Publication

M&A in the banking sector: Key themes for 2025

Many commentators speculate that 2025 will see a rebound in the overall volume, if not value, of bank deals.

Global | Publication | January, 2016

On 28 January 2016 the European Commission published its proposal for a new Directive that lays down certain minimum standard rules against tax avoidance practices directly affecting the functioning of the internal market (the “Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive”) in line with the project against Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (“BEPS”) of the G20 and the OECD. The proposal aims at combating tax avoidance practices which directly affect the functioning of the internal market. It lays down anti-tax avoidance rules in six specific fields: deductibility of interest, exit taxation, a switch-over clause, a general anti-abuse rule (“GAAR”), controlled foreign company (“CFC”) rules and a framework to tackle hybrid mismatches. The Anti-Abuse Directive contains principle-based rules that need to be implemented into domestic law by Member States. No date has been set for Member States to transpose the measures into national law. The new rules shall serve as the minimum standard, so that Member States remain free to retain or introduce even stricter local anti-avoidance rules. The proposal will require unanimous approval in the Council. Although Member States are committed to implementing the BEPS recommendations, it remains to be seen whether they will wish to agree to the specific form of implementation mandated by the proposed Directive.

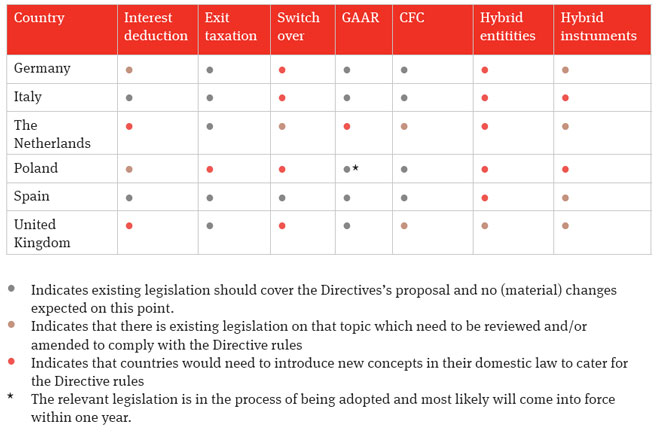

Below we will first summarise the proposed anti-tax avoidance rules by describing the perceived problem detected by the European Commission, the aim of the Directive and the solution found by the EU to tackle the problem. We subsequently provide an overview of the impact of this Directive for selected European countries.

Problem detected: Multinational groups may finance group entities in high-tax jurisdictions through debt and arrange that these companies pay back interest to subsidiaries resident in low-tax jurisdictions.

Aim of the Directive: To introduce a general limit on the amount of interest that the taxpayer is entitled to deduct in a certain tax year.

Solution: To introduce an interest limitation rule, according to which net interest expenses will only be deductible up to 30 percent of the taxpayer’s EBITDA or up to an amount of EUR 1,000,000, whichever is higher. Interest that cannot be deducted (as well as EBITDA that is not fully absorbed under the main rule) can be carried forward to future years. Additional interest may be deductible under an escape rule, if the taxpayer’s equity/total assets ratio is equal to or better than the same ratio of the group to which it belongs (allowing for a 2% variation). However, the latter is subject to very strict conditions, including that the taxpayer can only make payments to associated enterprises up to 10% of the group’s total net interest expense. No further escape rules will be permitted e.g. for taxpayers that do not belong to a group (certain joint ventures or off-balance sheet entities). Financial institutions and insurance companies (“financial undertakings”) are excluded temporarily from the above rule.

Problem detected: Taxpayers may try to reduce their tax bill by moving their tax residence and/or assets incorporating unrealised gains to a low-tax jurisdiction.

Aim of the Directive: To prevent tax base erosion in the Member State of origin when assets which incorporate unrealised underlying gains are transferred, without a change of ownership, out of the taxing jurisdiction of that State, even if to another Member State.

Solution: To introduce an exit tax, levied over the difference between the market value of the transferred asset at the time of the exit less its value for tax purposes, in four specific circumstances: (1) the transfer of assets from head office (“HO”) to permanent establishments (“PE”); (2) the transfer of assets from a PE to a HO or another PE; (3) a transfer of tax residency except for assets that remain effectively connected with a PE; and (4) the transfer of a PE out of a Member State. At the same time taxpayers have the option to defer the exit tax over at least five years and settle through staggered payments when moving within the EU.

Problem detected: Given the difficulties in giving credit relief for taxes paid abroad, States tend increasingly to exempt foreign income from taxation. The negative effect of this approach is that it may encourage untaxed or low-taxed income to enter and circulate within the EU untaxed.

Aim of the Directive: To prevent untaxed or low-taxed income in origin entering and circulating within the EU untaxed.

Solution: To introduce a switch-over clause, where the taxpayer will be subject to regular taxation on certain types of income (instead of being exempt) with a deduction from its tax liability for the tax paid abroad. The relevant sources of income are: (1) profit distributions; (2) proceeds from the disposal of shares; and (3) income from a PE. Non-distributed income is not covered under this clause, but may be caught under the CFC rule discussed below.This switch-over clause shall be introduced if the statutory corporate tax rate of the foreign country is lower than 40% of the statutory corporate tax rate in the Member State of the taxpayer. This switch-over clause will not apply to losses incurred by a PE or losses from the disposal of shares.

Problem detected: Tax planning schemes are very elaborate and tax legislation may not evolve fast enough to include all necessary specific defences to tackle such schemes.

Aim of the Directive: To allow tax authorities the power to deny taxpayers the benefit of abusive tax arrangements despite the absence of a specific anti-tax avoidance rule.

Solution: To introduce a general anti-abuse rule, whereby arrangements that are non-genuine and carried out for the essential purpose of obtaining a tax advantage shall be ignored for the purposes of calculating the corporate tax liability. In such cases, the tax liability shall be calculated by reference to economic substance. Arrangements shall be regarded as genuine to the extent they have been put in place for valid commercial reasons which reflect economic reality.

Problem detected: Taxpayers with controlled subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions may engage in tax planning practices whereby they shift large amounts of profits out of the (highly taxed) parent company towards subsidiaries which are subject to low taxation.

Aim of the Directive: To eradicate the incentive for shifting income out of the Member State of the parent company.

Solution: To introduce CFC rules that allow the re-attribution of non-distributed income of a low-taxed controlled foreign subsidiary to its parent company (adjusted by reference to the arm’s length principle), limited to arrangements which result in the artificial shifting of profits (without economic substance) out of the Member State of the parent company. A CFC is defined as: (1) an entity in which the taxpayer, together with associated enterprises, owns a stake of 50%; (2) being resident in a foreign country that has a statutory corporate tax rate lower than 40% of the statutory corporate tax rate in the Member State of the taxpayer, (3) of which more than 50% of that entity’s income is considered passive; and (4) an entity not listed and regularly traded on a recognised stock exchange. Financial undertakings should be excluded from the scope of the CFC rules where those are tax resident in the EU. Non-EU financial undertakings are not excluded from the proposed rules but other specific exclusions may apply to them.

Problem detected: Hybrid mismatches are the consequence of differences in the legal characterisation of payments (financial instruments) or entities when two legal systems interact.

Aim of the Directive: To tackle hybrid mismatches leading to a double deduction or a deduction of the income in one jurisdiction without its inclusion in the other jurisdiction.

Solution: The legal characterisation given to a hybrid instrument or hybrid entity by the Member State where a payment, expense or loss, as the case may be, originates shall be followed by the other Member State which is involved in the mismatch. These rules should be limited to hybrid mismatches between Member States. Hybrid mismatches between Member States and third countries (including EEA countries) still need to be examined further. These rules should not affect the taxpayer’s obligations to comply with the arm’s length principle or the Member State’s right to adjust a tax liability upwards in accordance with the arm’s length principle, where applicable.

Publication

Many commentators speculate that 2025 will see a rebound in the overall volume, if not value, of bank deals.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025