Publication

Trademark tussles just got spicier: Canada now offers costs awards

Costs awards in trademark opposition proceedings have been long anticipated in Canada.

Author:

Global | Publication | January 2019

Singapore’s recent changes to its insolvency and debt restructuring regime have attracted much interest in the international restructuring world. The intention behind these changes is clear—it is to make Singapore an international centre for debt restructuring.

The starting point of the current changes to the insolvency laws was the appointment of the Insolvency Law Review Committee in December 2010 to review the then existing personal and corporate insolvency regimes. Amongst other things, the committee looked at ways to improve the overall framework for insolvency proceedings and regimes for liquidations, judicial management, schemes of arrangement and receivership. It delivered its report in 2013 with recommendations which included key changes that it felt were needed to modernize Singapore’s insolvency laws and it set out a roadmap for the drafting of detailed and specific statutory provisions.

This was followed up with the establishment of the Committee to Strengthen Singapore as an International Centre for Debt Restructuring. It was tasked with recommending initiatives and legal reforms that should be undertaken to enhance Singapore’s prominence as an international debt restructuring centre. It released its report in 2016.

A three-stage process of legislative changes was planned.

The first stage was the introduction of amendments to the Bankruptcy Act in 2015. Currently, the Bankruptcy Act governs personal insolvency. Corporate insolvency is governed by the Companies Act.

The second stage comprised the introduction of amendments to the corporate insolvency regime in the Companies Act. These amendments were implemented in May 2017. In a little over a year, close to 100 applications were filed in the courts by distressed companies under the new Companies Act provisions.

The third stage will be the introduction of an omnibus insolvency act which will consolidate the corporate and personal insolvency laws into a single statute and introduce further changes as well as include enhancements to some of the amendments introduced in May 2017.

To this end, the Insolvency, Restructuring and Dissolution Bill was passed by Parliament in October this year and it is expected to come into force sometime during the course of 2019.

Two of the main changes made to the Bankruptcy Act in 2015 were:

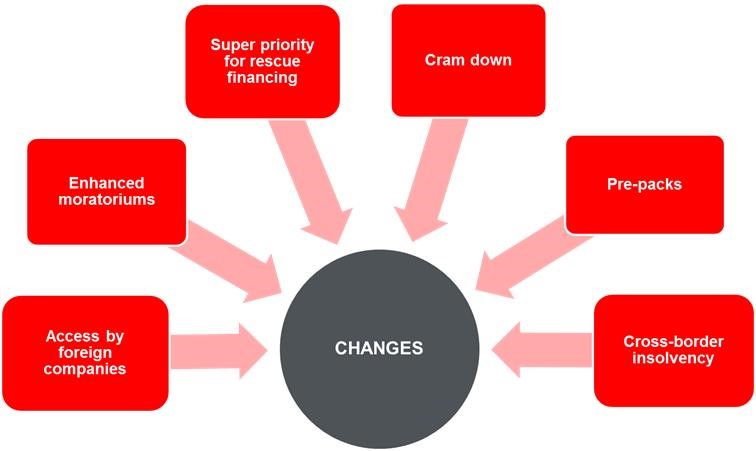

The main changes were to increase and clarify the jurisdiction of the Singapore courts to hear and deal with debt restructuring applications, introduce automatic and enhanced moratoriums in support of such applications, provide for super priority for rescue financing, introduce “cram down” provisions to address the problem of minority dissenting creditor classes in certain situations, allow pre-packaged restructurings, abolish the “ring-fencing” rule under which Singapore liquidators of foreign companies had to utilize assets located in Singapore to first satisfy debts incurred in Singapore and adopt the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency.

Under the previous insolvency regime, only a foreign company which fell within a very narrow definition of “foreign company” could turn to the jurisdiction of the Singapore courts and avail itself to the debt restructuring provisions of the Companies Act. This has changed. A “foreign company” can now make a debt restructuring related application to the Singapore courts if it has “a substantial connection” with Singapore. What constitutes a “substantial connection” includes factors such as the company:

These factors are listed in the Companies Act to give a greater degree of clarity and certainty as to when a foreign company is able to demonstrate the “substantial connection” required for the Singapore courts to assume jurisdiction over its debt restructuring efforts.

Previously, a company seeking a moratorium to protect itself from unilateral creditor actions while it tried to put together a scheme of arrangement could make an application to the court for a moratorium but only if it had already proposed a restructuring proposal to its creditors or, as held by the court in Re Conchubar Aromatics Ltd and other matters [2015] SGHC 322, it had a proposal that was sufficiently detailed as to indicate that there was something definitive that could be put to the creditors shortly and the application for the moratorium was bona fides.

A company can now apply for a moratorium if it had proposed or intends to propose a compromise or arrangement with its creditors and an automatic moratorium of 30 days would “kick-in” upon the filing of the application.

Also, when hearing and granting the moratorium applied for, the court has the power to grant a moratorium with in personam worldwide effect.

Further, the court can grant a moratorium in respect of holding company, ultimate holding company and subsidiary companies (provided certain conditions are satisfied).

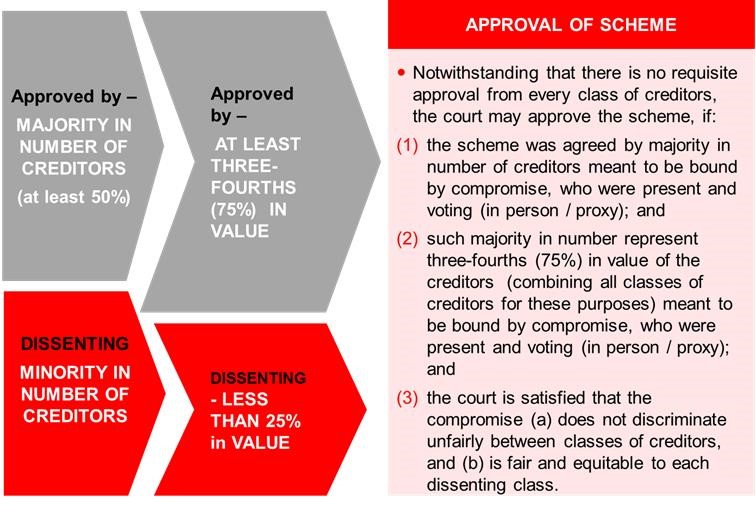

Until the changes introduced in May 2017, any scheme of arrangement needed the approval of every class of creditors amounting to not less than 75% in value and 50% in number in each class. This meant that as long as a class of creditors refused to approve the scheme, even if they represented a small proportion of the company’s total debt, the scheme would be voted down.

Post-May 2017, the court has the power to approve a scheme even if a class of creditors opposes it. The requirements are illustrated below:

The amendments allow priority for rescue financing. Rescue financing is defined as financing that is either:

A company can apply for an order for priority rescue financing when (a) it has made an application for a scheme or for a moratorium or (b) there is a judicial management order in force and the judicial manager makes an application.

In Re Attilan Group Ltd [2018] 3 SLR 898, the court determined that as this amendment was inspired by the super priority status provisions of Chapter 11 of the US Bankruptcy Code, US case-law authorities could be helpful in illuminating how the court should construe the corresponding Singapore Companies Act provision.

The court held that granting super priority should not ordinarily be resorted to; generally, it would only be fair and reasonable to reorder the priorities on winding up and giving the rescue financier the ability to get ahead in the queue for assets in cases where there was some evidence to show that the company could not otherwise have got financing.

The safeguards and protections for creditors, both existing and new rescue financiers, include the following:

Provisions giving the court the power to approve schemes without a creditors’ meeting were introduced. The intention is to allow a fast-tracking of pre-negotiated schemes of arrangement between debtor companies and major creditors. The threshold requirement is that not less than 50% in number and 75% in value of each class of creditors would have approved the scheme had it been put before a meeting of creditors.

To facilitate cross-border insolvency (to promote recognition of and assistance with foreign insolvency proceedings and co-operation and communication between courts), the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency was adopted. This mirrored the approach taken in other key jurisdictions in recent years including the US, UK, the Republic of Korea and Japan.

The new provisions adhere closely to the text of the Model Law. No additional conditions to the recognition of foreign insolvency proceedings in Singapore were imposed.

Separate from legislative amendments, the courts adopted a pro-active or Judge-led approach to managing debt restructuring applications which would be heard by a bench of judges experienced in restructuring work.

Also, Singapore initiated what is called the Judicial Insolvency Network or “JIN”. It is a network of insolvency judges from around the world which aims to encourage communication and cooperation amongst national courts by pulling together best practices in cross-border restructuring and insolvency to facilitate cross-court communication and cooperation.

To date, judges from over 10 jurisdictions have joined the network. These include judges from England and Wales, Delaware and the Southern District of New York, British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, the Federal Court of Australia and New South Wales, Argentina, and Brazil.

Some of the key features of this act are:

Previously, a company could only enter judicial management pursuant to a court order. The new provision allows a company to place itself into judicial management provided its creditors agree and support it doing so.

The rationale behind this new provision is to minimize the expense, formality and delay in a company entering judicial management when there is no objection from creditors. Once a company places itself under judicial management, the process will come under the supervision of the court.

The new act provides that if, in the course of the judicial management or liquidation of a company, it appears that the company has traded wrongfully, then the judicial manager or liquidator of a company, or the Official Receiver or, under certain circumstances a creditor or contributor of the company, can make an application to the court for a declaration that the person(s) responsible for the wrongful trading be made personally liable for the debts or liabilities incurred by the wrongful trading.

The person(s) would have had to know that the company was trading wrongfully or in the case of an officer of the company, ought to have known that the company was trading wrongfully.

Previously, actions to unwind transactions at undervalue or unfair preference transactions or against errant parties in transactions amounting to fraudulent or wrongful transactions were not often pursued because of a lack of financial resources.

Now, judicial managers and liquidators will have the power to assign a portion of the proceeds of such actions to third parties prepared to fund them. This will provide stakeholders with higher recoveries if and when these actions are successful.

The significance of this provision is that with the exception of international arbitration, third party funding for litigation is still considered contrary to public policy in Singapore. Interestingly, in Re Fan Kow Hin [2018] SGHC, the court held that an assignment of a portion of the moneys clawed back in actions to unwind undervalue transactions or unfair preference transactions was not contrary to public policy for being champertous. In any event, this is no longer a live issue because the new statutory provisions explicitly allow for an assignment of some of the proceeds to funders.

New limits on the enforceability of certain types of ipso facto clauses will help a distressed company to restructure by protecting its valuable commercial contracts from being terminated by reason only that the company has embarked on restructuring efforts.

Similar restrictions on ipso facto clauses are found in US, Canadian and Australian insolvency laws and in fact, the new Singapore provision takes its language from the corresponding clause in the Canadian Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act.

To balance the interests of all the parties and stakeholders, certain safeguards have been introduced. Certain categories of contracts are expressly exempted because of the possible disproportionate adverse impact on markets or because they may affect the national interests of Singapore.

A counterparty to a contract that is not exempted may apply to the court for relief on the basis of significant hardship.

Insolvency practitioners will be licensed and only “qualified persons” will be eligible. A “qualified person” is defined as:

The amendments provide for the investigation and disciplining of insolvency practitioners for breaches of conduct. The rationale behind the introduction of this regulatory regime is to improve the standard and accountability of insolvency practitioners.

Those familiar with the insolvency laws of the US, England and Wales, Australia, Hong Kong and Canada will see the conceptual ancestry of many of the changes to the insolvency regime in Singapore. The updating of Singapore’s insolvency legal landscape is still in its early days. Whether it achieves the goal of making Singapore an international centre for debt restructuring remains to be seen but it would be safe to say that the general consensus so far is that it is at the very least a step in the right direction.

Publication

Costs awards in trademark opposition proceedings have been long anticipated in Canada.

Publication

On April 1, after more than a year of consultation, research and consideration, Ontario’s Civil Rules Review (CRR) working group released its proposed reforms to the Rules of Civil Procedure – the rulebook that governs litigation in the province.

Publication

Canada’s 45th general election will take place on April 28. Businesses and non-profits that are considering engaging in the political process during this time must know the law and understand how to navigate the rules and restrictions imposed by the Canada Elections Act (CEA).

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025