The moving image

Gunnar Benediktsson on Chaplin's little tramp and Paul Klee's 'Angel of History' | Issue 19 | 2021

Image (above) taken from Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night at Tate Britain 2020. Photo: Tate (Seraphina Neville)

Aditya Badami, in London (and Canada) talks about art

Naoshima Island is this remote Japanese island in the middle of the ocean due south of Okayama. It is the pinnacle of all the artistic encounters that I’ve had in my life.

There were maybe a hundred people on the whole island when I went there in 2012. Even to get to the island was a major schlepp: you take a bullet train and then a series of local trains down to the coast and then a ferry that comes once a day. It was really remote.

The grounds were incredible. They had sculptures just on the dock, looking out over the ocean. It is effectively an art island. There’s architecture by Tadao Ando: he is a Pritzker prize-winning, self-taught architect (and an ex boxer and bus driver), who works with concrete and steel and natural light. And then this guy named Walter De Maria, who does these crazy, cutting-edge, abstract sculptural pieces. And James Turrell, the American land artist, who deals again with light and colour.

The highlight was the Chichu Art Museum, designed by Tadao Ando. It is built into a mountain; from an aerial perspective, it’s a series of crevasses through which natural light filters in. This museum has five of the seven or eight waterlilies that Monet did in his late seventies, when he was losing his eyesight. I can still see it in my mind, the room in which those Monets are stored, this massive, massive space, Carrara marble floors and walls, and the attendants all in traditional Japanese garb. You had to take your shoes off, and you’re walking on this cold marble floor, and you can see bare wall and natural light and then again light coming in and finally you enter this room that just has these Monets on the walls. It brought tears to my eyes.

Tokyo itself is beautiful. For such a massive city with so many people, there’s a real, pervasive, aesthetic sensibility everywhere; even the manhole covers have gorgeous art. In the neighborhood I was staying in, Kengo Kuma had built this crazy jutting structure.

Kengo Kuma in Tokyo kkaa.co.jp/works/architecture/asakusa-culture-tourist-information-center/

I was in Calgary until our move two years ago to the UK. Living in London is incredible. I have this rotating list: the Lisson Gallery, the White Cube, the Pace, obviously the major institutional places. During lockdown, every time things lifted, the first thing I’d book would be whatever the exhibition was at all the different galleries. After staring at the screen and the four walls of my office, it was such a delight to see art. It’s so vital.

I’ve done a tour of the Barbican; its history is fantastic. It is purposefully maze-like and built as a fortress. It’s very effective! But I think that’s part of the fun. A recurring theme is from ancient Egypt: these ovalesque shapes—you see them everywhere, the door handles have that shape, the windows are that shape, the windows within doors are that shape.

The space in which the art appears makes a big difference. The fact—and I think about this often—of something being put in a space imbues it with meaning. It’s a lovely thing, to walk through the space; there’s something so essentially mysterious about it. Other mammals don’t do this. They don’t create representational or abstract art and go to look at it.

I like that feeling of smallness that Tate Modern gives you; I quite enjoy that sense of diminishment in the face of something so much bigger than yourself. I love the Rothkos that are housed there—I think they’re in Tate Britain right now, to sit with some Turners.

Rothko at Tate Modern tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern/display/in-the-studio/mark-rothko

The Lisson Gallery represents Anish Kapoor and artists of that ilk. They have two buildings a block apart from each other in Marylebone. They have great free exhibitions. That’s what I like about all these private galleries: they have lots of free exhibitions with interesting, cutting-edge art.

I live in Hackney and there is abundant street art there—it’s very much like Montréal, where I grew up. Montréal has a ton of graffiti. Some people think it’s menacing, that it desecrates architecture; but I just love it, even when it’s ugly.

Montréal has a great art scene. The Musée des Beaux-Arts is fantastic. And the Arsenal has really thought-provoking art. And then if I’m in New York, I go to the Whitney, and the numerous private galleries there. I have a deep hunger to experience art as much as I can. But I’m a total dilettante, let’s just get that out there!

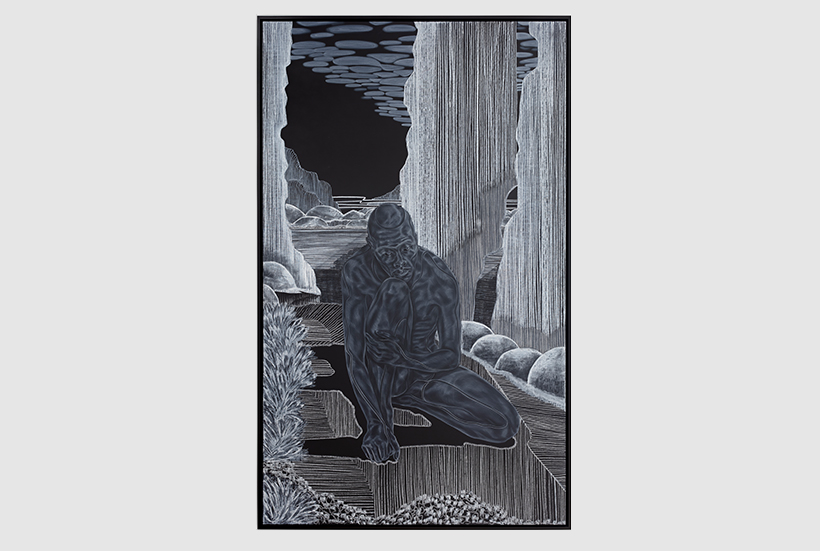

Toyin Ojih Odutola was born in Nigeria, grew up in Alabama and is based in New York. I saw a show by her at the Barbican. It was jaw-droppingly cool. She had worked with musicians to create a soundtrack, and Zadie Smith wrote an essay on the exhibition that was part of the exhibition. It was a series of paintings set out rather like a comic book, but they were large and they were all a meditation on power; it was an imagined world in which those in power were women, and the women power class were slave-owners, and they had imagined this dynamic between the slave-owners and these beings that had been basically bred for servitude. So it was heavy, but incredible and really beautiful.

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Introductions: Early Embodiment (Koba) from A Countervailing Theory (Barbican, 2019) ©Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Toyin Ojih Odutola : A Countervailing Theory | at the Barbican barbican.org.uk/whats-on/2020/event/toyin-ojih-odutola-a-countervailing-theory

The Zadie Smith essay newyorker.com/magazine/2020/08/17/toyin-ojih-odutolas-visions-of-power

And Lynette Yiadom-Boakye is incredible. I saw her at Tate Britain. She did a series of oil paintings of people of Afro-Caribbean extraction in a timeless setting, so you couldn’t place where or when they were from. The figures were all created by her imagination. I just love her work.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night at Tate Britain 2020. Photo: Tate (Seraphina Neville)

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly in League with the Night | at Tate Britain tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/lynette-yiadom-boakye

I have gone out of my way to see James Turrell’s work, in Arizona. He plays with how our brains perceive light. There’s a lot of science behind it, the way he creates apertures, looking into the sky. I saw some of his work on Naoshima Island. It was surreal. He created this pitch black room where you can’t see your hand in front of your face, and you sit at the back, and a light emerges, and you walk towards that light (which the whole time is very diffused and immaterial) and you come to this threshold and reach out, but there’s no wall that you ultimately hit. I really like work like that.

Some art can take you down and down, but that is also a part of life. I went to the Damien Hirst exhibition last year at the Newport Street gallery in London. I know he takes a lot of flak because he’s such a ‘product’, but I actually have a lot of time for his work. It’s great what he has accomplished. But that exhibition was incredibly bleak (it’s all about death); it’s bleak, but it’s also very funny; it’s morbid but funny. He and Tracey Emin came up at the same time, in the late 1980s, early 1990s. They are both subversive in the sense that they force us to confront things that maybe we don’t want to confront, like death; but at the same time, and certainly with Damien Hirst, he has become co-opted by the art industrial complex and is now a multi millionaire machine unto himself—which I can see detracts a bit from the subversiveness. This exhibition went back to his early days, and you could see how that early stuff, even now, is jarring. You can imagine how subversive it would have been back then.

Damien Hirst had another exhibition at the White Cube with giant mandalas made of butterflies. I think he moved from that to painting cherry blossom. That connects to his interest in the natural world and to his ultimate concerns about death. I think that’s at the root of his work, a meditation on death and reproduction; and these manifest in the ephemeral, fleeting things of life, like blossom.

There's a Canadian artist, Kent Monkman, who does these awesome oil paintings reimagining colonial scenes but with his cross-dressing alter ego implanted in those scenes. His work is all about interrogating Canada’s colonial history. Some of the best Canadian art comes out of the Indigenous art culture among the First Nations.

I haven’t mentioned any of the canonical masters, and it’s not that I am not appreciative. I remember seeing a Caravaggio exhibition in London, fifteen years ago, and that was really jaw-dropping. There’s such violence to his paintings. I had a similar feeling with Goya, his nightmare paintings in Madrid, Saturn eating the head of his son!

Goya at the Prado museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/saturn/18110a75-b0e7-430c-bc73-2a4d55893bd6?searchMeta=saturn%20devouring

museodelprado.es/en/whats-on/multimedia/saturn-devouring-one-of-his-sons/3b868e20-2029-426b-849c-86b8db2e2099?searchMeta=goya%20saturn

When I see a Rothko painting I get a chill down my spine. I love that sort of abstract work. But my tastes have changed over the years. Maybe it’s law practice infecting my taste in art. I love Donald Judd, his minimalist art, those very clean lines. And the Canadian, Agnes Martin; she does these gorgeous, delicate grids, very meditative and clean and kind of Zen.

I really like Modigliani’s work, those elongated faces. There’s something unusual about it. Dreamlike. And at the same time very elegant.

I met this artist recently, and this guy had been doing video art for ages and ages, and he was showing me on his phone this augmented reality art that artists are doing now. I couldn’t tell if it was gimmicky or genuinely cool, but either way it’s a start of a whole new world, as we live more and more through our devices. You turn your phone camera on and point it at a flat surface and it’s as though there is a sculpture on that surface that you can rotate and move (like that Pokémon game). Artists have created whole galleries that you can ‘walk through’ with your phone. That was mind-blowing. And disorienting—because I don’t really like looking at my screen.

I love engaging with art and literature and music partly because it enriches your day-to-day experience. When you walk through a park you may see a flower that reminds you of a Georgia O’Keefe painting; it’s like an augmented reality but without your phone. And, going back to the graffiti, I love that need to express ourselves, splash color everywhere.

I work to music all day long, every day. I really like (and I see this more and more) exhibitions that have soundtracks created by the artist.

Putting things in boxes is what we do as humans. We love categorising. And so I respect those boxes. But from an appreciation standpoint, I’m indifferent—I’m totally open and appreciate all of it.

As for my own practice—I take semi-artful photographs that bring me joy. And I had a long period where, when I was stressed out from work, I would draw my hand. I found it very centering and peaceful. I ended up with this notebook that has 200 hand-drawings of just my left hand! When I filled the book, I looked back over it, and I dated everything, and I recycled it—I recycled the book. And that was it.

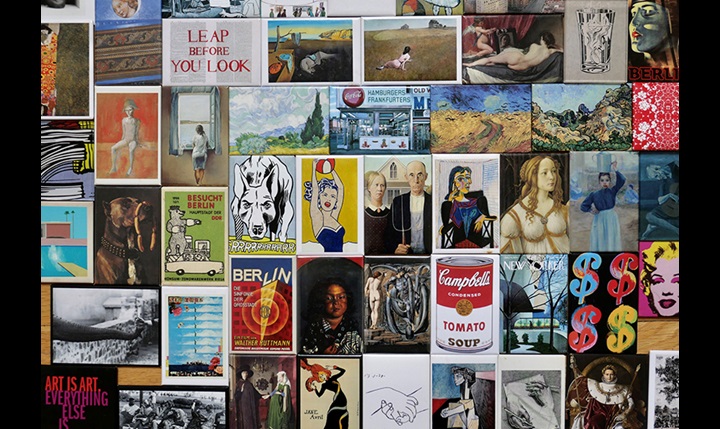

I used to bring fridge magnets back from all the places I went to. I must have a pile of at least fifty fridge magnets.

If I absolutely love an exhibition, occasionally I’ll get the book. I did that for the Lucian Freud show at the Royal Academy in 2020.

Lucian Freud at the Royal Academy royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/lucian-freud-self-portraits

London

barbican.org.uk/

Madrid

museodelprado.es/en

Montréal

arsenalcontemporary.com/

Naoshima

benesse-artsite.jp/en/

New York

whitney.org/

Damien Hirst

Donald Judd

Agnes Martin

Kent Monkman

Toyin Ojih Odutola

jackshainman.com/artists/toyin_ojih_odutola

James Turrell

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

corvi-mora.com/artist/lynette-yiadom-boakye/

jackshainman.com/artists/lynette_yiadom_boakye

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025