Event

2025 Insurathon: Pitch to win £50,000 of investment and pro bono UK legal advice

The Insurathon is a Norton Rose Fulbright event which fosters technological advancements and innovation in the insurance sector, now in its eighth year.

Global | Publication | August 2018

This summer the media reported that the European market for non-performing loans (NPLs) was becoming more active, with Italy and Spain accounting for most of the deals. According to the European Central Bank’s (ECB) semi-annual financial stability review, the total gross book value of NPL portfolios traded in the Eurozone reached €66 billion in Q4 2017, its highest since the data series began in 2015. The bulk of this figure came from Italy and Spain where several significant portfolios accounted for the majority of the total. The ECB has also noticed that transactions have begun to emerge in Greece, and Cyprus has seen its first NPL sales. However, the ECB has also seen a decline in activity in active markets such as Ireland as the number of NPLs decrease.

In this banking reform updater we look at the regulatory response to NPLs.

An NPL is a loan where the borrower is not making repayments in accordance with the contractual obligations. NPLs are impaired when the amount expected to be repaid falls below the contracted value carried on a bank’s balance sheet. When this occurs loan loss provisions (LLPs) are made on the balance sheet, this accounting deduction amounts to the difference between the money borrowers from banks have agreed to repay, and banks’ most current estimate of the amount they will actually receive.

Until recently, the specific criteria for loans to be classed either as ‘impaired’ or as ‘non-performing’ varied across jurisdictions and firms, and within firms. This meant that the threshold for impairment and provisions were also different. This made it difficult to make any meaningful comparison of the quality of different banks’ assets, it also made it hard for third parties to make decisions regarding whether bank recapitalisation and recovery could occur.

The ECB has been looking at NPLs for some time. Its focus on the issue began a couple of years ago with the 2014 comprehensive assessment comprising of an asset quality review and stress test. Following this assessment, the ECB intensified its supervisory work on NPLs, creating a high-level group which was mandated to develop a consistent supervisory approach to NPLs. The high level group identified a number of best practices which subsequently led to the March 2017 ECB guidance to banks on NPLs (which has since been supplemented by an addendum in March 2018). The guidance follows the life cycle of NPL management starting with the ECB’s supervisory expectations on NPL strategies, governance and operations. Following that, the guidance covers forbearance treatments, NPL recognition, NPL provisioning, write off and collateral valuations. The guidance is non-binding in nature but banks supervised by the ECB are expected to be able to explain and substantiate any deviations from it upon supervisory request (in other words it’s on a comply or explain basis).

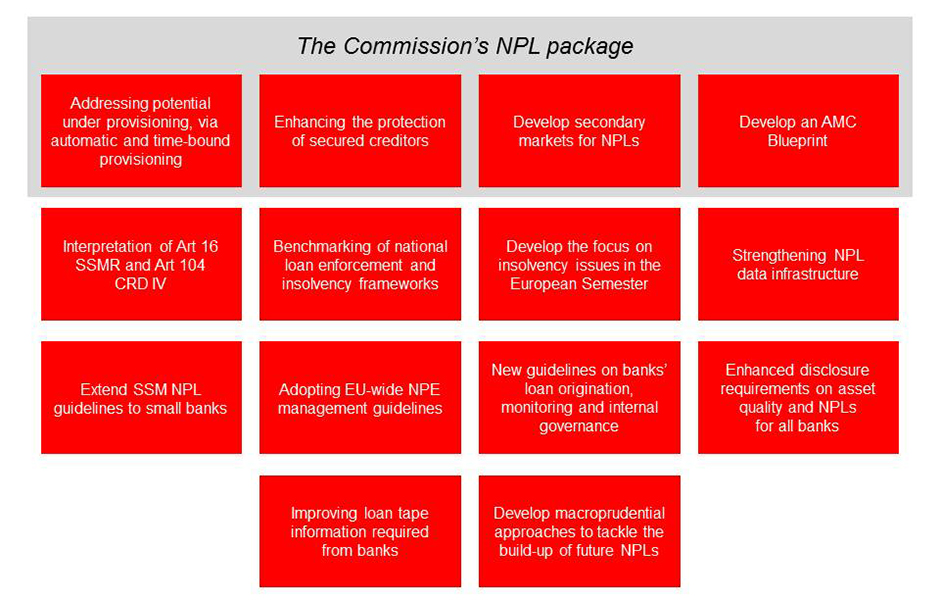

Following the publication of the ECB guidance in March 2017, the Council of the EU published a couple of months later in July 2017 conclusions on an Action Plan to tackle NPLs in Europe. The Action Plan stressed that a comprehensive approach was needed involving a mix of policy actions at both the EU and national level. Such policy action would cover four key areas: (i) supervision; (ii) structural reforms of insolvency and debt recovery frameworks; (iii) development of secondary markets for distressed assets; and (iv) restructuring of the banking system. The European Banking Authority (EBA) would play an important role in the development of the policy action.

The European Commission published its first progress report on the Action Plan on NPLs in January 2018. A second progress report shortly followed in March 2018.The second progress report coincided with the publication of proposals for a Directive and a Regulation which would

Essentially the draft Directive is intended to prevent excessive future build-up of NPLs on banks’ balance sheets. It does this in two ways. First, it encourages the development of an EU-wide secondary market for NPLs, by setting common standards for the “proper conduct and supervision” of credit servicing companies, specialist firms with the “necessary risk appetite and expertise” employed by banks to seek repayment of non-performing consumer and commercial loans. Second, by requiring each EU Member State to establish an AECE which is intended to be a faster way for banks to salvage bad business loans by recovering the collateral against which they are secured rather than through existing insolvency and debt recovery legislation.

In relation to the development of the secondary market for NPLs, the draft Directive creates a common set of rules that third party credit servicers need to abide by in order to operate. Such rules include

Importantly, an authorised credit servicing company would be able to passport its services in any EU Member State. Supervision of the authorised credit servicing company would be the responsibility of the home Member State authority although authorities in host Member States could conduct checks, inspections and investigations in respect of credit servicing activities in their territory. The draft Directive does not provide for an equivalence regime for non-EU credit servicing companies.

Credit purchasing is another important component of the draft Directive setting out minimum disclosure requirements by the bank towards the prospective buyer of a loan agreement, as well as requiring the sale to be notified to the regulatory authority. Non-EU credit purchasers will need to appoint a designated representative in the EU before they can purchase a credit agreement involving an EU-based borrower.

In terms of accelerated collateral recovery, the draft Directive requires Member States to establish, in law, a “more efficient” method for banks and credit purchasers to recover money from secured loans to business borrowers without recourse to legal action in court. Recovery of collateral under the AECE will take the form of a public auction, private sale or outright appropriation of the asset by the creditor. The AECE will only be available when agreed on in advance by means of a loan agreement between the lender and the borrower, and could not be used in relation to secured consumer credit agreements, such as residential mortgages.

To ensure fair treatment, the draft Directive requires the creditor to have the assets independently valuated to determine the appropriate reserve price for auction or private sale (or its value to the bank in case of appropriation). The valuer needs to be appointed by common consent of both the lender and the borrower, and the collateral could only exceptionally be sold for less than the reserve price (and never for less than 80 per cent of the estimated value). Any positive difference between the selling price and the outstanding debt would revert to the borrower.

The draft Regulation amending the CRR would create a "prudential backstop", whereby banks would be required to have sufficient liquid funds to cover the incurred and expected losses on new loans once such loans become non-performing, up to a common minimum level (the minimum coverage requirement), comprised of provisions recognised by the relevant accounting framework. Where the bank does not meet the minimum coverage requirement, the prudential backstop would apply: a bank would have to deduct the difference between the level of the actual coverage and the minimum coverage from its statutory Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) prudential capital.

Specifically

Arguably, not very far (at least publicly). Both EU legislative proposals are now undergoing review by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. The European Parliament procedure file for the draft Directive states that a vote is scheduled in committee on December 3, 2018.

The market reaction to the draft legislation has generally been positive. Like any other draft piece of EU legislation there have been comments and queries regarding certain aspects including the definitions used for “credit agreement” and “credit servicer”, and the overall application of the draft Directive which, if too broadly applied, would require, according to one trade body, significant changes to existing market practice.

The Commission published alongside the legislative proposals mentioned above a staff working document setting out non-binding technical guidance (a so-called blueprint) for how national asset management companies (AMCs) can be set up. Historically AMCs have removed non-performing assets from banks’ balance sheets. AMCs have also acted as a catalyst to develop secondary markets for distressed debt. They can be private or (partly) publicly funded without State aid, if the State can be considered to act as any other economic agent. The blueprint contains common principles including the relevant asset perimeter, the participation perimeter, considerations on the asset-size threshold, asset valuation rules, the appropriate capital structure and the governance and operations of the asset management company. It also describes certain alternative impaired asset relief measures that do not constitute State aid.

In October 2017, the Commission provided an interpretation in the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) review report clarifying that EU legislation, in particular Article 16(2)(d) of the EU Regulation on the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSMR) and Article 104(1)(d) CRD IV, provides the EBA with powers to influence a bank’s provisioning policy with respect to NPLs within the limits of the applicable accounting framework and to apply any necessary adjustments to own funds on a case-by-case basis (see footnote eight of the European Commission’s report on the SSM (dated October 11, 2017).

The EBA’s activity on NPLs is another important component of the regulatory response to NPLs. There have so far been four notable EBA papers, being

The EBA also intends to issue for consultation guidelines on banks’ loan origination monitoring and internal governance in H1 2019.

The EBA’s proposal to apply chapters four and five of the EBA NPL Guidelines to those credit institutions with an NPL ratio in excess of 5 per cent is likely to significantly increase the administrative and cost burden for banks of those countries that have suffered most from non-performance in their lending books, particularly if third party annual reviews become embedded as part of the new framework.

In December 2016 the EBA published guidelines on disclosure requirements under Part eight of the CRR. The guidelines included a template on non-performing and forborne exposures, requesting institutions to disclose information on the gross carrying amount and accumulated impairments of performing, non-performing and forborne exposures, and on the collaterals and guarantees received. The template has to be filled in by global systemically important institutions and other systemically important institutions. The EBA is broadening the scope of application of the template on non-performing and forborne exposures to all institutions by the end of 2018.

The EBA has published standardised NPL data templates (also known as loan tapes) to allow banks to supply comparable and standardised data on NPLs to investors and other stakeholders. Whilst not a supervisory reporting requirement they are designed to act as a market standard, to be used by banks on a voluntary basis for NPL transactions, and to form the foundation for NPL secondary markets initiatives.

At least publicly, there appears to have been little movement on this following the ECB’s Financial Stability Review in November 2017 which featured a discussion on overcoming NPL market failures with transaction platforms. The EBA affirmed in its 2017 Annual Report (published June 2018), its commitment to enhancing in 2018 the data infrastructure of secondary markets on NPLs.

The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) has a dedicated work stream on macro-prudential approaches to prevent the emergence of system-wide NPL problems. A final report is scheduled to be presented at the ESRB’s general board meeting on September 27, 2018.

The draft Directive on credit servicers, credit purchasers and the recovery of collateral is due to take effect on January 1, 2021. The draft Regulation amending the CRR comes into force on the day following its publication in the Official Journal of the EU (which we assume will be the same date as the coming into force of the draft Directive). If a hard Brexit occurs and the UK leaves the EU on March 29, 2019 without a deal then it is possible that the UK will not implement these legislative measures into its domestic regime. If the EU and UK finalise the Withdrawal Agreement then both pieces of EU legislation come into force outside the transitional period and therefore it is possible in this scenario that the UK will not implement these measures. However, given the objectives that these legislative measures seek to address it is hard to see the UK not implementing them.

The regulatory response to NPLs is somewhat of a jig-saw which requires piecing together different measures being implemented by the ECB, the Commission and the EBA.

Arguably, the EU regulatory response may be beginning to bear fruits.

In August 2018, it was reported that the Bank of Cyprus had struck a deal to sell a €2.7 billion NPL portfolio to a US private equity firm. The transaction is the first NPL disposal by the central bank, and comes as a positive move forward for one of the highest-profile casualties of the global financial crisis. Similarly, figures published by the Central Bank of Ireland show that between Q3 2014, and Q4 2017, the central bank reduced its NPL portfolio from €84.7 billion to roughly €30 billion. In the third quarter of 2017, bad debt across the euro area amounted to €759 billion the ECB recalled, down from €950 billion at the start of 2016. While the EU-wide average level of NPLs is 4.4 percent, different countries have highly variable stocks, from 46.7 percent in Greece or 12.1 percent in Italy to 2.1 percent in Germany. The Commission proposals would give banks two years to set aside cash to cover existing NPLs not backed by collateral, and eight to provide for those with guarantees.

Event

The Insurathon is a Norton Rose Fulbright event which fosters technological advancements and innovation in the insurance sector, now in its eighth year.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025