A night at the opera

In three Acts | The Tale of Januarie | Oedipe | The Exterminating Angel | Issue 11 | 2017

An art essayby Natalia Chudakova

Does the mysterious Russian character really exist? Irrational. Unpredictable. Passionate—and totally unperceivable by the Western world? Or is this just a myth, a comforting excuse for every failure rooted in incompetence and national hoity-toity?

My answer is Yes. Yes, it does exist, and it is about not success, not money, no, it is about a kind of devotion to the purpose of life. When you talk of Russia and its place in human history, you will always speak of culture: music, literature, theatre, art; and here you will arrive at Avant Garde—Russia’s chief export, absolutely unmatched, extraordinary.

The shaking year 2014 was a good time to host an exhibition of the Russian Avant Garde in the heart of Anglo-Saxon London, at the Victoria and Albert Museum. In a year of such political tension, mounting an exhibition like this was always going to be a challenge. But, curiously or not, Russian and British individuals worked in unison, each from their end of the rope, to make it happen.

Human civilisation facing down a catastrophe: this is the climate in which the Avant Garde artists in Russia created their work from 1913 to 1933, and it still resonates today. The V&A exhibition, housed up a flight of stairs in the twisting corridors of the museum’s theatre and performance galleries, presents a dark, rich red space, making me feel almost that I have stepped inside a human heart, filled with presentiment of a coming catastrophe and, at the same time, hope for the future. Both of these are the extreme attributes of the Russian heart.

Speaking about the Russian character, let me tell you a little about Alexey Bakhrushin—Russian philanthropist and art collector, who belonged to one of the five richest Russian families at the beginning of the twentieth century and who lost everything after the communist revolution. ‘Everything’ from the common, tangible point of view, that is; not from his own personal perspective. He preserved the things that mattered for him in life: family, honour, motherland.

Bakhrushin was one of the most talented entrepreneurs of his time; he ran his own leather industry, which prospered significantly in the years leading up to World War I, supplying the Russian army with boots and belts. At that time, Bakhrushin owned a whole street of buildings in the centre of Moscow stretching from his mansion, a neo-gothic palace on Paveletskaya Square, to the crossing with Malyi Tatarsky alley. In 1913, he donated this building along with 1,500,000 exhibits of his precious theatre relics to the City of Moscow.

At the very start of his career as an art collector, Bakhrushin reminded his cousin Alexey Petrovich: ‘Under no circumstances should you leave your collection to your closest relatives…not for the sake of glory and not in search of rewards, but for the benefit of the Motherland and its people, all of our mighty wealth should serve.’

Bakhrushin did not leave Russia after the revolution of 1917, despite the very real danger to his family. He stayed and devoted himself to the chief passion of his life—his theatre collection. He was not killed (as so many others were) but he and his family did suffer, losing all their property and possessions and at one point having nowhere to live. But they survived. And in 1919 Lenin appointed Bakhrushin director of the Theatre Museum, a position that he held until the end of his days.

Bakhrushin’s collection is filled with relics from a dramatic historical period. Through the two centuries when Europe was burning with the fever of industrial and social revolution, a much more important revolution took place in Russia: a revolution in art. This was most strikingly crystallized in theatre, being a concentration of all forms of creativity—music, dance, literature, dramatic art and visual design.

This was the time when theatre became independent, financially and conceptually. This was the time when all extremes of the Russian character burst onto the stage.

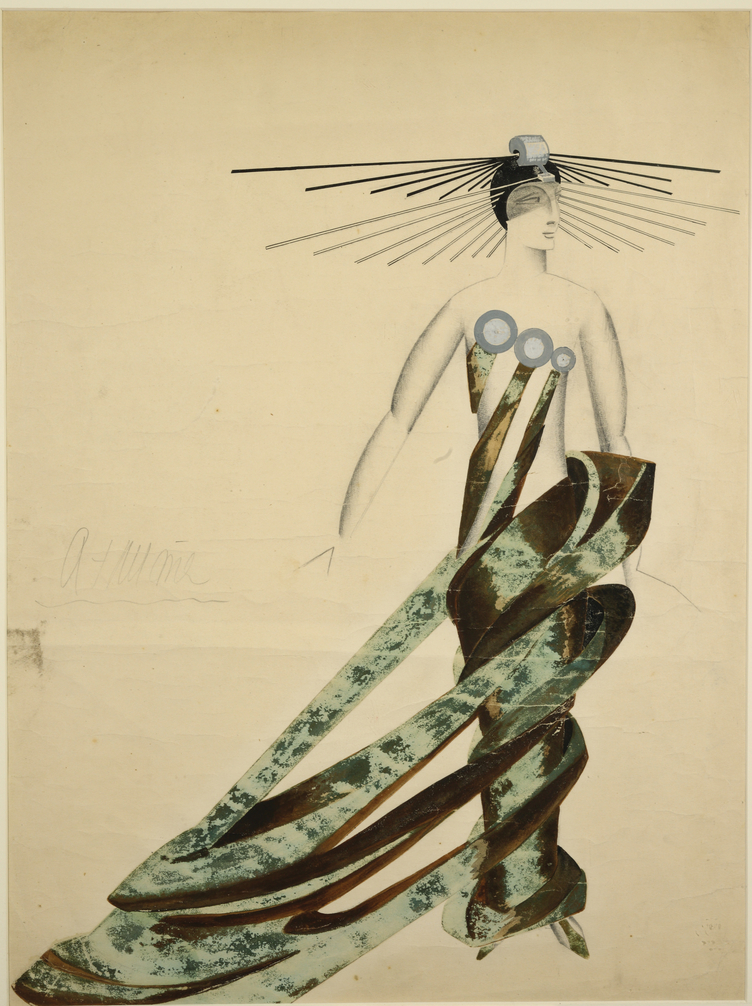

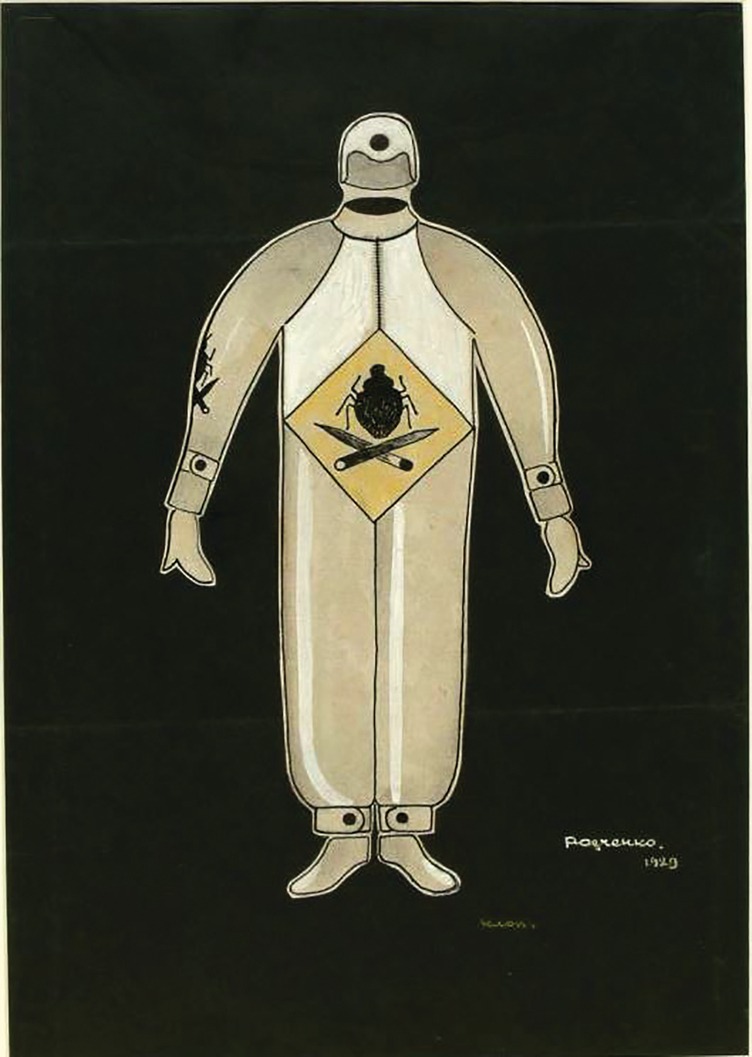

Look at the stage design for Magnanimous Cuckold (1922) by Liubov Popova; the costume designs by Kazimir Malevich for the futurist opera Victory over the sun (1913); the costume designs for The Death of Tarelkin by Varvara Stepanova; or the apocalyptic images by Alexander Rodchenko for The Bedbug produced at the Meierkhold Theatre, Moscow. They are all unique in inventiveness and visual energy and unmatched in their quality.

There is no other nation in Europe where all the leading artists and painters worked for the stage, presenting each of them their own personality rather than that of a particular school or canon.

‘To make an invention one has to start with something that people perceive as an absurd’, Mikhail Larionov used to say to his followers, Malevich and Tatlin. ‘You have to learn from the street boarders, folk amateurs and soldiers who draw on fences rather than from academicians.’

Malevich went on to declare the ‘supremacy of pure artistic feeling’ and he paved the way—through his costume designs using triangles and squares for the world’s first futurist opera—to his famous Black Square painting.

Mikhail Larionov and his wife Natalia Goncharova are perceived as the founders of Avant Garde; even Picasso was influenced by them. And here is an extraordinary phenomenon only typical for Russia. Women artists of that period are equal to men.

You cannot distinguish who is a man and who is a woman without knowing exactly who is the creative artist. This relates to poetry, literature, painting, all the arts. Think of the Russian women poets Akhmatova and Tsvetaeva, the artists Rozanova, Exter, Stepanova, Popova, Mukhina and many others. In the intellectual circles of Russia at the end of the nineteenth century there was no perception that woman is second class.

Avant Garde was about making art without rules, making art without a model and rational structure, giving priority to intuition over skills. This again is one of the main attributes of the Russian character. The sad ending of the story is that this world of striking metaphors was swept away by Stalin’s regime in the early 1930s, bringing tragic endings to the artists’ families and monotony to the cultural landscape. Even more sad to relate is that people’s childlike naivety and emphasis on the idea over the tangible world, so typical of Russians, have always been exploited by ‘the powers that be’.

None the less, rulers will go: and culture stays for ages ever after. Culture is what defines the nation and is the soil from which emerges our growth and development and our individual stories of triumph and success.

Note

Natalia Chudakova viewed ‘Russian Avant-Garde Theatre: War, Revolution and Design, 1913–1933’ at the V&A in London for RE. The exhibition (which ran over 2014/15) presented 150 radical designs for theatrical productions by figures of the Russian avant garde. The works were drawn primarily from the A A Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum (Moscow) and the St Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music. The set and costume designs featured included works created by Kazimir Malevich, Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin, Alexandra Exter, El Lissitsky, Liubov Popova and Varvara Stepanova at a time in Russia in which artistic, literary and musical traditions underwent profound transformations. Artists worked in a number of media including painting, architecture, textiles, photography and graphics.

Opening image

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025