The historian

David Francis on PEN and the Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka

RE | Issue 15 | 2019

‘The spirit dies in all of us who keep silent in the face of tyranny.’

This is the dedication inscribed on a PEN International memorial which I came across last year in a grove of trees beside Lake Burley Griffin in Canberra. I write fiction. I also co-chair the US west coast branch of PEN America, the largest of over a hundred PEN centers worldwide. So this chance encounter had real resonance for me.

PEN exists to give writers a voice, to provide for intellectual exchange and to promote freedom of expression for all writers—regardless of nationality or race or religion or the political system under which they live. The acronym originally stood for ‘poets, essayists, and novelists’ but now includes playwrights and editors among that number.

PEN was founded in London a few years after the devastation of the First World War; its first president was John Galsworthy, the Nobel Prize-winning author of The Forsythe Saga. The writer of The War of the Worlds, H.G. Wells—who later campaigned against the burning of books by the Nazis—was one of PEN’s early members. He was in good company: other members in the 1920s included Joseph Conrad, Elizabeth Craig and George Bernard Shaw.

By the late 1930s, PEN was active in protesting against negative treatment of writers and appealing on their behalf. One notable case was that of Hungarian-born Arthur Koestler, who was working in Spain as a foreign correspondent in 1937 and was imprisoned and sentenced to death by Franco’s nationalist forces. Koestler was freed after PEN vigorously campaigned for his release. He went on to write Darkness at Noon.

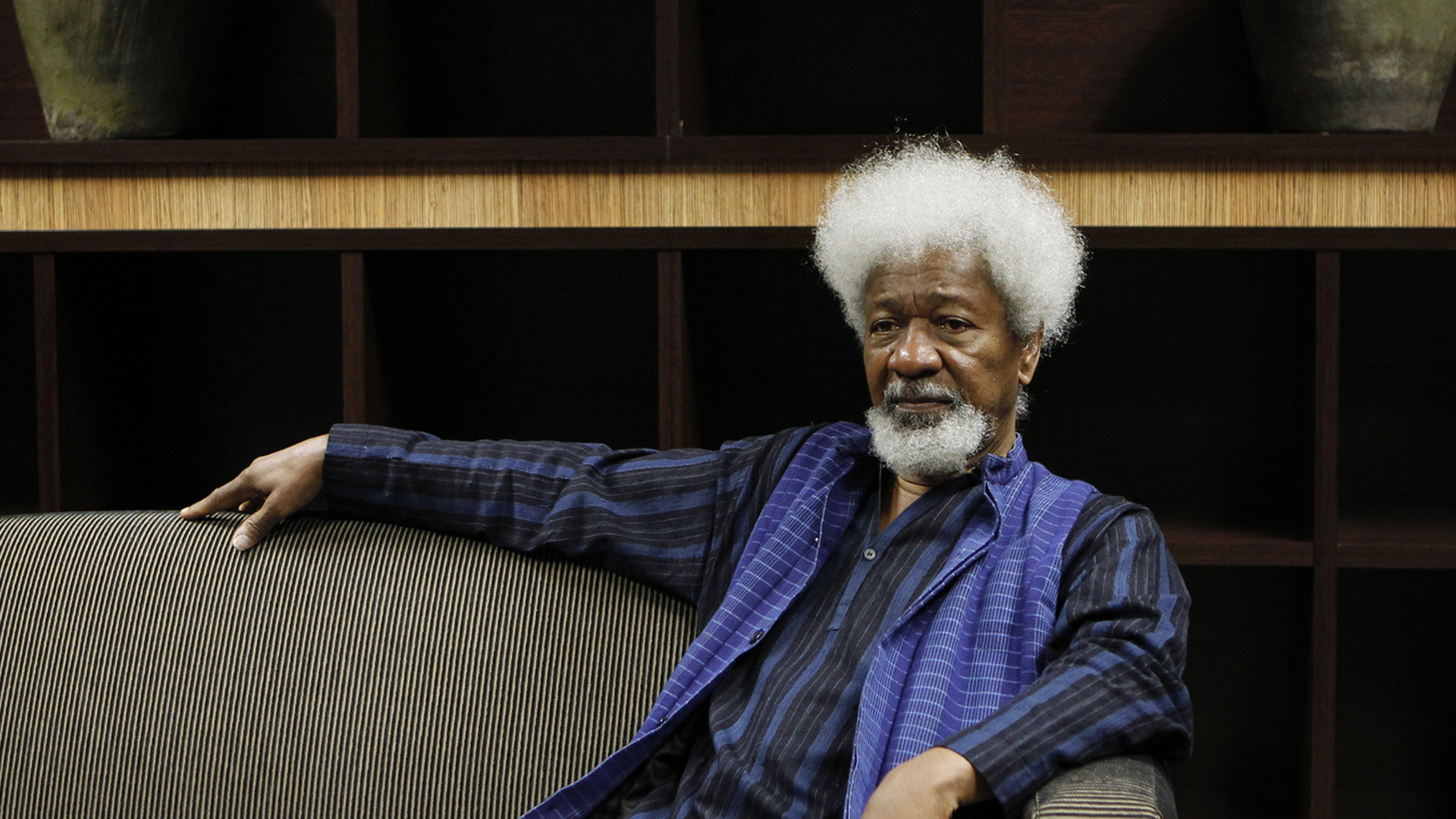

In 1967, under the presidency of American playwright Arthur Miller, PEN appealed to Nigeria on behalf of Wole Soyinka, a playwright marked for immediate execution by the country’s head of state, General Gowon. After a letter from PEN was conveyed by a businessman, Gowon asked if Miller was the same man who had married Marilyn Monroe. When assured that he was, Gowon summarily released his prisoner. In 1986, Soyinka was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

In 1989, when Salman Rushdie, winner of the Booker Prize, published The Satanic Verses, he was forced into hiding when a fatwa was proclaimed, calling for his death. PEN played an instrumental role in the global campaign that called for the withdrawal of the fatwa. Rushdie later became President of PEN America and—in the aftermath of September 11—co-founded PEN World Voices, an international literary festival with a human rights focus held each year in New York. Its aim is to ‘broaden channels of dialogue between the United States and the world’.

The right to speak, write, read and publish freely lies at the heart of global culture. In recent years, PEN has been a leading voice in the call for accountability in the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi inside the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul; and worked hard to secure the freedom of Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo in Myanmar—sentenced to seven years behind bars and recently released after more than five hundred days behind bars.

Thousands of writers all over the world belong to PEN. Among its programs, PEN bestows literary awards; fosters emerging writers isolated from the literary establishment; undertakes prison writing programs; and sponsors translations of works written in obscure or neglected languages. In 2019 Manila will host the PEN International Congress; I have been offered the position of American writer-delegate there. PEN’s historic, vital mission goes on.

The writer David Francis works in the Los Angeles office. He was born in Australia.

First published in RE: issue 15 (2019)