Blog

Squaring the circle: fiduciary duties v economic growth

This is the first in a series of blogs about the Government’s Mansion House reforms, and its goal to get pension schemes doing more for the UK economy.

United Kingdom | Publication | November 2020

* This brief is currently in the process of being updated following significant changes to the scope of reporting required in the UK.

DAC 6 imposes mandatory reporting of cross-border arrangements affecting at least one EU member state where the arrangements fall within one of a number of “hallmarks”. The use of broad categories designed to encompass particular characteristics viewed as indicative of aggressive tax planning follows the approach taken by the UK in implementing its DOTAS regime back in 2004. The hallmarks under DAC 6 are much broader, however, and more parties are likely to find themselves being classed as “intermediaries”, on whom the reporting obligation falls, than is the case with those classed as “promoter” under the DOTAS regime. The potential application of DAC 6 to standard transactions with no particular tax motive creates a difficult compliance burden.

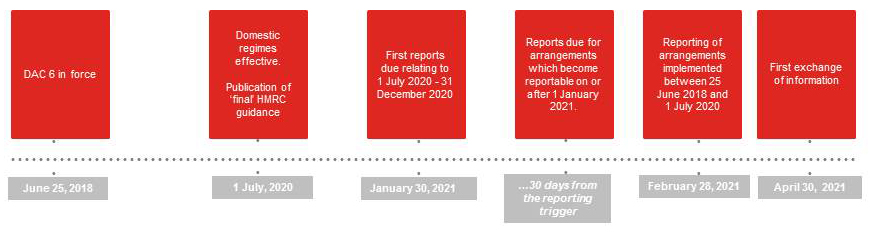

Difficulties have been compounded by the implementation timeline, which provides for implementation with retrospective effect, meaning that the disclosure obligations were “live” from June 25, 2018, before any implementing legislation or guidance had been published.

Reporting was intially expected to start in Summer 2020 but, responding to the challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU introduced an optional six-month delay to reporting deadlines. The UK (and all member states other than Germany, Austria and Finland) implemented this deferral.

The UK implemented DAC 6 via the International Tax Enforcement (Disclosable Arrangements) Regulations in January 2020 with effect from July 1, 2020. The Regulations largely imported the drafting and definitions of the Directive so did not provide much additional clarity. HMRC published final guidance at the start of Summer 2020 and it is this guidance that provides some helpful steers on how HMRC will approach DAC 6.

The cross-border implementation of the regime adds to the compliance burden as the reporting position may need to be reviewed in more than one EU jurisdiction to ensure the domestic rules are aligned. This means that if a conclusion is reached that reporting is not required in the UK on the basis of HMRC guidance, it cannot be assumed that the same conclusion will be reached in other Member States involved; something which seems contrary to the aim of having an EU-wide reporting regime.

It has been clear, since the publication of the Directive in June 2018, that the DAC 6 reporting obligations would be far-reaching and that they would impose a significant compliance burden. What is evident now that DAC 6 has been implemented by Member States is just how problematic the cross-border nature of the regime is and that it may give rise to surprising results.

In a number of areas where concerns had been raised during formal and informal consultation, such as the reporting of standardised products, double depreciation of an asset or cross-border transfers, HMRC are proposing to adopt an interpretation which seeks to limits the potential extent of disclosure. HMRC’s guidance also provides reassuring comments in relation to the extent of an intermediary’s deemed knowledge of the arrangements.

Unless the approaches taken by tax authorities in respect of their domestic regimes are aligned, however, this will not affect whether disclosure is required in another member state. UK resident intermediaries concluding that there is no reporting requirement in the UK may well need to consider the rules in a number of other relevant jurisdictions and make reports in jurisdictions with which they have more limited involvement, adding a significant compliance burden.

Where a report needs to be made and exactly what needs to be reported is far from straightforward. A London branch of an international bank headquartered in another member state is likely to need to report London-arranged transactions in its head office jurisdiction, rather than in the UK. If the arrangement is not reportable in that jurisdiction because of the way that jurisdiction has implemented the Directive, the bank may need to consider the position in the UK (branch location).

The London branch may also be surprised to hear that HMRC do not consider the fact that an arrangement is compliant with the Banking Code of Practice as meaning that it is outside DAC 6. The reporting position of branches of entities headquartered in third states is not consistent across member states. It is a far from straightforward regime to comply with.

Intermediaries have the primary obligation to report. The draft regulations define “intermediary” by reference to the Directive. It includes anyone who designs, markets, organises or makes available or implements a reportable arrangement or anyone who helps with reportable activities and knows or could reasonably be expected to know that they are doing so. The guidance, consistent with the approach identified back at consultation, provides some clarification, identifying two “types” of intermediary.

The first, “promoters”, actually design, market, organise or make available or implement a reportable arrangement. The second, “service providers”, merely provide assistance or advice in relation to those activities.

The key distinction is that a service provider will not be an intermediary if they did not know and could not reasonably have been expected to know that they were involved in a reportable arrangement. This provides an important safety net for service providers involved at the periphery of a transaction. An example given is of a bank providing finance. This is a welcome clarification: the bank is not expected to make a disclosure if it does not have sufficient knowledge of the wider arrangements and, crucially, whether any hallmark is triggered.

Another welcome clarification is that service providers are not expected to do significant extra due diligence to establish whether an arrangement is reportable. The bank, in this example, should do the “normal” due diligence it would do for the client and transaction in question. Of course, remaining willfully ignorant will leave the bank on the wrong side of the “could reasonably be expected to know” test.

Promoters are assumed to understand how the arrangement works so there is no similar exclusion available to them.

A number of the hallmarks only apply if a threshold “main benefit” test is met (see the table below). This is met where one of the main benefits that a person might reasonably expect to derive from an arrangement is a “tax advantage”. The guidance is clear that HMRC view this as an objective test: what matters is whether a tax advantage is the main or one of the main benefits that the person entering into the arrangement might reasonably be expected to obtain from the arrangement. That person’s actual motivation in entering into the arrangement is not relevant. This “main benefit” concept is used in other UK regimes and is notoriously difficult to apply. The guidance (following the same approach as taken in respect of a similar test under DOTAS) views “main benefit” as picking up any benefit that is not “incidental” or “insubstantial”, a low threshold.

The key to applying this threshold test lies in HMRC’s interpretation of “tax advantage” and it’s here that the guidance provides some helpful commentary, in particular noting that the there be no “tax advantage” if the tax consequences of the arrangement are in line with the policy intent of the legislation upon which the arrangement relies. On this basis, HMRC view products such as ISAs and pensions, designed and intended to generate a certain beneficial tax outcome, as not meeting the test unless by reason of being part of a wider arrangement. Similarly, the guidance gives the example of R&D relief which it states would not be caught unless the arrangement attempts to artificially manufacture entitlement.

“Tax advantage” is defined in the regulations as including:

“Tax” for these purposes means any tax to which the Directive applies (i.e. taxes levied by member states other than VAT, customs duties, excise duties and compulsory social security contributions).

This table summarises the hallmarks and, importantly, distinguishes those to which the “main benefit” threshold applies.

| Categories | Hallmarks | “main benefit” test? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category A Commercial characteristics seen in marketed tax avoidance schemes |

Taxpayer or participant under a confidentiality condition in respect of how the arrangements secure a tax advantage. | ✔ | |

| Intermediary paid by reference to the amount of tax saved or whether the scheme is effective. |

✔ | ||

| Standardised documentation and/or structure. | ✔ | ||

|

Category B Tax structured arrangements seen in avoidance planning |

Loss-buying. | ✔ | |

| Converting income into capital. | ✔ | ||

| Circular transactions resulting in the round-tripping of funds with no other primary commercial function. | ✔ | ||

|

Category C Cross-border payments, transfers broadly drafted to capture innovative planning but which may pick up many ordinary commercial transactions where there is no main tax benefit. |

Deductible cross-border payment between associated persons… | ||

| to a recipient not resident for tax purposes in any jurisdiction. | |||

| to recipient resident in a 0 per cent or near 0 per cent tax jurisdiction. | ✔ | ||

| to recipient resident in a blacklisted countries. | |||

| which is tax exempt in the recipient’s jurisdiction. | ✔ | ||

| which benefits from a preferential tax regime in the recipient jurisdiction | ✔ | ||

| Deductions for depreciation claimed in more than one jurisdiction. | |||

| Double tax relief claimed in more than one jurisdiction in respect of the same income. | |||

| Asset transfer where amount treated as payable is materially different between jurisdictions. | |||

|

Category D Arrangements which undermine tax reporting under the CRS/transparency. |

Arrangements which have the effect of undermining reporting requirements under agreements for the automatic exchange of information. | ||

| Arrangements which obscure beneficial ownership and involve the use of offshore entities and structures with no real substance. |

|||

|

Category E Transfer pricing: non-arm’s length or highly uncertain pricing or base erosive transfers. |

Arrangements involving the use of unilateral transfer pricing safe harbour rules. | ||

| Transfers of hard to value intangibles for which no reliable comparables exist where financial projections or assumptions used in valuation are highly uncertain. | |||

| Cross-border transfer of functions/risks/assets projected to result in a more than 50 per cent decrease in EBIT during the next three years. | |||

The consultation comments on each category of hallmark.

The “generic hallmarks” (confidentiality, fees based on tax advantage obtained, use of standardised documentation) are all subject to the main benefit test. HMRC view the Category A hallmarks as similar to several hallmarks under DOTAS and indicated at consultation that they intend to take a similar approach in interpretation.

Specifically, in respect of standardised documentation, the guidance notes that under the equivalent DOTAS rules, arrangements such as ISAs and enterprise investment schemes are excluded. There is no express exclusion under the regulations on the basis of HMRC’s view that these kinds of products are not inherently caught by the main benefit test.

Again, these are all subject to the main benefit test. The most widely discussed of these is Hallmark B2 which captures arrangements which have the effect of converting income into capital (or other categories of revenue taxed at a lower rate). Here the guidance treads a very fine line between situations where HMRC perceive that a conversion from income to capital has taken place and those situations where there is a legitimate commercial choice to be made between different commercial options. This is an area where further examples would be welcome although analogies can be drawn. One example given is of employees given EMI share options as part of their remuneration where any increase in value in the share options before exercise could be taxed as a capital gain rather than income. Whilst the employee could have received salary income instead, the employer has simply chosen between viable (normal) commercial options. Other examples pick up pre-liquidation dividends, company sales where the sale price includes accumulated earnings, share buybacks and the issue of securities which qualify as “Excluded Indexed Securities” under UK law. The addition of steps which are contrived or outside normal commercial practice would be more likely to bring the arrangement within the hallmark. A point to note here is that “conversion” of income into capital does not necessarily require any pre-existing right to income.

The guidance provides some useful clarifications in relation to Hallmark C1 (cross-border payments between associated persons)

A number of practitioners had questioned whether Hallmark C2 (requiring disclosure where depreciation is claimed in more than one jurisdiction) would lead to an absurd result where assets are acquired by branches, due to the inclusion and credit basis on which permanent establishments of UK entities are taxed. HMRC addresses this: arrangements will not be reportable where there is a corresponding taxation of profits from the asset in each jurisdiction where depreciation is also claimed (subject to any double taxation relief). Whilst this is not strictly in accordance with the drafting of the directive, which contains no such carve out, this is a welcome approach from HMRC as it will enable commercially-motivated transactions to proceed without the risk of being tainted by disclosure.

This hallmark looks at arrangements which have the effect of undermining CRS reporting or obscuring beneficial ownership. There is no main benefit test and the test is stated to be an objective one, so that the intention of the taxpayer is irrelevant. Having said this, the guidance is clear that arrangements which merely lead to no report under the CRS being made will not be undermining or circumventing the CRS provided that outcome is in line with the policy intentions of the CRS (the example given is using funds held in a bank account to invest in real estate, a category of investment specifically excluded from reporting under the CRS). As is often the case, the examples do not directly address grey areas. Advising a person to transfer funds to a jurisdiction which has not implemented CRS, in order to avoid reporting will, not surprisingly, be caught.

Here again the guidance anticipates that “promoters” will know whether arrangements undermine or circumvent CRS whereas a “service provider” may not only have knowledge of a particular step and may not understand the effect of the arrangement as a whole, so may not be under an obligation to report.

The test at Hallmark D2 (arrangements obscuring beneficial ownership) is whether beneficial owners can reasonably be identified by relevant tax authorities, including HMRC. This does not require a public register of beneficial owners but, where there is a public register, the hallmark will clearly not apply. Examples of obscuring beneficial ownership include the use of undisclosed nominee shareholders or of jurisdictions where there is no requirement to keep, or mechanism to obtain, information on beneficial ownership. Helpfully, the consultation states that, as with the OECD’s Mandatory Disclosure Rules (MDR), institutional investors or entities wholly owned by one or more institutional investors are outside this hallmark.

Responding to questions raised during informal consultation, HMRC’s guidance confirms that APAs are not unilateral safe harbours (but rather agreements as to correct pricing) and are therefore not caught by this hallmark.

Other comments of interest relate to Hallmark E3 (intragroup cross-border transfers). This hallmark applies where a cross-border transfer of functions/risks/assets is projected to result in a more than 50 per cent decrease in EBIT of the transferor(s) over the next three years. HMRC’s starting point is to consider this test at company, rather than group level (as that is how the UK corporation tax regime works) but there is acknowledgment that many other jurisdictions have tax consolidation regimes and may take a different approach. The test looks at projected earnings, not what has actually happened: if the projections used in reaching a decision not to report are what a hypothetical informed observer would consider reasonable, there is no failure to comply whatever the real-world outcome. HMRC expect relevant entities to be producing the kind of projections required to apply this test and would not expect the taxpayer to need to make any special calculations for DAC 6. There are a number of grey areas despite some helpful commentary on what will and will not constitute “cross-border”. Exactly how this would apply (and whether it would apply) to a number of common transactions, including an intra-group hive-up of shares, is unclear.

The regulations cross-reference the list of reportable information set out in the Directive and clarify that, to be reportable by an intermediary, information must be in the intermediary’s “knowledge, possession or control”. The guidance expands on this: an intermediary is not required to trawl through all of its computer systems to try to find all information held in relation to the relevant taxpayer in order to see if it might be relevant, but the intermediary will be expected to review the documents and information in relation to the reportable arrangement.

This is a lot of detail. Whoever is making the report will clearly need to devote time to collating information

The Directive sets out a hierarchy to determine which member state a disclosure should be made in and this hierarchy is cross-referenced to in the draft regulations. The starting point is that the report should be made in the member state in which the intermediary is tax resident, failing which, in the location of a PE connected with the provision of the relevant services and, where neither apply, in the place of incorporation or, ultimately, in the member state where the professional association with which the intermediary is registered is located.

A transaction is likely to involve a number of intermediaries. Disclosure only needs to be made once in respect of arrangements.

This means that no report needs to be made in the UK if:

In either case, the intermediary needs to be able to evidence that the information that it would have been required to report has been reported, not simply that a report has been made. The guidance does not provide suggestions as to how the intermediary achieves this. The expectation is that the filing of a report will be evidenced by providing the “arrangement reference number” provided by HMRC or the relevant competent authority in other member states but provision of the ARN does not mean that HMRC accepts that the report is complete or accurate. Determining whether the report made was comprehensive may be left to the intermediaries to work out between themselves. An intermediary who has made a report and subsequently realises it contains inaccuracies is able to return to it and make amendments.

Documented formal agreement as to who will make the report should be in place before the actual reporting obligation commences. It will be beneficial in transactions where disclosure is thought to be necessary to ensure that all parties involved are able to cooperate with the reporting process so that a single, comprehensive report can be submitted. Parties involved will want to consider rights of review and comment and will need to ensure that the making of the report will not breach any contractual terms, including terms of engagement. It may become common practice in certain types of transaction to agree contractually who will undertake the reporting obligation and in what form.

An intermediary unable to report due to legal professional privilege is required to inform other intermediaries of the fact and of their reporting obligations. As would be expected, this does not provide a blanket exclusion from a requirement to report: legal professional privilege only applies to information that is legally privileged. The guidance is clear therefore that lawyers may need to report any information that is not privileged in nature. The Law Society has published guidance which sets out its view on when this might be the case and situations are clearly very limited. In practice, intermediaries may agree between themselves that reporting will be undertaken by an intermediary not subject to legal professional privilege who can make a single report including all the required information. No doubt the boundaries of this rule will be tested over time.

The penalty regime draws on DOTAS and provides for penalties in a number of areas. The starting point for failure to report penalties or a failure to notify of reliance on legal privilege is a default penalty of £5,000 or, if HMRC consider this too low (perhaps due to deliberate or repeated failure or where the failure has serious consequences), the First-tier Tribunal can impose daily penalties of up to £600 or, as under the DOTAS regime, if the First-tier Tribunal considers this inadequate it can impose fines of up to £1 million. There are also penalties of £5,000 (rising to £10,000 per arrangement for repeated failure) for failure by a relevant taxpayer to make an annual report in respect of any arrangement in any year in which it obtains a tax advantage in respect of the arrangement or to make three-monthly returns in respect of marketable arrangements.

A penalty will not be imposed where a person has a reasonable excuse for failure to report. In evaluating this, HMRC will consider whether a person has “reasonable procedures” in place to ensure that they are able to meet their obligations under the regime (and has taken reasonable steps to ensure those procedures are complied with). As is in the case in other regimes where this defence is available, what is reasonable will depend on the circumstances and having procedures in place will not automatically mean that no penalty is due (repeated failures, for example, may indicate that procedures are not adequate and steps should have been taken to address potential gaps).

There is acknowledgment of the challenges faced by taxpayers in the period between June 25, 2018 and the publication of the Regulations and guidance. Where a failure relates to an arrangement where the first step of implementation predates the publication of the final Regulations in January 2020 and the failure was due to a lack of clarity around the obligations or interpretation of the rules HMRC anticipate some leniency.

Blog

This is the first in a series of blogs about the Government’s Mansion House reforms, and its goal to get pension schemes doing more for the UK economy.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025