Background

The Hydrogen Production Business Model (HPBM) is one of the UK Government’s support schemes for low carbon hydrogen production in the UK, introduced as part of the hydrogen provisions within the recently passed Energy Act 2023 (for the detail of the legislation, you can read our briefing here). The HPBM will provide revenue support to successful eligible projects. The first hydrogen allocation round (HAR1) opened in July 2022 and was restricted to electrolytic hydrogen projects only. It targeted 250 MW of production capacity by way of revenue support under the HPBM, which comprises a bespoke Front End Agreement (setting out the key project parameters) and a standard form Low Carbon Hydrogen Agreement (LCHA). On Thursday 14th December 2023, the UK Government announced 11 successful applicants from the HAR1 process1, totalling 125 MW of production capacity, who will be invited by the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) to finalise negotiations on the terms of support on a bilateral basis.

The UK’s second Hydrogen Allocation Round (HAR2) was opened concurrently with the publication of successful bidders under HAR1. It aims to support up to 875MW of capacity in 2025 (subject to affordability and value for money) and has increased from the 750MW originally slated for offer, to help keep the government on track for hitting its 1GW target by 2030. HAR2 will again be confined to bids from electrolytic projects only, with a shortlist expected by Autumn 2024 and awards made in early 2025.

In addition to these electrolytic hydrogen projects, the LCHA is also the key document underpinning development of blue hydrogen projects where they form part of a “low carbon cluster” in the UK. Awards for revenue support for CCS-enabled hydrogen projects within clusters will be made outside of the HAR process and so for the purposes of this briefing, we will focus on electrolytic projects.

The first draft of the LCHA was published by DESNZ in August 2023 and is now in the late stages of being finalised, with an updated version due to be released imminently. Despite the agreement not being in final form, an understanding of the contractual framework will be necessary for developers seeking support in the upcoming funding rounds. In this briefing, we summarise some of the key considerations for those developing and financing UK hydrogen projects supported by the HPBM, and share insights based on our work to date with one of the successful bidders under HAR1.

Eligibility

To be eligible for funding under the HPBM, producers must produce hydrogen which meets the Low Carbon Hydrogen Standard (LCHS) according to the version in force at the time of entry into the HPBM documentation2 and must sell those volumes to Qualifying Offtakers. The concept of Qualifying Offtakers excludes the sale of hydrogen to “risk taking intermediaries” (in essence, energy traders), exporters and those who purchase volumes for the purpose of blending hydrogen with natural gas for injection into the grid.

LCHS Compliance

The LCHS establishes what constitutes “low carbon hydrogen” at the point of production by stipulating, among other things, the maximum level for greenhouse gas emissions permitted in the hydrogen production process. Currently, the producer must be able to report that each consignment of hydrogen (i) has a GHG emissions intensity of 20gCO2e/MJLHV of produced hydrogen or less, and (ii) has been produced by a hydrogen production facility which satisfies the “Conditions of Standard Compliance” (which are further detailed in the LCHS).

Strict compliance with the LCHS is a pre-requisite for electrolytic projects to receive revenue support under the LCHA. A breach of this requirement will result in the relevant consignment of hydrogen being deemed non-compliant and therefore ineligible for support under the LCHA. The LCHS sets out the methodologies which producers must use to calculate the facility’s final GHG intensity and provides guidance on how to treat emissions resulting from non-production. The LCHS is technology agnostic, as it applies to numerous eligible hydrogen production pathways, including electrolysis, and will therefore be applicable to electrolytic projects as well as those which employ carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies. The LCHS is now in its third iteration, although subject to change over time for future allocation rounds. The LCHA will confirm which version of the LCHS is applicable to the project when establishing whether the hydrogen produced constitutes a “Qualifying Volume”.

LCHA Overview

The LCHA is a long-term contract, entered into between the developer as the Producer and The Low Carbon Contracts Company Ltd (the LCCC) as the LCHA counterparty, for revenue support (covering price and volume risks, within limits) over a fifteen year period. Under the LCHA, price support is set at an agreed price for hydrogen known as the “strike price” (representing the cost of production plus an allowed return). The LCHA is largely based on the standard terms and conditions underpinning the Contract for Difference (CfD) regime in the UK, which many developers and financiers may be familiar with from the CfD’s successful support of the UK renewables sector. Whilst concepts in the LCHA will be familiar to renewable energy developers, the risk allocation in the LCHA is significantly different from that of a normal take-or-pay gas contract conventionally used to underpin the financing of gas projects. Whilst there are many similarities between the CfD and the LCHA, there are some notable differences which participants in the sector need to understand. Below, we set out the key cashflows available under the LCHA, and explore three key commercial takeaways and bankability considerations, focussing on electrolytic projects.

Key Payments Streams

There are three ways in which a producer can benefit from government support under the LCHA, and we explain these below.

1) Difference Amount

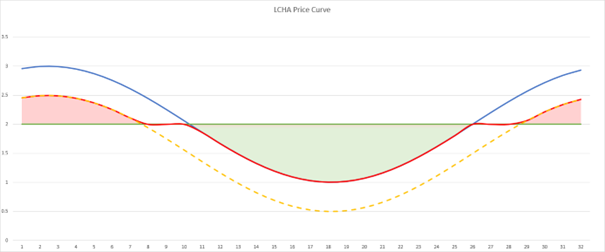

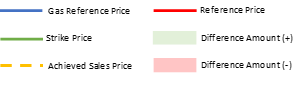

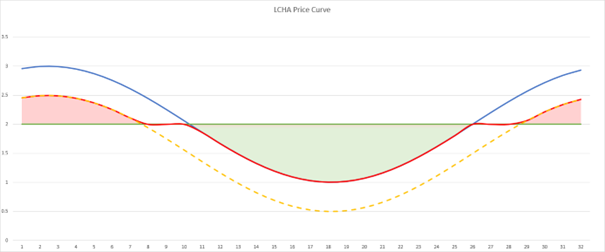

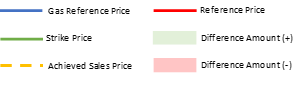

The “Difference Amount” payable follows the cashflow principles under the CfD, whereby the amount payable to or by the producer will be determined by the difference between the Strike Price and the Reference Price. As there is currently no liquid market for hydrogen in the way that there is for electricity in the UK, the Reference Price is set at the higher of (i) the Achieved Sales Price for that period (i.e. the actual price achieved under the relevant offtake agreement) and (ii) the Floor Price (which is in turn set in each period at the lower of (a) the price of natural gas and (b) the Strike Price). Given the issues caused by record-breaking high gas prices in the recent past, it may be surprising to see projects dependant only on electricity as an input once again having their revenues pegged to gas prices, with no allowance made for fluctuating electricity prices. However, this appears to be the model DESNZ is most comfortable with and remains the preferred choice for now.

For clarity, the graph in Figure 1 helps to explain how the pricing works. In essence, the LCCC tops up the producer’s revenues for the difference between the Strike Price and the Gas Reference Price and the Producer is required to pay amounts to the LCCC where the Achieved Sales Price exceeds the Strike Price.

Figure 1

2) Price Discovery Incentive

To incentivise producers to achieve a sales prices above the price of natural gas, an upside-sharing incentive has been included in the LCHA, whereby the producer will receive a portion of the difference between (i) the lower of the Reference Price and the Strike Price and (ii) the Floor Price. The Price Discovery Incentive Ratio has been set at 10%, meaning that only 10% of this additional sales value will be passed on to the producer. This level has generally been considered by industry as a low threshold for incentivising higher pricing strategies with offtakers.

3) Sliding Scale Top-Up Amount

If the total volume of hydrogen sold in a billing period falls below 50% of the forecast reference volume, the producer will receive a top-up amount for each qualifying unit of hydrogen sold. The producer will not be able to rely on this volume support if the reduction in sales is caused by an event which is not demand-related (for example, a facility outage). This mechanism, and the conditions which apply to it, are explored further below.

Key Commercial Considerations

Negotiating a Strike Price

When negotiating a strike price, developers will need to consider carefully which elements of the capital and operating costs should be submitted, as these will be closely scrutinised by DESNZ in order to satisfy the “value for money” requirement. Some of these costs, such as electricity input costs during renewables downtime, will be hard to price due to price volatility generally and the timing of securing a firm offer from the supplier. Other costs may be easier to calculate, but only offer the best value when a project is running at maximum efficiency or after a future intended expansion – for example, the cost of the workforce or for IT security systems. But projects cannot run with half of a person or three quarters of the necessary IT equipment, so may be easier to justify where they represent full utilisation of such worker or equipment. Lastly, producers should consider which costs could reasonably be passed through to offtakers as part of the sale and delivery arrangements, rather than sit within the operating cost calculations.

Price adjustments

Once the strike price has been agreed and documented in the LCHA, there are limited circumstances in which it can be adjusted. For electrolytic projects, the strike price will be adjusted for indexation annually, calculated as at 1 April each calendar year and using CPI for January for the relevant calendar year. Conversely, for CCUS-enabled projects, indexation is linked to the price of natural gas, which acts as a natural hedge against fluctuations in the fuel costs. Consideration will likely need to be given to the pricing mechanics of the underlying power purchase agreements, given that electricity supply will be of particular importance in the context of a green hydrogen project. The capital return component of the Difference Amount is also subject to CPI-linked indexation each year. A qualifying change in law may give rise to increased costs and, in such circumstances, compensation may be payable by the LCCC to the producer. This can be done as an adjustment to the strike price. No adjustment to the strike price will be made solely as a result of an adjustment to the Installed Capacity Estimate of the facility.

Termination Rights

In line with the CfD, the producer does not benefit from any termination rights under the LCHA. There are five key categories of circumstance that give rise to a right for the LCCC to terminate the LCHA. These termination rights typically have short cure periods for the producer to remedy a breach, and it is important that developers understand their obligations under the LCHA ahead of contracting with the LCCC. Although a breach can be remedied, there is no absolute obligation on the LCCC to withdraw a termination notice if one has been issued, and no materiality threshold to protect the producer against a minor administrative error giving rise to a right to terminate. In addition, where the LCCC terminates the LCHA, a termination payment will need to be made by the producer, with interest, within thirty days of termination.

(a) A failure to deliver certain conditions precedent and milestone deliverables by the applicable longstop dates under the LCHA, some of which are deliverable shortly after entering into the LCHA;

(b) A force majeure event occurring and continuing for a period of eighteen months;

(c) A failure to commission 90% of the Installed Capacity Estimate for the facility by the applicable longstop date;

(d) A qualifying change in law occurring which results in construction or production becoming prevented permanently; and

(e) The occurrence of certain other events considered to be “Termination Events” under the LCHA, such as producer insolvency, failure to comply with the metering requirements and non-payment.

See below for further detail on the termination events triggered by breaches of the annual and overall sales caps.

Key Bankability Considerations

Offtaker requirements

Hydrogen is not physically transferred under the LCHA (i.e. the LCHA Counterparty does not act as a buyer of low carbon hydrogen) and the producer is required to sell its hydrogen to “Qualified Offtakers” through bilateral offtake agreements. This contrasts with European support schemes such as H2Global and the Hydrogen Bank. As the hydrogen market is in its infancy, and the HPBM is designed only to support the domestic market within the UK, one of the key challenges will be securing long-term offtake contracts that align with the 15 year term of the LCHA. This challenge is compounded by extensive requirements in the LCHA related to the offtaker(s), including periodic reporting obligations, the disclosure of a copy of any offtake contracts to the LCCC and the requirement that certain offtaker compliance requirements are passed through to offtakers under the offtake agreement.

Risk Taking Intermediaries (i.e. where the legal and beneficial title to the hydrogen is transferred by the producer to an entity which then contracts with another entity to further transfer the legal and beneficial title in the same volumes of hydrogen, such as traders, storage providers, etc.) are considered Non-Qualifying Offtakers under the LCHA. Any hydrogen sold to such entities will be ineligible for support under the LCHA. This is driven by the overarching framework of traceability in the LCHA. This approach will limit the pool of potential offtakers and, beyond own consumption and shareholder offtakers, will require the producer to have a direct relationship with the end-user offtaker. However, given the allocation of funding is part of a wider drive to hit the binding decarbonisation targets for the UK in the Climate Change Act 2008, and also given that decarbonisation of hard-to-abate sectors is considered the ideal use case for hydrogen, it is perhaps unsurprising that these strict conditions have been included.

Volume Risk

Volume support is made available to the producer under the LCHA such that the producer will receive a top-up amount for each qualifying unit of hydrogen sold (the Sliding Scale Top Up Amount) where total invoiced volumes are reduced by events or circumstances other than as a result of, among other things, the producer’s breach or default under the LCHA or offtake agreement or its negligence, operation of the facility in a manner designed to maximise claims for the Sliding Scale Top Up Amount, or events or circumstances where the hydrogen production plant is unavailable, curtailed or derated (including full unavailability to produce hydrogen). The Sliding Scale Top Up Amount is only made available if the volumes sold fall below 50% of the reference volume (i.e. the volume expected to be invoiced) in a billing period, but do not fall to zero. Both of these thresholds have been highlighted by industry as problematic. It is a significant limitation to the support framework as a whole that a reduction in demand by, for example, 40%, could have a meaningful economic impact on a project’s viability, yet is not recognised as sufficiently serious to warrant intervention. This would seem to materially restrict the debt sizing capacity of projects benefiting from an LCHA. Volume risk and its treatment under the LCHA should be considered by developers when structuring the project’s offtake strategy – for example, a diversification of offtakers could help to minimise the risk of no volume support being accessible under the LCHA.

One way sellers of gas traditionally mitigate demand risk is via “take or pay” obligations. Under the LCHA, volumes sold on a take or pay basis but not in fact delivered are not included within the calculation of “total invoiced amounts” and as such, a producer may decide it is better to protect against demand risk outside of the government support offered, so that offtakers continue to pay regardless of accepting the hydrogen, and there is no need to wait for the 50% drop in demand until compensation kicks in.

Sales Cap

There are two notable sales caps which apply to the producer under the LCHA:

(a) A cap on the overall volumes which will be supported over the life of the LCHA (LCHA Sales Cap); and

(b) A cap on the volumes which can invoiced in any fiscal year (Permitted Annual Sales Cap).

According to the LCHA Sales Cap, the producer will be subject to an overall cap on the volume of hydrogen that can receive support under the LCHA, representing the hydrogen production facility’s forecast total volumes during the 15 year term of the LCHA. Whilst non-qualifying volumes produced and sold by the facility to not receive support under the LCHA, they will count towards the LCHA Sales Cap. If the volume of hydrogen produced and sold is above the LCHA Sales Cap then the LCHA will expire automatically. It will be important to understand how forecast volumes produced are modelled across the term of the LCHA, to ensure that developers and financiers are comfortable that these caps will not be breached and inadvertently trigger the early expiry of the LCHA. From a bankability perspective, financiers may require the ability to monitor the levels of hydrogen produced and the inclusion of cash sweeps in the event that such obligations were breached.

The Permitted Annual Sales Cap is set at 125% of the Reference Volume adjusted for the number of days in the year rather than a billing period. Any volumes invoiced in a fiscal year above the Permitted Annual Sales Cap will be considered non-qualifying excess volumes which (i) will not receive support under the LCHA but (ii) will count towards the overall LCHA Sales Cap. If the Permitted Annual Sales Cap is breached more than twice, a termination right will arise in favour of the LCCC. Unless sales are forecast to be relatively steady each year, the 25% buffer applied to each fiscal year may be insufficient and this should be considered when modelling the project.

LCHS Certification

Certification schemes are a key tool enabling producers of low carbon hydrogen to evidence compliance of projects with the relevant low carbon hydrogen standard. The UK Government recently confirmed its commitment to delivering a low carbon hydrogen certification scheme by 2025, which would independently verify satisfaction of the LCHS requirements. This scheme is initially anticipated to be voluntary and, whilst it will have a domestic focus, the government has highlighted its aim for international alignment once hydrogen is traded overseas. This process will help demonstrate compliance with the HPBM and will provide certainty to offtakers that the hydrogen purchased meets the requisite standard to consider it “low carbon”. From a financing perspective, this certification scheme may also be a useful tool in the context of the reporting obligations of any lenders who may make green / sustainability-linked loans available to such projects.