Having commenced on 4 January 2022, the UK’s new national security regime has now been in force for more than 12 months. Introduced by the National Security and Investment Act 2021 (NSI Act), the new regime has had a significant impact on deal-planning, considerably expanding the number and types of transactions subject to UK national security reviews, as well as introducing, for the first time, mandatory notification requirements alongside voluntary filings.1 While non-compliance risks serious civil and criminal sanctions, the real headline has been the number of deals that have required remedies or been prohibited outright. So, what are the key themes which have emerged in the first year?

In summary:

- 14 transactions received a final order in 2022 – meaning they were found to raise substantive national security concerns and were either prohibited (five transactions) or required remedies for clearance (nine transactions). Out of hundreds of transactions which have been reviewed, as expected, the vast majority were cleared unconditionally.

- Three of the five prohibitions related to anticipated acquisitions. The other two were in respect of transactions that had completed before 4 January 2022 (Nexperia/Newport Wafer Fab and LetterOne/Upp Corporation). This is because the NSI Act enables the review of relevant “trigger events” which took place on or after 12 November 2020.

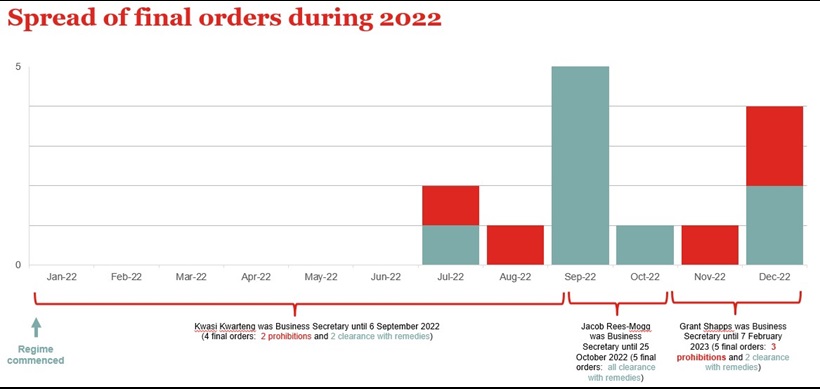

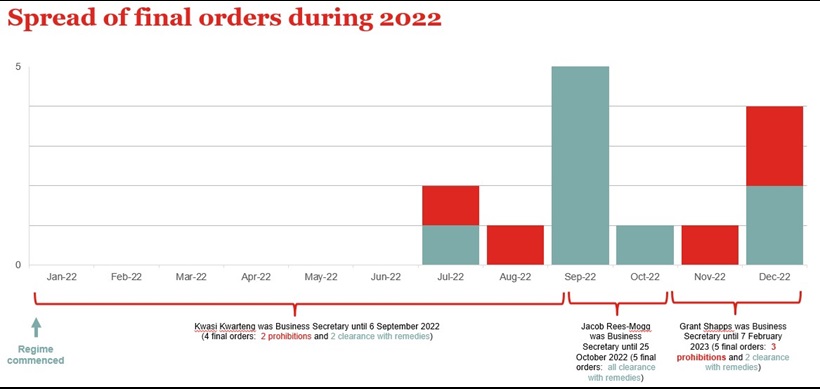

- There have been several changes of Business Secretary over the past year, with the Business Secretary being the ultimate decision-maker on any NSI review during 2022. Each case will turn on its facts, but interestingly most of the prohibitions were made after Grant Shapps became Business Secretary on 25 October 2022 (he made five final orders in 2022, three being prohibitions). Going forwards, the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster/Secretary of State in the Cabinet Office, currently Oliver Dowden, will be the decision-maker on NSI reviews, with the Investment Security Unit (ISU) moved to the Cabinet Office in February 20232.

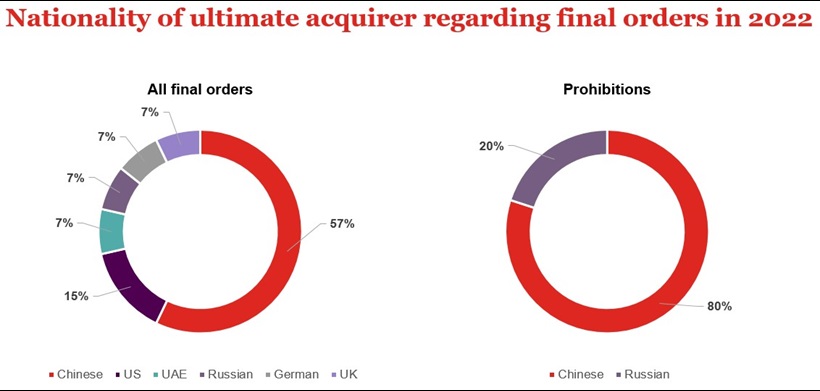

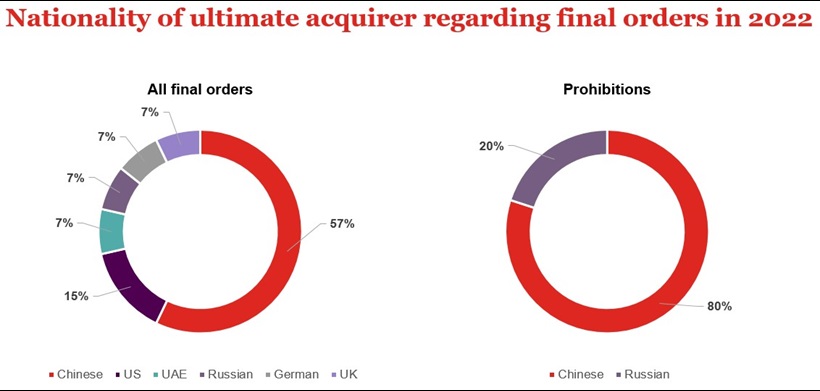

- The nationality of ultimate owners of acquirers that received final orders in 2022 has in the main been Chinese (eight of the 14 final orders). Chinese nationality is particularly notable in relation to the five acquirers whose deals have been prohibited. Four of the five appear to be Chinese, with at least three of those acquirers being owned by or having links with the Chinese state.

- Transparency and clarity, or perhaps more accurately the perception of the lack of these, remain concerns regarding the new regime. The very broad scope also continues to be an issue in terms of the number of transactions falling within the scope of the regime, especially given the low number found to raise substantive concerns. The ISU has also been increasingly reluctant to offer specific guidance, requiring parties to determine for themselves whether they are subject to the regime by reference to the published guidance, despite the various ambiguities and inconsistencies parties have raised with them in this respect.

We set out below further information about the first year of the NSI regime. To learn more about the main aspects of the regime and for our decision tree to help identify transactions that may require notification, see also our separate briefing here.

What kinds of transactions have raised concerns?

As expected, the vast majority of reviews have not found substantive concerns. The then Business Secretary’s first annual report on the regime, published in June 2022, revealed 222 notifications were submitted during the first three months of 2022, resulting in 17 notified transactions being called-in for a full assessment (i.e. an in-depth/second stage review). Data for the first full year is not expected until the next annual report, but it is already clear hundreds of transactions were reviewed in 2022 – all cleared unconditionally except the 14 that received final orders.

Relatively little information has been revealed about those transactions raising concerns – only one-page notices of final orders (not the full final orders themselves) have been published, providing brief details of the relevant transaction, parties, concerns and remedies. Some further information on transactions that have received final orders is expected in the next annual report, but this is unlikely to contain in-depth information about individual transactions.

Despite their lack of detail, the published notices of final orders demonstrate links to the risk factors set out in the Secretary of State's statement on use of the call-in power, the only real guidance on substantive concerns. The statement sets out three risk factors that are key to whether a transaction is likely to receive a call-in notice (i.e. proceed to a full assessment because there may be concerns):

- Target risk – whether the target entity or asset is being used, or could be used, in a way that poses a risk to national security.

- Acquirer risk – whether the acquirer has characteristics that suggest there is, or may be, a risk to national security from the acquirer having control of the target.

- Control risk – whether the amount of control that has been, or will be, acquired poses a risk to national security (a higher level of control may increase the level of national security risk).

In terms of target risk, qualifying acquisitions in any area of the economy can be reviewed, but a transaction is unlikely to be called-in unless the target entity or asset is in one of the 17 mandatory notification sectors or a closely-linked sector. The published notices of final orders do not explicitly identify relevant sectors, although the final orders so far broadly concern transactions regarding dual-use technologies, semi-conductors, communications, aerospace and/or energy.

Acquirer risk is arguably the most significant of the three risk factors as to whether a transaction is likely to require remedies or be prohibited. There is an apparent focus on China, noting the number of final orders involving acquirers owned by Chinese entities, and generally with links to or owned by the Chinese state. The UK Government has articulated concerns about Chinese investment in the UK from a national security perspective on a number of occasions,3 although it has not been specifically articulated that a Chinese buyer constitutes high acquirer risk under the NSI regime – even if this may appear to be the case in practice.

While eight of the final orders involved Chinese acquirers, the other six concerned acquirers from the US (two), UAE, Russia, Germany and the UK. Like the previous Enterprise Act regime, concerns can therefore arise even if an acquirer is from a “friendly” state such as the US or Germany. Also, the regime’s broad scope means even entirely UK transactions can require notification, despite being highly unlikely to raise substantive concerns. The one final order issued to a UK-owned acquirer in 2022 (Epiris LLP, whose acquisition of Sepura Ltd was cleared with remedies) is an outlier in this regard, possibly influenced by the seller being subject to undertakings under the old Enterprise Act regime and Sepura’s activities being deemed critical to communications between the UK emergency services.

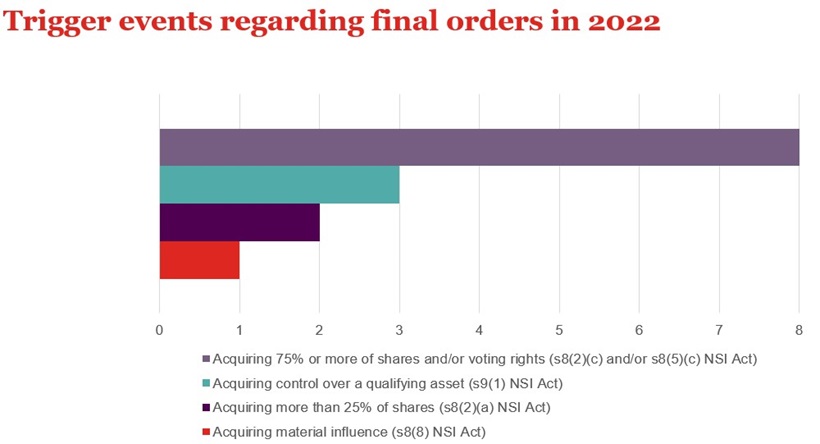

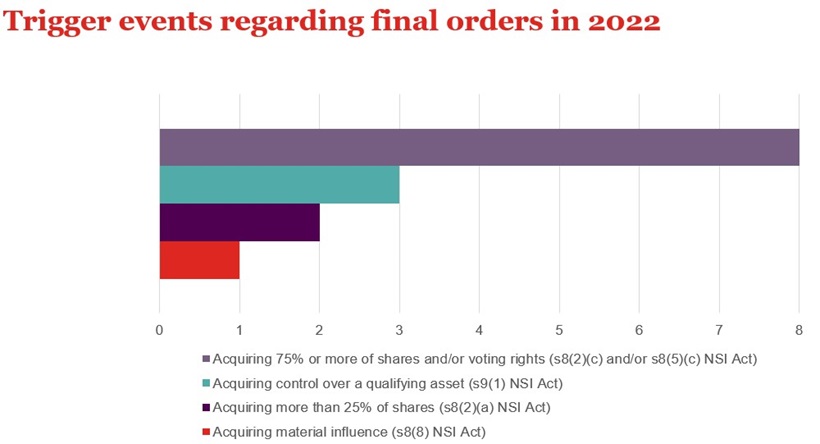

Eight of the 14 final orders in 2022 involved transactions where the acquirer was acquiring 75 per cent or more of shares or voting rights of a qualifying entity (the highest level of trigger event). Concerns have also arisen at lower levels – two of the 14 final orders concern an acquisition of shares at the “more than 25 per cent” trigger event, and another involves an acquisition of material influence. But all three of those transactions were cleared with remedies, not prohibited.

Prohibited transactions that completed before 4 January 2022

Although the NSI regime commenced on 4 January 2022, the NSI Act also enables transactions to be called-in for a retrospective review if a relevant trigger event took place between 12 November 2020 (the day after the Bill that became the NSI Act was published) and 3 January 2022, subject to certain limitation periods. Two of the final orders in 2022 relate to such transactions.

The first was Nexperia BV’s acquisition of Newport Wafer Fab (which makes semi-conductor wafers), arguably the highest profile review to date. Nexperia already owned 14 per cent of Newport Wafer Fab before acquiring the remaining 86 per cent in July 2021. Then Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, indicated the National Security Adviser would look into the transaction, but in April 2022 the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee queried whether any review had started. Shortly thereafter (in May 2022), the transaction was called-in for a full assessment, which (after several changes of Prime Minister and Business Secretary and almost six months – much longer than the standard 30 working days) concluded in prohibition on 16 November 2022 and Nexperia being required to sell at least 86 per cent of its shares. Although not stated in the published notice of the final order, reports suggest Nexperia (a Dutch entity) is backed by the Chinese state (possibly even 30 per cent owned by China), with this believed key to the prohibition. Nexperia has criticised this outcome, claiming it offered far-reaching remedies that would address any concerns and is now seeking to challenge the final order by way of judicial review – the first time a final order has been challenged.

The second is L1T FM Holdings UK Ltd’s acquisition of Upp Corporation Ltd (formerly Fibre Me Limited) which was completed in January 2021. This transaction was prohibited on 19 December 2022, due to concerns about the ultimate beneficial owners of LetterOne Core Investments S.à r.l (the acquirer’s parent company) and Upp’s expanding full fibre broadband network. While LetterOne is a Luxembourg-based investment manager, it is owned by several Russian oligarchs sanctioned due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. LetterOne must sell 100 per cent of Upp, and Upp must complete a security audit of its network prior to sale. This outcome is despite LetterOne’s attempts to distance itself from its sanctioned shareholders.

Have any transactions under the voluntary notification regime raised concerns?

Yes. At least four final orders in 2022 concerned transactions under the voluntary regime (three asset acquisitions and one acquisition of material influence – which involve trigger events outside the mandatory regime). Notably, one of these (a proposed IP licence agreement regarding SCAMP-5 and SCAMP-7 vision sensing technology between the University of Manchester and Beijing Infinite Vision Technology Company Ltd), was prohibited in July 2022 – the first transaction to be prohibited under the NSI Act.

Are there notable transactions that have not raised concerns?

Very little has been made public about transactions that have been found not to raise concerns. Clearance decisions are not published for transactions reviewed and unconditionally cleared, and the Business Secretary/BEIS have not typically commented on these.

A rare exception is the acquisition by French/Dutch company Altice of 5.9 per cent of BT in December 2021 (taking its shareholding to 18 per cent), which BEIS announced had been called-in in May 2022 and which was cleared unconditionally in August 2022. Also, on 7 December 2022, BEIS announced no further action would be taken regarding the acquisition of Aveva Group Plc by Ascot Acquisition Holdings Limited (an indirect subsidiary of Schneider Electric SE), which was notified in October 2022.

What kinds of remedies have been required for transactions cleared with conditions?

As mentioned above, published notices of final orders only briefly describe remedies. One of the first notices merely stated conditions had been imposed without elaborating (Tawazun Strategic Development Fund LLC/Reaction Engines Limited), but more recent notices at least give an indication.

In most cases, the remedies involve conditions to protect sensitive information, or possibly IP or technology. Some conditions involve requirements to keep certain capabilities in the UK. Other conditions have included restrictions on board representation or requiring a UK Government observer on the target’s board. Transactions cleared with remedies in the energy sector have also included requirements to obtain UK Government approval regarding offtake operators.

Will the number of final orders increase in 2023?

Ultimately this will depend on how many transactions are deemed to raise serious national security concerns. In terms of what the pattern of final orders in 2022 can tell us, there were no final orders during the first half of the year, with peaks and troughs during the final six months (e.g. five final orders in September, one each in October and November and four in December). It seems highly unlikely that we will see another six-month period without any final orders being made, but for 2023 it will be interesting to see whether the overall number of final orders is similar to last year (albeit more evenly distributed) or whether numbers will increase.

2022 was an exceptional year in terms of the absence of continuity at ministerial level (which has continued into 2023), although it is difficult to draw any firm conclusions about whether the changes of Business Secretary affected the number of final orders during the first year. A lack of final orders in the first two or three months of the regime was to be expected (given notified transactions typically take at least two months to reach the point at which a final order could be made,4 and the regime still bedding in), but the first final order was not until July 2022. There were signs towards the end of 2022 that final orders, in particular prohibitions, might be increasing under Grant Shapps (he prohibited three transactions during November and December), after the slower start under Kwasi Kwarteng. However, the apparent increase did not continue in January 2023 – there were no final orders in January.

On 7 February 2023, it was announced that BEIS would be split into a number of different departments, with the ISU moved to the Cabinet Office and Oliver Dowden (Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and Secretary of State in the Cabinet Office) taking over from Grant Shapps as the relevant Secretary of State and therefore decision-maker for NSI reviews. It will be interesting to see whether this leads to any discernible change in how the regime is applied, including the number and nature of final orders.

Can final orders be varied or revoked?

Yes – the NSI Act provides for final orders to be varied or revoked. One of the final orders made in 2022 clearing a transaction with remedies was revoked later in the year after the transaction was abandoned.

A notice of variation was also published in January 2023 regarding the final order made in July 2022 prohibiting the proposed licence agreement between the University of Manchester and Beijing Infinite Vision Technology mentioned above. That licence agreement continues to be prohibited, but the variation clarifies the University’s obligations regarding its employees and allows it to share the relevant technology in certain circumstances subject to the Secretary of State's agreement. It is notable that the notice published in July 2022 is silent about employees or broader sharing of the technology – reflecting that obligations in final orders may be more extensive than published notices suggest.

Is the regime too broad?

The NSI Act is deliberately broad and flexible (e.g. national security is not defined), enabling the regime to remain “fit for purpose” as national security concerns evolve. But this is at the expense of certainty and arguably means hundreds (or even thousands) of transactions unnecessarily reviewed each year.

Kwasi Kwarteng suggested that the regime may be catching too many transactions that do not raise substantive concerns. However, he has also highlighted the ability of the regime to capture smaller transactions, such as Super Orange HK Holding Ltd/Pulsic Limited, prohibited in August 2022.

Something to watch is whether certain types of acquirers may be exempted from mandatory notifications in future. Market Guidance Notes published in July 2022 state the Government is monitoring closely how the NSI Act works in practice, analysing trends and risks to determine whether exemptions to the mandatory notification requirements are appropriate. Updated and more specific guidance will definitely be welcomed by parties, given the ISU’s increasing reluctance to provide guidance on interpretation of the rules – with the default approach being simply to ask parties to make a filing if unsure.

The devil is in the detail – or the lack of detail

In addition to the very broad scope of the regime, as noted above, a lack of clarity regarding important aspects of the applicability of the regime has made it difficult for parties to apply in practice. Despite various guidance materials published at the outset of the regime and the Market Guidance Notes in July 2022, the regime remains complex and there are several areas where the rules are unclear. This includes the definitions for the 17 sectors subject to mandatory notification.

While BEIS published guidance on the sector definitions, often this does little to clarify what is caught (e.g. the definition for “advanced materials” runs to 13 pages, but the guidance on that definition is around a page and does not explain any of the technical terms used). A number of the sector definitions are also closely-related and care is needed in this regard. As an example, BEIS guidance explains that self-driving cars and core capabilities of autonomy underpinning them fall within the definition for “advanced robotics” but automated parking and lane departure warning capabilities do not. However, the same guidance indicates automated vehicle parking systems are within the “artificial intelligence” definition.

If it is uncertain whether a target’s activities fall within one of the 17 sectors, parties are encouraged by the ISU to notify “just in case”, but this requires the parties to take a view on whether their deal falls within the mandatory notification requirements (which may set an unhelpful precedent for them). There are separate forms for mandatory and voluntary notifications, and a notification will be rejected if the wrong form is used. More flexibility in this regard would be beneficial.

While the sensitivity of national security concerns, and the importance of confidentiality, are understood, the absence of detailed published decisions on reviewed transactions means that the regime does not provide case-law (as, e.g. under competition filing regimes) which can be informative for parties in determining their approach, or clarifying whether certain activities fall within the sector definitions for mandatory notification. In the absence of published decisions, additional Market Guidance Notes will be the most likely – and welcome – source of further clarification.

Engagement with the ISU and Secretary of State

As mentioned above, in the early stages of the regime, parties were encouraged to contact the ISU with any questions via the ISU’s general email address. However, in our experience, responses can take several months and may not necessarily provide certainty, with the ISU apparently lacking the resource or willingness to answer questions unless linked to a live transaction.

Perhaps this is also related to the fact that parties are not assigned a case team or dedicated contact when they submit a notification (or respond to an information request). This makes it difficult to know how a review is progressing, although in the vast majority of cases the outcome is unconditional clearance with no full assessment or need for remedies.

The NSI Act provides that before making a final order the Secretary of State must consider any representations made, but there appears an unwillingness to engage in dialogue with parties even at this stage. The extent of the Secretary of State’s obligations in this regard may be clarified by Nexperia’s judicial review challenge to the final order regarding its acquisition of Newport Wafer Fab – Nexperia has suggested it had “no dialogue” regarding remedies it offered and believed were adequate.

In this context, we may find that the greatest insights into the workings of the NSI Act come from legal challenges and judgments on how the Secretary of State/ISU have carried out their functions. A year in, we can certainly see the regime has been able to process a large number of reviews – and to intervene in a number of cases. But the NSI regime remains opaque, and can be slow in a transactional context. This is in contrast to competition regimes, where parties expect to be able to interact with decision-makers and see clear reasoning for decisions. This is unsurprising in a national security context, but makes it harder for parties to understand from the outside. Given the breadth of the regime, it remains likely that there is material under-notification of transactions technically caught by the mandatory powers, but we have yet to see examples of the Secretary of State seeking to sanction such deals.