Why a new Consumer Duty?

The introduction of the new Consumer Duty is driven by the need to strengthen consumer protection in retail financial markets, within a framework which incentivises vigorous competition in the interests of consumers, and within which consumers are empowered to make informed choices about financial products and services.4

The Consumer Principle does not change the nature of a firm’s relationship with its consumers. For example, it does not create a fiduciary relationship where one would not otherwise exist, nor require a firm to carry out any regulated activity (for example, provide advice) where it would not otherwise have done so.

The FCA conducted an extensive consultation process on the proposed Consumer Duty in two consultation papers (CP21/13 – Consultation Paper released May 2021; CP21/36 – Draft Rules and Guidance released December 2021). The Policy Statement and final rules were published on 27 July 2022, with an implementation timetable for businesses to meet, requiring that:

- by 31 October 2022 firms’ boards (or equivalent management body) should have agreed their implementation plans and be able to evidence they have scrutinised and challenged the plans to ensure they are deliverable and robust to meet the new standards;

- by 30 April 2023 manufacturers should aim to complete all the reviews necessary to meet the four outcome rules for their existing open products and services and share information with their distributors to enable them to meet their obligations under the Consumer Duty by this same date;

- by 31 July 2023, the Consumer Duty will apply to all new products and services and all existing products and services that remain on sale or open for renewal; and

- by 31 July 2024, the Consumer Duty will come fully into force and apply to all closed products and services.

The FCA has indicated that the Consumer Duty will be fundamental to its outcome-focused regulatory approach, which it believes can be applied more easily to technological updates and market developments than prescriptive rules in order to address consumer harm.5 Examples of consumer harms identified by the FCA include:

- firms exploiting consumers’ behavioural biases, through misleading presentation of information or general lack of transparency in the information they provide;

- firms selling products and services that are not fit for purpose, or not designed for the consumers they are being targeted at and sold to;

- firms selling products and services that do not represent fair value;

- firms providing poor customer support which presents an obstacle for consumers to take timely action to manage their financial affairs; and

- firms exploiting consumer loyalties or tendencies to remain with the same product or brand.

By embedding the Consumer Duty into its authorisation, supervision and enforcement approach, it will enable the FCA to increasingly focus on the outcomes that consumers experience. The FCA has stated that this, combined with its more “data-led” approach, should enable it to intervene more quickly than it has done previously where it identifies practices that have an adverse impact on customer outcomes and more assertively before those practices become entrenched as market norms.6

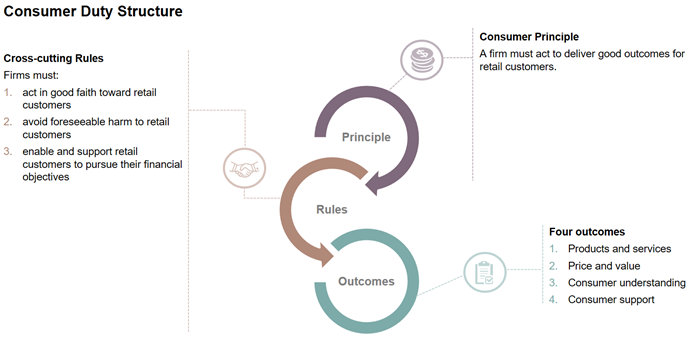

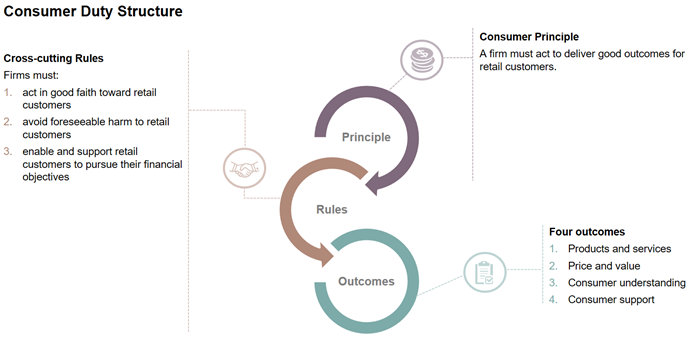

The diagram below captures the key elements of the new Consumer Duty:

Consumer Principle

The Consumer Principle (Principle 12) reflects the overall standards of behaviour the FCA wants from firms, and is developed by the other elements of the Consumer Duty.7

Principle 12 sets out FCA’s expectations of firm conduct – to think more about consumer outcomes and put consumers’ interests at the heart of their activities. It is expected to prompt firms to ask themselves questions such as whether they are treating consumers as they would expect to be treated in their circumstances.8

Principle 12 focuses on consumer outcomes, and requires businesses to:

- deliver beneficial outcomes for consumers generally, by pro-actively acting to put consumers’ interests first;

- focus on the outcomes for consumers, and ensure the business’ behaviour is aligned with how consumers actually behave and interact with products. This is to be achieved by better enabling consumers to access and assess relevant information, and pursue their financial objectives;

- ensure that all relevant sectors of the business have a well-founded understanding of consumer behaviour and how the products and services function to provide the outcomes that would reasonably be expected by those consumers;

- when good outcomes are not being achieved, act to fix any shortcomings in processes, systems or behaviours; and

- continuously and periodically review and improve themselves to ensure their actions align with the delivery of good outcomes for consumers.

The underlying purpose of the Consumer Principle is not to compel firms to protect individual customers from poor outcomes nor is it that consumers will always end up with a good outcome. Further, it also does not impose an open-ended duty to protect consumers from all potential harms. For example, firms, insofar as they have complied with the Consumer Duty, are not expected to protect consumers from risks that are inherent in a product’s structure or design, such as investment risks.

Cross-Cutting Rules

The Consumer Principle will be underpinned by a set of ‘cross-cutting’ rules which set out how firms should act to deliver good outcomes for retail customers and the standard of conduct that the FCA expects under Principle 12. They require firms to:

- act in good faith towards retail customers – this means conduct characterised by ‘honesty, fair and open dealing and acting consistently with the reasonable expectations of retail customers’. This is applicable to all stages of the customer journey and for the whole lifecycle of a product or service;9

- avoid causing foreseeable harm to retail customers – while this does not require firms to prevent all harms, it does mandate firms to take proactive and reactive steps to avoid foreseeable harm and put in place appropriate harm mitigation measures.;10 and

- enable and support retail consumers to pursue their financial objectives – including steps to facilitate retail customers to make informed decisions that are in their interests.11

The cross-cutting rules are intended to work together as a package, meaning that poor conduct may result in a breach of one or more cross-cutting rule.

Compliance with the cross-cutting rules is likely to require a consideration of how the new Consumer Duty interacts with existing regulatory duties. Firms may use existing compliance mechanisms as a springboard to establish an appropriate compliance framework. However, given the broader nature and the heightened requirements under the Consumer Duty, compliance with existing rules may not be sufficient in all circumstances to prove compliance with all aspects of the new Consumer Duty.12

The FCA has confirmed that the Consumer Duty applies to all businesses that have a material influence over, or determine, retail consumer outcomes. For example, it applies to businesses that can influence material aspects of, or determine:

- how retail products or services are designed or operate, including their price and value;

- how retail products or services are distributed;

- communications issued to retail consumers; or

- consumer support provided to retail consumers.13

Whether a material influence exists depends on the actual circumstances. For example, a material influence would not include a firm whose role is limited to:

- operating within a mandate that is determined by another firm in the chain;

- supporting the work of another firm in the chain through the provision of factual information; or

- providing IT systems.14

The extent of a firm’s obligations under the Consumer Duty will depend on its role and the reach of its influence over retail consumer outcomes, even where the end consumers in the distribution chain is not a direct client of the business concerned.15

The Outcomes

The Four Outcomes represent the key elements of the firm-customer relationship, and build on the Consumer Principle and the cross-cutting rules:

(1) Products and Services

To be able to deliver good consumer outcomes, all products and services for consumers are expected to be fit for purpose, i.e. designed to meet the needs, characteristics and objectives of a target group of consumers and distributed in an appropriate manner. It should be noted that a firm can be both a manufacturer and a distributor.

The FCA is proposing to impose different obligations for firms, depending on their role in the distribution chain, as tabulated below.

| Role |

Who is captured |

Non-exhaustive list of obligations |

| Manufacturers |

A firm which:

- creates, develops, designs, issues, manages, operates, carries out, or (for insurance or credit purposes only) underwrites a product or service; or

- in relation to a closed product or an existing product:

- created, developed, designed or issued the product; or

- manages, operates, carries out, or (for insurance or credit purposes only) underwrites the product.

Intermediaries may also be considered as co-manufacturers, especially where they ‘set the parameters of a product and commission other firms to build it’.16 |

The key obligations include the requirements to:

- identify a target market of consumers for a product or service, having regard to their needs, characteristics and objectives;

- select appropriate distribution channels for the target market;

- provide distributors with sufficient information covering the product or service, as well as the target market;

- conduct testing on the product or service to make sure that it aligns to the needs, characteristics and objectives of the target market concerned; and

- conduct regular reviews of the product or service, how it is being distributed, and introduce appropriate mitigation action where there are circumstances which may have an adverse consumer impact.

|

| Distributors |

A firm which offers, sells, recommends, advises on, arranges, deals, proposes or provides a product or service. |

The obligations include:

- developing arrangements for the distribution of every product or service;

- ·obtaining information from manufacturers to allow them to understand the product or service, who the target market is and the relevant distribution strategy;

- conducting regular reviews of the distribution arrangements to ensure they remain appropriate, and take steps to mitigate any identified issues and prevent further harm; and

- for all firms in the distribution chain, sharing sales information with manufacturers.17

|

| |

|

|

(2) Price and fair value

The FCA wants all consumers to receive fair value. In the FCA’s view, value is about more than just price. It wants businesses to assess their products and services in their totality to ensure that the price a customer has paid for a product or service is reasonable compared to the overall benefit the consumer obtains. The FCA makes clear that low prices do not always mean fair value. Importantly, businesses must make an assessment of value when designing products or services and prior to offering them to consumers. They must also ensure that the price represents fair value for a foreseeable period of time and throughout the lifespan of those products or services. Appropriate action must be taken where a firm identifies that a product or service does not provide fair value.

In order to assess whether a product or service provides value, the FCA expects businesses to consider at least the following:

- the nature of the product or service, including any benefits to be provided or may reasonably be expected and their qualities;

- any limitations which form part of the product or service. For instance, any limitations regarding the scope of cover for insurance products; and

- the anticipated total price customers will pay. This includes all applicable fees and charges over the duration of the relationship between customers and firms.

If products and/or services are sold together as part of a package, it is important to ensure that fair value attaches to each component product or service as well as the overall package.

(3) Consumer Understanding

The FCA wants consumers to be provided with the necessary information at an appropriate time, with the information presented in a manner to facilitate their understanding.

Principle 7 requires businesses to communicate information in a way which is clear, fair and not misleading. Building on Principle 7, the Consumer Understanding principle extends the requirement for firms to:

- ensure that communications between businesses and consumers are designed to meet the information needs of consumers, readily able to be understood by consumers within the target audience, and assist consumers to make decisions that are well informed, effective, and timely;

- tailor communications and the communication channels used in light of the specific circumstances, including characteristics of vulnerability held by the consumers who are the intended recipients of the communication and the complexity of the product;

- when interacting directly with a specific customer, where appropriate, tailor communications to meet the information needs of that customer, as well as asking them if they understand what is being communicated and if the customer has any further questions; and

- test, monitor and adapt communications to support understanding and good outcomes for customers.

An important question the FCA is encouraging all businesses to ask themselves in the context of this outcome is ‘whether they are applying the same standards to ensure their communications are delivering good consumer outcomes as they do to ensure their communications help to generate sales and revenue’.18

(4) Consumer Support

The Customer Support rules are the overarching requirements set out by the FCA in terms of the level of support that businesses are expected to provide to consumers for the duration of their relationship with the firm. Firms should provide a level of consumer service enabling consumers to realise the benefits of the purchased products and services and ensure that they feel supported to pursue their financial objectives.

The rules under the Consumer Support outcome and the Consumer Understanding outcome are closely related. In particular, the FCA states that ‘[u]nder the consumer understanding outcome businesses should communicate with customers in a way that equips them to make effective, timely and properly informed decisions. Under the consumer support outcome businesses should enable customers to act on these decisions without facing unreasonable barriers’.19 Businesses should always remind themselves of their obligations under both outcomes in all consumer interactions.

An important question the FCA is encouraging all businesses to ask themselves in the context of this outcome is ‘whether they are applying the same consumer support standards to deliver good consumer outcomes as they do to help generate sales and revenue’.20