Background – LIBOR history and proposed alternatives

What’s the problem with LIBOR?

LIBOR was originally a survey based benchmark, compiled by panels of banks answering the question “At what rate could you borrow funds were you to do so by asking for and then accepting interbank offers in a reasonable market size just prior to 11am?”. In the wake of the manipulation scandal, regulators found that there were very few transactions taking place to support some of the currencies and tenors for which LIBOR was published. As such LIBOR submissions were largely based upon expert judgement rather than transaction data. This led to concerns that LIBOR was unrepresentative and vulnerable to potential manipulation which in turn culminated in a number of criminal actions brought in various jurisdictions around the world.

Regulatory context and initiatives

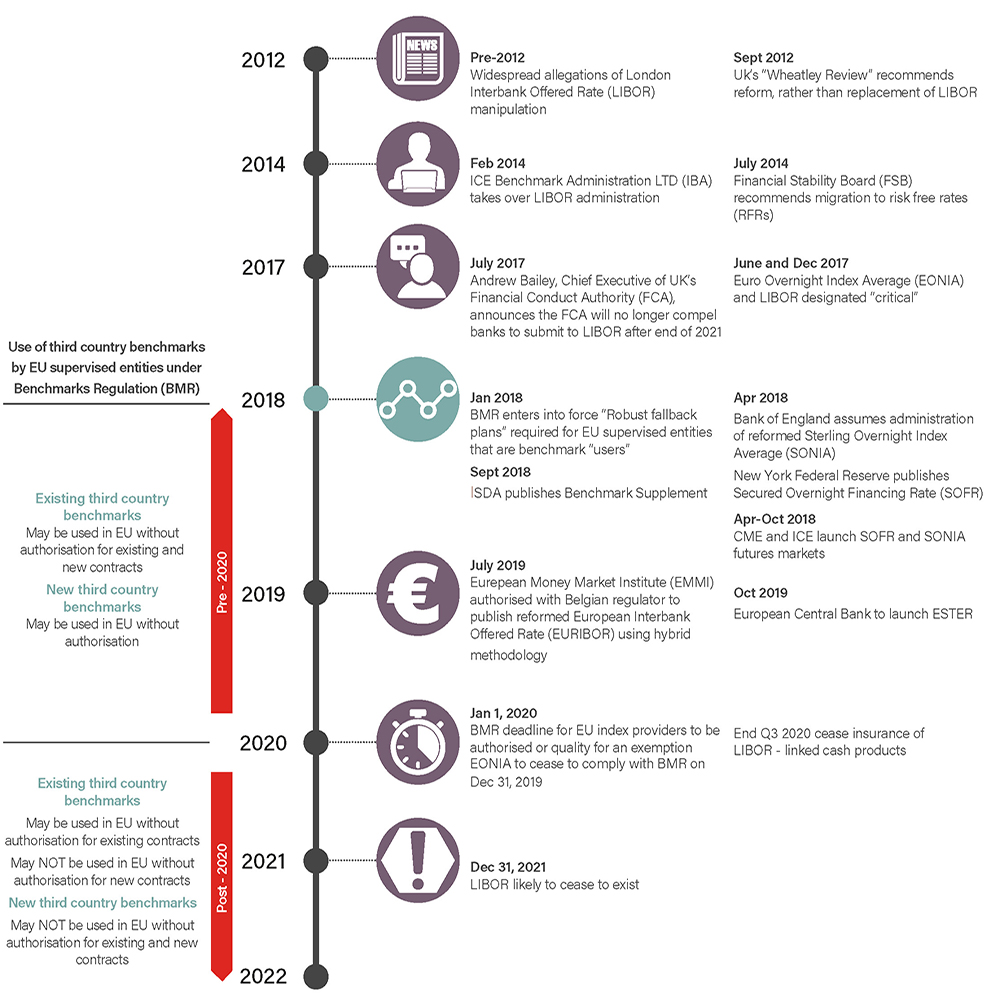

The Wheatley Review of LIBOR in September 2012 concluded that the benchmark rate should be comprehensively reformed. Following the Wheatley Review, the G20 commissioned the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to review and reform major interest rate benchmarks. In July 2013, the International Organisation of Securities Commission (IOSCO) published its "Final Report on Principles for Financial Benchmarks" which set out 19 principles for sound benchmarks which were endorsed by both the G20 and the FSB as good practice for robust reference rates. Using these principles as a framework for reform, the FSB published a report in July 2014 recommending a "multiple-rate" approach with reformed and more robust reference rates that contain a bank credit risk component (IBOR) and alternative RFRs for products that do not require a rate which includes bank credit risk.

What are risk-free rates?

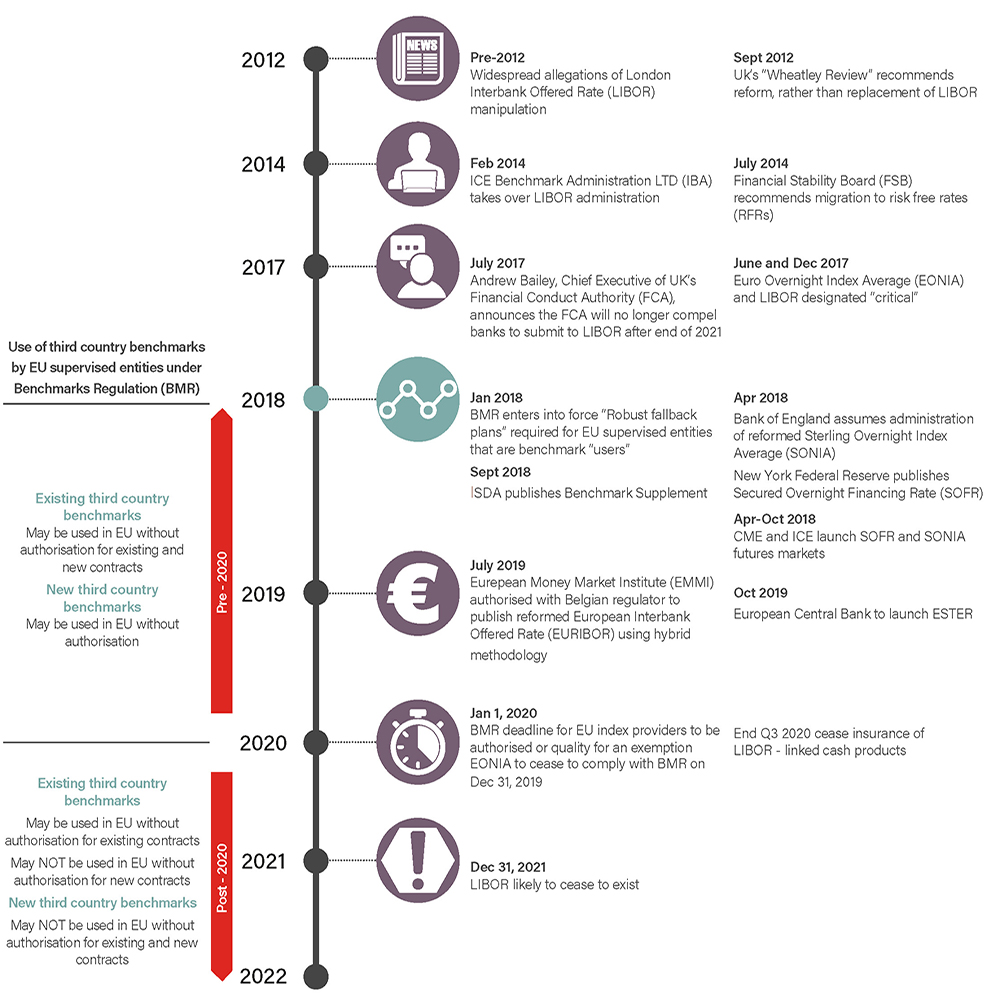

Risk free rates (RFRs) are benchmarks generally based on overnight deposit rates, and are also known as alternative reference rates (ARRs). They are considered to be more robust as they are based upon a larger volume of observable transactions. A risk free rate has been identified for each currency for which LIBOR is currently published.

How are risk-free rates different from IBOR?

Interbank offered rates (IBORs) and ARRs are fundamentally different, with different risk profiles. The key differences are:

- All currently available ARRs are backwards looking (other than for Swiss Franc). They are published the day after the period to which they relate.

- They do not build in the same kind of premium for term or bank credit risk as LIBOR. As a forward looking rate, LIBOR contains an element of pricing based on the notion that one bank is taking credit risk on the other for the relevant tenor. As a consequence LIBOR tends to increase in periods of market stress. This may not be the case with respect to a risk free rate.

- ARRs are administered locally and therefore are published at different times.

Will LIBOR continue beyond 2021?

It is possible that LIBOR may continue for a period post 2021 all be it in a less robust form. For example if LIBOR were to continue on the basis of IBA's reduced submissions policy then this could lock the rate for LIBOR, effectively converting what was a floating rate transaction into a fixed rate transaction. Alternatively the market may move towards an alternative basis for calculating profit prior to the discontinuation of LIBOR and banks may wish to adopt that. As such the Loan Market Association (LMA) has proposed a definition of Screen Replacement Events which include circumstances (such as changes to the methodology for calculating LIBOR and the compilation of LIBOR in accordance with the reduced submissions policy) which would trigger the relevant fallback provisions.

Development of term risk-free rates?

There are concerns that any term based rate would face some of the same challenges as LIBOR in terms of compliance with the IOSCO principles and the EU Benchmark Regulation. In particular, the market for overnight interest swaps (OIS) and futures referencing the relevant benchmark would need to develop to a sufficient size and be sufficiently transparent in order for regulators to have confidence that any such new term rate would itself be representative of the market or economic reality that it was designed to measure. Notwithstanding these concerns, the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC) and the Working Group on Sterling Risk-Free Reference Rates (RFR Working Group) have announced plans to develop forward looking term rates for US Dollars and GBP Sterling respectively.

The ARRC’s recommended alternative RFR for USD LIBOR is the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR). The ARRC anticipates that a term Secured Overnight Financing Rate (Term SOFR) could be developed by using data from SOFR referencing OIS and futures. At present there is not sufficient liquidity within the SOFR OIS and futures market from which a forward looking benchmark could be derived, but this is expected to change. The ARRC anticipates that the private sector may look to develop forward-looking benchmarks on this basis. The ARRC then expect to be able to evaluate such benchmarks and to recommend one such rate which fulfils their criteria. The ARRC has set out a paced transition action plan which it hopes will lead to the establishment of a term Secured Overnight Financing Rate by 2021. Notwithstanding the anticipated development of Term SOFR, the ARRC emphasised in its paper entitled “The User's Guide to SOFR” that market participants should not rely on the development of Term SOFR as a substitute for LIBOR. There is no certainty as to when such a benchmark would be developed (or if it will be developed at all). The ARRC also emphasised that in practice, there was unlikely to be any significant economic difference between a Term SOFR rate and a compounded average SOFR rate.

The RFR Working Goup’s recommended alternative RFR for GBP LIBOR is the Sterling Overnight Index Average (SONIA). On 16 January 2020 the RFR Working Group published a paper entitled “The use cases of benchmark rates: compounded in arrears, term rate and further alternatives”. The paper outlines why the use of Term Sterling Overnight Index Average Reference Rates (TSSR) must be limited while at the same time acknowledging that there are certain financial products where a TSRR would be beneficial. The paper indicates that Islamic facilities would fall within a “product exception” where the use of TSSRs would be appropriate and permitted. This should mean that TSSRs, when available, will be permitted to be used to replace Sterling LIBOR in Islamic banking facilities. It is expected that TSRRs will be published in Q1 2020 for a period of observation with a view to the TSSRs being made available before Q3 2020. It should be noted that there least 4 benchmark administrators who are due to publish their own versions of a TSSR and there are expected to be differences between them. It will take some time for the market to analyse the rates and it will be down to individual banks to determine which rate should be selected.

Issues and potential solutions

ISSUE 1 – Fallbacks

For new facilities, several industry bodies such as the Loan Market Association (LMA) and International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) have published suggested language to facilitate a change in benchmark and to make consequential amendments upon the occurrence of a cessation of LIBOR.

For facilities that do not include such language, documentation may provide that if the screen rate should become unavailable then the change to the calculation of interest or profit provisions and market disruption provisions will apply. Depending on the fallback options selected in a facility agreement, this could involve the interest (or profit) rate being determined by reference to a historic rate, reference banks (who would be very unlikely to quote) and ultimately by reference to a lender's cost of funds. Shari’a compliant corporate facilities typically contain similar fallback options. Where a fallback has been included, there is a concern that LIBOR cessation could trigger a documentary fallback, such as use of costs of funds. This fallback was only ever intended to deal with a short term unavailability of the screen rate and therefore may not be appropriate or a practical proposition for a prolonged period.

There are also legacy transactions which extend beyond 2021 that may not have contemplated a transition away from LIBOR at all.

Where documentation does not anticipate a change in benchmark or the fallback provision is considered to be inappropriate, the basic position with respect to LMA based documentation is that any consent which would involve a reduction in the rate of interest (or profit) will require all lender consent as well as the consent of the obligor(s). If this applies, it will be a matter of negotiation between the parties to the facility documents as to the alternative benchmark and any appropriate spread adjustment.

In the light of the concerns discussed above, there has been some recognition by market participants that it may be advisable in certain circumstances to amend legacy documents so that consequential amendments may be made at a later date once an alternative has been broadly settled in the market – i.e. a two stage amendment process.

ISSUE 2 – Practical issues in using RFRs

One of the key considerations in managing LIBOR transition is market fragmentation and the divergent approaches between industry sectors and currency jurisdictions as to documenting triggers to a replacement of benchmark, fallback provisions, to the method used to calculate any replacement benchmark and to spread adjustment. This needs to be managed with particular care in particular where transactions are hedged given the possible emergence of basis risk.

As RFRs are daily overnight rates, parties will need to agree a methodology to convert that daily rate to apply over a term for a relevant period. Market consensus appears to be settling on RFRs compounded in arrears to produce a backward looking term based rate. Under this approach, the rate for the relevant period is typically determined at the end of the period with a 2 or 5 day look back (i.e. the calculation period for the RFR will start and end either 2 or 5 days prior to corresponding interest or profit period). The practical consequences of adopting this approach are:

- Both the bank and the obligor will not know how much interest or profit will be due until the end of the relevant profit period

- Operational systems are generally set-up on the basis of forward-looking term rates and so will need to be adapted to function with backward looking RFRs

Islamic finance facilities may need to go a step further and change the underlying structure of the calculation of the profit for each profit period (as discussed in Issue 4 - Structural issues for Islamic banking facilities below).

Given the challenges of using a backward looking RFR, many market participants have been hoping for the development of a forward looking term rates which could, like LIBOR, be established at the start of the profit period to which it relates. The concerns with relying on the development of Term RFRs, some of which have already been noted above, are:

- It is not clear that a Term RFR term rate will be available for all currencies

- Where there is an intention to create a Term RFR (noting the examples of Term SOFR and TSSR) it is not certain that such Term RFRs will be available at the time that LIBOR ceases to be available

- If Term RFRs are widely used in Islamic finance while conventional finance market uses RFRs compounded in arrears, there will be divergence between conventional and Islamic facilities. This will obviously make it difficult to compare conventional and Islamic finance on a like-for-like basis and may not be commercially desirable and will also make the agent’s role in a syndicated co-financing with conventional/Islamic finance more complex.

ISSUE 3 – Value transfer and spread adjustment

Where an existing facility will transition from LIBOR to an RFR, the parties will need to determine how to build in an element of term liquidity premium and bank credit risk inherent in LIBOR to avoid value transfer so far as is possible. This will generally mean that a “spread adjustment” will need to be added to the existing margin or profit rate to compensate the bank or financier for what is otherwise likely to be a lower overall rate.

The quantum of the proposed spread adjustment will be a matter of negotiation between the relevant parties, but there are industry initiatives which seek to establish a market consensus on the most appropriate the methodology to be used, the most significant being several market consultations undertaken by ISDA’s. On 15 November 2019 ISDA published a report summarising responses to its consultation on final parameters for the spread and term adjustments in derivatives fallbacks for key IBORs (the Final Parameters Consultation). The report found that a majority of respondents preferred the calculation of a spread adjustment to be based on a historical median of the difference between the relevant RFR and LIBOR over a five-year lookback period (as opposed to the alternative option of a historical trimmed mean over a ten-year lookback period). It is thought that the historical median over a five-year lookback period is now likely to be adopted by the wider market as the default approach for spread adjustment.

ISSUE 4 - Structural issues for Islamic banking facilities

There are concerns within the conventional banking industry that the transition from forward looking LIBOR rates to generally backward looking RFRs create challenges for cash products by making it more difficult for borrowers to know at the outset of an interest period the interest that will be payable on the following interest payment date. While it may be commercially inconvenient, conventional facilities can generally be amended so that interest is calculated and recovered on a backward looking basis. We have seen the conventional market start to move in this direction with strong encouragement from regulators in the UK and US.

Islamic banking facilities typically use cash flows received from an asset or the provision of services to generate a return on the financing that must, under Shari’a principles, be determined at the time the asset based transaction is taking place or the provision of services is agreed. For example, under a commodity murabaha financing, the profit mark-up on the commodity sale from the financier to an obligor must be determined and fixed prior to the sale taking place (i.e. at the start of the profit period). Likewise, under an ijara financing, the variable element of a rental payment must be determined and fixed prior to the start of the rental period. It would not be possible to do this using the compounded in arrears RFRs where the rate for each day in the period would only be known at the end of the period.

Set out below are structural solutions to the issue outlined above. Our focus here is solely on commodity murabaha and ijara based structures, which make up the bulk of Islamic banking facilities utilising floating rates. The simplest documentary and structural solution will be to adopt a Term RFR (e.g. Term SOFR or TSSR) as this would impose the least change on the documents and structure. However, the market would need to overcome the concerns mentioned under Issue 2 above before this can become a reliable option and even if it does become accepted, there will still be occasions where it may not be suitable.

Solution 1 – Calculate the Return on a Backward Looking Basis and Add to the Following Period

Noting that each RFR is a backward looking rate i.e. published at the end of the period to which it relates, one solution is to determine the return at the end of a profit period using the RFR (which would be an accurate calculation) and incorporate it into the amount to be fixed for the next period but stating that this portion of the amount is payable on the first day of that next period. For example, with respect to a commodity murabaha facility, typically at the time of first utilisation a financier would sell commodities to an obligor for a cost price plus a profit mark-up; the profit mark-up representing the LIBOR plus margin profit return on the financing for the first profit period. Since this would not be possible to determine using the RFR, the structure would be amended so that at the time of first utilisation the financier would sell commodities to the obligor for the cost price with no or a nominal profit mark-up amount. At the end of the first profit period, the financier and the obligor would enter into a new murabaha transaction for the same cost price but this time the profit mark-up would be equal to profit return on the financing using the RFR for the first profit period (which would be calculated at the end of the first period on a backward looking basis). The terms of the facility agreement would provide that this profit mark-up would be payable on the first day of the second profit period with the balance (i.e. the cost price) being payable on a deferred basis at the end of the second period. This process would repeat for each murabaha profit period. As market participants will be aware, this backward looking approach is currently used in commodity murabaha facilities to capture any accrued commitment fees.

This solution is, however, not without issues:

- There would be an issue with respect to the profit return on the financing for the final profit period since there would be no subsequent period after that into which this could be captured. In this case, the profit return for the final profit period will have to be included in the profit mark-up for the final period itself. In order to comply with the Shari’a requirement of fixing the profit return at the time of the murabaha transaction, the financier will either need to use a fixed rate to determine that return or then adopt a higher rate and provide a rebate similar to solution 2 below. So, the deferred sale price for the final murabaha transaction would be the aggregate of the cost price plus the profit return for the preceding period plus the profit return for the final period; and

- If the facility needs to be accelerated, the financier would have no claim in respect of the profit return on the financing from the start of the then current profit period to the date of acceleration. A less than ideal solution to this would be to wait until the end of the period, conclude a new murabaha transaction notwithstanding the outstanding default in order to capture this profit return and then immediately accelerate. However, (i) there is no guarantee an obligor will conclude a murabaha in such circumstances; (ii) the financier may not want to wait, particularly if the profit periods are quite lengthy; and (iii) this might not be possible in circumstances such as an insolvency.

Due to these issues, in the case of commodity murabaha facilities, solution 2 may be considered more preferable.

Similarly, under an ijara structure, the variable element of the rental payment corresponding to the first rental period would be nil. For each subsequent rental period, the RFR would be calculated on the last day of the previous rental period and would be payable on the first day of such rental period. This concept is already seen in the market in some multiple drawdown ijara facilities in the form of a true-up rental or additional rental. Unlike the commodity murabaha, there is no concern with respect to the final rental period or any early acceleration since the rental return on the financing for the final rental period or, in the case of an early acceleration, the then current rental period can be captured precisely in the exercise price payable under the related purchase undertaking.

Solution 2 - Rebate Method

A discretionary rebate is a well-established Shari’a concept that is currently used in murabaha financings, primarily in the context of early prepayments under such facilities where a financier may grant an obligor a rebate on the profit-mark up then payable. In Malaysia, the concept of rebates (‘Ibra) is regulated by Bank Negara Malaysia to ensure a consistent approach is taken by Islamic financiers. The rebate concept is used because the profit mark-up payable from both a legal and Sharia’ perspective reflects the profit return on the financing for the entire profit period. However if a prepayment is made at any point prior to the end of that profit period, commercially the parties only intend for any accrued profit to be paid.

A similar mechanism may be adopted to address issue 2 outlined above. A financier and obligor may be able to agree a fixed rate of return (the Headline Rate) determined using a conservative estimate of the RFR based on historical values (or any other methods discussed earlier in this briefing) plus some headroom to give the financier comfort that the Headline Rate should always be greater than the RFR. The financier and the obligor would enter into a murabaha facility using the traditional structure. So, the profit mark-up for any profit period would be determined and fixed at the beginning of that period by reference to the Headline Rate. At the end of each profit period, the financier would determine the actual profit return for that period using the RFR and then grant the obligor a rebate of the difference (if any) between that and the profit mark-up determined using the Headline Rate. An important benefit of this solution is that the issued outlined in respect of solution 1 above do not arise here.

There are however a few points to consider:

- There is the possibility (even if remote) that the Headline Rate could be less than the RFR. The documentation could be drafted such that in any such instance the differential is added to the profit mark-up for the subsequent profit period as per solution 1 above but issues could still arise in respect of any final period or acceleration as outlined in solution 1 above. However, a financier could take the view that based on how they have fixed the Headline Rate that this risk is extremely remote and they can take this risk;

- An obligor may have difficulty agreeing to an obligation to pay a much higher rate and relying on the financier to grant a rebate, especially since the grant of the rebate would (outside Malaysia) be entirely discretionary and not an obligation on the financier. However, this may be something that can be explored with Shari’a scholars to see if a solution can be found that works from a Shari’a perspective and also addresses this particular concern; and

- Both the financier and the obligor would need to assess what the tax and accounting implications of such an approach would be.spect of the profit return on the financing from the start of the then current profit period to the date of acceleration. A less than ideal solution to this would be to wait until the end of the period, conclude a new murabaha transaction notwithstanding the outstanding default in order to capture this profit return and then immediately accelerate. However, (i) there is no guarantee an obligor will conclude a murabaha in such circumstances; (ii) the financier may not want to wait, particularly if the profit periods are quite lengthy; and (iii) this might not be possible in circumstances such as an insolvency.

Whilst we have not seen the rebate concept used in ijara facilities, we do not see why a similar approach could not be taken with respect to the variable element of a rental payment for a rental period.