Event

2025 Insurathon: Pitch to win £50,000 of investment and pro bono UK legal advice

The Insurathon is a Norton Rose Fulbright event which fosters technological advancements and innovation in the insurance sector, now in its eighth year.

Global | Publication | January 2018

The last couple of years have been notable for the absence of financings of Airbus and Boeing aircraft supported by the European Export Credit Agencies and US Eximbank. Airlines have had to look to other sources of finance for new aircraft in recent years, and the large manufacturers have had to monitor carefully the expected funding sources for some of their pipeline of deliveries.

Providing a solution, the AFIC aircraft non-payment insurance product has been developed by Marsh in cooperation with Boeing and seeks to make use of billions of dollars of risk capital in the insurance market, to support financiers’ exposures to borrowers in the aircraft finance market. The insurers do not provide funding themselves, but they assume the risk of default by providing coverage to lenders, who are expected to rely on the credit of the insurers. Marsh is the exclusive broker for the AFIC product. The current consortium of insurers all have external credit ratings of at least ‘A’ (Standard & Poors).

The basic concept and structure of AFIC is similar in many ways to an ECA financing, with an insurance policy being provided instead of guarantee. Lenders enter into a loan agreement and advance funds to finance an aircraft, in reliance on an insurance policy issued by a consortium of insurers which covers the risk of non-payment by the borrower.

The premium for the insurance is paid in full on the drawdown date and can be financed as part of the loan amount which is covered by the policy, in a similar way to an ECA guarantee premium.

Under the insurance policy, the insurers agree to cover the risk of a default in respect of scheduled payments of principal and interest. After a missed payment, the insurers agree to pay the missed payment (with accrued interest) within a specified time.

Thereafter, there is an assumption that payment defaults will continue so the insurers agree to advance scheduled payments on the correct payment dates to avoid any mismatch of funding arrangements or broken interest periods.

These payments of scheduled principal and interest continue until the earlier to occur of (i) a set period (e.g. 18 months) from the first missed payment, or (ii) the date of the sale of the aircraft – when the insurers will pay the balance of the outstanding principal, with accrued interest, as one final payment. This period is to allow time for an enforcement of security and sale of the aircraft, or (possibly) for defaults to be remedied or debt refinanced.

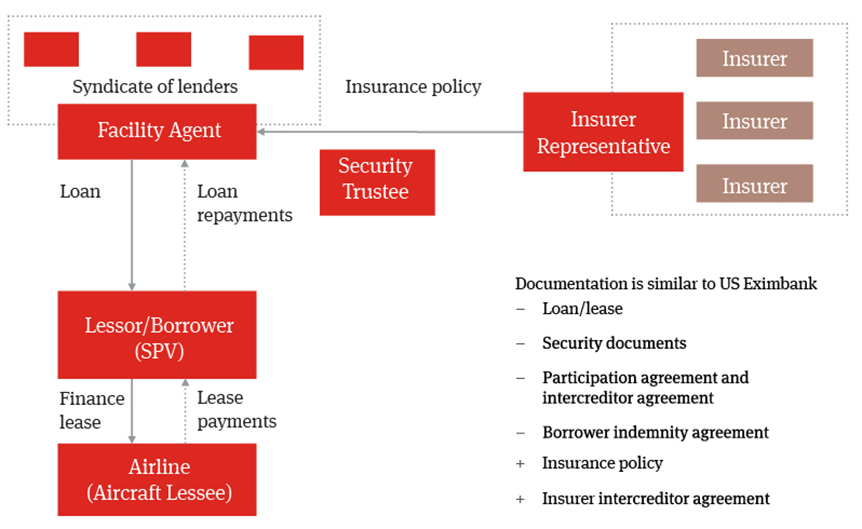

Broadly speaking, the form of transaction documentation for an AFIC financing is similar to the documentation used for a US Eximbank guaranteed financing. A typical structure involves a loan made by the lenders to a bankruptcy-remote Special Purpose Vehicle, with a finance lease from the SPV (as lessor) to the airline or leasing company.

A customary security package is used, including an aircraft mortgage and security assignments, security over the SPV, and warranty and insurance documents. The Security Trustee holds the security for the insurers and for the lenders. The insurers are represented by an Insurer Representative (one of the insurers) who is a party to the transaction documentation, and is entitled to give or withhold consents or waivers much like the role of Eximbank in a US Eximbank transaction. Until there is no exposure under the insurance policy, or amount owing to insurers, the Insurer Representative therefore has the role of an ‘Instructing Group’ entitled to make decisions and to give directions to the Security Trustee.

In addition, the insurance policy is a key document between the insurers and the lenders, and takes the place of the guarantee in an ECA financing. An insurer intercreditor agreement regulates the respective rights and obligations (and voting) between the insurers.

If there is a default, the Facility Agent can claim under the insurance policy. Once the insurers make the payment to the lenders, the insurers will be subrogated to the right of the lenders in respect of that payment, and the insurers become entitled to claim from the borrower and to recover the payment in the ‘waterfall’ on the distribution of any security or sale proceeds.

Although there are many similarities with ECA financing, there are also some key differences which apply to the AFIC structure. These include commercial or intercreditor considerations resulting from the use of multiple corporate insurers, differences between insurance law and guarantee law, the bank capital regulatory analysis which applies to an insurance policy, and the fact that the insurance market is highly regulated.

A key difference is that the insurers, although highly rated, are not sovereign entities. Therefore banks will analyse and account for a transaction not on the basis of sovereign risk, but on the basis of the corporate credit rating of the insurance companies.

In addition, the insurance is provided not by one insurer, but by four insurers on a several basis. Each insurer is liable only for its own share of the liabilities, and there is no joint liability. Banks may therefore need to analyse and account for each portion of the debt on a different basis, taking into account the exposure to each insurer. This is also relevant to the insurer intercreditor agreement. In the event that one insurer fails to pay, the lenders will – in turn – want to be subrogated to the rights of that insurer in the insurer intercreditor agreement, to recover the relevant share of any security proceeds, or to exercise voting rights.

As the insurance is provided on a commercial basis, there are no OECD rules about any level of national content in the aircraft, nor about the invoice price applicable to an aircraft. Similarly, there is no “home country rule” preventing leasing to countries where large aircraft are manufactured.

There are aspects of insurance law which are different from the law that applies to guarantees; however, many provisions of insurance law can be varied or dealt with by contract. For example, there is the requirement that the party which is ‘insured’ must have an ‘insurable interest’. In a syndicated transaction, a Facility Agent may not hold the loan itself, or a lender may have granted a participation to another person as part of a risk transfer. In both these cases, policy wording can be included to ensure that the insurers will not be able to deny coverage as a result of a lack of insurable interest.

Another concept under insurance law is the basic duty to disclose relevant information relating to the insured risk, breach of which can give rise to a defence for insurers if the insured risk materialises. Again, wording can be included in the insurance policy in order to limit this duty, specifying what information has been disclosed and specifying which individuals are in the ‘deal team’ whose knowledge is relevant, and excluding defences which might otherwise be available to insurers.

Generally, although the principles of insurance law are protective of insurers, these provisions can be addressed by express drafting in order to end up with an insurance policy which is “as good as” a guarantee. Nevertheless, the document must be an insurance policy, in line with the requirements applicable to the insurers who issue it.

Banks entering into a finance transaction in reliance on the insurance policy, and the creditworthiness of the insurers, will also want to ensure that they can receive the desired regulatory capital relief in order to benefit from the structure, or to price their transaction accordingly.

For CRD IV purposes, applicable to European banks, financiers will therefore want to check or receive a legal opinion that the insurance policy is akin to a guarantee, in the context of the overall structure of the transaction. Of course, it is the lending banks (rather than the Facility Agent) who need to receive the capital relief. Amongst other things, the protection needs to be ‘direct’, which means that mechanisms need to be included to enable individual lenders to initiate a claim process in the event that the Facility Agent omits to do so, and the structure needs to provide for the lenders to have the right to receive the proceeds. It is also necessary to check that no circumstances outside the control of the lenders can invalidate the protection.

Finally, it is important to understand that the insurance market is highly regulated. There are many different regulations relating to the selling or provision of insurance, which usually depend on the identity and jurisdiction of the insured. An insurer may have to hold certain licences, and comply with certain regulatory requirements, to provide insurance to a customer in one country, yet may need to hold different licences and comply with different requirements to write insurance for a customer in another country. Insurers, much like banks, may act through many different group companies.

If the lenders are the ‘insured’, then the insurers will need to carry out their own regulatory analysis on each lender. This may affect the process of syndication by lenders, if lenders seek to transfer a loan interest to a new party. The payment of premium by the ‘insured’ may need to be analysed for tax purposes. Details such as these need to be considered at the documentation stage of a transaction, and participations or other arrangements may need to be used by lenders in order to give them maximum flexibility. Other variations on the basic AFIC transaction structure may be able to be used in order to allow greater flexibility, or to avoid the lenders being treated as the ‘insured’ in the regulatory analysis by the insurers. These structures need to balance both the insurers’ regulatory needs with the banks’ own regulatory capital requirements.

The development of the AFIC product marks a positive step in broadening the availability of financing and credit support for aircraft deliveries, and Marsh and Boeing should be congratulated for their work. By all accounts, the AFIC insurers intend to continue to grow their portfolio of aircraft and airline customers and do not see the role of commercial insurance as being merely temporary. More generally, the interest of the insurance market in the world of aircraft finance, and the process of education and research which has been undertaken in respect of the aviation industry, show that aircraft investors and manufacturers may have a yet broader range of funding sources to call on in the years ahead.

Event

The Insurathon is a Norton Rose Fulbright event which fosters technological advancements and innovation in the insurance sector, now in its eighth year.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025