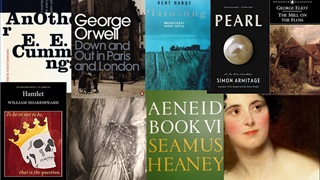

Bookshelf

The place to build your library

Farmida Bi in London on the twelve books that track her life

Charlotte Bronte

I love all the Brontes (much more so than the polished, rather distant Jane Austen) but Jane Eyre is my absolute favourite. I love Jane. She has a lonely and harsh childhood but develops a deep sense of what is right, and her cry of “Do you think because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! I have as much soul as you—and full as much heart” for me is a declaration of universal humanity that ranks right up there with Shylock’s “If you prick us, do we not bleed”! This romantic, emotional and moral novel appeals to bookish children as well as adults. I must have been eleven or twelve when I first read it and it did help to form me as an adult.

(The 1980s BBC production of Jane Eyre with Timothy Dalton as Rochester is brilliant.)

Louise May Alcott

This was one of my favourite books when I was growing up, as I suspect it is for many girls who love reading and harbour a secret desire to write. It has been repeatedly filmed and so the story is familiar to many people: four teenage sisters living with their mother in Concord, Massachusetts and navigating their way to adulthood while their father is away in the American civil war. A boy, Laurie, appears next door and becomes a good friend of the tomboyish Jo as well as that of her sisters. The four sisters represent different models of womanhood from the mid nineteenth century America: Meg, who is sensible and practical; Jo, who wants to be a writer and longs for the freedom that boys have (and to travel to Europe); Beth, who is saintly and self-sacrificing; and Amy, who is vain and silly and wants to marry a rich man. The book has the most annoying ending of any book I have ever read, but I love Jo and her desire to be independent and to support her family through her writing (and the sale of her ‘one beauty’).

Noel Streatfeild

I never did ballet as a child but this book was a dear favourite, although it may be a bit unfashionable now. It is the story of the Fossils, three girls who mysteriously arrive as babies at the house on the Cromwell Road occupied by the adult Sylvia and her nanny, called Nana. They are sent by Great Uncle Matthew, who is away on a long fossil hunting trip and for some reason keeps finding babies... Money eventually runs out for Sylvia and in addition to taking in boarders she and Nana send the girls to a ballet school so they can contribute to the family budget and learn a skill. The girls are very different. Pauline is beautiful and a talented actress and Posy, the youngest, is a prodigy ballerina. Petrova, the middle girl, hates ballet, can’t dance at all and is only interested in engines and cars and aeroplanes. The book charts the girls from babyhood until they grow up and start their careers. I loved the fact that they were so different but formed a family and chose their own name—Fossil—because they were sent to the house instead of the fossils that GUM normally sent back from his trips, and at each birthday they make a solemn and secret vow to make the Fossil name great!

Ronald Cohen

Reading Impact over the summer of 2020 has radically changed my view of the future of capitalism. I believe now that ESG (environmental, social and corporate governance) will become a part of mainstream capitalism in the way that maximising shareholder profit has been in the past. Sir Ronald Cohen was the co-founder of Apax Partners, a global equity firm, and has focused on social investment for the last two decades. He explains what is happening in the world of ESG finance now, how widespread the approach is and how impact can be measured. I think it is vital reading for all of us and helps to give us hope that the markets can be used to effect positive change.

Paul Collier

This book is as depressing as Impact is uplifting and, for me, the two are connected. The economist Paul Collier says that, although nearly five billion of the world’s people are beginning to climb out of poverty and to benefit from globalization, there is a ‘bottom billion’ of the world’s poor who are falling farther behind. Collier identifies and explains the four traps that prevent the world’s billion poorest people from growing and receiving the benefits of globalization: civil war; the discovery and export of natural resources in otherwise unstable economies; being landlocked and therefore unable to participate in the global economy without great cost; and, finally, ineffective governance. Collier identifies the problems and I am sure that, with focus and impactful financing, we can overcome them so that in thirty years’ time there is no ‘bottom billion’.

Doris Kearns Goodwin

This is a highly readable account of Lincoln’s political genius (and his basic decency—a much underrated and rare quality in politicians) and provides a great political summary of the US Civil War as Lincoln, the one-term Congressman and prairie lawyer, rises from obscurity to beat three gifted rivals—William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase and Edward Bates—to become President. He has to deal with the poisoned chalice of slavery, including the resultant secession by the South and Civil War. Lincoln had the courage to bring his talented former rivals into the heart of his administration as saving the nation became more important than the ambitions of any one man. Goodwin really brings Lincoln, Seward, Chase and Bates alive as they try to avoid war and, when it becomes inevitable, to ensure that victory goes to the North. As we see modern-day politicians struggling with the huge issues of the day, the morality and strength shown by Lincoln and his former rivals is a reminder that it doesn’t always have to be about taking the low road to personal advantage.

David Olusoga

David Olusoga writes about the presence of black people in Britain from Roman times to the modern day, as the numbers and their attitude to them changed through Tudor, Georgian and post-War Britain. I was amazed to find that black British history did not begin with the arrival of MV Windrush in 1946 and Romans were not racists. This is a history that we should all know about and we have to ask ourselves why we don’t. Was it suppressed from the school curriculum or just forgotten? Olusoga brings to life the black Britons who navigated their way through life as Tudor trumpeters or Georgian writers and those who supported them, like the abolitionist Granville Sharpe who used the English courts to help escaping slaves. He also explains the consequences of slavery and its abolition on the British economy.

(It is also worth reading William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy about the East India Company and its importance to the growth of the British Empire. I have found both of these books to be vital reading to fill in the gaps in my understanding of British history.)

Leo Tolstoy

I read Anna Karenina as a teenager and re-read it about once each decade. I love Tolstoy’s humanity and sympathy for all his characters as well as his dissection of society and the big political issues, but the reason I read Anna Karenina every ten years or so is because, as I have become older, I recognize more truths about human relationships and I’m more sympathetic to all the characters that Tolstoy creates and the situations they find themselves in. Despite the quite simple plot of ‘bored young wife has her head turned by a dashing officer and abandons her dull husband and young son and in turn becomes a social embarrassment for her lover’, I learn each time that the world is less black and white and that every person suffers in their own way… So much kinder than Madame Bovary.

Sigrid Undset

I had not imagined that a Norwegian novel set in the fourteenth century would be an exciting page-turner but that was before I read Kristin Lavransdatter, by the Nobel laureate Sigrid Undset (translated by Tiina Nunnally) and found myself visiting Trondheim cathedral, where a significant event in the plot happens!! The novel is about a strong-willed young woman who meets and marries the charming and impetuous Erlend Nikulaussøn against the wishes of her family, but instead of a ‘happy ever after’ the book describes her whole life, including her marriage to Erlend, their tumultuous life together raising seven sons as Erlend tries to strengthen his political influence, their separation, the role of faith and the plague in their lives, as well as the settlement of Greenland (where two of their sons go).

Daniyal Mueenuddin

There are a number of excellent Pakistani writers at the moment including Mohsin Hamid (e.g. The Reluctant Fundamentalist) and Kamila Shamsie (e.g. Burnt Shadows) but the reason I chose Daniyal Mueenuddin’s In Other Rooms, Other Wonders is that its eight short stories describe the lives of ordinary people living in the countryside (who have never seemed worthy of notice by the sophisticated literati in Karachi or Lahore) as well as the lives of their feudal overlords. I was so excited when I first read this book that I had to buy copies for lots of people I know with the message ‘This is what Pakistan is actually like’! It’s not always a pretty sight, but I am so glad that it has been described, in beautiful, spare prose.

Atul Gawande

Being Mortal is a book we all need to read as we live in a world where too often we deny the existence of death and resist it at all costs, even in the midst of a pandemic. ‘More life’ is our (and the medical profession’s) default assumption, but the surgeon and writer Atul Gawande focuses on the decisions that have to be made at the end of life, when our choices are reduced, and asks us to consider whether a shorter, more meaningful life, where we are able to say goodbye and focus on the people and things we love, might not be preferable. The book deals with a very difficult subject through the stories of family, friends and patients and forced me to think about choices I hope I will never have to make but am glad to have had an opportunity to consider.

Nora Ephron

Nora Ephron is funny about everything, including aging, and I have read everything she has written. This is a book of short articles about women who are getting older and dealing with the tribulations of maintenance, menopause, empty nests, and life itself, interspersed with recipes and her very New York take on life. It’s a great book to dip into for a quick smile of recognition. I wish she was still around to mock all the craziness there is in the world now.

RE: Issue 18 (2020). Farmida Bi, CBE, is the chair of Norton Rose Fulbright’s EMEA practice.

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025