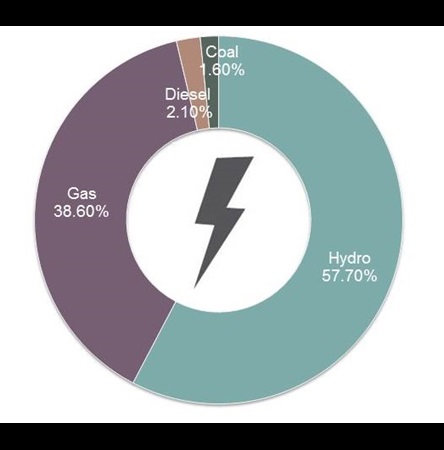

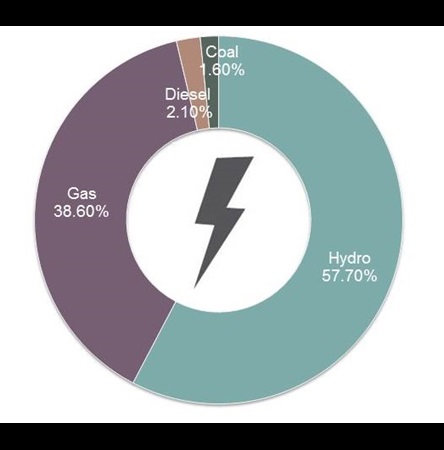

Current energy mix for power generation

Renewable energy and electrification targets

The Myanmar Energy Master Plan, published in January 2016, makes projections of the long-term energy demand and fuel supply mix up to the year 2030. The plan anticipates that the share of solar and wind in the total energy mix by 2030 will be around 1.2 per cent. More recently, the Ministry of Electricity and Energy has introduced ambitious renewable energy targets that aim to increase the share of renewables in electricity production to 8 per cent by 2021 and to 12 per cent by 2025.

Myanmar’s National Electrification Programme 2015 (NEP) aims to connect all Myanmar households to a supply of electricity by 2030. As at 2017, Myanmar’s electrification rate was 39 per cent. The NEP targets an electrification rate of 50 per cent by 2020, 75 per cent by 2025 and 100 per cent by 2030.

The NEP comprises a grid extension programme and an off-grid programme. In the short- to medium-term, off-grid solar home systems and mini-grid solar / solar/hybrid projects aim to connect households in remote locations where the costs of grid access are prohibitively expensive.

Existing renewable projects

Solar

The Asian Development Bank estimates Myanmar’s potential solar resource at 27 GW. To date, very little of this potential has been realised.

Currently, Myanmar only has one utility-scale solar power project that has reached full commercial operation, the 170 MW Minbu solar project located in Minbu Township, Magwe Region.

Other than non-utility scale rooftop solar projects, there is a general paucity of developed solar projects in the pipeline, however a notable exception is the 200 MW Meiktila Township solar project. Several additional projects are in various stages of discussion and documentation and, if realised, could contribute an additional 1.3 GW of solar capacity.

With funding from the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and other international development finance organisations, off-grid household solar projects and mini-grid solar projects have been a key driver of electrification in Myanmar. To date, they have mostly been utilised for households, villages, schools and hospitals.

Wind

Myanmar does not have any wind power projects generating electricity at present. In March 2016, the Ministry of Electricity and Energy (MOEE) signed a memorandum of understanding for the private construction of a 30 MW wind turbine project subject to the successful conclusion of feasibility studies.

Similarly, in December 2018, the MOEE signed an agreement with a developer to carry out feasibility studies for several wind power projects. The results of the feasibility studies have not been announced.

Large Hydro

Large scale hydroelectric projects are considered state-controlled assets, but may involve private sector participation. In the pipeline are a number of private investor driven hydroelectric projects, the largest being the proposed 670 MW Shweli 3 hydropower project in Shan State. These projects are still in the project document negotiation phase.

Small hydro

Myanmar has at least 30 small hydropower projects producing less than 10 MW per project. There are potentially several more small hydroelectric projects, but the published statistics are infrequently updated.

Electricity industry structure

The Ministry of Electricity and Energy (MOEE) controls the electricity industry. The MOEE consolidates the former Ministry of Energy and the Ministry of Electric Power, which existed prior to March 2016. The MOEE is divided internally into two branches, the “Electric Power” branch and the “Energy” branch.

Private sector participation is permitted in the generation of electricity, whereas the sale and distribution of electricity is strictly limited to government entities.

We set out below a description of the departments, enterprises and corporations under the MOEE’s purview relating to the electricity branch

Departments

- Department of Electric Power Planning (DEPP) - responsible for the planning and coordination of all matters relating to electric power in Myanmar.

- Department of Power Transmission and System Control (DPTSC) - develops, regulates, and implements the transmission network in the form of the Myanmar National Grid System.

- Department of Hydropower Implementation (DHPI) - responsible for planning hydropower projects to be implemented either by the Government of Myanmar or the private sector.

State-owned enterprises

- Electric Power Generation Enterprise (EPGE) (formerly the Myanmar Electric Power Enterprise) - operates government electricity generation assets and plans the future generation of electricity in conjunction with the DEPP. EPGE also buys electricity from private producers and sells the electricity to distributors (ESE, Yangon Electricity Supply Corporation and Mandalay Electricity Supply Corporation).

- Hydro Generation Enterprise (HPGE) - is controlled by the Department of Hydropower Planning and the Department of Hydropower Implementation. HPGE is responsible for all hydroelectric projects and is the offtaker for electricity produced by hydroelectric independent power producers (IPPs). HPGE also operates and maintains all large scale public sector hydroelectric facilities.

State-owned corporations:

- Yangon Electricity Supply Corporation (YESC) - responsible for the supply of electricity to consumers in Yangon.

- Mandalay Electricity Supply Corporation (MESC) - responsible for the supply of electricity to consumers in Mandalay.

The Electricity Law (the 2014 Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Law No.44) was enacted in 2014 (Electricity Law). The Electricity Law creates

the Electricity Regulatory Commission (ERC). Amongst other things, the ERC will be responsible for creating policies and standards, setting tariffs, reviewing the electricity sector and advising MOEE. At the date of publication of this renewable snapshot, the ERC is yet to be formed.

There is no specific legal framework for renewable energy in Myanmar. The development of medium and small power projects (of capacity less than 30 MW), that are not connected to the grid, requires the permission of state and regional governments.

Other key regulatory institutions are the Myanmar Investment Commission, the Directorate of Investment and Company Administration and the Central Bank of Myanmar.

Project procurement

Myanmar does not have specific laws related to the procurement of power projects. According to President’s Office Directive 1/2017 (Tender Directive) all projects in excess of MMK 10 million must be tendered.

In practice, almost all projects in Myanmar thus far have been the conclusion of government-to-government negotiations or originated in the form of unsolicited proposals by private companies. We expect this to continue going forward.

In November 2018, the President’s Office promulgated Notification 2/2018 (Project Bank Notification), which establishes a central database of key projects which the government wishes to prioritise as part of the Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan 2018-2030. The intention is to enhance transparency and attract investment to those particular projects.

At the time of writing, the Project Bank website is not yet live. We understand that the Project Bank will include at least one solar project that seeks to use unutilised government land and which is to be jointly implemented by private investors and the Ministry of Industry.

Incentives

Myanmar currently does not have any incentive schemes for renewable energy projects specifically.

However, foreign investors are typically entitled to a package of tax incentives under Myanmar’s investment law once they have obtained a Myanmar Investment Commission permit. Import tax waivers for products made in ASEAN countries and China may also apply.

Tariff

Tariffs for renewable and non-renewable electricity projects in Myanmar are negotiated on a project-by-project basis. There is no prescribed feed-in tariff, each project is considered on a case-by-case basis.

A longstanding issue and cause of delay for project implementation was the low electricity tariffs charged by the relevant electricity supply corporations (e.g. YESC) to end-consumers. This led to a highly subsidised market which effectively inhibited EPGE’s ability to conclude power purchase agreements (PPAs) with market-based tariffs. To entice foreign investors, power purchase prices under IPP PPAs could not reflect actual consumer retail tariff rates collected by the relevant electricity supply corporations. Another complexity is that the retail rates charged to end-consumers are based in Myanmar kyat, although PPAs with international sponsors have been concluded in United States dollars. To avoid accepting the currency exchange risk, EPGE’s preference is to pay in Myanmar kyat, however this is not generally acceptable to international lenders. Therefore domestic hydropower sponsors have accepted PPAs which include Myanmar kyat payments, due to the limited need for international finance.

In July 2019, the Government of Myanmar has raised the electricity tariffs charged to end-consumers in an effort to accelerate and strengthen the pipeline of power projects by reducing the necessity to subsidize the market.

Rooftop solar and net metering

Myanmar does not have any regulations aimed specifically at the solar rooftop business. Myanmar does not operate a net metering scheme.

Foreign ownership restrictions

Foreign investors can own up to 100 per cent of the equity in renewable projects.

Restrictions on equity transfer

There are no restrictions on equity transfer in Myanmar law, however such restrictions are usually stipulated in the power purchase agreement or concession agreement. Although it varies from project–to–project, EPGE has previously required the key equity investor to maintain a majority shareholding until the first anniversary of the commercial operation date and thereafter to maintain at least 25 per cent of the shares in the project company until the fifth anniversary of the commercial operation date.

Prior lending

The first IPP to be financed on a project finance basis was the Myingyan 225 MW gas-fired power project, which achieved financial close in late 2017. The sponsors of that project are Sembcorp Utilities Pte Ltd and MMID Utilities Pte Ltd. The lenders included International Finance Corporation, Asian Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Clifford Capital, DBS Bank, DZ Bank and Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation along with cover from the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency..

With the exception of the Myingyan project, there has been limited lending from international banks to date, in part given bankability challenges in relation to the power purchase agreements executed for other projects.

Power purchase agreements (PPAs)

The timing and process for execution of the PPA varies from project to project. In many of the prior projects, the PPA was negotiated only after the prior execution of a memorandum of understanding, followed by a memorandum of agreement. In some projects, the PPA may be accompanied by other government facing project agreements such as a build, operate, transfer (BOT) agreement or a concession agreement.

Traditionally, Myanmar has not used a standard form PPA. PPAs signed to date have been negotiated on a project-by-project basis. Existing PPAs vary in sophistication, with some more comprehensive than others.

The PPA for the Myingyan project, which was executed in 2016, was drafted with the assistance of International Finance Corporation and other international transaction advisers to the Myanmar Electric Power Enterprise (now EPGE). The PPA was comprehensive and consistent with the risk allocation generally expected in emerging markets.

The Myingyan PPA was expected to form a precedent for future gas-fired projects. However, in practice, this agreement has been substantially amended for subsequent projects.

Recently, Myanmar has developed a model form of PPA and concession agreement for use in hydroelectric projects. We understand that this model form has similarities to the form of PPA used for the Myingyan project.

There are no other model renewable PPAs in Myanmar at present.

Direct PPAs which are not synchronously interconnected to the national grid have been negotiated and entered for private offtake.

PPA term

The term of the PPA is negotiable on a project-by-project basis. The term of prior PPAs vary greatly, but is generally between 20 to 30 years.

Transmission lines

DEPTSC is the sole-owner of transmission lines in Myanmar. Customarily, a project sponsor constructs the transmission lines through a BTO or BOT scheme.

Deemed commissioning

This has been agreed in the past, but it varies on a project-by-project basis.

Deemed generation

In our experience, the treatment of deemed generation varies and the drafting can be unclear. Like the issue of deemed commissioning, this varies on a project by project basis. In our experience, EPGE is reluctant to agree comprehensive compensation for curtailment.

Take or pay

On limited occasions, PPAs for previous conventional power projects have included take-or-pay payments, which took the form of a fixed capacity payment and a variable energy payment, together with deductions for excessive outages and derating. However, we do not believe these structures will be preferred by MOEE in the future.

More commonly, PPAs specify a variable energy payment with a true-up for the minimum guaranteed output and the minimum guaranteed offtake. The penalties for under-performance vary by season.

Change in law

PPAs in recent years have offered protection for increases in capital and operating costs arising from a change in law. A change in law resulting in a reduction in revenue is less commonly addressed. The treatment of change in tax varies from PPA to PPA. Some PPAs include a change in tax clause. Others pass-through certain taxes.

Termination payments

Compensation on termination is determined on a project-by-project basis. Recent PPAs have included detailed termination payment provisions consistent with regional precedent. Lenders would be entitled to recover the value of the debt in all termination scenarios where EPGE opts to take the plant. Similar to other PPAs in the region, EPGE is not obliged to take the plant and pay compensation if the PPA terminates because of project company default. Sponsors are generally entitled to recover their equity upon EPGE default or political force majeure, together with a portion of their foregone return on equity.

Dispute resolution

Foreign arbitration is permitted, with UNCITRAL terms generally preferred by the government. Typically, the method of dispute resolution is determined on a project-by-project basis. International arbitration awards are generally deemed enforceable under the Arbitration Law of 2016, which implements the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, which Myanmar acceded to in 2013.

Offtaker credit support

No sovereign guarantees have been issued in Myanmar. However, the Myingyan project benefited from a build-operate-transfer agreement with MOEE, which was effectively a guarantee of EPGE’s obligations under the PPA.

The recent Project Bank Notification has stipulated that sovereign guarantees and other forms of government support, such as viability gap funding, will be available to projects in the event that they have been tendered. We expect sovereign guarantees to be issued for large critical infrastructure projects in the future, although specific criteria have not yet been established.

Other significant project development issues

Key challenges

- Lack of feed in tariff scheme

- Lack of transparency in the permitting process

- Delays with land acquisition and conversion for project use

- Concerns regard the bankability of the PPA

- Uncertain national grid performance

Audray Souche

Partner; Co-Head of Regional Energy, Mining and Infrastructure Practice Group

audray.souche @dfdl.com

William Greenlee

Partner, Managing Director Myanmar

william.greenlee@dfdl.com

Dave Seibert

Senior Legal Adviser; Deputy Head of Regional Energy, Mining and Infrastructure Practice Group

dave.seibert@dfdl.com