Event

2025 Insurathon: Pitch to win £50,000 of investment and pro bono UK legal advice

The Insurathon is a Norton Rose Fulbright event which fosters technological advancements and innovation in the insurance sector, now in its eighth year.

Since our last update, progress on addressing climate change has slowed as the world grapples with responding to the devastating COVID-19 pandemic.1 As recently noted by António Guterres, the UN Secretary General “the world is way off track” in taking action consistent with the targets in the Paris Agreement.2

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on climate change litigation are not yet certain—it remains to be seen whether there will be fewer new filings, a slower pace of determination of matters, or a shift in the types of cases or grounds argued, such as tying threats to human health to the impacts of climate change.

So far, there continues to be a strong appetite for climate change litigation. The use of litigation as a form of protest by climate activist groups, a focus on human rights violations in the context of climate change, and pressuring of fossil fuel companies to develop climate strategies continue to emerge as important trends in litigation strategies and in the types of argument being adopted by litigants.3

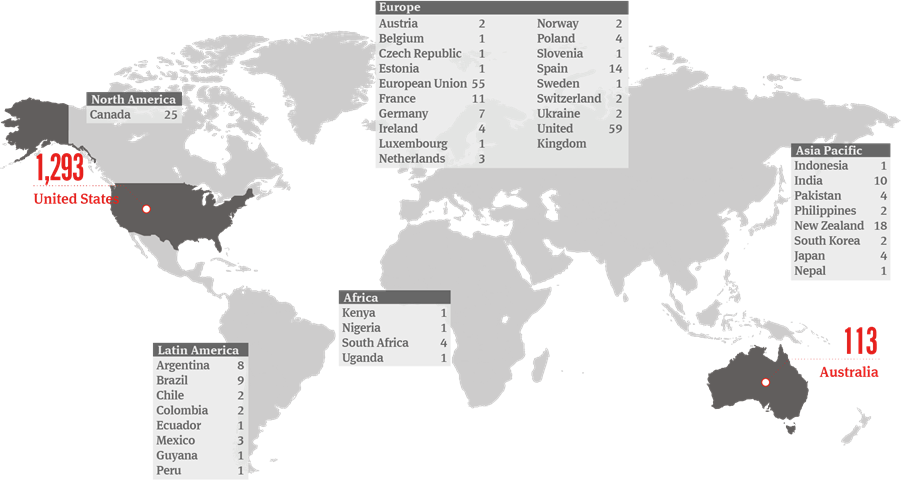

As at November 2020, the total number of climate change cases filed to date has reached over 1,650,4 up from about 1,444 as at February this year. Cases have now been filed in all six continents and in at least 36 countries, in addition to cases brought in regional or international courts or commissions. The vast majority of these cases continue to be commenced in the United States (US), followed by Australia, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Canada, New Zealand, and Spain.

This legal update considers key developments and cases since February 2020.

The cases are divided into the following categories:

Since the landmark Urgenda case (see our previous updates on this litigation here, here and here), human rights-related cases are emerging as a dominant climate litigation strategy, with the Grantham Institute labelling this trend as the “human rights turn” in climate litigation.5

In February 2020, two houses of the Wet’suwet’en, a First Nations people who live in the Central Interior of British Columbia, filed a complaint against the Government of Canada for failing to follow through on the commitments it had made to reduce Canada’s GHG emissions, including most recently the Paris Agreement. The plaintiffs have brought their claim under various provisions of Canada’s Constitution and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, alleging that they have faced mounting issues as a result of climate change, including insect infestations and wildfires in their forests and declining numbers of forest food animals and salmon in their fishery.

The plaintiffs are seeking a court order declaring Canada’s environmental assessment statutes that allow for high GHG emissions to be unconstitutional, and that, if Canada is not able to meet its obligations under the Paris Agreement (or finds climate change to be a national emergency), it may withdraw approval for high emission projects. They are also seeking an order that would require Canada to complete an annual, independent account of its cumulative GHG emissions to show whether it is meeting its Paris Agreement commitments. The proceeding is pending.

In March 2020, 30 South Korean youths filed a complaint alleging that South Korea’s Framework Act on Low Carbon, Green Growth (Framework) is unconstitutional as its commitment to reduce annual nationwide GHG emissions to 536 million tonnes by 2030 is insufficient to keep global warming below 2°C as decided under the Paris Agreement.

The complainants argue the Framework breaches constitutional human rights by risking present and future loss of environment, human conditions, health and life due to the ongoing increase of GHG emissions temperature. The petitioners are asking the Court to declare the Framework unconstitutional and order the South Korean Government to correct the unconstitutional situation. This case is the first of its kind in East Asia.

In May 2020, various parties led by Youth Verdict Ltd, which represents Australian Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people, commenced proceedings against the approvals granted for Waratah Coal’s Galilee Coal Project in the Queensland Land Court.

The Galilee Coal Project is estimated to be more than four times the size of Adani’s Carmichael Coal Mine. The objectors rely on the Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld) to argue that the mine is unlawful because it breaches human rights by inciting climate change that will risk the future, life, and culture of Queenslanders. The human rights alleged to be breached include the right to life, protection of children, and cultural rights of Aboriginal and Torre Strait Islander Peoples.

Waratah Coal tried to strike out the objections, arguing that the Court did not have jurisdiction to deal with the matter and the objectors did not have standing because they were corporate entities and only individuals possess human rights. On 7 August 2020, the Queensland Land Court dismissed Waratah Coal’s strike out application but the Court is yet to decide on the substantive application.

We will keep a watching brief on whether similar cases will be brought under other State based human rights legislation such as the Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT) and the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic).

In October 2019, a lawsuit was filed with the Federal Court of Canada on behalf of 15 youth plaintiffs against the Canadian government. The plaintiffs’ statement of claim alleged that the Canadian government had failed to protect the plaintiffs’ human rights by not taking adequate action to address climate change. In particular, the plaintiffs alleged that climate change is impacting their right to life, liberty, security of the person and their right to equal opportunity under the law. The lawsuit is based on sections 7 and 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, as well as the Public Trust Doctrine. The plaintiffs have sought declaratory relief as well as an order that requires the Canadian government to develop and implement an enforceable climate recovery plan.

In October 2020, the Federal Court of Canada made a pre-trial motion to strike out the plaintiffs’ statement of claim without leave to amend, on the basis that the statement of claim did not include a reasonable cause of action. The Court also held that the claims regarding the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms were not justiciable, and that whilst the Public Trust Doctrine was justiciable, a reasonable cause of action was not disclosed.6

The plaintiffs have appealed the decision to the Federal Court of Appeal alleging that the Federal Court of Canada erred in making the motion.7

In September 2020, 6 Portuguese youths filed a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights against 33 countries including the Member States of the European Union, Norway, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine and the United Kingdom.

The complaint outlines how the 6 Portuguese youths face risks to their lives and wellbeing due to climate change, stating that climate change is causing heatwaves in Portugal to occur more frequently which has associated consequences. The applicants allege that by failing to take sufficient climate action, the States have breached Articles 2 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which establish the right to life and the right to family and private life.

The applicants also allege that the States have discriminated against youth, breaching Article 14 of the ECHR, as climate change will impact youth more than older generations. They state that “[t]here is no objective and reasonable justification for shifting the burden of climate change onto younger generations by adopting inadequate mitigation measures”. The applicants seek an order requiring the States to take more ambitious climate action.

In November 2020, the Court accepted the application and communicated it to the States. The States have until the end of February 2021 to respond.

The Do-Hyun Kim, Lho’imggin and Youth Verdict cases reflect a growing movement by individuals who have been disproportionately impacted by climate change to rely upon domestic constitutional or human rights laws and international conventions in an attempt to hold states accountable.

However, with respect to domestic claims, the La Rose decision reminds us that success in such claims are jurisdictionally specific and will depend on the extent to which the judiciary is willing to accept that it is an appropriate forum to address issues associated with climate change.

Private law claims have, to date, largely been unsuccessful in the US.8 As compared to governments’ duties to protect its citizens (as discussed above), the obligations of a corporation under private law is not as well defined.

In March 2020, the High Court of New Zealand permitted the plaintiff, who brought legal proceedings against 7 defendants that operate greenhouse gas emitting facilities, to proceed to trial. The plaintiff originally sought to hold the defendants liable for public nuisance, negligence and breach of a duty to stop contributing to climate change.

The plaintiff’s claim in public nuisance was rejected, as the Court found that the damage claimed was not particular to the plaintiff, and that the damage was not a direct result of the defendants' activities. The plaintiff’s negligence claim also failed. The Court found that the damage claimed was not reasonably foreseeable, and the relationship between the defendants and the plaintiff was not sufficiently proximate to give rise to the relevant duty of care.

In relation to the plaintiff’s claim that the defendants breached a new tortious duty of care to cease contributing to climate change, the Court noted that there may be “significant hurdles” in persuading the Court that the duty should be recognised. However, the Court was reluctant to conclude that “the recognition of a new tortious duty which makes corporates responsible to the public for their emissions, is untenable”. It was ultimately determined that the issues should be explored at trial.9

It remains to be seen whether these types of claim brought under tort law will ultimately be successful or whether there may be a move towards the use of human rights-related claims. As we noted in our last update, the Shell case has sought to extend the principles from the Urgenda litigation to private companies, including by arguing that a private company has a duty of care under Dutch law and human rights obligations. The Fonterra case shows that there is appetite for arguing these types of novel claims and courts may be receptive to holding corporates to account for their contribution to climate change.

These disputes typically involve claims against companies for misleading consumers or investors on the impact of the fossil fuel products that they have marketed and sold, and the climate change-driven risks to their businesses.

At least 7 new suits against carbon majors have been commenced in state courts in the US since our last update, including Minnesota and District of Columbia in June, followed by Hoboken, Charleston, Delaware and Connecticut in September. This brings the total number of lawsuits filed across the US against carbon majors since 2017 to over 30. With the defendants being unsuccessful in transferring previous cases to the Federal Court, the suits are likely to continue to be filed in state courts. We have summarised a couple of these new cases below.

In June 2020, the Attorney General for the State of Minnesota filed a lawsuit against American Petroleum Institute, ExxonMobil, Koch Industries and Flint Hills Resources on the basis of internal documents dating back to the 1970s and 1980s which allegedly confirm that the companies “well understood the devastating effects that their products would cause to the climate”.

The Attorney General alleges, amongst other things, that the defendants have profited from “avoiding the consequences and costs of dealing with global warming” and that they deliberately undermined “the science of climate change, purposefully downplaying the role that the purchase and consumption of their products played in causing climate change”.

The lawsuit includes claims for fraud, failure to warn, and multiple separate violations of Minnesota Statutes that prohibit consumer fraud, deceptive trade practices and false statements in advertising. The Attorney General is seeking damages for alleged harms suffered by Minnesotans and orders that the companies fund a corrective public education campaign on the issue of climate change.

The case is currently the subject of jurisdictional arguments as to whether it should be heard in the Federal Court.

In June 2020, the Attorney General for the District of Columbia filed a complaint against Exxon Mobil, BP, Chevron and Shell alleging that they have “systematically and intentionally misled consumers in Washington DC… about the central role their products play in causing climate change”.

The Attorney General claims that the defendants have breached the Consumer Protection Procedures Act. The complaint states that the defendants have deceived consumers in Washington DC on the impacts of climate change in order to protect profits. The Attorney General alleges further that as consensus grew within the scientific community around the relationship between fossil fuels and climate change, the defendants exaggerated their commitments to reducing reliance on fossil fuels and concealing their products harm.

The Attorney General is seeking an order that the defendants cease the alleged’ disinformation campaigns’, provide financial relief for consumers of DC and pay civil penalties. Exxon Mobil have responded to the compliant on behalf of all defendants seeking to move the proceedings to the Federal Court, alleging that the suit aims to limit fossil fuel use, and not address consumer fraud, and therefore is a Federal issue. The outcome of the challenge is pending.

In September 2020, the Delaware Attorney General filed a lawsuit in the Superior Court of Delaware against 31 fossil fuel companies as well as the American Petroleum Institute. The complaint alleges that the named companies have known the climate change impacts of fossil fuels, and seeks financial compensation under the Consumer Fraud Act. In addition to past deceit, the complaint is also focussed on the current practices of these companies, including ongoing “Greenwashing Campaigns.”

A second cause of action is trespass, by causing “floodwaters, extreme precipitation, saltwater encroachment, and other materials to enter the State’s real property” as a result of the use of the defendants’ fossil fuel products. This focus on flooding is of particular relevance to Delaware, which has the lowest average elevation of the United States and will, according to the complaint, cause the State to incur substantial costs to prevent and rectify the damage of rising sea levels.

The case is currently the subject of jurisdictional arguments as to whether it should be heard in the Federal or State Court.

The new US cases against carbon majors build on previous cases, including the unsuccessful New York case and ongoing Massachusetts case summarised in our last update. However, the claims appear to have moved away from alleging that companies misled investors, towards alleging that they misled consumers and that the companies acted together to violate consumer fraud legislation. Suits are also generally being brought against multiple companies.10 Further, beginning with Minnesota, the cases have also begun to include the American Petroleum Institute as a defendant. The trend of suits is expected to continue.

Companies, shareholders and consumers are increasingly accepting that corporate action on climate change is not necessarily mutually exclusive with acting in shareholders’ best interests. Regardless of any formal disclosure requirements, corporations around the world are becoming more aware that the physical and transitional risks of climate change pose a very real threat to their current business models.

The cases below demonstrate that shareholders, individuals and regulatory bodies are often willing to commence proceedings where corporations are perceived to have failed to take meaningful action on climate change or have misrepresented their actions.

In January 2020, Friends of the Earth Australia along with three individuals (who had been affected by the Australian bushfire crisis) filed a complaint with the Australian National Contact Point (ANCP) of the OECD against ANZ. The complaint alleges that ANZ has not adhered to the standards of the OECD Guidelines relating to due diligence, disclosure, environment, and consumer interests. See our previous update for a summary of the complaint.

In November 2020, ANZ published its updated climate change policy statement supporting the Paris Agreement’s goal of transitioning to net zero emissions by 2050, and acknowledging that some of its stakeholders view financing of fossil fuel industries as in conflict with ANZ’s stated position of the need to reduce emissions. The statement contains several commitments including improving transparency to show how ANZ’s financing decisions support the achievement of Paris Agreement goals and further reducing the carbon intensity of their electricity generation lending portfolio by only directly financing low carbon gas and renewable projects by 2030.

Also in November, the ANCP published its initial assessment, accepting that the issues raised in the complaint surrounding disclosure, target-setting and scenario analysis merit further assessment and offering ‘good offices’ to the parties for discussion on those matters. The next phase of the complaint process involves consultation with the parties and may take up to a year. We expect that during this period the ANCP and notifiers will closely examine the measures identified in ANZ’s updated climate change policy statement.

In July 2018, Mark McVeigh commenced proceedings against REST, one of Australia’s largest superannuation funds with total assets over A$50 billion and around 2 million members. Mr McVeigh’s claim alleged that REST failed to adequately disclose its strategy to manage climate change risks, breached its statutory disclosure requirements, and breached its fiduciary duties by failing to adequately consider the risks of climate change in managing investments. See our previous updates here and here for more background on the case.

In November 2020, on the morning of the trial, the parties settled the proceedings, subject to REST publicly announcing a number of commitments regarding its handling of climate change risk. REST’s public statement significantly acknowledges that climate change is a material, direct and current financial risk to the superannuation fund. It also identifies 9 initiatives which include that REST commits to enhancing its consideration of climate change risks when setting its investment strategy and asset allocation positions, conducting due diligence and monitoring of investment managers and their approach to climate risk, publicly disclosing the fund’s portfolio holdings, reporting outcomes on its climate change-related progress and actions, and implementing a long-term objective to achieve a net zero carbon footprint for the fund by 2050.11

Although the REST case settled, meaning that its undertakings are not enforceable in court and it does not set legal precedent, companies and the members of the public are likely to monitor whether REST’s undertakings are implemented. It has also shown the public that individuals can take actions which lead to positive outcomes, even if litigation does not proceed to trial. Given that REST is one of Australia’s largest super funds, we expect the position that it has taken in settling the proceedings may influence other funds,12 both in Australia and internationally, to review their processes for handling climate change risk in order to prevent the risk of attracting similar public interest litigation.

The progression of the ANZ complaint is also likely to be closely watched by the financial and investment communities within Australia and more broadly.

Many jurisdictions have long incorporated obligations relating to ecological sustainable development in their planning controls. Some jurisdictions have laws which require consideration of GHG emissions, or adaptation to and mitigation of climate change specifically in the development of policy or approval of projects. This provides scope for claimants to push for the widest possible interpretation of such obligations so as to address the contributions which individual projects or policies may have on climate change.

In February 2020, the Court of Appeal of England and Wales unanimously ruled that the Airports National Policy Statement (NPS), which provided for the construction of a third runway at Heathrow Airport, was invalid and its designation as a NPS was unlawful on several grounds including notably that it failed to take into account the UK Government’s commitment to the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Under the Planning Act 2008 (UK), the Secretary of State was required to explain how the national policy “takes account of Government policy relating to the mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change”. At the time of designation of the NPS in 2018, the UK had legislated a 2050 target of achieving at least an 80% reduction in its GHG emissions from 1990 levels under the Climate Change Act 2008 (UK). The Secretary took this target into account but, on legal advice, chose not to take the Paris Agreement into account at all.

The Court determined that the UK government’s commitment to the Paris Agreement was part of “Government policy” and was required to be taken into account. See our previous legal updates for more detail on that case here and here.

In May 2020, the Supreme Court granted Heathrow Airport Limited and Arora Holdings Limited permission to appeal the Court of Appeal’s ruling. Among other things, the appellants argue that treating the Paris Agreement as "government policy" for the purposes of the Planning Act and as a mandatory consideration runs contrary to the common law principles of a “dualist system”. Accordingly, the appellants argue that the case raises issues of general public importance warranting consideration by the Supreme Court. The hearing was held in October and judgment is awaited.

In May 2020, the High Court (UK) dismissed ClientEarth’s judicial review challenge to the Secretary of State’s decision to grant development consent to build and operate two new gas-fired generating units at the Drax Power Station. When granting consent, the Secretary of State noted “the significant adverse impact” of the development in terms of the amount of GHG emissions that would be emitted, but concluded that they did not afford a reason to refuse consent. This was because the policy objectives of a national policy statement (NPS) for nationally significant energy infrastructure assumed a continued need for fossil fuel power generation and the development of the Drax Power Station would be a significant contribution towards this.

ClientEarth challenged the decision on eight grounds, including that the defendant had misinterpreted the NPS when assessing the project's GHG emissions and the assessment of the need for the development, and failed to fully consider the UK Government’s net zero target under the Climate Change Act 2008 (UK). ClientEarth argued that because of events since 2011 when the NPS was developed, including the adoption of the net zero target, there was no need for any future new large gas-fuelled power stations to be built.

In dismissing the claim, the Court agreed with the defendant’s interpretation that the NPS assumed a general need for fossil fuel power generation, and held that the award of the development consent was in accordance with the NPS, notwithstanding the GHG emissions that would be generated as a result.

In July 2020, the Court of Appeal granted ClientEarth’s application to appeal the High Court’s decision. The appeal was heard in mid-November and judgment is awaited.

In May 2020, following on from the above case, separate proceedings were commenced by Dale Vince, CEO of Ecotricity, journalist George Monbiot, and the Good Law Project, seeking judicial review of six national policy statements (NPS) for energy infrastructure issued by the UK Government in 2011. The claimants argue that the NPSs should be reviewed in light of new British and global climate commitments.

In this case, the claimants allege that the Government is required by the Planning Act 2008 (UK) to review the NPSs in light of the Paris Agreement, the amendment to the Climate Change Act 2008 (UK) last year to set the UK’s net zero target by 2050, the Parliament’s declaration of a climate emergency, the IPCC Special report on 1.5 degrees of warming and UK’s exit from the European Union. The claimants also allege that the NPSs unlawfully frustrate the intention of Parliament, which approved the amendment of the Climate Change Act to set the net zero target.

The claimants seek a declaration that the government must review the NPSs or, alternatively, that the NPSs are unlawful.

Increasingly, it can be expected that challenges will be lodged in relation to developments which are likely to generate significant GHG emissions and policies that continue to support fossil fuel developments, particularly in a context where these developments are inconsistent with the goals of, and commitments made under, the Paris Agreement.

As we have seen with the Heathrow Airport decision in the UK and Rocky Hill decision in Australia (see our update here), the courts will, in appropriate circumstances, use international or national policies, laws or regulation to refuse new development that will intensify climate change or conversely, suffer from the future impacts caused by climate change.

Administrative law claims involve those against governments challenging the application and enforcement of climate change legislation and policy. Often these cases overlap with planning and permitting laws challenging decisions on individual projects, as set out above.

In September 2020, 8 young Australians commenced a class action in the Federal Court of Australia, seeking an injunction to restrain the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment from approving Whitehaven’s proposed Vickery coal mine expansion in New South Wales. The proceedings were commenced on behalf of the applicants and all children born before the commencement date of the proceeding.

The application contends that the Minister owes the applicants, as young Australians, a common law duty of care, and approving the mine expansion will accelerate climate change and therefore breach that duty. The intention of the applicants is to “set a precedent that would prevent all new coal mines from being approved in this country.”

The success of Urgenda in 2015 prompted debate in academic and legal circles about the potential for, and hurdles involved in, running similar litigation based on tort law in Australia.13 Five years on, Sharma will test the duty of care approach in Australia. For the claim to be successful, it will require the Court to first find a duty of care is owed by the Minister to the applicants before addressing the separate question of whether approving the coal mine expansion is a breach of that duty. There would be significant precedent implications for Australian climate litigation if either of these are proven by the applicants. If the Court holds that the Minister owes such a duty of care, it could potentially create a risk of legal action in connection with the approval of any GHG emitting projects.

A law student filed proceedings in the Federal Court of Australia in July 2020 against the Australian government and select government officers, including the Secretary to the Department of Treasury and the Chief Executive of the Australian Office of Financial Management, for failing to adequately disclose climate change risks to the value of government bonds to investors. The claim suggests that climate change is a risk to the value of investments in government bonds, which must be disclosed to potential investors as it is material to an investor’s decision to trade in such bonds. It appears to be the first case globally to make this claim but draws on similar cases against private companies involving misleading disclosure and directors’ duties.

O’Donnell’s claim has two limbs: first, the government breached its duties under s 12DA(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) by engaging in misleading or deceptive conduct by promoting the bonds without disclosure of Australia’s climate risk; and second, breach of the duty under s 25(1) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (Cth) by failing to exercise functions with reasonable care and diligence.

O’Donnell is seeking a declaration that the duties were breached, and also an injunction preventing the government from promoting bonds until it updates its disclosure policies.

If the claim is successful, the case may have consequences for duties to disclose climate risks for government and private sector investment providers.

On 8 September 2020, Friends of the Earth brought a claim under the Aarhus Convention challenging the UK Government’s decision to provide USD 1 billion in financial support for the development of an LNG project with Total in Mozambique.

Friends of the Earth is challenging the legality of decisions made by the Secretary of State, HM Treasury and UK Export Finance in respect of the project under Articles 9(1) and Article 9(3) of the Aarhus Convention. The claim for judicial review is based on the following grounds: (i) unlawful failure by the UK Government to follow its own policy in relation to international standards, transparency and accountability; and (ii) unlawful failure to take account of relevant factors, including compliance with relevant applicable standards and benchmarking.

Friends of the Earth has stated that the investment also breaches “a number of other international law standards on the environment and human rights” and has criticised the decision of UK Export Finance to withhold disclosure of the assessment undertaken in respect of the environmental impact of the project. It is also argued that the investment failed to properly consider the UK’s commitments under the Paris Agreement.

The case is ongoing.

The above cases illustrate the willingness of litigants, particularly those physically affected by climate-related natural disasters or disproportionately affected by climate change, and living in jurisdictions where there is no human rights or constitutional basis, to explore new causes of action to hold governments to account.

The willingness of courts to embrace new arguments and establish new precedents against governments in climate change litigation should be closely monitored, given that such claims could signal a precursor for action against private sector parties.

Although any impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on climate change litigation are yet to be realised, we expect the momentum of increasing climate litigation to continue into 2021 to achieve outcomes consistent with a net zero emission future. This is particularly because “[r]ecord heat, ice loss, wildfires, floods and droughts continue to worsen, affecting communities, nations and economies around the world”.14 Further, according to an Australian Government report, “[c]oncentrations of all the major long-lived greenhouse gases in the atmosphere continue to increase” and “[d]espite a decline in global fossil fuel emissions of CO2 in 2020 associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, this will have negligible impact in terms of climate change”.15

While governments continue to be the most likely defendant in climate change litigation, we expect the trend in bringing claims against corporations to continue. In addition to new claims against major carbon emitting entities, we expect that cases against other corporates, such as financial institutions and investors, will also increase as communities and shareholders seek accountability for their role in GHG mitigation.

Please contact a member of our climate change team if you would like further information about any of the cases covered in this update, or would like to discuss climate change issues more generally.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions to this article by Daniel Wells, Krista Macpherson, Ashleigh McCoach, Emilija Rupsys, Sebastian Withers, Chelsea Zwoerner, Zara Nadeem, Eddie Skolnick and Madeline Hallwright.

“Global trends in Climate Change Litigation: 2020 Snapshot”, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science, July 2020 (Grantham Institute Report).

See Climate Case Chart (http://climatecasechart.com/). Note some numbers are currently being confirmed.

Grantham Institute Report.

Notice of Appeal, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/571d109b04426270152febe0/t/5fbd60f6522c3c68e63fef2d/1606246646837/Notice+of+Appeal+2020+11+24+FILED.pdf.

See e.g. American Electric Power Co. v Connecticut 564 U.S. 410, (2011) (Connecticut); Comer v. Murphy Oil USA, Inc., 585 F.3d 855 (5th Cir. 2009) (Comer).

Except a few cases such as State of Connecticut v Exxon Mobil Corporation commenced in September 2020.

Australian Super made a net zero announcement on 12 November 2020 https://www.australiansuper.com/superannuation/superannuation-articles/2020/11/committing-to-net-zero-by-2050.

See e.g. Peel, Jacqueline, Osofsky, Hari, Foerster, Anita, Shaping the 'Next Generation' of Climate Change Litigation in Australia (2017) 41(2) Melbourne University Law Review 793.

Event

The Insurathon is a Norton Rose Fulbright event which fosters technological advancements and innovation in the insurance sector, now in its eighth year.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025