Publication

Power market high wire act for generators

In December last year, the Federal Court dismissed a class action alleging that Queensland’s State-owned generators misused their market power to drive wholesale power prices higher.

The Belt & Road Initiative (B&R) is without a doubt the most ambitious, strategic interconnected infrastructure initiative devised in recent memory.

Launched by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, the initiative aims to connect major Eurasian economies through infrastructure, trade and investment. It will see a RMB1.5 trillion infrastructure investment pipeline1 stretching over 10,000 km over more than 60 countries with a total population of 4.4 billion2 and 40% of global GDP3 across Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa, and cover projects across the infrastructure and energy sectors from small scale renewables to large scale integrated mining, power and transport projects. After its announcement in 2015, over 1400 contracts worth over US$37 billion were signed by Chinese companies in the first half of 2015.4

Full details of both the project pipeline and the specific requirements for a project to qualify as a B&R project are still not fully certain. What is clear is that the potential opportunities for infrastructure investment are immense.

For any host country or investor interested in infrastructure in B&R regions, Chinese capital cannot be ignored. Tapping it can be difficult but a foreign investor who can navigate the issues involved is potentially unlocking the key source of capital and equipment for the B&R regions’ major projects over the next fifteen years.

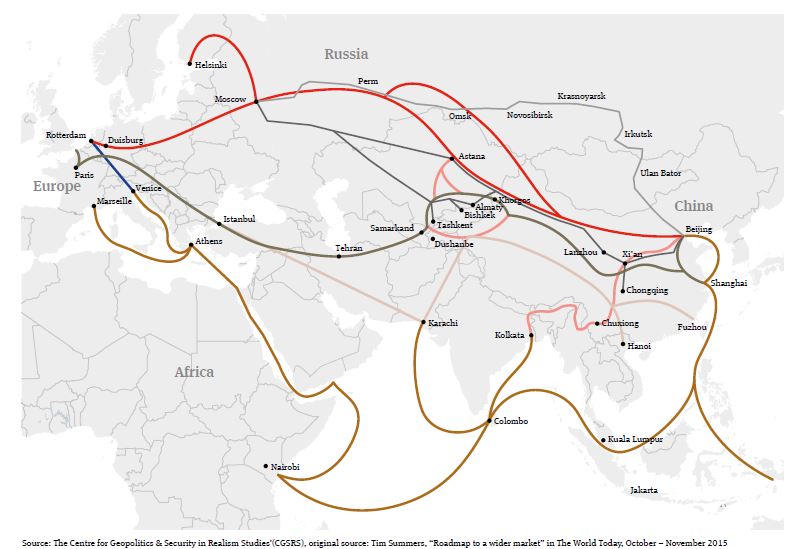

The Belt & Road Initiative has two main elements: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.

The Silk Road Economic Belt will be an overland network of road, rail and pipelines roughly following the old Silk Road trading route that will connect China’s east coast wih Europe via a new Eurasian land bridge. 5 regional corridors will branch off the land bridge, with Mongolia and Russia to the North, South East Asia, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh to the South, and central Asia, West Asia and Europe to the West.

The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road is a planned sea route with integrated port and coastal infrastructure projects running from China’s east coast to Europe, India, Africa and the Pacific through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean.

The geographic scope of the Belt & Road Initiative is fairly fluid and on some interpretations has also been extended to Australia and the UK.

A snapshot of the land corridors and a map showing both the Belt and the Road is set out overleaf.

| Economic Corridor | Countries include | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| New Eurasian Land Bridge (Jiangsu province to Rotterdam, Netherlands) | Central and Eastern Europe: Albania, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Serbia Western Europe: Netherlands, Germany |

Aim: new major road and rail logistics passageway from China to Europe which is faster than sea transport and cheaper than air routes. Project spotlight: international freight train line from Lianyungang via Xinjiang province to Kazakhstan (February 2015). Hot topic: covering 10,900km in length China is working with customs departments in countries such as Kazakhstan, Poland and Russia to reduce customs clearance costs along the route. |

| China – Mongolia – Russian Corridor (Beijing/Tianjin/ Hebei/Dalian to Russia) | Belarus, Moldova, Mongolia, Russia |

Aim: utilise existing international freight lines and construct a northern passageway to connect Beijing, Dalian and Tianjin with Western Europe. Project spotlight: Chinese contracts for high-speed rail, energy, infrastructure and aerospace worth US$25 billion signed with Belarus, Russia and Kazakhstan (May 2015). Hot topic: the corridor fits with Russia’s Transcontinental Rail Plan and Mongolia’s Prairie Road Programme. |

| China – Central Asia – West Asia Corridor | Central Asia: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan West Asia: Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, Yemen |

Aim: important gateway for oil and natural gas, running from Xinjiang to the Arabian Peninsula, Turkey and Iran. Project spotlight: Chinese contracts signed with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to work on trade facilitation and logistics. Hot topic: A Chinese consortium acquired a 64.5% stake in the Kumport container terminal in Turkey in September 2015, This was the largest foreign capital investment in Turkey to date.5 |

| China – Indochina Peninsula Corridor (Pearl River Delta Economic Circle (Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Shenzhen) to Indochina) | Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Vietnam |

Aim: greater expansion into markets traditionally dominated by Japan and Korea. Project spotlight: Chinese consortium awarded the contract for electrification and double-tracking of the Gemas – Johor Bahru rail route (December 2015). Hot topic: the route aligns with the plans of the Greater Mekong Sub-Region, an economic area formed by the Asian Development Bank. |

| China – Pakistan Corridor (Xinjiang province to Gwadar, Pakistan) | Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka |

Aim: shortcut to the Middle East and Africa via Dubai and Oman, bypassing the Strait of Malacca. Expansion into large–scale infrastructure projects, building on China’s previous focus on small scale renewables. This corridor is to some extent the test pilot for the Belt and Road Initiative and is expected to be a priority, given Pakistan’s lack of infrastructure development. Project spotlight: Chinese contracts signed worth approximately US$45 billion6 covering energy, ICT and transport infrastructure (April 2015). The US$1.95 billion 660MW Thar Coal project reached financial close in February 2016, the first integrated mining and power project in the corridor. Hot topic: the Indian government has opposed this route, as it passes through Kashmir. |

| Bangladesh – China – India – Myanmar Corridor | Bangladesh, India, Myanmar |

Aim: connect China with South Asia as part of China’s wider strategy for integration with western Asia, again reducing reliance on the Straits of Malacca. Project spotlight: Chinese contracts worth more than US$22 billion covering telecoms, steel, solar energy and film signed with India (May 2015).7 A 2,800km K (Kolkata) -2-K (Kunming) road is at the heart of the corridor. Hot topic: progress of the road has been difficult as a section passes through Arunachal Pradesh – an area both subject to a territorial dispute between China and India, and prone to insurgency. |

The primary goal is to create new trading routes and business opportunities within China and beyond. Behind this, the drivers (both official and unofficial) are complex, diverse and interconnected.

On a domestic level, China wants to stimulate regional investment to better integrate poorer inland provinces into the Chinese economy, and to mitigate urban migration, wealth disparity and unrest from ethnic minorities.

The B&R regions will serve as new markets for China’s production over-capacity, foreign exchange reserves and more recent economic slowdown, and give Chinese contractors and sponsors in the infrastructure sector opportunities for expansion into, and connectivity with, both established and emerging markets. A focus on manufacturing capacity relocation as opposed to exports will also help to mitigate rising labour costs and pollution concerns and help China to achieve its global emission reduction commitments.

The routes themselves will facilitate trade, cooperation and relationships with host countries and partners in developing projects along the routes. The sea route is also inspired by China’s ambition to become a global maritime power player.

The Belt & Road Initiative is part of a refocus of outward investment, for the Chinese economy and for Chinese diplomacy.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has estimated that US$750 billion per year is needed to fund infrastructure needs in Asia to 2020.8 The ADB and the World Bank have so far committed funds of only US$30 billion between them.9

Both state owned enterprises (SOEs) and state financial institutions are being directed by Beijing to invest in B&R projects, both to fund the development of the projects and as an outlet for excess liquidity domestically as a result of overcapacity and the Chinese downturn. The China Development Bank (CDB) has also reportedly reserved more than US$890 billion for the B&R area.

Chinese policy banks will be the main source of B&R finance. Recognising the need for dedicated funding to support the Initiative, and to address the regional shortage in funding, China has also launched two new financial institutions: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Silk Road Fund.

The AIIB is a multilateral development bank led by China and located in Beijing with a mandate for infrastructure investment across Asia Pacific and its member states. It is expected to work in a similar fashion to the ADB. Countries scrambled to join China as founding members, with over 50 signing up at its launch in 2015. The bank’s authorised capital is US$50 billion, planned to rise to US$100 billion over time. Funding obligations will align to investment stakes, with China taking a 30% stake. The AIIB is expected to be very active in funding B&R projects.

By contrast, the dedicated Silk Road Fund is funded mainly with Chinese capital and will focus on funding transport and other infrastructure, resources and connectivity projects across the B&R, with a focus on Asia. The initial US$40 billon seed capital is funded by the CDB, China Eximbank, the China Investment Corporation and SAFE (China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange). There are reports that the Silk Road funding has already been fully deployed. The ADB is also expected to be active in providing funding for projects in the B&R area and has recently signed a framework agreement with the Chinese government to this end.

The new financing institutions and directives to state-owned companies also have a secondary advantage of readjusting sources of capital in Asia to be driven by Asia, and with Beijing in the driving seat. A recent study found a clear shift in China’s lending focus. 51% of B&R loans from Chinese financial institutions in 2015 went to Asia, compared to 27% in 2013, when the lion’s share went to Africa.

As a government initiative focused on infrastructure development, the main players will be state-owned enterprises taking a contractor or sponsor role and financial institutions such as CDB, CEXIM, ICBC and SINOSURE active in the infrastructure space. Key Chinese EPC contractors and sponsors already active within B&R countries include CCCC, Harbin Electric, China Power Group, CMEC, Huaneng, China Rail, China Rail Construction, SEPCO, Power China and Datang.

Nuclear is an area to watch – China already has almost half of the global nuclear pipeline up to 2030, and a leading Chinese nuclear developer estimates 80% of the 300 new reactors planned by 2030 will be in B&R countries.

The traditional sweet spot for Chinese capital is emerging markets. The core B&R regions fall into this category. In these more difficult jurisdictions, Chinese pricing of kit and debt is competitive and Chinese funds can be deployed comparatively quickly. Such countries are typically not covered by commercial banks, are often perceived to have political risk and often have relaxed labour controls, allowing for the deployment of Chinese labour.

Foreign investors willing to take a degree of country risk and co-invest with China in such jurisdictions can take advantage of Chinese capital and these associated benefits. The most important of these is the commercial and political risk insurance cover provided by SINOSURE (the Chinese stateowned export credit insurance provider) to support Chinese companies, offering a partial fix for host country political risk. The fact that Chinese investors and contractors are often SOEs and that a project falls within the B&R Initiative framework, means that a foreign investor can take additional comfort from the full weight of the Chinese government sitting behind them, and the political relationships which the government will have with B&R countries. Ultimately a state owned offtaker will be less likely to default on projects financed by Chinese policy banks with the effect that Chinese banks should essentially achieve preferred creditor status similar to the multilaterals in much of the B&R.

On the flipside, for more established jurisdictions such as the Middle East and Turkey, China needs outside help and is looking to partner with well-known foreign companies who have a track record of doing business in these countries and are better able to win contracts.

So what do foreign investors and host countries need to look out for when looking at B&R investment opportunities?

CRCC is leading the B&R charge in the rail sector. A consortium led by CRCC is expected to be a favourite to win the construction contract for the Kuala Lumpur- Singapore high-speed railway, the first of its kind in Southeast Asia.10 In December 2015, the Malaysian government awarded a Chinese consortium, also led by CRCC, the contract for electrification and double-tracking of the Gemas – Johor Bahru route.11 In 2014 CRCC signed a US$11.97 billion contract with the Nigerian government to build a coastal railway line in the country.

Although the Belt & Road Initiative brings many opportunities for investors, there are still many challenges and risks. Differing economic and political situations of B&R countries means there are inherent risks, ranging from political instability and security concerns, to legal, regulatory and funding challenges. Potential investors will need to conduct detailed due diligence and understand project and financing structures as well as the legal and regulatory regimes of the countries along the B&R routes.

Geographically, some of the terrain is harsh, involving long distances, high costs and potential security and insurance concerns.

Some of the regions covered by B&R are plagued by territorial disputes and local wars, endangering the implementation of the Initiative. Religious extremism may jeopardise the safety of projects. Local corruption, tensions with neighbours and domestic issues may also hinder projects. Political risk guarantees may help, but these may not be available for all jurisdictions and projects, particularly those going across several borders.

Other examples of political instability were seen during the construction of the controversial Myitsone Hydropower Project in Myanmar, which was suspended due to NGO opposition in 2011.12 Likewise, the Sino-Thai railway project – featuring 873km dual tracks – has been protested against by Thai citizens.13 Works on the US$1.4 billion offshore Colombo Port City project being constructed by CCCC, which was suspended by the Sri Lankan government in March 2015, have only recently been resumed.14 The project was initially suspended because of regulatory and environmental concerns, and a perceived scope for lack of transparency.

Other countries have generally been supportive of the Belt & Road Initiative, recognising the scope for co-investment and cooperation, but some are wary of China’s potential ambitions locally and on the world stage.

From a financing perspective, low host country credit ratings may present a challenge. Co-financing sources would also be wider if the US and Japan agreed to join the AIIB as members, but the funding gap in Asia and other B&R countries will not be met by AIIB funding alone. For the B&R Initiative to be successful and sustainable, China will need to engage the private sector and the commercial banks.

Some B&R countries are likely to present regulatory challenges in project approvals and implementation, particularly at a local level. Traditionally, infrastructure projects require high-standard management, have long operating cycles and uncertain profits. Therefore, it is vital that investors have a clear understanding of the relevant legal systems, security structures and risk management profiles. Regulatory reform will also be needed both in China and to open up markets in B&R countries, including in the areas of financial integration, customs clearance, antibribery and foreign investment.

When it comes to identifying enforcement risks, foreign investors tend to over-emphasise enforcement risks when dealing with a Chinese EPC contractor. Chinese parent company guarantees will invariably be with a mainland Chinese state owned enterprise, probably based in Beijing. This means a Singapore, London or Hong Kong arbitration award may ultimately need to be enforced in courts in Beijing. China has introduced procedures to ensure that such awards are readily enforced in China, and in practice, this should usually be the case. However, occasionally sponsors have encountered issues calling bank guarantees from Chinese banks. Chinese law allows a PRC court to claim jurisdiction to restrain a call on the bank guarantee where there is any claim of fraud. This risk should not be overstated, but sponsors should still consider asking for bank guarantees issued by a non-Chinese bank.

More generally, the current world economy remains unstable and investment appetite uncertain.

For B&R to be fully successful, projects need to get built quickly. Perhaps the biggest impediment is different standards. The B&R Initiative covers more than 60 countries, with different regulatory regimes, tax systems, forex controls and engineering standards. One aim could be to standardise the selection of projects and even seek to standardise non-sector specific requirements for B&R projects in a host country. More private sector involvement from China could also speed up project deployment as SOE requirements would not apply.

Publication

In December last year, the Federal Court dismissed a class action alleging that Queensland’s State-owned generators misused their market power to drive wholesale power prices higher.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025