Publication

Australia’s new mandatory merger control regime

Mergers or acquisitions that meet certain turnover thresholds will shortly be required to be notified to the ACCC.

Author:

Australia | Publication | May 2021

Competition law was designed with competition between brands in mind, and also poses risks in an era when brands have multiple competing channels to market. This article highlights the top five competition law risks that require navigation in an increasingly omni-channel world.

When competition laws originated, the world was a simpler place. Other organisations were either competitors, or not. In a standard supply chain, everyone had their own level, and the arrangements were therefore clearly vertical. These days, it is rare for there to be single supply channels. More common are dual structures comprising bricks and mortar and online channels; intermediaries such as Ebay and Amazon have created additional channels to market. Omni-channel distribution is now used by most major brands.

Markets are also often dissected along product, geographical or customer grounds, with various types of networks established. In implementing those networks, manufacturers and brand owners may act in their own capacities and/or appoint licensees, franchisees, distributors, agents, or a combination.

Whilst often commercially and legally sound, competition law risks increase:

This article elaborates on how these risks can manifest, lists five key risks under the Australian Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CCA) and provides some current and recent case examples.

The CCA relevantly prohibits:

The formal legal prohibitions are explained in the Appendix at the end of this article.

Resale price maintenance (RPM) refers to vertical price control where a supplier:

There is no economic or business justification that can save RPM conduct from illegality in Australia, unless authorisation for the conduct is sought and obtained from the ACCC prior to engaging in that conduct. As a consequence, resellers have the right to discount at their discretion.

Nonetheless, it is generally permissible:

| Case example: 2019: Bromic Pty Ltd gave a court-enforceable undertaking to the ACCC. It admitted that it required retailers not to advertise Bromic branded heating products for sale at a price cheaper than a price determined by Bromic, including through implementing a ‘three strikes’ policy for those that did not comply. |

It is common for a supplier to mandate that its distributor or other representative only operate in specified areas or under other constraints. Also, a representative may seek to prevent the supplier from supply rights (or only allow limited supply rights) in competition with that representative.

This is often referred to as exclusive dealing, in that the supply or acquisition of goods or services is conditional on dealings being implemented in a way that preserves exclusive or protected segments, be it territories, functional levels of the market, suppliers or customers.

Another category of exclusive dealing, known as “third line forcing”, arises where a supplier mandates that its customer acquire goods or services from specified third parties.

Whilst inherently affecting competitive dynamics, such arrangements often derive from legitimate efficiency drivers and often support effective investment and management of resources and channels. As such, exclusive dealing is only prohibited if it has the purpose, effect or likely effect, of substantially lessening competition.

Exclusivity becomes problematic if it has the purpose or effect of meaningfully foreclosing choice and access by customers to suppliers (and vice versa). This will be made more likely if any aspect of the supply chain is scarce and the restraints (in terms of duration or scope) cannot be justified.

| Case example: 2018: Parties involved in exclusive channel division in the hardware and home building sectors, paid total penalties of more than $11 million. In essence, two distributors agreed with an upstream supplier to buy its products on condition that the upstream manufacturer did not supply direct to retailers (who were served by the distributors). |

A supplier / franchisor may participate directly in downstream supply markets itself, not just through distributors or other representatives. Sometimes, then, the supplier / franchisor might compete across customers, geography and/or product/service type with its own supply chain.

Interactions about prices, customer allocations or other strategic matters in those circumstances carry a heightened risk. This is because what might have been permissible in a vertical supply context, is prohibited outright by the prohibitions against cartel conduct, summarised in the Appendix.

Sometimes the cartel issues can be inadvertent, raised by unclear or incorrect legal or operational structuring. However, they can be more overt.

A good example of an overlapping model is where a manufacturer may run the website and online sales for a product and the franchisees or local distributor are allowed to run physical sales. Most simply, this constitutes market sharing (in so far as the distributor and the manufacturer have agreed to “coexist” and serve different consumer bases). This can usually be managed by appropriate drafting and structuring of the franchise agreement or supply contracts to take advantage of an exception to the cartel conduct. The exception allows such arrangements where they constitute exclusive dealing (as outlined above), and assuming they do not have the purpose or effect of substantially lessening competition.

However, further risks arise because the manufacturer and distributor have to act at ‘arms-length’ and not otherwise coordinate on matters such as pricing, insofar as their customer bases may overlap.

Appointment of agents, instead of distributors, can offer some competition law cover, particularly if price control is an imperative.

However:

Here are a few tips:

Our competition and consumer markets teams at Norton Rose Fulbright are adept at advising on and supporting compliant channel models. Please contact us if you need assistance.

Cartel conduct involves entering into (or giving effect to) a contract, arrangement or understanding (CAU) where two or more parties are competitors or potential competitors, containing a provision that:

The extent of the likely impact on the market is not relevant. Cartel conduct is prohibited outright unless an exception applies.

Resale price maintenance (RPM) occurs when a supplier does not let its customers advertise or sell below a specified price. RPM is also prohibited outright irrespective of its effect on competition.

Also prohibited are:

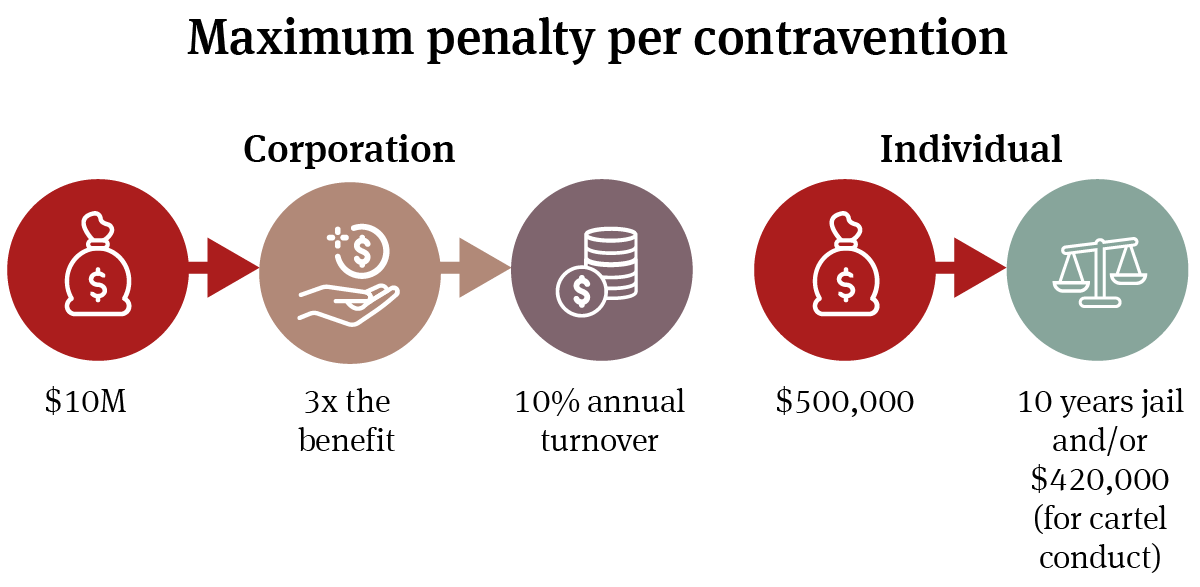

Contravention of these prohibitions can result in significant financial penalties for companies and individuals involved.

Publication

Mergers or acquisitions that meet certain turnover thresholds will shortly be required to be notified to the ACCC.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2026