Introduction

New research conducted by Norton Rose Fulbright shows that force majeure clauses are already being invoked in certain industries and regions but that this is not yet leading to a domino effect to drag in other industries and regions. Our statistical analysis reveals some intriguing trends on the use of and reaction to the use of force majeure clauses.

‘Force majeure’ refers to unexpected circumstances outside a party’s reasonable control that prevent it from performing its contractual obligations. Some legal systems excuse performance in these circumstances (e.g. France). Although force majeure is not a standalone concept in English law, many English law contracts include force majeure clauses that are intended to achieve a similar result. There is widespread speculation that COVID-19 will lead to parties to contracts invoking force majeure. Companies may be studying their local markets, waiting to see if one counterparty relies on force majeure and if this leads to its use generally. Accordingly, information about how contractual counterparties are acting in the market and what is influencing them is vital.

Norton Rose Fulbright conducted a groundbreaking survey and analysis of the global spread of force majeure in April 2020, showing that force majeure clauses were being invoked in some industries and regions, but that this was not yet leading to a domino effect dragging in other industries and regions. A new update to the survey shows that this remains true, and provides further independent confirmation of the trends we originally identified.

The original survey consisted of 248 individual survey responses from corporates and financial institutions on April 2, 2020. Norton Rose Fulbright conducted a follow-up survey on 27 May, 2020, obtaining a new set of 168 responses. The results of the original analysis were verified for this new set of data. In particular, the main conclusion from the original analysis, that whether a party was considering force majeure depended on whether it had used it before and not on whether its counterparties had used it, was still valid. This is strong additional evidence for the original conclusion and also suggests that this behaviour has not yet changed. Corporates and financial institutions should take account of this market intelligence when managing their own contracts and dealing with their counterparties.

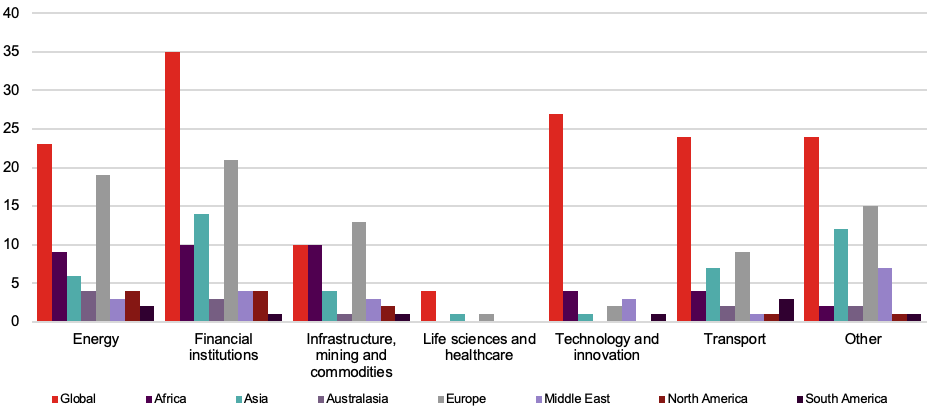

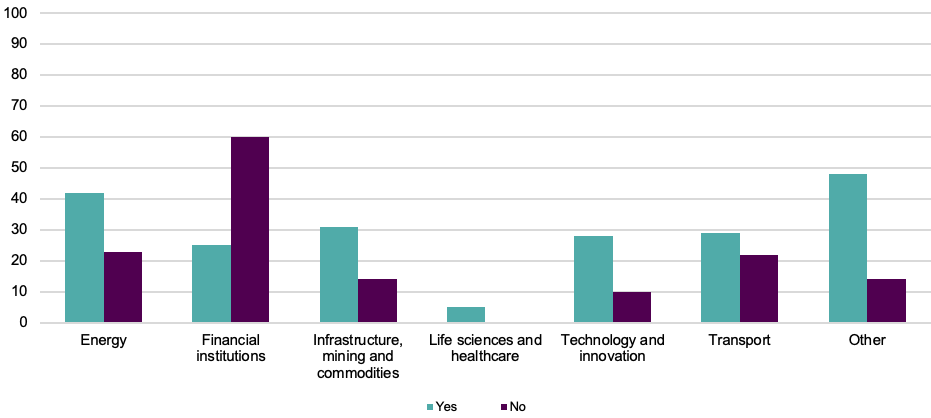

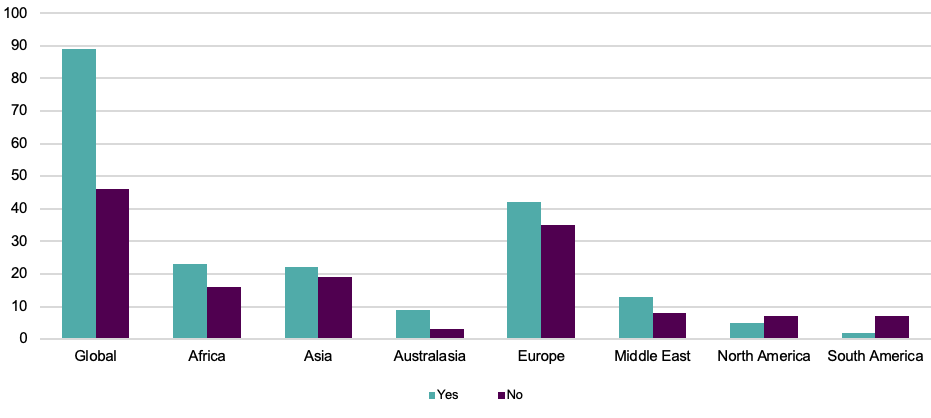

Norton Rose Fulbright obtained 248 individual survey responses from corporates and financial institutions on April 2, 2020. Polling was undertaken with named individuals in senior positions at those institutions, which were spread across different industry sectors and all geographical regions. The industries most represented were finance (24 percent) and energy (18 percent) and the industry least represented was life sciences (2 percent). Respondents operating globally accounted for 42 percent of the total; regions were represented from Europe (25 percent), the highest, through to the Americas (5 percent) and Australasia (4 percent), the lowest. For a breakdown of respondents by location and industry in more detail, see Figure 1.

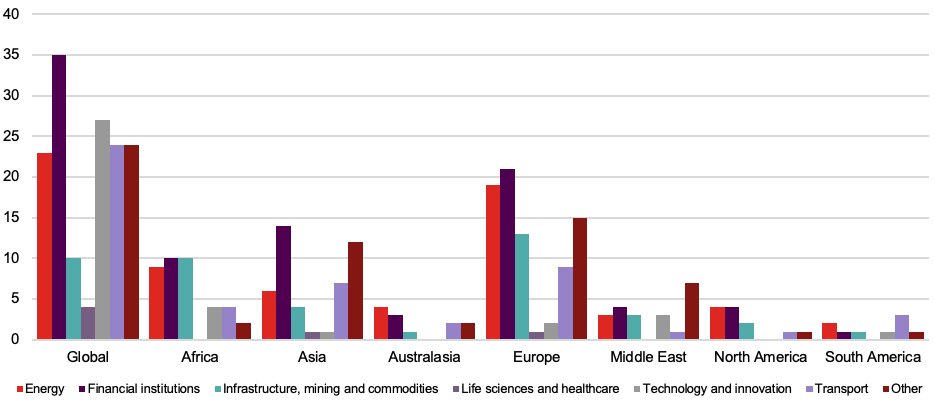

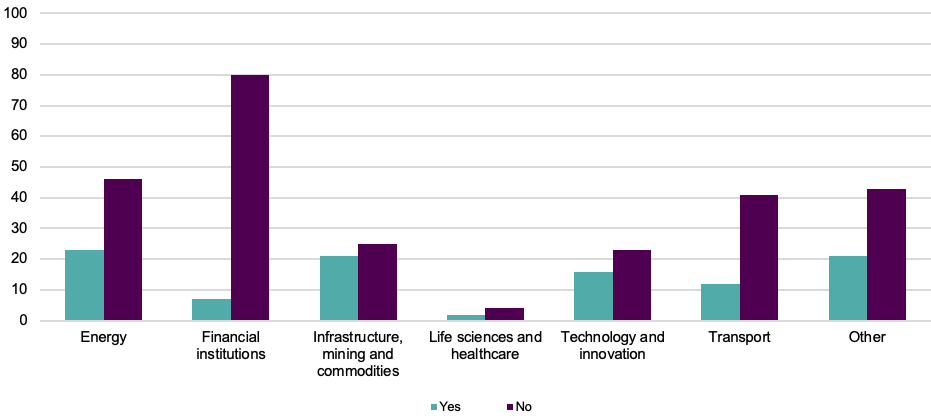

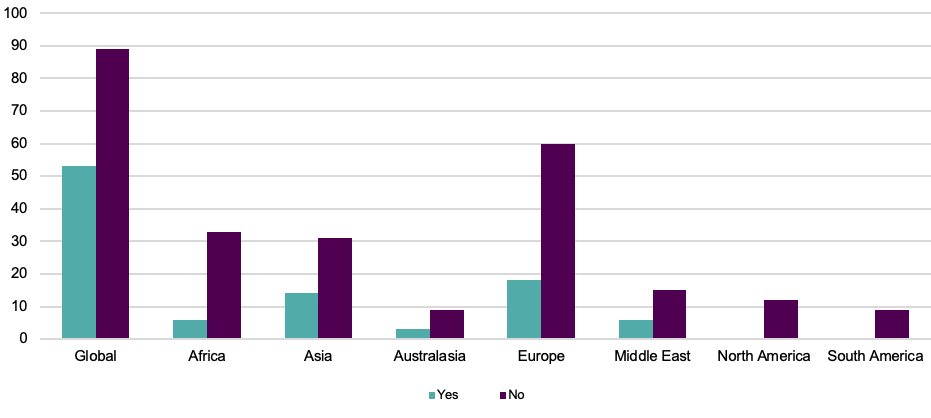

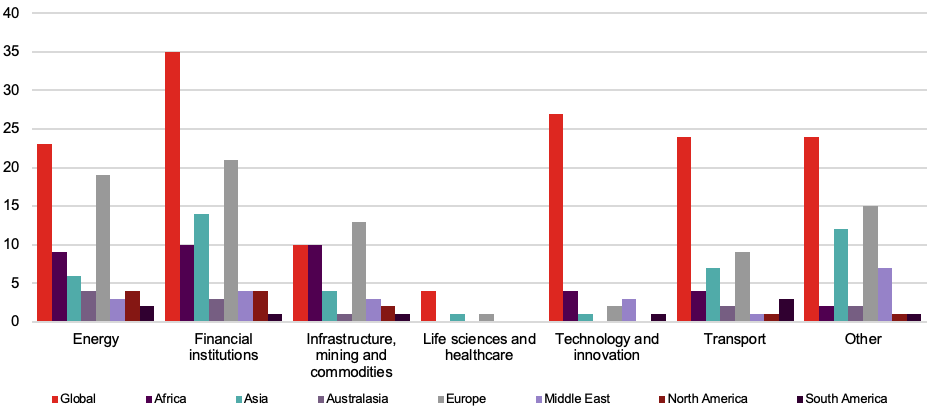

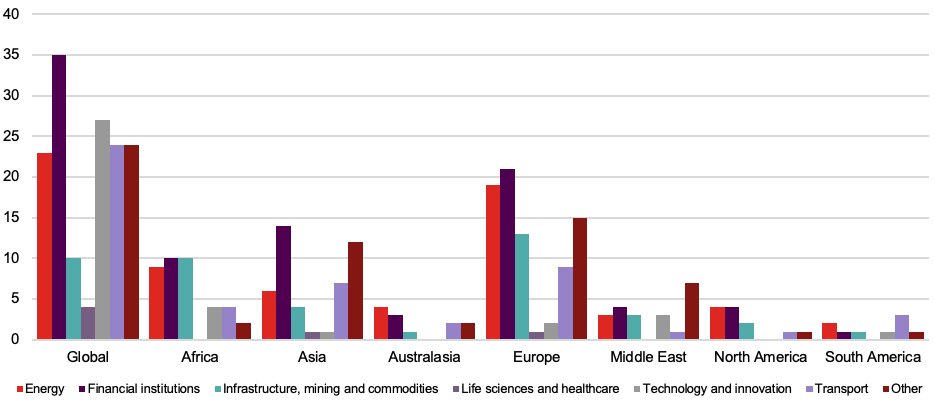

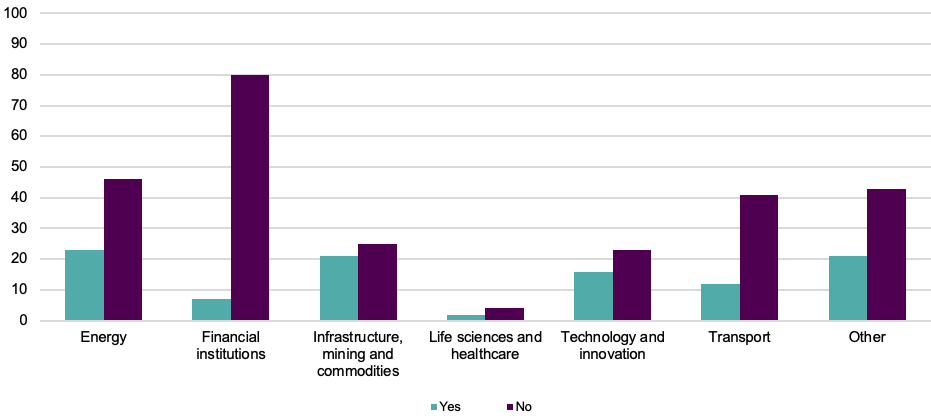

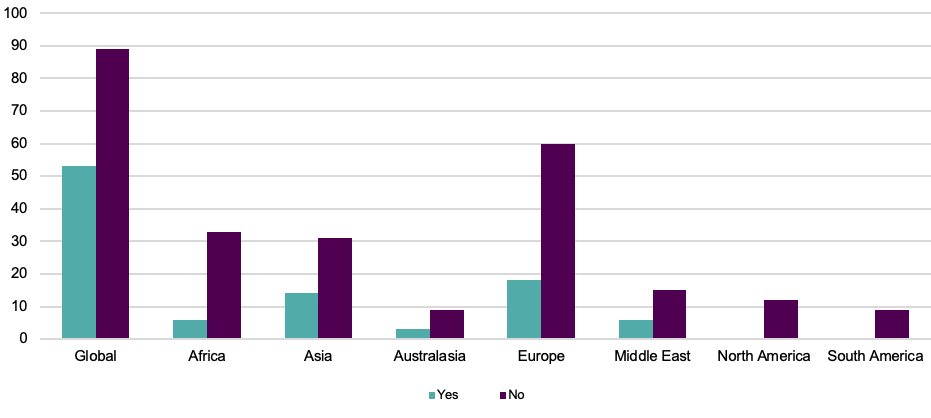

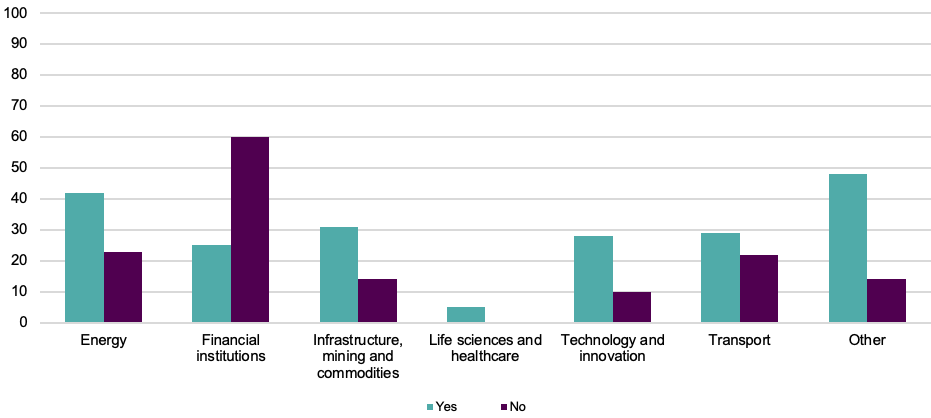

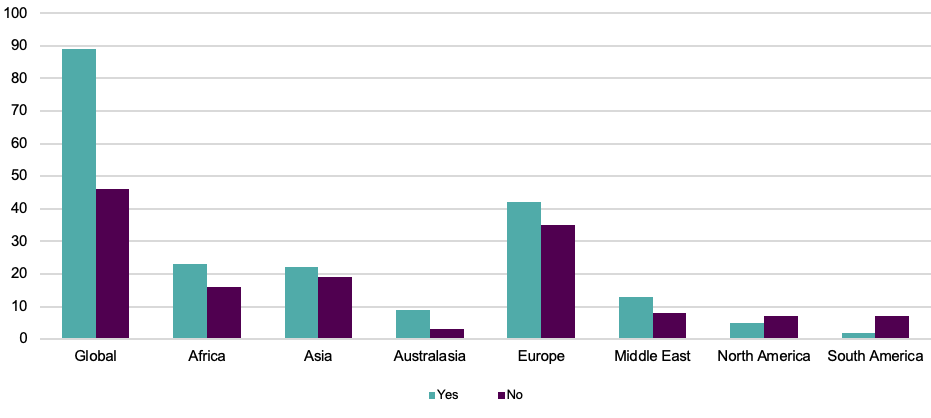

Nearly a third of all respondents had relied on force majeure themselves in 2020 (31 percent). However, just over half had experienced a counterparty relying on force majeure (56 percent) and nearly two-thirds were considering using it in the future (62 percent). For a breakdown of reliance on force majeure and consideration of force majeure usage by both industry and location, see Figures 2 – 5.

The main results of the analysis are as follows (for details of methodology, see the Appendix):

- Financial institutions are less likely to consider using force majeure than contractual counterparties in other industries

Contracts entered into by banks and other financial institutions – such as lending and security arrangements – typically do not contain force majeure clauses, so it is not surprising to see that the finance sector is an outlier with minimal use of force majeure. Unlike during the global financial crisis, difficulties are spreading from supply shocks in the wider economy to the financial sector, not from the financial sector to the wider economy.

- Companies in the infrastructure, mining and commodities (IMC) sector are more likely to consider using force majeure than companies in other industries

IMC contracts may be particularly vulnerable to supply shocks, due to geographically extended supply chains and reliance on local and expat workforces, often in regions with limited infrastructure.

- Companies in Africa, Australasia and Europe are more likely to consider force majeure than companies in other regions

The raw figures for companies in different locations are influenced by which industries are most associated with those regions. But our findings show that, even when comparing companies in the same industry, there is a difference depending on what part of the world they operate in. Companies in Africa and Australasia may be more likely to be associated with parts of the supply chain that have already been badly affected by the crisis or to have extended or vulnerable supply chains. The companies themselves may be more fragile or have less access to financing, making them less resilient and more inclined to consider force majeure. Europe has itself been harder hit by direct effects from COVID-19 and social distancing measures. Underlying agreements in these regions may also be more likely to use governing laws that have force majeure concepts built in, such as certain civil law regimes. This may make invoking force majeure more straightforward than in common law jurisdictions.

- Companies are not more likely to consider invoking force majeure just because one of their counterparties has relied on force majeure

This is possibly the most intriguing finding: force majeure is not automatically spreading up and down supply chains from one industry and region to another. This may reflect the legal risks inherent in triggering force majeure – it may be interpreted by the counterparty as a repudiatory breach of contract if reliance on force majeure is not justified. Disputes are then likely to arise. So, companies may prefer to restrict their use of force majeure to regions and industries where it is already common, calculating that a pre-existing general acceptance that force majeure circumstances exist in the particular market makes a challenge less likely.

- Companies are more like to consider invoking force majeure if they have relied on it before

This is the converse to the previous finding. A good predictor of future behavior is previous behavior. Once a company has evaluated the legal and commercial risks and decided to invoke force majeure, it is then likely to make similar calculations in the future. This may also reflect that many of its contracts are similar and involve similar industries and geographical regions.

Overall, the survey shows a pattern of geographical and sector-specific invocation of force majeure. But use of force majeure does not appear to be spreading merely by contact: what determines whether a company is considering invoking force majeure is not whether one of its counterparties has invoked it, but whether it has relied on force majeure previously itself. So, for now, force majeure remains concentrated within certain markets.

Companies will need constantly to evaluate the legal and commercial risks of force majeure being invoked by them or against them. Legal risks include being found in repudiatory breach of contract for wrongly invoking force majeure; commercial risks include the effect of force majeure on interdependent supply chains. Conformance to market norms is a key overall part of that risk evaluation. Norton Rose Fulbright aims to provide continuing market intelligence, such as by the current survey, to help advise on that risk evaluation and its consequences.

Fig. 1: Survey respondents by location and industry

Fig. 2: Reliance on force majeure by industry

Fig. 3: Reliance on force majeure by location

Fig. 4: Considering force majeure by industry

Fig. 5: Considering force majeure by location

Appendix: Statistical Methodology

Data was analyzed using a multivariate logistic regression supplemented by a random effects model to account for clustering by individual respondent and corporate entity. Calculations were performed in R and the glmmML library was used. There was no imputation of missing values.

Univariate logistic regression was used for initial investigation. Then stepwise selection within a multivariate regression was used to obtain the final model. Robust p-values were obtained by a bootstrapping analysis using the original data. Positive results were reported at a p-value threshold of 0.05, although in practice the largest p-value of all results referred to in the main text was 0.03.