Publication

Navigating international trade and tariffs

Recent tariffs and other trade measures have transformed the international trade landscape, impacting almost every sector, region and business worldwide.

Global | Publication | February 2020

Australia became a signatory to The Convention in March 1961. It implemented its obligations under The Convention by enacting the Narcotic Drugs Act 1967 (Cth) (the ND Act). Prior to 2016, Australian law generally considered cannabis as an illegal narcotic. However in February 2016, the ND Act was amended by the Narcotic Drugs Amendment Act 2016 (the 2016 Amendment). Importantly, the 2016 Amendment established a national licensing and permit scheme for the cultivation, production and manufacture of cannabis for medicinal and scientific research purposes. There are other existing commonwealth, state and territory laws that contribute to the regulatory landscape dealing with cannabis which goes beyond the medicinal cannabis scheme.

On January 4, 2018, the Federal Minister for Health (Minister) announced that the government wanted Australia to become the largest exporter of medicinal cannabis in the world. From February 2018, it became legal to export medicinal cannabis products.1 This focused the world’s attention on Australia as a potential major player in the cannabis export market, particularly given Australia’s abundant sunlight and fertile growing conditions. However, the current convoluted legislation impedes Australia’s potential in this emerging industry.

The ND Act required the Minister to cause a review of the operation of the ND Act to be undertaken after the second anniversary of the commencement of the Act.

The review was conducted in March 2019 and a final report (the Report) was tabled to the Parliament in September 2019, highlighting a number of limitations resulting from the 2016 Amendment. The Report recommended 26 amendments to the existing medicinal cannabis scheme and positively, the Minister has accepted all recommendations.2 Several key recommendations are outlined below.

The ND Act fails to differentiate between the psychoactive cannabis component (tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)) and non-psychoactive cannabis components (cannabidiol (CBD) and low THC-hemp). This hinders Australia’s ability to compete in the emerging commercial industry of non-psychoactive cannabis derived products.

The Report proposes to monitoring options to remove unintended obstacles to the cultivation and commercial sale of low THC hemp.

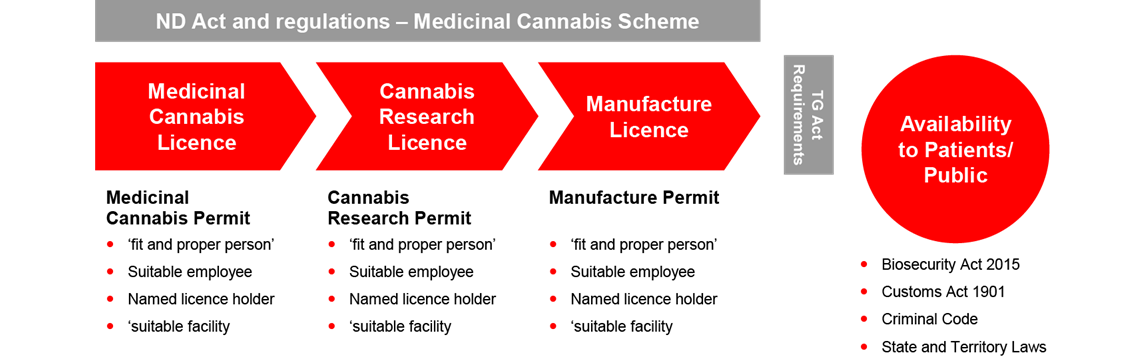

The ND Act and Narcotic Drugs Regulation 2016 (the ND Regulation) creates a regime requiring three licenses, each with related permits for the cultivation, research and manufacture of medicinal cannabis respectively. The license alone does not allow the prescribed activities to be carried and the license holder must also obtain a permit for the licensed activity.

The regime imposes onerous obligations for applicants and increases the administrative workload of the Office of Drug Control. The regime lacks commercial viability for the industry, given that:

The Report recommends the unification of a single license system and the consolidation of requests in the application process. It also recommends that the term of the licenses be extended to five years.

Another critical limitation of the ND Act is its restricted application to the cultivation, research and manufacture of medicinal cannabis without considering accessibility of patients to its therapeutic use.

The Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (the TGA) provides a separate regulatory regime for all therapeutic goods containing cannabis and imposes controls on the quality, safety and efficacy of therapeutic substances that are used in or exported from Australia. The TGA embraces a good manufacturing practice (a GMP) requirement and requires a ‘GMP manufacture license’ for any therapeutic products intended for human use in Australia. This adds an additional layer of requirements that must be satisfied in the manufacture requirements of medicinal cannabis.

The Report recommends better cohesion between the ND Act and the TGA in ensuring patient access for therapeutic purposes.

Recreational use of cannabis in all other states and territories in Australia is illegal, except for the Australian Capital Territory (the ACT).

The ACT government passed legislation to legalize recreational cannabis for adults in September 2019, with the laws coming into effect on January 31, 2020.3 This allows for an individual 18 years or older to possess dry cannabis of up to 50 grams or “fresh cannabis” of up to 150 grams. Each adult may also grow two plants, with a maximum of four plants per household.4

Despite Canberra’s liberalization, recreational use of cannabis remains illegal under Commonwealth law. The arena is currently in legal limbo and we wait to see how police will act in enforcing the law.

The Australian landscape for medicinal cannabis is optimistic and has potential to service the growing commercial industry. However, Australia remains in its infancy regarding medicinal cannabis and its existing regulatory framework requires further review and amendment as evidenced in the 2019 Report.

It still is an exciting time for the industry and Australia will look to other more mature jurisdictions for guidance.

Publication

Recent tariffs and other trade measures have transformed the international trade landscape, impacting almost every sector, region and business worldwide.

Publication

In mid-March 2025, Cognia Law and Norton Rose Fulbright’s Legal Operations Consulting team co-hosted a second roundtable event that brought together senior leaders, including GCs, COO and head of legal operations, from across the legal industry to discuss how to drive meaningful change within the legal ecosystem.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025