Jackson, has also flagged ammonia and methanol markets as green fuel opportunities for FLOW. These additional markets are given some additional impetus by the current limits on grid infrastructure in the UK and elsewhere, which will not be capable of accommodating surplus power for the foreseeable future. Considering the North Sea Transition Sector Deal in the UK, and ambitious decarbonisation targets set by governments around the world, FLOW is uniquely positioned to reduce the carbon-intensity of existing oil and gas operations.

Market Outlook

The future for FLOW looks positive, but the industry’s success depends on the adoption of supportive policy frameworks, greater public funding, and continued technological development. The cost reductions associated with these factors will be key to the rapid deployment of FLOW globally, and meeting the ambitious targets set by governments and developers for the sector.

By 2050, up to 300 GW of floating offshore wind could be installed globally…

In total, ORE Catapult has estimated that 54 countries pass the initial technical and socio-economic thresholds evaluated for FLOW development. It is also estimated that these identified markets have a combined technical resource potential exceeding 32,000GW and that by 2050 up to 300GW of FLOW could be installed globally12. ORE Catapult have identified four key characteristics of the FLOW markets expected to flourish in the next decade.

- An existing fixed-bottom offshore wind market is key, as such countries are more likely to have a pre-existing framework for the development of offshore projects and an established supply chain.

- The presence of pilot FLOW projects will also boost the likelihood of success, placing countries such as the UK, France and Portugal in an advantageous position.

- Government policy will be pivotal to the success of specific geographies, particularly in terms of obtaining the necessary leasing and consenting rights without delay.

- The supportiveness of subsidy regimes will dictate the level of investor incentive.

Strategic collaborations between developers are starting to emerge…

Experienced developers are beginning to position themselves more aggressively in the floating industry by building their project pipelines and forging alliances with other key players. WindPlus, the collaboration between OceanWinds (a 50:50 joint venture between Engie and EDPR), Repsol and Principle Power, is one example of developers pooling their experience and resources. Similarly the Green Volt offshore wind project, which is expected to be the first commercial scale floating wind farm deployed in Europe once operational, is a 50:50 joint venture between Vårgrønn and Floatation Energy. Some developers are also collaborating strategically to break into specific jurisdictions. RWE has joined forces with the Spanish multinational Ferrovial to develop floating offshore wind farms in Spain. Lastly, collaboration between developers and technology providers, such as Blue Gem Wind (as joint venture between TotalEnergies and Simply Blue Energy), will likely prove a powerful partnership model as preferred technologies begin to take a market share.

Image 5 – Source: Independent Report of the Offshore Wind Champion: Seizing our Opportunities

FLOW is not expected to fully commercialise earlier than 2030 (see Image 5 above for a UK forecast), but for the UK and other early moving markets, the 2020s will be a pivotal period for deploying turbines, proving that the technology is scalable and building a robust and dependable supply chain.

Looking forward to the remainder of 2025, France is expected to launch its tenth call for tenders, which will target up to 10GW of capacity and include three FLOW projects; the Portuguese government recently approved four areas in the Atlantic Ocean for FLOW deployment ahead of the country’s first licencing auction; and FLOW tenders are expected to conclude for the Celtic Sea in the UK and Utsira Nord in Norway. The second half of this decade will be crucial to the successful commercialisation of the FLOW industry globally, and completing the sector’s transition from concept to the mainstream.

Footnotes

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .