Features

Essays, stories, prose poems, surveys and critiques

I am an underwater photographer; an amateur.

I dive close to the coral reef, where the fish are.

My dives have taken me to numerous sites but these are my favourites: the tiny island of Malapascua in the Philippines, where, in a dive very early in the morning, I observed a ballet of thresher-sharks; the island of Yap in the Pacific Ocean, where I spent a few dives surrounded by the Manta rays living in those waters; the Komodo archipelago, home to the Komodo dragons, where I saw a marine landscape and richness of diversity more amazing than any I have ever seen; and the Sipadan island off the east coast of Borneo—barely discernible on a map.

The clown fish lives among sea anemones. I find it usually alone or in a family unit.

If I come up close to take a photograph, it will swim very quickly up to my face or mask—as if it were running fast toward me—and then suddenly turn, just before hitting me. It’s like a small dog barking. It’s trying to impress me, to push back.

Some photographers use bulky equipment with special lenses and external lights. Once you are in the water the equipment floats, so you don’t feel the weight. I like to focus on macro photography and prefer to use a small camera which is easy to hold.

You have to be patient if you want to take a good shot. You learn how to remain stable and how to progress with or against the current; you learn where fish are living or hiding in the reef. It takes time to see what’s in front of your eyes, but with each dive your eyes become more attuned.

Underwater, you have a limited amount of air and therefore limited time. The more you move, the more air you consume—I try not to move much at all and to take advantage of the elements and the landscape surrounding me. I try to feel one with the water.

Mandarin fish come out of the reef at sunset. They are very difficult to spot and to photograph—they are very quick, very shy.

They have a beautiful reproduction dance. The male and female swim up away from the coral reef; then, if you are lucky enough, you see them meet for a few seconds; and then they swim away from each other.

I like to talk with local divers and marine photographers during my trips. I am always struck by their accounts of how our marine environment was so much richer in bio-diversity even ten years ago. Our oceans are deteriorating rapidly as a result of our way of living. They observe this— and experience it—every day. Overfishing and pollution are to blame. I have seen this with my own eyes. I have seen fishermen using dynamite to fish in parts of the world; I have seen nets destroying the reef; I have seen entire coral reefs which, because of a change in the water temperature, had died.

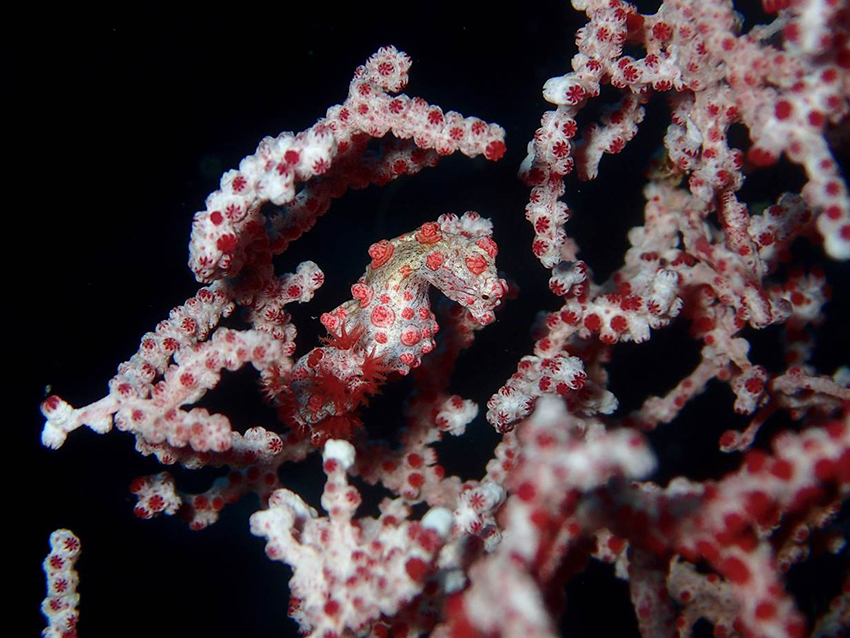

It’s easy to hurt a pygmy seahorse if you get too close or move too fast. It’s not even as big as the nail of a little finger, only a few millimetres in size. When seahorses see me approach they turn their face and show me their back; it is not easy to take a photograph from the front.

Seahorses take the same form and colour as their habitat—the sea grasses, soft coral and sea fans (gorgonians)—and that makes it difficult to spot them. I have on a few occasions seen two or three together; but I usually see them alone. At times, they jump from one branch to another; it’s quite rare to see, but I have seen it.

We have to act, collectively and individually, to protect our planet, our oceans. It’s urgent.

We can start by going out and exploring our own environment, seeing its beauty, whether on the other side of the world or much closer to home. Some countries and international organizations have in recent years created protected eco-tourism areas and marine reserves—places like the Ross Sea in Antarctica and the vast Marae Moana marine reserve at the Cook Islands archipelago in the Pacific Ocean.

The more I explore underwater, the more I love what I see, and want to protect it.

Turtles are suffering from pollution. They take the plastic for jellyfish.

They are a little shy but turtles are not afraid of us. I can get very close. I have been able to look at the turtle from every possible angle. I have looked a turtle in the eye.

Images ©Stéphane Braun, Luxembourg

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025